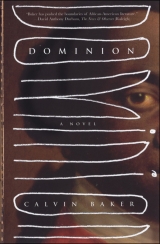

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

“Well, we thank you for it, friend,” Merian answered, as he coaxed the animal back onto the road and they finally turned toward the square. The animal finished the apple in two great bites and began to trot again. In its mouth the taste of fruit was ancient and sweet.

three

The spring when he was released into the company of manumitted men, all were told by court and legislators they could not remain in the colony but had to leave under penalty of death. Those who did not hide and ransom their lives to chance in order to stay near loved ones and old ways joined the lines on the roads heading north and west at the beginning of the year. The month when he set out had been marked by pox, but it was very mild that year and put in check before too long, so that only twenty thousand souls died in the season. It was this fever and dying that he would associate with springtime for the rest of his days. On the square that morning it was brought to mind as bile welled in his throat and he tried to turn it back down, to force himself into better spirits before the Sunday service.

He dismounted outside the tavern and tied Ruth Potter to a railing, then straightened his shirt and went across the square to the little building that served as a church. He was met at the door by the sound of communion and found Content and Dorthea among the milling crowd, enthusiastic to see him as they attempted to banish any possible ill feelings from the previous Sunday. Merian nodded warmly, acknowledging that their fight was now behind them, and followed the couple into church, where they took a pew in back. Some who noticed him there a second week tried to be more generous in their gestures toward their outland neighbor. There were of course also those who did not. He took both sentiments in stride as he sat on the bench and listened to the Easter service.

That week was a different preacher than the one before, and his talk was all of schisms and something he kept calling Utopia, which they would build right there in the newbornland. The sermon was a towering success, and everyone brimmed afterward with talk of this grand enterprise the preacher kept calling by that name all the rest of them seemed to know. The idea, at least in its rough form, was not unknown to Merian, but the word itself was new, and when he asked about its exact meaning later he was told it was a vision for the perfection of place. He smiled with pleasure, savoring its optimism. It was years before he found it also meant nowhere.

“I am building a utopia in the woods,” he said, later that afternoon, when he was introduced to Dorthea’s cousin, Sanne.

“Are you now,” she asked, with bemusement. “And how far have you gotten with it?”

“Oh, I’d say about as far as that preacher,” Merian answered, his face atwinkle.

Sanne cast her eyes downward, then looked across the room, where Dorthea was busy attending to her other guests. “I had better see if my cousin needs any help,” she said, and with that slipped out of the range of his admiration.

“I see you met Sanne,” Content remarked, when he found Merian in a corner off to himself, appraising the room.

“I did.”

“What did you think of her?”

“She is lovely,” Merian answered, holding in check anything that might appear overeager. “Is she married?”

“Widowed,” his friend answered. “Since a year ago.”

“How many children did he leave her?”

“They had none.”

“That must be very hard for her,” Merian said, looking out into the crowded room and trying to make sight of her. He said nothing else but felt a growing wave of empathy for the woman who had suffered what everyone he knew seemed forced to bear: to be widow or widower or else orphan – as he himself was – or in some other manner bereft of kin and mooring to fellow beings. It is simply how things go, he thought, and no use complaining over it.

When Sanne gathered the courage to look over at him again, a sadness sat on his face that made her want to reach toward him but also to draw away, for she could not read what was behind it and distrusted any emotion in people so close to the surface.

What if he is in his nature just a sad man? she wondered. She could imagine few worse things than to be perpetually phlegmatic. It would be worse than a curse, she surmised. Not that she herself was all light humors, but she believed in governing what was willful or overstrong in Nature.

When he caught sight of her staring at him, Merian flashed her a smile of such easy warmth she could not help but beam brightly in return. Why do the sad ones always have such lovely smiles? she thought to herself, starting to smile about the corners of her mouth almost involuntarily, though there was nothing insincere in her gesture.

Before he left that afternoon, Merian made his way purposefully toward her. “We did not talk as much as I would have liked,” he said, “but I hope I might happen to see you again.”

