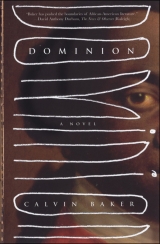

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

The magistrate took Magnus’s old forged papers and embossed them with the great seal of the House of Burgesses. Magnus felt a heavy stone lifted up from him when he saw the official seal of the colony on his freedom. After that, according to all accounts, he was at ease as he had never been before. Not only because he was finally free as other men – he had been that in fact for a long time already and, no matter the outcome of his trial, knew he was not going to be returned to his previous condition – but because he knew the law now stood solidly behind him. He was altogether different after that in the way he encountered and moved through the world. Immeasurably so.

The roads around Berkeley had grown chaotic with activity from the universe outside its boundaries, though, and things did not turn out so fortunately for everyone that year. On the last Sunday in September, Bastian Johnson went out to Turner’s Creek with Caleum and Julius, whose Sabbaths were of his own employ, to fish for walleyes and cat-fish. Of the three, Bastian was most successful that particular day and was overweaning in his pride of the fact.

After they hauled in their catch, which included several speckled rainbow trout as well, the boys built a fire and cleaned some of the fish, then roasted them over the embers. As they ate and relived the adventure of how the fish came to be in their fire, all praising Bastian’s skill, he himself ladled out fishing advice. “Walleyes don’t like no bait too fast. You need patience if you gone catch em. Now, trout is the opposite.” The anglers all reclined on the bluff above to the pool and debated the merits of various bait and techniques for the different fish, such as is common among trawlers and fisherfolk everywhere, regardless of age, language, or particular liking for fish.

As it grew late, Julius, tiring of Bastian, asked whether either of them had heard the tale of Witch Mary from Canary. When they told him they had not, he gave the others the story of how there lived a well-known witch on the African coast who, many years previous, had lost a son of sixteen. “Once a month, every month, she get on her broom and fly over the whole wide world looking for her boy. If she can’t find him, then she snatch another black boy of about his age and take him back with her. They say her son used to brag on hisself and so she always go for a loud talker. Say she keep her victim for about three weeks, but once she start to remember what her son looked like, she kill the one she brought back. They say the last thing he hear before she get him, and right before she kill, is three real loud knocks.”

They were all quiet in the purplish evening light as he told the story, and when he finished all said he had made it up. “That’s just another fish tale,” Bastian cried, waving him off. As they stamped out the fire, though, Julius told them to be quiet and listen. Sure enough, they could hear a sound in the trees like a hammer banging against the bark. When they heard it a second time they began to move closer to each other, uncertain what to do.

“We better go see what it is,” Julius said.

“I don’t think we ought to mess with whatever it is,” Bastian warned, not wanting to venture any deeper into the woods. “It’s getting late out here.”

Finally Julius and Caleum convinced him he was only being scary, and the three set out into the nearby forest. “Keep quiet, though,” Julius whispered, “Cause, if it is Mary, they say she always go for noisiness.”

As they walked on a small path in the direction from which the sound had emanated, they heard it again, then a third time in rapid succession. After the last there was a loud scream right afterward, as Caleum and Bastian both jumped back, startled. As they stood there afright, Julius began to laugh at them. He then pulled his hand through the air in a wide arc, after which there was a loud knock. He moved his hand again and laughed as Bastian and Caleum drew close enough to him to see he was holding a length of fishing twine. At the other end he had affixed a branch, which he could pull through a contraption he had rigged and knock it against a tree. He pulled it once more and laughed at them.

Finally, they laughed at the joke as well, as the three friends parted for the week, each taking with him some of the leftover fish. “Y’all be careful of Mary from Canary on the way home,” Julius called good-naturedly, as he went off to feed his master and mistress.

On his way back to Stonehouses, Caleum was in good spirits, thinking Julius very clever and Bastian in need of the lesson. Indeed, Bastian himself was in a fine mood and did not hold it against his friends for showing him up after he had bragged so much on himself. Still, he remained on edge from his earlier fright as he moved through the forests, and even the slightest sounds made him flinch. Even though he had walked through the woods around Berkeley his entire life, he was glad to be out of them when he reached the main road and breathed altogether easier. When he saw a coach coming down the lane he relaxed completely, no longer being alone on the evening road.

