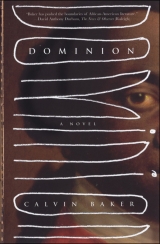

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

ten

Caleum joined Stanton’s militia in October, and they began immediately to prepare for battle. Stanton himself drilled the troops in the beginning, having experience of warfare from the French and Indian campaigns. However, as the seriousness of the political situation grew, he had recourse to hire a seasoned colonel to give the men greater discipline and lead them like conscripts in a full army. Each Saturday they could be seen out on the town square practicing maneuvers, as the colonel lectured them on various theories of warfare. These discourses were sometimes formal, as when he spoke about the use of mobile artillery, and other times they were ribald tirades on the privation of war, or else dissertations on the rights of the colonists. No matter the conversation, though, it inevitably spilled over and continued at Content’s tavern afterward, where the men argued the day’s lesson and often made merry.

To assemble his army, Stanton had gone through all the families in the valley and hill country and picked those he thought were best fit to serve. Caleum knew many of the other men in the militia by name or reputation, but he could not claim friendship with any of them, as they were from so far and wide, and he seldom associated beyond his small circle. Because they had been individually selected by Stanton, though, it was considered quite an honor to serve, and they bonded over their position as the ablest young men in the county.

They were also envied by those men who had not been asked to join, a thing that turned to jealousy whenever womenfolk mentioned the militia with approval. “I don’t think those British would dare show themselves in Berkeley with Stanton’s militia guarding us.”

They were a fine assembly, who feared very little of the sacrifice they were being asked to make and, though young, heeded Stanton’s admonishment to be farsighted enough to ask what their colony and country should be after the strife of war had passed and gone.

At Stonehouses this looming reality still yet to settle, and everything seemed to move and progress as normal for that time of year. In June the corn was high as a yearling, and in July they prepared for the harvest that would soon be upon them. Libbie’s pregnancy was well advanced, and though Caleum urged her to stay off her feet, she was defiant about it – helping with the summer chores as any other maid of the country. Adelia worked her garden, and was trying that year to introduce orange trees from seeds Magnus got for her after they saw Libbie’s embroidered picture. Magnus, as he went to work that season, thought for the first time in years of his past humiliations, first at Sorel’s Hundred, then at the hands of the tax assessor – and also those little assaults that are too small and diffuse to be given name in memory but only stored away. Through this reminiscence he managed eventually to convince himself in the rhetoric and need for war, and that what came after it would outlive what had been before, as everything would be equal in it, and none captive to the major part against his will. It was not something he shared with anyone, but whenever he saw Caleum ride into the stable in his militia uniform his own heart was made very proud, though of course not vengeful or thirsty for blood.

Whenever she saw her boy in his uniform and considered the news that reached them out there that summer, Adelia too had no doubt but that there would soon be a war of some kind. She remembered when Caleum first showed up there on the land with his guardian, Rennton, and how fearless he seemed, as only a small child can be. It was the same confidence that seemed to reawaken in him during that summer, and where before it had worried her to no end, now she allowed it to dispel her natural fears for his safety. She had thought from the moment he came there and became her son that he would always be with her. Now she realized she was foolish as any mother to have ever harbored such hope. She wept in private like an old woman, as it dawned in her mind that he was leaving.

Libbie was even less certain what shape the events unfolding would take and still had hope they might reverse their seeming course. She began in secret nonetheless to make her own war preparations and to craft for her husband a new suit of clothes for the winter months, including a hunting shirt and a greatcoat, the inside of which was decorated with a scene from Stonehouses, with everyone who lived there represented. There was but one face she could not weave in yet, as she had never seen it, but left a space for it to be filled in later.

Caleum himself worked all day long, as if nothing were out of the ordinary, even though there was a weighty congress taking place in Philadelphia that summer, which would determine the future of the colonies. At night, though, heeding Stanton’s suggestion, he would read books borrowed from the library at Acre, which made his positions better reasoned, as he considered what his own future, and that of Stonehouses, should be. He struck on many plans in those days, each of them fired by a sense of new possibilities and in its own way utopic.

