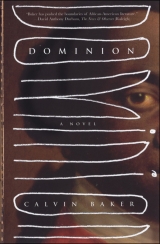

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

three

Nothing. When he returned to the inn there was no message for him from Mr. Miles, and none the following day either. As he sat in his room the third day, waiting for the man to contact him, he began to grow angry at the time it was taking. Whenever he heard someone on the stairs his breath would catch for a small expectant moment, until the footsteps inevitably passed by his door, like good fortune. No one came at all, and, as he knew no one in town other than casual acquaintances, the days seemed to stretch on with an endless bleakness.

The city beyond his windows was nothing but shadows when he looked out that evening near the close of shop hours, and the room itself was reflected back at him in the leaded glass. He could hear now and again the sound of travelers making their way home, but little else that had immediate meaning for him. He let his mind drift toward his own family, whom he was increasingly anxious to see. In this mood of longing he went to his closet, where he took his coat from its hanger to look once more at the scene on its inner lining that he had gazed at so often. To his surprise he found it had faded even further and looked crude to him. He had not noticed this wear before and peered at certain places where the stitching was frayed, attempting to make out already-lost details. What would they think when they saw him again? Had he faded as much from their memory’s care? he wondered, until the thought became suffocating.

He did not remember falling asleep, but when he awoke it was already well into night. He roused himself from bed to go for his evening meal, if one could still be had, but instead of leaving immediately he wanted first to put on a clean shirt, as had always been his custom before the war. He was surprised when he looked in the trunk to see he had none left, and was aware for the first time that all his clothing was in great disrepair. He was not a vain man, but he did not wish to give the wrong impression about himself either, such as might lead someone to mistake him for other than who he was and what his station was. He decided then to have his dinner that night in the hotel, and went down to the dining room tentatively on his crutches. Once there, he was pleased to find they were serving rack of lamb, his favorite dish, though he had never had it on any day outside of the Sabbath. It seemed a great decadence to him, but one he was happy to indulge.

As he ate, he felt his earlier sense of contentment return, drawing a satisfaction from his stomach that seemed otherwise to elude him. When he finished his meal he took out his new pipe and began smoking. He did not, however, enjoy the pipe as he had before and was about to extinguish it when the proprietor’s boy came over to the table with a small pouch.

“My father said to offer this to you. It’s hard to get decent tobacco in the city now.”

When Caleum filled his pipe with the proprietor’s offering he could scarcely believe the difference between the new tobacco and the smoke he had purchased earlier, even though it had cost him dearly. He had thought when he first tried it that it was simply a vile custom, but this new tobacco made clear to him the pleasure of the habit. He luxuriated in the rich aroma of smoke and ordered another cordial, for the boy came round to check on him with an attentiveness he had not observed anywhere else. He thought then there was nothing unavailable to a man in that town and delighted in the satisfactions of the table.

After finishing the cordial and pipe, he went upstairs, well contented with both himself and the city and beginning to feel rejuvenated. When he lay down that night he fell directly asleep and enjoyed a deep restful slumber.

The next morning he rose early and went down to the dining room, where instead of porridge, which had been his usual breakfast for as long as he could remember, he had a plate of eggs with bacon and sausage, thinking he might as well enjoy himself fully while he was able, such leisure being unavailable to him ever before, and it coming after such sacrifice. When he finished his meal, he asked at the front desk where he might find a good tailor, as his clothes were in a state such as he could no longer bear.

The proprietor was quick with a suggestion and pointed out the way to get there from the hotel. As he walked up Broadway through all the bustle of the business day, Caleum felt as if he were on holiday instead of merely performing much-needed chores, and this in turn livened his mood. When he arrived at the tailor he chose the fabrics he liked best, then instructed the man to make him four complete suits of clothes and ten good shirts, as he was unlikely ever to be in the city again.

When the tailor asked whether he would also require a new greatcoat, Caleum thought it over for a very long time before answering in the affirmative. His old coat was much worn, and it had besides been a coat meant for war, not civilized life, and he was now again a gentleman of peace. He paid out his gold and asked where he might find a good barber.

“The best Negro barber in the city is said to be John Paige, up by the Collect,” the tailor answered promptly, writing down the address. Caleum thanked him and left.

It was still before midday when he reached the street again. He thought about hiring a coach but decided on walking, as he had grown quite used to his crutches, so much so that he had begun to move about on his three legs as well as other men on two. He went up Broadway lightly, until he came to Chambers Street, where the bare trees lining the road allowed the sunshine to fall unimpeded across the wide sidewalk. It was a bright if brisk day, and the warm light felt good to his skin as he turned east toward his destination.

He was immediately overcome by an unbearable stench, though, and saw that he had entered a precinct of tanneries. The odor of animal skins and lye strangled the air, as dirty reddish water ran over the sidewalk and into the gutters. Here and there, he could see large clay vats filled with different-colored dyes, all very rich, and skins stretched out for drying. Bits of hair, or wool tumbled down the street, which he was careful to step around, not wanting to trick his balance.

When he finally passed those stinking streets he was in a small lane filled with breweries. He was reminded then of the serving girl who had brought him his lunch the day before. Perhaps he would eat there again, he thought, looking down to check the address of the barber on a slip of paper the tailor had given him. When at last he found the place he also found himself weary, having walked farther than he had reckoned on its being, and searched out a place to sit down. All the clients inside the little shop were Negroes such as himself, but of every caste of life, from the African who spoke but little English to the stern faces that seemed to him more Dutch than Negro. Still, he was comfortable, as he was in a good mood in general, and reclined amiably in his seat.

