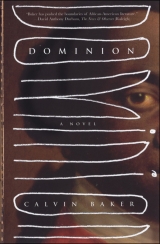

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Calvin Baker

Dominion

For Ariane,

Gift of Paper

I. chronos

one

They ate the dead that first winter on the land, such was their possession by vile hunger, mean desperation, and who can say what else, other than it was unnatural. Any decent history will vouch for the truth of that. And, according to lore, the majority of the graveless sacrificed were uneasy souls, who walked certain nights on top of the earth – haunting not just the ground of their defilement but all the contiguous lands – until they possessed the entire continent as surely as if they had been more fortunate in life.

Ould Lowe, one from that legion of unblessed, had prowled the wilderness since anyone could remember. Each Sunday he could be seen standing atop the hill on the southern side of the lake, ululating as any wild beast, or grief-stricken man, from the first moments of creation.

It was why the land was sold to him at all, because to put up a proper house there he would have to begin construction on the very spot of the ghost’s weekly sojourn. Surveying east and west; north and south – to the edges of the horizon in each earthly direction – Jasper Merian sought a better place, or some compromise that would give him access to his lands without disturbing the unburied. He could see no other way, though, so started digging where he was forced, out there on the very boundary of civilization and silent oblivion. He was not generally a man to go against common sense or community, but this was all any would give him to purchase or settle when he finished his term of servitude.

Nights he went back to the outpost to sleep, until a half-proper roof had been put up out in the forest, over the little shack he had managed. The villagers all stayed away from him once they learned what he was doing out there, but he did not mind. Or rather he learned to show no sign, having concluded in earliest youth certain things about the inner levers and measures of assembled man. There was besides nothing else he might do about it but continue his building.

As for the ghost, he had not yet seen him. Nor was he bothered in the way other men might have presumed to be when he finally did catch sight of the fiend. For when his own forebears arrived on the land, not many years after the first settlement, God had already been brought in to tame the heathen new country – so that superstition and minor deities, along with pestilence and death, dwelled only in shadow and certain corners too mean to allow Him entrance. Over time, so say the writings, other gods would be imported as well, and all stand atop the aboriginal like a totem with none except true God at its sylvanite apex. This was He to whom Merian principally paid the respect of prayer when he paid it to any at all. Owing in large part to this, he saw no need for fear. For another thing he had borne the spirit no insult and looked on his presence not as divergent but an extended part of the numinous world.

When the roof was sound enough from the elements he slept out there his first night, still unafraid. It was Saturday and, if there was anything to lore and ancient saws, Ould Lowe was said certain to be visible in his full horror and abomination that next day. Merian stared out at the stars through his unfinished roof and despaired of other things, but banished them from his waking mind lest he thwart his own enterprise before it was properly begun. As for ghosts, he gave no more thought at all.

Morning was his first on the land, and he rose in the still darkness to make his way to the ceaseless work of clearing away timber for fields and digging rocks from the soil to increase its fertility. They were onerous tasks that on a proper farm would have been distributed among many. He toiled in solitude and did not swear oaths or otherwise complain.

In the small clearing he had already claimed, Merian raised ax to tree and listened to the sound echoing around the forest. He smiled, knowing it was his own woods and, as far as that sound could be heard, more than likely his own trees and property as well. Merian’s ground. After this ceremonial first blow, he rolled his sleeves and heaved the ax again, relishing the sound of his effort each time as it rang through the woods, like a shot from a musket, until the energy of his labor was so great that it deflated even this small pridefulness. He was mute as the wood creaked against itself, before crashing to the earthen floor of the forest, exhausted amid a thick storm of dead leaves and debris.

When the great oak finally gave way to his hand, Merian could not contain his vanity and surveyed the increasing space he was creating in the woods, beaming broadly as he imagined with preening care where each field would lie, and each barn, after the main building was finished. None could stop him from dreaming then, as he looked upon his lands and shone like a newborn constellation in the early evening sky. He was twenty-nine years on earth and three months a free man.