When the coach was even with him it slowed down, and he moved out of the way to allow it to pass. The wagon proceeded on a few paces, then came to a stop. Bastian continued walking in the gulch of weeds on the roadside, wondering briefly what had caused the wagon to stop but being otherwise unconcerned.

Once he was spotted, a man he didn’t know called down to him to ask what he was doing out at that hour. “I’m just comin’ in from Turner’s Creek, sir,” he answered.

“Looks like you had some luck,” the man called back.

“Ah, just a little,” Bastian returned.

“Say, can you tell me how to get to the wheelwright’s place? I think I bent a spoke back there,” the man said.

“You just keep headed straight around that bend,” Bastian answered. “Ain’t but two roads through town.”

“Why don’t you hop up?” the man said. “You might as well ride as walk.”

Bastian thought it odd that a strange white man should offer him a ride and declined, not knowing what sort of fellow he might be and not wanting to fall into the wrong hands.

“All the same,” the man replied, flicking lightly at his reins, until his horses started to gallop. The wagon went on until it disappeared around the bend ahead, and Bastian gained the main road again and continued on, already planning the week before him.

When he reached the bend, though, he found the wagon stopped and the man inside waiting for him with his pistol drawn. “Here, put these on,” the man commanded, throwing him a pair of iron bracelets.

“No, sir,” Bastian said. “My people expecting me.”

“Well, I don’t imagine they’ll be seeing you this evening,” the man told him, busting the side of his head with the pistol butt. Bastian blacked out and fell to the ground.

He woke up in the back of the wagon and, it seemed, as far from Berkeley as he had ever been his entire life. He could not tell by looking out of the tarp where they were, or even whether Berkeley was north, south, east, or west of his position. Through the top of the wagon he could see the sky, and it looked to him the same as the one he was used to, but he knew it was not. The only other thing he knew for certain was that it was deep into the nighttime and he was unlikely to make it home that evening.

Nor had he any sense of bearing until the next afternoon, when they stopped for lunch. The man, whose name he had not yet learned, came into the back of the wagon and gave him a tin plate of hominy that had a tiny piece of hog’s fat in it. “It won’t be so bad,” the man said. “You’ll see, one master is just like any other.” Bastian did not say anything in acknowledgment of this statement, and the man picked up a round stick, which was leaned against a barrel in the wagon, and slammed it into the soles of his feet, so that his knees buckled and he nearly lost the plate from his lap. “You answer when I say something to you,” he said.

After he left, the wagon set off again, and, late that night came into a town. As it moved through the streets Bastian felt a great heart’s sickness when he began to recognize where he was. They were in Bertie County, in Knowleston, which is where he and his family had lived before settling in Berkeley.

When they stopped at the other end of the town it was fully night, and his kidnapper left him in the wagon as he went to negotiate terms in the rooming house. When he came back, he led Bastian into a barn with the horses and tied him to a railing, first making sure he had a blanket and straw for a pallet. “Wouldn’t do for you to catch cold,” the man said, before leaving.

About an hour after he was fastened to the rail, a boy of twelve or so came out with a plate of scraps for him to eat. As he refused the plate, Bastian asked the boy whether he knew Goodwin Johnson’s place.

The boy said he did, and that it was about five miles from where they were.

“That’s my uncle. You got to go tell him what happened to me,” Bastian said, recounting his sad adventure.

The boy was terrified when he heard it but promised he would figure out a way to get word out to Goodwin’s place.

Bastian Johnson did not sleep through that night but lay awake in the foul stench of horse sweat and urine, stirring at the first sound as he awaited rescue. The barn door did not open again until morning, and, when it did, it was Harris, his kidnapper, who entered.

“Wake up,” the man barked. “It’ll never do to be a lazy slave.”

Bastian sat up as commanded, and Harris handed him a bar of soap and a pair of trousers. “You clean up and put these on,” he instructed.

“I can’t take you to market like this. Make sure you wash the mess from your face too. The market subtracts for every defect.”