“I will be back for Whitsunday,” she volunteered.

“What is that?” he asked, knowing neither what it meant nor, more important, how far away it was.

“It is also called Pinkster. Seven Sundays from today.”

“We never had that where I grew up,” he told her.

“It will be a grand carnival.”

“I think I would enjoy that,” he answered, and took his leave, much better pleased than the Sunday before.

As he made his way home on the western road he watched the sun beginning to set over the countryside and its final plunge of red intensity over his own land. I am building a utopia in the wilderness, he said to himself, quite satisfied, as he egged Ruth Potter up the hill to his front door. And his spirits were so lifted that it did not seem so much like a joke to him as a thing he might actually achieve.

His first year he had approached the farm with all the enthusiasm of a new transaction, but he went to work on the fields that spring with a new confidence and even greater energies than the one before. As the first shoots of his crops poked forth from the black soil, his diligence toward them was unflagging. He was not grumpy when he rose in the morning to go out, but eager, and he worked through the day sustained by this same feeling. He found himself hopeful in ways he had not dared express before, even in the final days of his servitude. He thought often of the woman he would meet again at the new holiday and imagined her within his rooms. It was greatly relaxing to his mind, and he would fall asleep with romantic notions he had not entertained since his separation from Ruth.

When Whitsunday came, he dressed in his clean shirt again and saddled the mule, then climbed astride, carefully guarding a bouquet of wildflowers in one hand. Outside of the settlement, the mule slowed down in front of the house where it had paused before, but he was able to keep control of it this time and persuade it to continue on. The animal obeyed and carried him on into town, where they stopped outside the inn and rested.

Merian dusted his shirt, rearranged the flowers in his hand, and went inside. The first person he saw when he opened the door was Dorthea, and he found his courage leave him, not knowing what was proper behavior under the circumstances.

“Merian, what pretty flowers,” she commented when she saw them.

“I am glad you like them. I thought they might look nice on the table,” he answered, thrusting them at her.

“Sanne, look at the lovely flowers Merian brought from his place,” Dorthea said, drawing out her cousin.

The other woman came over slowly, cautious both of him and of seeming too bold. “They look wonderful,” she offered stiffly. “What are they?”

“Why, they are utopia flowers,” Merian answered. “You must see the place I picked them someday.”

Dorthea looked at her cousin with a sidelong glance from a corner of her eye, but Sanne cast her look away in shyness at Merian’s offer – although she did not fail to smile.

“If you keep asking, perhaps I will,” Sanne replied at last, before hurrying away across the room on an invented errand.

Throughout the afternoon the two of them went on to trade nervous and youthful looks when they thought no one else might notice them. During songs they gazed at each other more brazenly, staring directly across the room as they sang. It was a joy for him to hear songs sung he had not heard since his childhood, as well as those altogether strange to him, which Sanne said she learned as a young girl.

At the end of the evening he bid her good-bye and asked again when they might next meet.

“I am staying here for a few weeks,” she answered. “You can stop by when it pleases you.”

Merian promised to visit, and even though he thought they had gotten on well, he was careful not to presume that the invitation meant anything more than that.

That evening, after their guests had departed, Dorthea and her husband questioned their houseguest good-naturedly but reminded her all the same how little they still knew about Merian and advised her to proceed with what care she thought due.

“How much do we ever truly know about anyone, other then the way they strike us ourselves?” she asked, but said no more.

Husband and wife looked at each other across the table. Both, however, allowed she was a grown woman and said there was nothing more to be argued. Still, they reminded her again it was her own self at stake.

Two days after the celebration, Merian found himself in town again for reasons scattered and varied, and after buying supplies he stopped off at the inn to call on his friends. As it grew late they invited him to stay on for dinner, out of politeness, and were genuinely surprised when he accepted.

“You don’t have to be in the fields in the morning?” Content wanted to know.

“I suppose things there can get on a bit without me,” Merian answered.

“Why, Merian,” Content said. “I’ve never known you to be slack about work before.”