It was as he walked over to the downed giant, to clear away its limbs and prepare it to be made into rough boards, that he saw Ould Lowe the first time. Rather, it was then that he heard Ould, for the fury and passion of the creature’s wailing caused his heart to stop still in his chest and his blood to run backward through him. When he had recovered enough from his first shock, and gathered courage to raise his head and look upon the beast, it was just as the writings claimed. The specter stood not five paces from the future doorway of the settlement, and held in one hand a great polished walking stick that he leaned upon, having otherwise but one leg to support his immense frame. From his face a pair of deep-set and ill-matching eyes stared out from their withered sockets, each a color and disposition of its frightening own. Merian faced him full, holding the ax still in his hand, and the ghost in turn gazed on the man, holding the staff that supported him in his wandering to and fro between this world and the one not fully known. Neither the living nor the dead moved from the spot where he had staked himself, as Lowe stared the interloper over in appraisal before letting his great bellow curdle the woods again, so that all in town below who heard it knew exactly what strange new sound it was and swore that the fool who bought those cursed acres had met his fitting and proper end out in the Indian wilderness.

“What do you want?” Merian asked, carefully leading the ghost, as he had been instructed, toward a plate of offering he had set out the night before as providence against the creature’s coming. The fiend, when he heard Merian speak, began to laugh at his ignorance, as the last to dare address him so boldly was well versed in the left-handed arts, and what even he received for his courage was a fate worse than that of Ould Lowe himself.

When Merian repeated his question, even at once with the ghoul’s laughter, Lowe walked to within inches of him, then leaned in closer still and began to swear a string of obscenities that burned in the man’s ear. Merian did not move from his spot as the creature spoke but, when it had finished, motioned toward the offering he had set out before. The ghost eyed what was on the plate, made his way toward it – as rapidly as his condition would allow – then seized the platter and flung the thing away into the trees. As it spun through the air he pronounced again his curse over the land and the things that would befall whomsoever should settle there. Merian heard the curse and again approached the creature with calmness, but when Lowe again made one of his violent gestures it sent the man back on his heels in terror and cold blood. The ghost gave pursuit with a quick arm, which Merian neatly dodged and countered with his own fist. The two then locked in the most unsavory embrace and began a fearsome struggle that ended only at the shores of the lake, where their embattled forms seemed as one violent mass. Both were so disheveled, drenched, and unsteady from the effort of trying to master his foe that none looking, had there been witnesses to that epic, would have been able to tell flesh from spirit, body from soul, past from future, or Merian from Lowe, so tangled were they limb against limb in a single coil of mortal and immortal.

When the fight finally reached the banks of the lake, Merian jumped into the water, fleeing from the beast, and Ould came after him in quick dangerous pursuit. This, though, was the man’s wish, having heard that any spirit who finds himself in water will soon become disoriented and lose his way there. He hoped it was true, as the Gospels claimed, for themselves, as he dove under the surface of the lake.

Out upon the water Ould Lowe did lose track of his prey and fast found himself unable to distinguish north from south or east from west. Neither could he tell confidently between the natural world of his haunting and the unnatural world that was his proper abode. In this confusion of watery enchantment Merian resurfaced to cast a stone attached to an old chain he had brought with him, around the spirit’s neck, and Ould Lowe sank to the bottom of the lake bed. There his profane songs could long be heard, trapped between Earth and the Palaces of Death, especially each spring when the thaw came, as he tried to find his way to either one world or the other.

In this way did Merian rid his land of the spirit that had haunted it since the ill-starred first settlement, in ages untold. When he arrived back at the shore, he took the ghoul’s stick and his own knife and began to carve a leg for the drowned ghost.

When he finished he was shivering and graycold, as he buried it under an outcropping rock on the shore of the lake, hoping this was the reason of Ould Lowe’s wandering and that its cenotaphic restoration might bring him peace.