When he saw the bewildered look on Bastian’s face, he sat down next to him on an overturned pail. “You and me going to the Exchange here today, and I need you to be at your best. If you act up, though, I will kill you. I would rather make no profit than get cheated out of fair value. Now, what do you suppose you might be worth?”

Bastian stayed silent.

“I told you about ignoring me,” the man warned.

“I don’t know,” Bastian answered. “I ain’t never been for sale and don’t imagine how you can put a price on a person, though I know some people do.”

“On the contrary,” the man answered, directing him toward a pail of water to wash in. “It is not people who do, but the market. People ain’t smart enough. But the market is brilliant, and it can price anything – that horse, you, me, the pail – it makes no difference; the market will tell you exactly what everything is worth and will not lie or cheat you.

If you bring to her what she deems valuable, she will lavish you with reward. If you bring her something worthless or not to her wanting, she will taunt you and make you suffer as sure as getting beaten with a stick for squandering her time.

“You she wants, and knows exactly what a healthy seventeen-year-old Negro is worth. Tell me now if you have any skills that should be considered, because, like I said, I hate to be cheated. Besides, I think every man should have a clear idea what he is naturally worth.”

Perhaps it was from youthful pride, or perhaps he had fallen under that man’s brainwash, but Bastian answered him. “I was born free and am skilled at gunmaking.”

The kidnapper sucked his teeth. “Do you make shaky Negro guns or the good kind?”

“Me and my papa make the truest guns in three colonies. You can ask anybody that know guns.”

“Yessir,” his abductor said delightedly. “The market will know what you’re worth. Now me, I am only bold, and many men are that, but you are skilled at something there is need for, so I daresay you will go at a premium. You should be proud to be worth something. Tell me, what do they call the guns your daddy make?”

“They go by his name, Bastian Johnson,” the boy answered. “Same as mine.”

Upon hearing this the man whistled. “You are valuable indeed,” he said, taking his own pistol from its holster and showing it.

“I see you ain’t mean as you look,” Bastian replied brazenly, when he saw the pistol, as he put on his new clothes and followed his abductor out of the barn. They hitched the wagon again, then drove to the courthouse steps, where twice a month an auction was conducted.

When his turn came to go upon the block, Bastian was rigid with fear as the man who had taken him from his home announced his skills. “He is a seventeen-year-old Negro boy of fine build and exceptional skill. Owing to his good character he has never been touched by the lash, and he is a master gunmaker already, a skill he learned from the renowned Bastian Johnson.”

A murmur went through the crowd when the auctioneer mentioned this, and the bidding for him did indeed open with a frenzy, until a voice from the crowd called out, “That child is free and has been stolen from his family.” It was his Uncle Goodwin, out of breath as he came into the square.

Bastian had never been so happy as he was then to see his uncle, who had come to save him, and nearly cried like a child.

“You watch what you say,” Harris cautioned, pulling his gun from his waistband and pointing it at Goodwin. “His father owed money and sold the boy to pay his debt.”

“That is a bald lie,” Goodwin said, walking toward Harris.

Harris cocked his pistol, daring Goodwin to come any nearer.

“On what grounds are you calling this man a liar?” Someone challenged from the crowd.

“Because his father is my brother Bastian, who many of you know, and he would never do such a thing. First of all he has never had debt in his life, and secondly that’s the last way he would try to pay it.”

Now many of the men knew both Johnson brothers, and they began to discuss vigorously how everything should be allowed to play out.

“Do you have a bill of sale?” The auctioneer called to Harris.

Harris, who had long practiced his thievery, produced a forged document, which the auctioneer took and examined.

“It looks authentic to me,” the man announced. “The sale will proceed, Mr. Johnson.”

Goodwin, along with several members of the crowd, was outraged, but he had no choice. When the auction resumed, he joined in the bidding against the others for his nephew, torn between looking at the boy to comfort him, and not wanting to upset either of their emotions.