Because Stanton approved of his young intellect, Caleum had complete access to the books at Acre and was free to go and borrow a volume even when Stanton himself was not home. Caleum was at first intimidated by the big airy rooms. He had thought when he finished at Miss Boutencourt’s that he was educated, and he had always carried himself as such. In the library at Acre for the first time, though, he felt his immense ignorance hit him like a storm wave slapping an untested vessel. It took all his self-control then to keep from showing untoward emotion, for his first instinct was to cry.

He threw himself at the books with zeal then, so he should be as strong in mind as in body. However, even in his enthusiasm, he took care not to go softheaded with their pleasures and also not to become like some men, who read only part of a book or, worse yet, learned only its reputation, then prattled on as if they had read the entire volume.

He moved slowly through the shelves, letting one book lead him to the next by way of suggestion, so that this folio would take him to that folio and in turn to such and such octavo; from there it was on to a certain quarto or duodecimo, then back to the original folio, and so on. When he could not find a clear answer to something using this method, he was scrupulous in questioning Stanton, especially about Greek or Latin terms.

“Mr. Stanton, what is the difference between a priori and a posteriori knowledge?” he might ask in those early days.

Stanton always answered these questions with the utmost patience and care, so that if the young man was led astray in his thinking it would not be because he had been provided faulty maps and teaching but because he had sought to go wandering in too curious a place.

One day while returning a philosophy text, a slim leather book with gilt lettering caught his eye because of its great beauty. When he removed it from its shelf, he realized it bore the name – Antigone – his grandfather had once told him to give his daughter should he ever be so blessed. Although he was not usually one for made-up stories, he opened the little book, intending to read it. As he gazed at the first line, however, he felt he was doing something wrong. “I have heard this story,” he reasoned to himself. “What if the second telling changes its original meaning?”

Although it was contrary to his usual discipline with books and their information, he had read enough by then to know stories that have been heard or otherwise interrupted were often very different than those seen with one’s own eyes and mind. In this case he preferred Jasper Merian’s rendering, with whatever faults of interpretation and possible misinterpretation, so chose but once ignorance over knowledge.

Once was a powerful king, whom the gods did favor.

Not that one needed books to receive a political education that summer. Everywhere people debated what was happening at Philadelphia, even as they prepared for the seasonal harvest. Slaves, hired men, landowners, and governors all argued among themselves, and sometimes with each other, whether they should break from the mother country and chart a separate course or hold to the path they were on. All men then were expert on the subject, and each held either that war was anathema to their interests or else the only way to secure their rights and rightful consideration.

The debate raged on even after the Congress voted for independence in midsummer. After the harvest games that year, which had become tradition, Caleum and Magnus drove into town to buy such winter supplies as they could not produce themselves on their farm.

What he paid that year incensed Magnus, as there was a tax on nearly everything he needed, which cut deeply into his cash profits. After loading the cart with wares, though, they headed to Content’s, to forget the labors they had just completed, as well as the sting of giving money for nothing in return. The tavern was emptier than was usual for that time of the year, and the two of them sat looking out on the square in reflective silence for quite some time, before Magnus said to Caleum at last. “You know I will die some day.”

Caleum was at first taken aback by this pronouncement and wondered whether something was the matter. “Are you ill, Uncle Magnus?” he asked, with gravest concern.

“No,” Magnus replied evenly, drinking from his mug. “But I will die one day all the same.”

Caleum thought about it for some time again before answering. “I understand.” They continued drinking their beers in silence for a while, before Caleum asked, “Do you think they will rebel?”

“I don’t know. You?”

“I suspect.”