“A man can’t just work and nothing else,” Merian replied, looking at Sanne. “There are other things.”

The four of them, each with their own ideas, then went out into the kitchen, where the men sat down at table as the women served.

At the end of dinner the entire company found themselves in quite good spirits, and even a bit drunk as the evening ended. “Well, I must get back,” Merian said, bidding good-bye to his hosts.

“It is too dark to be out on the road now, even for you,” Content warned. “Stay in one of the empty rooms and get a good start in the morning.”

“I cannot impose further,” he answered, looking again to Sanne. The widow woman cast down her eyes but smiled softly from the side of her mouth. It decided for him his action and he was shown to the small room he had stayed in many times before.

He had never, however, heard the night there open up with singing, as he recognized through the wall one of the hymns Sanne had sung to him that previous Sunday.

He listened to her voice in long measures of closed-eyed well-being, then sang back softly from his small room the refrain as he remembered it. When their singing stopped, the entire house was quiet and drawn in darkness.

See the man in darkness. He rises and goes to the woman in her quarters, where he gets in bed next to her and bundles in the warmth she gives off under the covers. The woman is stone still and tries to slow her breathing so he will not hear how it catches in her throat or the thump her heartbeat makes under her bed gown. The man hears only this, and his own breath adds to it, coming harder the closer he moves toward her. She is generous fleshed. He is greedy of it but tries to restrain himself. Man and woman lie with each other in the dark chamber and fill it with a muffled paean of wanting that nonetheless does not disguise the expression of what is tender in their thoughts for each other.

It is morning soon.

four

Devotion to Sanne was natural as desire for almost everyone who knew her long. For Merian, though, it did not come so easily and, in fact, did not arrive fully for many years. It was not that he found her wanting for any of the good attributes of her sex, but simply that attachment for him was slow to come always, even to his first wife and own boy.

Devotion to him came slowly to Sanne as well, because they had come together in haste and also possibly that she was no longer a girl but a full-grown woman, with one husband already in the ground. Perhaps this one would also die in her arms.

In fact, not until well after the time that their child was born did she find in her bosom a deep wellspring of loyalty and love for the father as well, and it was said this emotion came then not because of domestic need and convention but because they had donated each from their own personal treasure to the crucible of common creation.

When they first arrived at the farm, after concluding their contract, he showed her those acres he had bragged about before with self-consciousness.

Well it is no utopia, she thought to herself but, when asked her opinion, answered instead, “In time it just might grow to be something.”

She began in those early days, as he had two springtimes before, with the very basic tools of sacrifice and a task before her so overwhelming she found it best not to think of its completion – but rather that each chore was a step whole in itself – so that she might live in small victories instead of constant setback or failure. She was alone then as Merian himself had been in his first days, even as he toiled in the fields beyond the house, which seemed to her like leagues away.

Besides the great mass of dust she found caking every exposed surface in the room there was the matter of the measly fireplace, which was little more than a circle of stones under a too-small hole in the roof, and that circle hardly big enough for cooking with more than one pot. The vegetables he grew in the garden were not enough for proper sustenance, and of household hardware there was nothing but a knife worn down to the thinnest strip of metal and a spoon that looked like it had been used for digging in the dirt. These were merely the things that caught her eye upon entering her new abode. She knew there was likely to be much worse when she started looking, and great labor indeed if the place was ever to be made a home. She set about this self-assigned task with iron resolve, mistressing those things he had failed to master even in his other victories, great and small, in the wilderness miles from the end of the road – and quite a ways farther from the seashore, which was her natural home.

She tried never to feel self-pity or doubt as she contemplated the works in front of her, but simply labored at improving her lot, so that when she finished they could no more properly be called Merian’s acres. That is still how they were known for a time, but from her first day there it was a misnomer.