Goodwin, like his brother, was a trained craftsman, who made a decent living for any man, and he had ready enough cash. After those who were not serious about buying fell away, his chief rival in the competition for his nephew proved to be a colonel from the Royal Army. Against him Goodwin bid all he was worth, and all his brother was worth. When the man did not drop out of the auction, Goodwin kept bidding what he thought they might reasonably borrow from friends. After that he bet what was unreasonable, but the colonel was unmoved. He had entered into the contest to buy the boy and he intended to have him no matter the price. As Goodwin neared emotional exhaustion, the colonel looked at him coolly and could tell he was beyond his limit. He added then a thousand pounds to Goodwin’s last price.

It was exorbitant, and a murmur of shocked disbelief spread across the crowd’s lips, but it was the final price set fair by the market. Goodwin was defeated.

He looked at his nephew and began to weep on the courthouse steps.

The kidnapper Harris gloated perversely and said to his former property, “I told you you was worth more than me, boy.”

As the auctioneer swung his gavel down, Goodwin Johnson pushed his way through the crowd toward Bastian, and everyone parted to make way for him. When he emerged from the throng, though, instead of going to his nephew he charged at Harris, his fists ready for a fight. Unfortunately for the poor man, he was dealing with a rough sort who knew the use of a pistol better than he. He was outmatched again, and for the last time among his days. Harris, when he saw him coming, fired but once from the pistol. It was true and Goodwin fell to the ground.

Amidst all this, the colonel paid the bursar of the court, and the sum he turned over that day was the second highest ever recorded for a slave in that colony.

The highest price was the one Rudolph Stanton’s father had paid for his mother, who everyone said was a countess abducted from the court of the Ottomans, or else the consort of a pirate king from the Barbary Coast, or, more outlandishly, even the queen of Dahomey herself.

That she was noble was as certain as that she was a slave, and later she refused to reveal her origin from shame that her house could not redeem her.

Wherever she was from, she was queenly haughty and even the block could not steal that from her, and when the elder Stanton paid it was with a suitcase that required two men to lift it up, inside of which was naught but pure gold.

For Bastian a lesser sum was required, but the purchaser was no less pleased with his prize as they left the market.

three

The day after Mr. Johnson discovered what happened to his son it seemed the entire Negro population, free and enslaved, learned the boy’s fate at the very same time, and all began to descend on the Johnson house as if a call had gone out.

The Johnsons were not surprised when their nearest neighbors showed up, or when Bastian’s friends came to grieve his absence. And when the Darsons and the Merians arrived it was only slightly out of the ordinary, as both of them had boys Bastian’s age. However, when people began to arrive from as far away as Chase, and then from towns at the far edge of the county, they were caught completely unawares, but sensed something extraordinary was occurring. By that night their relatives from as far away as Knowleston had arrived as well, and the house overflowed with people, including a few who came only to see the scene of such misery.

All were welcomed there regardless of why they came, and there was a great gathering then of all in one place, such as had never before occurred. Mr. Johnson’s house was not large, but it was able to accommodate everyone who streamed in from the shops of the town and the surrounding farms that week, as they heard Bastian’s story. They came with gifts of food, pots of liquor, and instruments of music making such as those who played them thought appropriate.

As the adults congregated inside, the young people gathered in a yard outside the house, where Caleum and Julius sat at the center of the group telling the story again of their last afternoon with Bastian. “He was here headed home one minute, just like the two of us, but never made it,” Caleum said, for the tenth time that afternoon.

All of the young men then began bragging about what they would have done had it been them, while the young ladies thought Caleum and Julius must have done something very clever or brave to have made it home. Caleum and Julius knew, though, it could have been either of them just as easily, but for chance.

In the midst of all the attention, Caleum saw a young woman he found especially pretty, before realizing he had met her before when they still attended Miss Boutencourt’s school together. She had grown very much since then, and it was difficult for him to keep from noticing her too obviously, but he forced himself to tear his attention away as soon as he realized it was George and Eli’s sister, Libbie Darson.

The girl knew of the fight her brothers had had with Caleum, and their hatred of him, but as she listened to him that afternoon, and watched him move among the other guests, she forgot about loyalty to her family. Whenever Caleum said something she agreed with, or that agreed with her, she made her approval known with an open smile, and when food was served she conspired to be the one who brought him his plate.