Years later, when his sons wanted to take a certain stone and put it to use as a boundary marker, Jasper Merian would tell them it was no mere rock but a gravestone for the spirit he had battled in order to win their place of home. They would look at each other then, silently, and though both knew better than to say so out loud, in his heart each refused to believe his father but that he was telling stories.

When he had finished his tasks on the side of the lake, Merian went back into the forest and began readying the fallen timber, as if nothing strange or unearthly had happened on his farm that morning. The forest brightened with birdsong, and he worked serenely to hasten the day when he would no longer be forced to sleep half out-of-doors, under the naked canopy of heaven, as he had done so many twilights since leaving Virginia.

Over the course of the summer Merian’s house continued to rise from the floor of the virgin woodlands, and he planted crops in the ground, both foodstuff and tobacco to trade for cash. That summer in the clearing he was master of both masculine and feminine tasks, as there was not yet a mistress of the place to give him comfort in his toil. It was then, in those first days, a sad house even after the roof was completed.

In his private heart, however, he was not without companionship but thought often of the saltwater woman he had left behind in Virginia. He dreamed of her often as he worked outside in the hot months, and he dreamed of her when he lay down at night in the cold first hours of winter. The force of these nostalgic passions took him unguarded, as he had never before known the occult powers of memory so fully but only seen them in others, seized and bound by its invisible teeth and shackles. He himself had never before been separated from kin and home, or had any one thing or place to miss.

He was far away as the other shore of the ocean but swore to himself he would someday return.

He had left behind – more than just the woman, Ruth was her name – a small child as well, whom he could not take with him, as he belonged properly to his mother and her master.

He knew it would be at least a year before he would see either of them again, if indeed he ever did. He planned, though, in his brain and bosom to recross the trail that had brought him out to this forest in time for next holiday season. It was a hard and solitary home in those early days as the roof went up in the clearing, and Jasper Merian was alone in the ancient forest with nary a beast for company.

Jealous neighbors swore that his success, when it came in time, grew from a compact he had made with the same devil who once frightened travelers on the southern and western roads. But he wrestled the wilderness as he did Ould Lowe and the rattling forces of fear, those first days, trying to gain permanence and soundness for his roof and the empty room beneath it. Over years and generations the path crossing westward grew broader, and smaller paths cut back across it in every which direction, so that no place was ever again uncharted or alone. However, Merian then lived pressed against the very boundary of the known, and the two roads were barely new-blazed trails that took the nearby settlement the last provisioning stop before the unknown.

Populations looking over that place in distant years would not know how fearful and wild the woods were, or the bright beauty of light when it reached into the provinces that darkness alone had known when beasts still fought and foraged the ground, before the man claimed it for himself. These, the wind, the shadows, and the light, were his companions as he pitted his wits against the forest to draw out partridge for dinner or else outmaneuver the straggling bear who ventured sometimes uncomfortably close to his door.

When the woodlands went barren and his own provisions also failed, it was the same old bear who supplied him with its sweet meat the last weeks of that first winter, without which he would not have made the spring. The bear was felled with a single ball from the musket, it being old and unwilling to cling too fervently to life, or surely it would have claimed victory over the man in that contest, and lined its own hungry early-waking stomach with human flesh.

After the first of his meals of bear meat, venturing over the property he had purchased, Merian stopped to measure again what was his, arguing with himself the finer points of possession and trying to fathom certain secrets from the webbed, foggy circle of his experience. He asked himself whether that which was half divine on the place belonged to him in equal measure as things like the partridge and cypress. He also counted his own freedom and the depraved fiend Ould Lowe in that same lordly grouping of things and saw how much all of them struggled and bargained against one another, so that his life or another’s, his freedom or his failure, were things that circled about – like-shaped and taloned as eagle’s claws – looking for a place to grab and rip at their natural or made prey, as had always been and would always be on that place. His supremacy on his lands increased something great that morning, and he knew he would not die of starvation or ever allow himself to get so close to hunger out in the forest again. Other monstrosities he knew not the names of, but was certain that they would come as inevitable as hardship. However, having staked so much already to achieve the trove of freedom, he would do anything to preserve and keep it with him. He muttered the name of the fiend to himself and swore that, as he had vanished it, so would he everything else that stood in the way of his well-being and prosperity.