Inevitably, as she went about rearranging things, the time came when the place also began to show its secrets to her, and she learned what was on the bottom of the lake bed. It was as she did the washing on the shore, at the end of their newlywed weeks, and counted the small victories she had already achieved, that she learned what was the matter with the land that her husband struggled so hard against. She wrung the washing, feeling pleased with her accomplishments, and began pinning it in the trees, when she suddenly heard the sound of Ould Lowe’s canny voice calling filthily to her. She knew immediately what it was she heard, though she had no name for the specific fiend.

When she broke free of the fearful spell the beast was trying to enchant her with, she marched directly back to the house to await her husband’s arrival. Shortly Merian came round from the fields for the midday meal, and she asked him what kind of land it was they lived on again.

“It is our utopia,” he said, filled with the sweetness of their young union.

“It is devil’s ground,” she retorted. “Now, what is the thing out in the lake?”

“It is vanquished,” he insisted, giving her its name. “At least it was till you come.”

“It is half done, like everything else around here,” she replied, beginning the first fight of their marriage.

They rowed all afternoon, and when he finally considered the argument finished and done Merian went back to the fields. When he left, she went to the corner where her wedding trunks were still stacked and removed the chain that had fastened them together, then went back to the lake, where she found her laundry no longer pinned to the trees but floating out on the water.

After removing her boots, Sanne waded into the lake, calling to the ghost as she went, “I don’t know what you are, but you’ll not haunt this house.”

When Lowe heard his prey and himself spoken to, he reached out blindly to the woman and dragged her by the feet until she was submerged. Beneath the surface of the lake, he pulled her toward him in a ghoulish embrace with his heavy arms, where he might make her his favorite new plaything. Terrified, Sanne struggled to free herself of the monster’s grasp but could not break his hold until she was near enough to smell his skin. When she was, she needed no dark arts but gouged at his strange multicolored eyes until he let go of her.

The beast relinquished the woman only with hesitation, even in his great duress of pain, and churned at the water in anguish. Once he had relinquished her, Sanne took the chain she had brought with her and bound him, arm and leg, then shut tight a lock around its links so he could no more harass her household. When she had finished, Lowe sat alone on the bottom of the lake, restful as a monument of one in heaven.

She returned home that evening, satisfied with her work, to find her husband waiting for her to make his dinner. “And who cooked for you before?” she wanted to know.

“I did it myself,” he answered.

“Then it is not so long that you have forgotten how.”

“You’re not going to feed me?”

“Isn’t it enough I left my home for you?”

“I gave you a new one.”

“It is filled with bad omen.”

“It is virgin and must be tamed as all land like it, if we are to have a place.”

“I once had a home.”

“You are free to go back to it.”

“And what waits for you to return to it?”

So continued their fight until she barely had voice to speak. “I left my home for you,” she said again, before falling asleep, not knowing what future her union to him held or what future of any kind she might expect anymore.

The land, though, was finally free then of the tyrant Ould Lowe, for he had finally been toppled and no more would he be heard singing in springtime.

The monster himself, who had roamed those forests since time out of mind, rested then in silt, among the weeds at the bottom of the lake, twice slain and no longer a force to haunt human habitation. His titanic head curls against his chest and his spine folds to meet his feet as a child in the womb of the world. He will rest near silent almost a hundred years.

In the days after their fight, Sanne rose in the dark hours while her husband still slept, prepared breakfast for herself, then cleaned the dishes and went off onto the land to dig stones for her oven.

When he found a decent one, Merian was always certain to bring it back for her, but by this labor alone it would take all year before she tasted bread again, and she was determined to have it sooner.

Before midday she ceased and headed back to the house to prepare his supper. When both had eaten she went back to her work, hauling the stones she had dug up to the back of the house. There were nearly enough for the belly of the stove by midsummer, and all she needed was another stack for a chimney. She still could not believe he had lived in his little room for so long without a proper stove for cooking. She knew from her last marriage, though, that the natural state of man with woman, or woman with man, was turbulence and strife. Perhaps not always loud and bursting forth from the seams, but it was ever-present nonetheless, as a deep inner spring that stored tension in its center belly and released it, either slowly over time or else all of a sudden, as in the eruptive fights that had begun to curse their young house. Nor was there time enough between their less significant scrapes for things to return all to normal. If she asked him about the stove, there would be no end to the argument it might plunge them into, so she left him instead to his fields and fried bits of pone, but no bread, and did not mention it. She would have bread for herself before the end of the season and began looking for stone for her chimney. If there was bread for him as well, so be it.