Magnus was thoughtful and withdrawn into himself then, reflecting on all the change he had seen and the change he knew he would not see. It was true that he was not ill, at least not in any immediate manner, but he had been aware since that spring of his mortality in a new way, and the mortality of their way of life as well. He wanted to impart some sense to Caleum of how it was, how it had been for him and his father – and Caleum’s own father as well – when they were all there on the land together, and what Stonehouses was for all of them. He settled instead on asking, “Do you think the eastern field is getting overworked?”

“It would not hurt to rest it,” Caleum answered. “But it is still good land and only needs fertilizing and a rest.”

“It was always the most productive field.”

He asked next after Libbie and her condition.

“She will not stay off her feet, though she is otherwise well and good,” Caleum replied. “She says she isn’t due until September, and might as well do now what she won’t be able to then.”

“Well, I suppose you have to trust she knows best in this.”

“I suppose so.”

At last he put forth his question about the militia, very casually.

“There is nothing new to report,” Caleum answered, “but Stanton has us drilling in secret now, so I think he knows something we do not.”

“He is always first with news.”

They returned to the discussion of the past harvest, then finished their beers and went outside to claim the wagon. Magnus mounted on one side of the vehicle very carefully, and Caleum took the reins on the other, neither of them self-conscious or apologetic about his age, yet both enjoying where they were in life at that moment. They rode leisurely then, back to the country, stopping to enjoy the great swells of greenery and lushness and the fields all under cultivation. When they arrived home, each of them went to his own place feeling somehow they had had a very meaningful conversation that settled something of great import that day. As each ate dinner with his wife and discussed his plans, both knew that the future would arrive only after a rupture with the past. That is the understanding that had blossomed between them, that they were in the final moment of that shared past, and as for the other part – what the future would be – that would be decided only in time. For what it was, though, and what they themselves believed in, they were very clear on that.

When Libbie gave birth in November it was a daughter, and Caleum was finally able to honor his promise to his grandfather by giving to her the name he had asked him to. Libbie, however, when Caleum told her the story of where the name came from, insisted they give her another as well, “Because we don’t wish for her too many sorrows either.”

She suggested at first that they call the girl Lucky, but Caleum, being superstitious in such matters, thought that was too tempting of fate. Instead they agreed together on Rose, which was the name she was known by the length of her days.

In the weeks immediately after her birth they did not have the kind of celebration they had before on such an occasion, but at Thanksgiving that year mother and child were foremost in everyone’s prayers. The other great topic, which was now ever-present before them, was the fighting that had broken out in Massachusetts between the colonists there and the Royal Army.

Caleum and Magnus were both ardent supporters by then not only of Berkeley, but also of independence in general, and Caleum continued to drill with the militia that winter in anticipation of being called to serve. It was then that he remembered the sword his grandfather had given him. When he went off to battle it was this weapon that would serve him best. He would also wear the coat Libbie had made for him, with the scene of Stonehouses on its interior, and that was complete now with the birth of young Rose.

He would sleep nights in the future with it wrapped around him, swearing it to be warmer than any three blankets combined and that he never knew coldness when it was upon him.

The day he left Stonehouses was late in winter, and Magnus Merian had already turned his attention to the coming season. But Caleum Merian was not to be there as they tilled the earth that year and planted their hopes on another spring.

The two men had just mended a hole in the fence of the western pasture together and returned home for dinner in the main house. They were all seated, and had complimented Adelia on the meal, as Libbie nursed young Rose, and Caleum carved the roast. It was as he doled out the food that they heard the sounding of the knocker on the front door. When the great clacker sounded again, they knew it could only be one person in all of Berkeley.

Caleum went and answered Stanton’s knock, and their neighbor entered the hall all in a flush. “We are sending a regiment up to join the Continental Army,” he said. “Naturally, I have volunteered the Berkeley militia to be among it.”

Looking at his face then, it was clear to all that what he was announcing had been a lifelong wish, which he kept secret until that moment. During the hours when he debated other men and seemed to take their opinions into consideration, it was just they themselves he considered, as his own opinion was etched already and he waited only for its soundness to become obvious to others. It was clear as well that all else in the world was present in his mind only to serve this one great purpose.