Spring, he set his sights to improvements upon the bare hut and fields he sowed by hand. In order to make the most of what was his, though, he knew two things were indispensable: the first being a good mule, the other a woman. Nor would he let a shortage of funds keep him from either.

To get the mule he saw no other way than to steal it, so woke early one morning and made his way out to those stretches of the trail in the mountains where no law ruled but only strong arms. When night came he made his way toward a camp and untied one of only two pack animals that belonged to the party traveling away.

In the darkness he led the mule over the ridge of earth back to his lands. Morning found the beast learning to bear the yoke instead of other burdens.

In this way he would clear twice as many acres that second spring as he had the first and increase vastly that year his purchase over the wilderness – where he had gone, when none other would go there, to make a home in the world where none existed before him and all said none could be made, to exist and hold him.

For the woman he turned in other directions. At the settlement’s center was a tavern where one of three rooms could be rented by those with no other place to stay the night or, if so happened, the month. This is the same outpost where he had spent the spring before his own roof was yet ready to cover him. The proprietors of the inn were free-thinking people and had been the only ones who did not shy from him when they learned where he had bought and was building. They had even nodded on it as the scientific thing for one in his position who wished to improve it. As he did not see a way to steal a woman as you would a mule, he turned to these friends for advice as to where he might find one who was eligible.

“I am looking for a woman. Do you know where I might find one?” he asked Content, the husband.

The two looked at each other when he put this question out, and at first made no reply.

“Well, you might do as I did,” said Content, “which is to search in the church.”

“No,” Merian answered his friend.

“What do you mean no?”

“That I will not look there. I cannot go.”

“Of course you can. If they are not set up for it, they are certain to make arrangements.”

“That is not what I mean.”

“What is it you do mean, Merian?”

“That I have no faith in that course.”

“Still, you should go there if your aim is a wife.”

two

The man rises half clothed in darkness and dresses himself fully. At his fire he heats yesterday’s porridge for his breakfast, then sets out on his journey. A cold spring rain belts the landscape, and he pulls himself tight trying to keep warm. He is solitary and on his way.

His cold form plows the gray empty roads of Sabbath morning, but he is happy to walk out here without encountering anyone. He holds his thoughts close to himself as the goose bumps on the underside of either arm, which are wrapped around his coldness. He does not consider himself to be making a sacrifice, or ask for special favor or forgiveness from Providence for this great effort in getting to the meetinghouse, but wants only to sit as a parishioner among parishioners and a believer among the devout. He will do this to gain their human company and does not think any more or less of himself for it; certainly he does not think it a thing to speak to God about in the silent talking back and forth that Protestants and Deists do with their Lord, or pagans and hypocrites with their idols.

He wishes for and, in his mind, talks to the mule – whom he could not resist naming after his former companion, his wife, even if there were some who would not agree to that term, as they had not been wed in church or made any other formal arrangement with authority.

He curses himself for not saddling the beast and wishes for its presence. If you were here, Ruth, he whispers against the morning wind, this road would not be half as hard on a body. He wonders now whether he should not turn back and spend his Sunday improving the hut or sorting his grain for the first planting. He frets over these constant worries, as well as the minor ones that have occurred to him only this morning. What if the congregation judges him in an unkind light and is not willing to have him among them? Or what if there should be no eligible women? He knows he is foolish to have taken Content’s advice. As the rain pounds down on his shivering body, still before daybreak, he thinks again of turning back. It is dishonest, Jasper, he argues with himself. You going to take another woman, and already Ruth back there in Virginia with the little one.