In the forests at the edge of their land she found another lode of rocks and figured it would be enough to finish her task. She considered her fortune as she broke up a stone too big to carry with a pickax, and put the pieces into the wheelbarrow. She was a powerful sight as she guided the apparatus through the woods, and there was little doubt that she had in her the will to defeat any other thing that stood in her way.

On the old farm they had said it of her as well, though she could not defeat the death that came and snatched the first one she married, neither with her skills as a nurse nor in sheer combat with the demon god once he came. For Death, she knew by then, is indeed something none can defeat but that Other in Heaven; God is most certainly other, and sometimes the two of Them in cahoots for the same end. She thought of this as she made her way home with the evening load, and how her fortunes had always been mixed in their blessings. But she knew, if fortune had marked her for it, she would master this charterless province as well as she had mastered all the unbalanced ascents and descents before it.

Nor were these her only contributions to the husbandry of the place once she decided to stay. She also wove textiles so that there was new cloth to protect their naked skin from the elements of the season, and then increased the plot of vegtables outside their little room, so there would be enough not only for summer meals but for canning and drying as well, to nourish them properly through the winter months, when all was desolate except for foraging beasts, which seemed to her too hard a way for a person to have to come by their daily meals.

When he happened upon her at midday and saw all the progress she was making, Merian thought himself lucky and wise to have made the choice he did of brides, impetuous as it might have seemed to some onlookers, who did not know them or how their house was beginning to prosper there at the edge of the world.

When he and Ruth Potter went to the settlement on one of their monthly provisioning trips, he thought of all the changes that had taken place since the previous year there, as he nudged the animal on. “Come on, Ruth Potter,” he cajoled, “we got to get home before this time tomorrow.” The animal looked around at the man with its deep willful eyes, then turned its head back to the ground, stopping now and again to take whatever it found curious, before grudgingly moving on under his prodding.

Instead of having to visit here and there for the things he needed, as he did those first years, though, he was now able to acquire all his basic needs from the chandler who had set up in the town center. Although there was no ship to be outfitted for miles around, it was how the owner insisted on styling himself, though he was just a plain dry-goods merchant such as might be found anywhere in the colony. At the inn, Merian saw they had put up shutters to the window, giving the place an air of respectability, so that the streets were in every way becoming not unlike a town still inside of human habitation instead of the end of that rough and desolate road. He began to wonder what else he might see as he sat at the bar of the inn having a pint with Content.

“There is talk that the road might be graded and boards put down.”

“And who will do this?”

“They will hire a man.”

“Who will pay him?”

“The merchants.”

“Business is good on the square?”

“It hasn’t been bad.”

Returning that night he wondered whether his own gains were as much as the merchants’ on the square and whether the little farm would keep up. He had paid that year for his goods one quarter more in hard cash than the year before.

At home he climbed into bed next to Sanne but did not mention these things.

“How is the oven coming along?” he asked her.

“It should be finished before summer’s end.”

“And everything else?”

“That’s a fair amount. Hard to say when all of it might be done.”

“And with you yourself? How are you getting on here?”

It was the first time he had ever inquired about her general well-being since they were wed and he had brought her out there. The small tenderness moved her to forgive him certain other things, so that the coil which had been tensing day by day found release in the open atmosphere that night, where it was able to let loose of its stored energy without harm. On the contrary, it was energy that manifested itself in the same tenderness with which they sang to each other that first night, so that the early days of their marriage were not all full of strife and turbulence but also of the bliss that marks happier houses, when their inhabitants are so wise as to give it free reign. No, they were not Merian’s acres alone at all anymore. Nor did he see them as such.