He could not stay for dinner, he said, having much else to do that night. He gave instructions to Caleum as to when the militia would assemble and depart, leaving him with his family until that time. Caleum went back to the table and delivered the news.

All in the hall were feverish with the excitement and uncertainties it induced. These they did not speak of aloud, because they did not want to burden Caleum with worry. Instead they tried to turn dinner that evening into a proper feast, eating and conversing until late at night and sparing nothing for Caleum’s pleasure.

He was happy for these comforts of home, as he dined with his wife and child and the uncle and aunt who had reared him as their own. In his mind, however, he was already preparing himself to live without them.

He did not wish for bloodshed, but he could barely wait for the next day, when he would leave with the army. His impatience was only partly due to confidence; the other part was the fact that one night while practicing with his sword he looked at the metal and saw there a picture of himself, which enveloped both sides of the blade. He stood with the weapon in a position of conquering, and all around him men fought in battle. He was larger than the rest and cut through a great many of his enemy.

He startled when he first saw this, having never noticed such an engraving on the sword before, but he knew, when he did, that this was perhaps his own great purpose and duty to fulfill. That he did not fail in his responsibility was a thing as meaningful to him as Stonehouses itself.

His life made sense to him then, as he mounted his favorite horse the next morning and flew to join the battle, and the morning sun lit up and reflected off of Stonehouses as he sped away.

IV. lamentations

one

He is strong as any man in the thirteen states and his arms have grown thick as oak boughs from wielding his sword to hold them. To see him you would think he was born to martial life and never did know the country fields or hearth of family. It is these he misses most, however, on his long war campaign, which has stretched far beyond what he or anyone else ever imagined when he first left home.

He knows now how seldom victory comes swiftly; that it is always hard-won and bloody. As he waits for the battle to be joined again at Saratoga, the farmland reminds him of his home, which was called Stonehouses, and he wants nothing more than to return to his family and take up his plow again. He will be moored permanent to his land then – instead of in brief respites such as he enjoyed winters during these three years of fighting – and no more leave it for any reason. Yet deep within himself, he knows there is also another possibility: that movement is in his blood now, and nothing can suppress what it has taught, and even homecoming will not alleviate it. It is the privation of having been apart from everything dear to him with no certainty of returning. Some knowledge, he thinks, is never lost, nor the cost of acquiring it forgotten. It has made his brow heavy and wise seeming, but it is sadness he feels when he stretches out for the night.

It is something other in the morning – a hotness – as he anticipates the next battle.

In the early months, when the colonists first faced the Great War Machine, they tried to match it gear for gear. However, they quickly found their enemy was all levers of warmongering and cogs of empire-making, and they were mowed down incessantly beneath it – or else humiliated by what they did not know. It was only when they learned to separate and attack individually that the spirit flowing between them had room to reveal itself, like a massive inevitable net, and they had any chance of winning.

As they sat around camp in early autumn, with the cooking fires aroar between them, the men took stock of their supplies and cleaned their equipment after the long days of silence, during which time the pastures of Saratoga had not known blood but only waiting. Lunch that noon was a thin soup provided by the farmer who hosted them on his land, augmented by a few wild hares some of the men had snared that morning. He sat under the cool October sun to share in the meager repast before the time when fighting would start up again. John Corbin, a freemason out of Burlington, who had fought so gallantly at Long Island and Brooklyn Heights, sat on his left. Herman Van Vecten, who had spent his twenty-fifth birthday in that camp and looked at least a decade older, was at his right. Carl Schuyler, who was commended for bravery at Trenton by their commander in chief, sat in front of him, slopping soup. There was also one called Ajax, a slave out of Maryland who had proved his worth at Brandywine. His other companions were a freedman called Mace, who took rather too much glee in the doings of battle, and a man called Polonius from Delaware, who had been promised his freedom for fighting and had surely won that already, snatching it from death again and again during the spring campaign just passed. The slave Julius, whom Caleum knew from youth, had also been enlisted by his master in the third year of the war, after he found out what the bounty was. For the fight he gave, though, one could not have paid enough, and the others soon forgot his status.