Caleum was disarmed by this gesture and even lowered his shield enough to return her smile. After that, and throughout the meal, he allowed himself to gaze at her openly. She had hazel eyes larger than any he had ever seen, and her skin was the hue of a chestnut’s inner husk, though smooth as polished walnut. She was the tallest of all the girls gathered, but her height did not detract from the well-balanced proportions of her shape. When they stood next to each other after supper, he found himself looking directly into her eyes. When he did, as the other young people gathered round the musicians, Libbie turned her head away in embarrassment, being unaccustomed to the feelings he provoked in her.

He was not used to them either, but he knew them for what they were and did not shy away. “Meet me tomorrow on the north side of the square,” he said, when no one else was within earshot, although all could see them in conversation.

Before she could answer, her brother Eli came and took her by the elbow, neither looking at Caleum nor avoiding him, simply leading his sister away without another word. Libbie did not resist, but she felt a sinking in her breast as she moved away, like a jewel falling to the bottom of the ocean. Caleum felt this loss as well, when she left their conversation, but his was twinged by renewed anger at her brothers.

That evening, when all the guests finally left the Johnson home, he was still in turmoil as he headed back to Stonehouses with Magnus and Adelia.

Seeing him still out of sorts the next day, Magnus tried to comfort the young man.

Adelia, however, could tell immediately what else was bothering him. “I don’t think it’s just Bastian that has him feeling so,” she said. Magnus was about to ask what she meant when the statement made itself clear in his head. He laughed slightly and shook his head. He was going to tell Caleum not to go falling for the first girl he met but thought better of intervening.

“Who is she?” Magnus asked.

“Libbie Darson,” Caleum answered quietly.

“I thought you had strife with the brothers,” Magnus reminded him.

“The brothers ain’t the sister,” he answered.

“All the same. Are you old enough to court, in any case?” Magnus asked next, giving Caleum the chance to think about the question.

“It doesn’t all have to happen all at once,” Caleum answered. “We can take our time about it.”

“Do you want to court her then?” Magnus wanted to know, trying to determine in his head the advantages and minuses that particular union might make.

“I need to think about it some more. I will let you know what I decide, if you trust me to,” Caleum said, being both straightforward and mature with his uncle, to the relief of Magnus and Adelia. “I understand what is involved.”

He was not so moody in love as his uncle and father had been, but forward and direct as his grandfather. He did, however, wonder to himself, even as he rode into town to meet her the next day, whether he ought not turn back and seek someone more prudent to give his affection to, or perhaps wait until a later time to do so.

Their meeting, when it occurred, was exceedingly short and formal and without hesitations. They met at the northeastern corner of the square and began a conversation of pleasantries, followed by Caleum telling her that his parents had left him as a child in the care of his uncle and grandfather, that his ambition in life was only to increase the success of Stonehouses, that he liked fishing to relax, and his favorite meal was spring rack of lamb.

She responded that she was learned in reading and writing, as he knew; she was also a good sewer and needleworker, and that her mother already let her have a sizable hand in running their house. She was bright in her disposition, as he always remembered her being, and if she had any pressing concerns she did not let on.

By the time they arrived in front of old Content’s place, on the southwest corner of the square, they concluded their conversation, and Caleum went home afterward to tell his uncle he did indeed wish to enter a courtship with Libbie Darson.

When Magnus received the news he was very worried and not at all approving as Caleum had hoped. In fact he told his nephew he thought it foolish. No matter how mature Caleum was in many ways, seventeen was uncommonly young to begin a courtship, and he did not want his nephew to live to regret a youthful decision, made in haste, about something so important as who he shared his heart and home with. Out of respect for the young man, however, in the end he concluded that it would be best if they both considered it overnight and reconvened in the morning.

Adelia, being more romantic about such things, claimed it was possible that Caleum, young as he was, simply knew his mind in that way already. “Or would you rather he go about it as you and your brother did?” she asked her husband pointedly, as they lay in bed that night.

“I think you should better hold your tongue now,” Magnus said in reply, being unusually harsh with her, especially as theirs was a relationship in which love, when it was finally allowed to flow between then, did so without cease.