He stops this talk as a terrible creaking sound reaches him from somewhere on the road above, whence he has just passed. It takes him near a minute before he recognizes the timbre of its complaint and realizes it is Lowe, cursing or else singing, from the bottom of the lake where he was fastened the year before. Something has disturbed him there. Merian starts and hurries on his way, lest he have to repeat again a history already settled and past. Who should like to repeat his own story? Merian asks himself. What man can be certain that victories once his would be so again? He hastens on from the sound of Lowe’s voice, picking his steps with less care and greater speed, over the muddy roadway in the first light of Sabbath day.

He reaches the outpost without further incidence and finds his way to the meeting place, opposite the unkempt square. Outside, he stands for a long moment and looks to the eaves and joints of the building, admiring the workmanship, before removing his rain-soaked hat from the top of his head and entering. In the back of the church he finds a seat and takes his place, but does not make eye contact with anyone. Some smile on him, even those who in other rooms would shoot him for his boldness with no further question over the matter than that. He waits for his friends, then begins to grow angry at Content for not coming, feeling even greater betrayal when a hand seizes his shoulder, making him startle.

“Welcome.” A voice greets him. It is the preacher, and Merian nods his head in an idiosyncratic bow of acknowledgment that moves three fourths the way down his neck before quickly accelerating the last quarter bit, and snapping back to forward attention. He does not remove his gaze from the room the entire time, nor, when the preacher goes off, does he feel any more at ease, but regards it nevertheless as an opportunity to take in the compass of the assembly.

The gathered parishioners try to avoid seeming rudeness and avert their eyes when he looks at them, but try as well to seem open to all who would come and worship there. He sees the mason to whom he had occasion to sell some of his unused boards, and the merchant who sold him grain, as well as the smith and some few others he had come to recognize from his winter there in the village center.

Other than those few the faces were entirely strange to him, and more numerous than he seemed to remember the population as being. Their collective impression on him was not unlike the meetinghouse he visited from time to time with Ruth back before leaving, except, if anything, those here were even more hardscrabble and wanting. He surveyed them again and counted his chances for success very small indeed, as it seemed unlikely that any among them might spare even a heel of bread, let alone a grown daughter. And if they should chance upon some generosity, he counted himself near the last who might receive it. His mission already a failure in his mind, he kept his eye open for his friend so he might abuse him openly for sending him so out of his way.

When the sermon finally started he could only figure that the preaching had something to do with the intersection of wilderness and temptation, but then every sermon he had ever heard seemed to have in it something to do with wilderness and something to do with temptation, unless it was the one about kingdom and wickedness.

“We are congregating with wickedness right here among us,” a man from the congregation testified, when the preacher had finished the formal sermon, staring hard at Jasper, as each parishioner spoke in the voice of his guiding genius. “It seems hypocritical to tolerate in the flesh what you would not in words or in the spirit.”

His words went unremarked upon, but all knew they were a reference to their outland neighbor. Merian himself sat rigid and did not need to look at the parishioners to know that their eyes were on him, in either judgment or sympathy. His own emotions, though, clenched up as he tried to contain them. When the service was over, he bundled himself again, made his way back into the unrelenting rain, and started out to his own lands, wondering where else now to find a woman.

On the unpaved road he spied Content and tucked his head into his coat, trying to go on unrecognized.

“I am sorry we were not there, but Dorthea has come down sick. I spent the morning at her bedside,” Content said, after catching up to him.

As Merian listened to these words he could barely look at the man without anger. For the sake of former friendship, he held back from saying that it was an outright lie he was hearing and had walked seven miles through the rain to suffer. He felt a great anger at his circumstances. If he were more prosperous, he explained to himself, there would be no need to resort to desperate works to achieve his ends and desires in the world.

“Let me make it up to you,” his friend offered. “Next week we are celebrating Easter and would be much pleased if you came.”