Among them all none ranked higher in the esteem of his compatriots than Caleum Merian himself, whose exploits were known through New England and the southern sphere alike. Even among those tempered and hardened soldiers, he was most skilled in killing.

As they ate their meal, a sentry came into camp and had words with the general in charge. When he left, the officers could all be seen gathering hastily in the center of camp for a war college. After a brief conference they sent out instructions among the men, who all knew by then that a fight was in the offing. They were ordered to ready themselves and form battle lines, as the British and Hessians were advancing toward their left flank in ambush even as they ate.

A panic spread through the newest recruits, who were fresh plucked from the farms of the country and still knew only what they had heard about the might and invincibility of England’s army.

Caleum and his fellows finished their own meal as if nothing unusual were afoot, took up packs and muskets, and assumed their positions in the column that was forming out in the open meadow. They were the center of the formation and its pillar, as they were the most seasoned and would be hardest to break.

When the bugle sounded they marched out toward the enemy line obdurate as Spartans, prepared either to die or seize victory from those fields of death.

At three o’clock that afternoon, they finally met the enemy across a distance of some fifty yards.

As the mountains rose and stretched in the distance like a great stone spine, the British and the Hessians raised their muskets at the patriots, taking slow and careful aim. A volley of thunder rang out then, deafening all around, as the report from fifteen hundred guns sounded a testimony of certain slaughter.

The unseasoned Americans scattered in every which direction when the volley sounded, as mounted officers tried to whip them back into formation. When the gun smoke cleared, only Caleum and his men were still standing in their original formation, with none yet wounded – and no one yet dead.

They raised the muskets on their side then, for the first countercharge of the morning, keeping their nerve and aim steady amidst the chaos. Each fired in unison, releasing their own noise to answer the enemy’s – a report of Continental will. The sulfur rose like steam as the British and Hessians fell from the lead that rained upon them.

What happened next, no one was prepared for, as it had happened so seldom before in history. The British line broke.

As the patriots rushed forth, it scattered here and yon without the collective discipline or thought that struck awe and terror in all who had gone against it, and the Continental Army began cutting them down in a frenzy as they fled. The farm boys, who had not seen battle before, grew over bold in this melee and rushed forth ahead of the rest of the line, looking for glory. They almost knew it, too, but were soon turned back on their heels, as the Englishmen regained the advantage and formed their line again.

The redcoats next gave chase with their bayonets drawn, having not time to reload their muskets as the Americans flew before them. The newer troops melted away again, like so much wax before a match, so the British met Caleum and his men instead, at the center of the American column. They too were without ready muskets, except Carl Schyuler, who could reload faster than any other man in their army. He fired on the advancing line, and one of the Hessian mercenaries fell onto a spot that was still green with grass.

The remainder of the center kept charging until the two lines crossed, point for point, and steel for steel. Instead of his bayonet, Caleum met them with his sword drawn, and he cut many men down that afternoon. One after another they fell under the steel’s swift working. As they died each felt a great heat when their spirits departed their bodies – even those whose destination was the cool rooms of Heaven. They felt the heat alike who had lived in right correctness and who had lived in profitable sin, for the sword was indiscriminate in this and knew only fore from aft, foe from author and master.

Not that the fight was all one-sided that day. The British and Germans eventually rallied again, pushing the Americans back and taking from their ranks such souls as they managed to reach with their own war metals. They claimed lives that day from Massachusetts to Georgia, reaping seasoned soldiers along with the farmers, who fought with more spirit than skill. They made widows of the wives of officers and infantrymen alike, tangling with all the ferocity they were renowned for.