All the same, trusting her judgment, he found himself swayed by the argument, and not unrelieved the next morning when Caleum said his mind had not shifted during the night. After breakfast, then Magnus saddled his horse and went alone to call on Solomon Darson, Libbie’s father.

Mr. Darson was not much in touch with the domestic goings-on of his house and was surprised when Magnus announced his purpose. Still, it was a pleasant shock, and he was happy to receive the visit, for his daughter was at a suitable age and Stonehouses was quite a desirable place. Magnus then offered terms, should the courtship end in marriage, and named the dowry he expected in return. He could not help adding a premium to the amount, both because of Caleum’s tender age as well as the size of his eventual inheritance. Mr. Darson, who was normally quite garrulous and loved nothing so much as to argue and bargain, grew quiet when he heard the price but agreed quickly, if not enthusiastically – because he understood in the end how he was benefiting. He also delighted in his ability to pay such a fee.

Magnus concluded by telling Solomon Darson he thought a long courtship might be best, as Caleum was still young. Mr. Darson, who was more than a little obsequious toward Magnus, agreed that the courtship should be as long as he said, and offered his guest a drink in celebration, which Magnus declined.

His terms settled, Magnus stood to leave without ceremony, but confident in his position as the stronger party in the negotiations, and asked for his horse to be brought out from the stable. Before he left, however, not wanting to give offense, he thought to make a bow to Mrs. Darson and shake hands with her husband in front of her, warmly enough that they seemed like old friends who had just finished dinner instead of a business deal.

When he returned home Magnus called Caleum into the parlor and told him he was free to begin courting Libbie. Caleum, when he heard, sat up in his seat very straight. Instead of fear, which Magnus had been half expecting and half hoping to see on his face, the young man seemed self-assured and smiled at his uncle as he thanked him. “I know you don’t think I’m ready yet, sir, but I am.”

“I still think you would be better served to take your time with all of it. If she has your heart, it won’t go anywhere.”

“I’m not anxious about that,” Caleum said precociously.

Looking at him in that moment Magnus saw the same confidence Purchase had always carried with himself and was proud of his nephew that he had inherited that quality.

“All the same, it’s my business to shepherd your affairs, and I would be failing you in that if I advised otherwise.”

Caleum, ever dutiful, could see then how much his uncle had worked to be a good guardian and felt himself lucky to have such a parent in place of his own, who had abandoned him. Still, he knew his own mind and thought himself well prepared for the next phase of shepherding and guarding himself as well as a wife.

He called on Libbie at the end of the week, riding his horse through the tumult of autumn colors as first frost descended into the valley from higher up. When he came up the narrow way to their house, Libbie, who was in the parlor, saw him and left in an excited rush to prepare herself. It was no coincidence she was at the window, which had no glass, only wooden shutters, and still stood open at just that time. She had been lurking about there the entire four days since Mr. Merian had come to see her father.

When Caleum knocked at the front door, Mr. Darson himself opened it and welcomed the young man into the house. The two of them entered the parlor together, and the entire family was there. Caleum greeted each in turn, even Eli and George, though more distantly.

Similarly, George and Eli were forced to defer to Caleum when they saw their father treated him like a grown man and equal while he still treated them like boys. It did not sit well with them, but they were without power to affect the situation for the time being.

“Libbie, why don’t you show Caleum your embroidery,” Mrs. Darson recommended, after he had sat down. “Libbie is very accomplished at needlecraft and sewing.”

The girl, suddenly shy, smiled downward and sat without moving for a moment, before gathering herself to go off and fetch the things her mother suggested. She returned with a square piece of cloth she had decorated for a pillow.

When Caleum saw it, he thought it was artful indeed and complimented her on it. “It is so pretty,” he said, looking her in the face until she turned her head downward again. “It’s going to make the prettiest pillow in the whole county.” He looked at her for a response, as she continued to smile into her own lap for embarrassment of looking at him directly.

“Why don’t we all leave them so they can talk together a spell,” Mr. Darson told his sons, standing from his own seat.

Caleum stood until the family had left the room. When he and Libbie were alone, he sat down again closer to her. “How did you learn to embroider so well?” he asked, grown more awkward when they were left alone.