“It is a fairly long way, especially in weather,” Merian reflected, letting his accusation hang there as Content looked at him. “I will see how it is next week.”

“Well, we would be much pleased,” Content said again. “And I am sure there is bound to be a woman there or two. I know at least Dorthea’s cousin is coming from the coast.”

“I will see what the weather is,” Merian replied. “It is not so short a way for someone walking in foul elements.” At that he took his leave, bundling himself back into a knot of angry shivers and tension that warmed his muscles briefly against the springtime cold.

The next week brought nothing but more weather, and Sunday was the wettest day among them. Under his roof, Merian pattered about, preparing his porridge and trying to decide whether he would go into town or not. He listened to the spikes of rain hammering the boards and, in his own self, felt emotions hard and bitter that the growing season had still not arrived and his fields remained untilled. Beyond this, he felt a deep sense of gnawing discomfort that was not so sharp or hateful as hunger but reminded him of an abiding sickness. He knew it was loneliness that roiled within him, for he had been out on the land over a year and a half with scarce any human company. Still, he was surprised to find it so sharp within himself, for he seldom felt need for association of any kind. He remembered then the celebrations of springtime they had had back in Virginia, and how he felt among them like part of the company, even if he could not always share fully in their belief. If only for the sake of this remembered fellowship, he resuscitated his expectations, allowing that he might join in the Easter Day services and the festivals that followed.

He dressed himself diligently before the low flames, taking from a stool beside the fire his pants, which he had washed by hand the night before and hung to dry. From a box beneath the bed he removed his other shirt and wrapped it around his body. At the flame again he took a piece of glass and a sharpened knife, which he lifted to his throat and began scraping until his neck and face were passable smooth. Outside, he saddled the mule with the harness it wore when he first liberated it from its former captivity and climbed on top of the animal. Man and beast then were prepared and headed down the road combined in a single quixotic form.

At the bottom of the hill he listened again to the ghost, singing with even greater strength than before. The creature’s tortured sound caused him to stopper his ears in fear, with the base of his palms pressed against his minor lobes, as he knew everything that lives, or else half lives, does so on the constant edge of annihilation. There were those who saw this edge and got on with it – that is to say past it, smartly – and those others who looked on it and passed through the rest of life in paralysis of fear. The beast sang its dirge. Merian adjusted himself in the saddle astride the mule and coaxed it into a faster and faster trot. The animal would never reach anything even approximating a proper gallop, but it gained speed enough to hurry him beyond the sound of singing and on his chosen way.

The mule moved over the muddied pathways toward civilization, sure-footed even without the man’s hand guiding its journey, until they neared the settlement’s center. Half a mile from the burgeoning square, the animal came to a flat stop and refused to budge, regardless of goading or the eventual outright violence. The spot where it stood was the railing next to a stone-built house with a plot just inside the fence. Instead of keeping to the road, the animal shoved its head between the slats of wood and began rooting in the garden for whatever might reveal itself.

From the side of the house a man, who had watched and saw this, stepped forth and called to the two of them. “We just planted that ground.”

“I don’t know what her interest is in it,” Merian replied, whipping at the animal’s hide. “You know how mules are.”

“I know that mule,” the man said, walking closer toward them. “It belonged to Mr. Potter, who took his family west last spring.”

“Wrong mule,” Merian answered.

“Well, I would swear.”

“You would be lying.” Merian looked the man in the face, and the man looked away, past him at the animal, then back toward the house.

“I didn’t mean nothing by it. It’s just I had a neighbor with a mule that was the image of that one, liked to root in the same spot.”

“Must be something there that attracts them all,” Merian said.

“Must be,” the man returned, then took a half eaten and moldy apple from his pocket and offered it to the animal.

The mule lifted its head from the soil and nuzzled the man’s hand, taking the fruit from his grasp.

“Mule’s name was Potter too, just like the man. It liked apples nearly as much as yours here.”