The tide of battle reversed itself again only when General Arnold, who had been stalking his prey all morning, gave his marksman the order to fire and General Simon, his British adversary, fell from his mount in a heap of flesh. With their leader lost, Arnold led a charge into the British center, which gave way before him and began to withdraw.

Caleum gave chase with the others all the way to Berryman’s Redoubt, where Arnold was finally checked, nearly losing his life. The fighting continued, though, even without generals but with a will of its own. The soldiers kept falling on both sides all morning, but native love of native land was favored over Albion greatness by the end of that afternoon, and Fortune exchanged one for the other in her bosom.

Caleum pushed forth in the midst of this possessed of the spirit as the rest of them, but he stood a full head above the next tallest man on the battlefield and was almost as high as their standard, so when he let out a great bellow it seemed to proclaim the strength and intent of the entire army as it fought to stave off defeat.

He was magnificent that day, as he fought against the best Great Britain could muster. And when the redcoats heard his cry and saw the glint of his blade, even they were stirred with respect for their enemy. As darkness fell the fighting began to end at last, but for Caleum there was still one more contest in the day.

The Hessians had fallen back to their earthworks and were well dug in, firing cannon from inside that hailed down on the other army as a detachment defended the walls from without. Behind the line their commander of artillery, who had replaced his uniform of common wool with blue velvet and was dressed in it from head to foot, walked back and forth, making adjustments here and there to the cannon. After each walk down the line, he always returned to the center, where another figure, dressed all in red velvet, sat on a field stool, whispering advice to the commander from time to time, though they looked like two figures from Gin Lane. The man was their munitions expert, but Caleum recognized him immediately as Bastian Johnson, once of Berkeley.

He could not tell what the two men were discussing, but it was gravely serious, as it was only these guns that kept Caleum and the others from annihilating their side completely, and the cannon fire did not cease and was unerring in its accuracy.

As they drew up for one final assay before darkness drew its final veil, a figure lumbered out of the gray quarter light toward Caleum Merian. He alone of the men on the field that day was as tall as Caleum, and everyone in his path knew immediately who offered the fight. He was called Jupiter and came down originally from Mashpee. He had won his first fame on Bunker Hill, though it was a losing day for his side. He fought first for his freedom, as many men did during that campaign, and then he fought on for the love of it.

When Jupiter saw Caleum, each knew whom he was meant to face that day. And as they moved closer to striking, each was worthy. Both their hearts were enflamed with want to vanquish his rival, because each knew the other to be the strongest from his side, and each had it in him to test his mettle, steel against steel, not flint and ball from afar.

When they stood inside three yards, each drew his sword for killing. When they were nearly close enough to touch, their blades clashed in the air with a ringing that seemed as if it could be heard for miles around, as if the entire war had come down to only this battle between the two of them.

Unlike many who had faced him, Jupiter’s sword did not give way immediately but took the shock of Caleum’s blow when it struck his own. Nor was the man himself overwhelmed. He simply drew back and attacked again.

As they fought, Caleum felt for the first time he was fighting his only natural equal. In another time they might have been friends, and one side against all others, having some shared understanding. Here they were enemies. Each wielded his strength and skill for his cause and each fought superbly – as they came at each other again like Titans in the bitter mouth of chaos – and neither yielded from fear nor lack of stamina or tactic.

In contests of giants, though, there is never a deadlock but always the annihilation of the weaker ego, as fate lashes out with cruelty. In the course of seeking out advantage, one side must give so victory can progress, one over the other, no matter how tremendous a fight has been waged or the goodness in each warrior’s heart. So it was for the two of them.

Here it was Jupiter who first felt the heat of steel pierce his flesh, making his blood run purple then red into the dirt of Saratoga.

He grew enraged after that, as he started to drink from death’s cup just handed him. In a flight of madness he let go all caution and training to rush in toward Caleum’s blade, either to kill his opponent then and there or else speed the course of his own blood’s flowing.