When he finally sat in the barber’s chair, he requested a full shave and haircut. The barber was a tall dark man who looked gruff, but when he began working he was very ginger and methodical. It soothed Caleum to feel so well cared for, which he could not remember being since he was a boy, and the shave was the best he could remember. When it was done he looked as though he had shed five years off his age, and he left the chair feeling like his better self again. More than that: He felt he had shed a carapace that had grown up around him in place of his normal skin.

He set about then to find the pub from the day before. He walked back the way he came, past the breweries and through the tannery district, at which point he was too tired to continue and decided to hire a coach.

By the time he found the pub the lunch crowd had all left, and the room was nearly empty. The same waitress who had attended him before was working again, though, and when she came to show him to his table there was the same enticing openness about her.

“You’re a bit late, aren’t you?” she asked, as if their meeting had been previously arranged.

He did not answer, not knowing how one was supposed to deal with such directness. He wondered whether she would take offense if he were to give his own tongue such free rein. He had not made an advance toward a woman in that way since his marriage to Libbie, and then it was according to the rules of proper engagement, while here in this city he could not tell what rules governed the different interactions between the sexes.

“I see you’ve had a haircut?” she went on, not seeming to mind that her last question had gone unanswered.

“I did,” he answered, taking the same seat he had previously occupied.

“Well, it looks very smart,” she continued.

“Thank you,” he told her. “What do they call you?”

“Elissa,” she answered him. “And who might you be?”

“Caleum Merian.” He introduced himself with both his names, even though that did not seem always to be the custom of the island.

“Well, it is very nice to see you again, Mr. Merian,” she replied. “I think the chowder is good today.”

He simply nodded, allowing the woman to chose his meal for him. When she brought it around, she had the same smile as before, which prompted him to wonder again how she would respond if he made an advance. Emboldened by the fact that he had no reputation in that city, he decided he would do just that when she next came by the table.

“Would you care to meet me this weekend?” he asked, when he saw his opportunity.

“And just where is it you want me to meet you?”

“At Bowling Green,” he answered, trying to think of a place that would not seem too intimate.

“It’ll be freezing there,” she said. “But I’ll be at Mary Hamlet’s on Saturday, around eight, if you should happen by.” She smiled at him again.

“Where is that?” he asked.

“You’re not from here?” she teased him. “It’s over on Mulberry. Everyone knows it if you have any trouble.”

It wasn’t until he left that he realized the implication of what he had just done, and it occurred to him that he knew nothing about the woman. He worried he had made a bad decision and told himself he was not bound to go there, as she knew little about him and would never find him again if he chose not to go. As he remembered her smile, though, he knew he would venture to meet her. There was something about her he found exhilarating in a way he could not remember having encountered before, and he allowed himself to trust this instinct.

He remained hesitant, though, as he was very strict with himself in such matters. What he argued then was that it was only lack of feminine company for so long that made him feel as he did. The line of thought turned on him, however, and he found himself arguing that this was a perfectly good reason why he should enjoy her company the coming weekend. He told himself to let his boldness have its way and see how far it would get him. Despite his efforts to quell it, he found this inner arguing and turmoil delicious in and of itself, both as its own pleasure and as an intimation of larger ones to come.

He reached the inn with the same lightness he had felt the day before, knowing he would accept her invitation, from curiosity if not the growing loneliness he felt there in those days.

He hoisted himself up the few stairs that led to the door and entered the hotel, hoping his new suits might be ready before the weekend. As he continued on to his room, he heard his name called. He was delighted indeed when he turned around to see Mr. Miles waiting.

“Mr. Miles,” he said, greeting the other man. “Have you been here long?”

“No, sir,” Mr. Miles answered. “Only just ahead of you. I have your order ready, and have brought it around so you can try it for fit.” Caleum nodded, and indicated that Mr. Miles should follow him up to his room. When he closed the door, Mr. Miles opened the large box he was carrying and removed from it the most beautiful piece of wood Caleum had ever beheld.

He peered at it a long while, then stretched out his hand and let his fingers touch the new limb, and it looked exactly like a leg, so much so that but for its texture and shading he would be hard pressed to tell it from his other. It felt cold and ungiving, such that no one would ever mistake it for the living thing, but it was no less accomplished because of that and even seemed alive in its way.

“Do you wish to try it?”

He nodded, and Mr. Miles approached and began explaining the fastening mechanism he had crafted, so that the binding of wood and flesh would be absolute and dependable.

“It takes a bit getting used to,” he went on, as Caleum sat down and allowed the man to affix the wood to his gnarled stump with greater care than any doctor he ever encountered. When he stood, Mr. Miles handed to him a cane made of the same wood as the leg, and it was just as well-fashioned and polished.

“You might want to keep with the crutches for a while, but in time this will give you a little better mobility,” he explained, while Caleum walked from one end of the room to the other.

“I have seldom seen such craftsmanship, Mr. Miles,” he told the other man, moved to joy by what he had made. “It is not so heavy as it seemed in the box and feels very strong.”

“Aye, your coins are the same mint, but for this, Mr. Merian, even steel could not cut it.”

“Aye, Mr. Miles, I knew the blade that could,” Caleum said, casting his eyes at his visitor, who then looked at the still living stump of Caleum’s leg above the wood, before averting his gaze.

Caleum went back and forth across the room several more times, growing used to the new appendage, until he thought he could feel not only the impact of the wood with the floor, but that he also sensed when anything was near the wood as well, even though he knew this to be an impossibility. When he was satisfied, he sat down.

“Thank you for such a fine job, Mr. Miles,” he said.

“I tried to give it my best, sir,” the man answered. “If you need anything else at all, please don’t hesitate to send for me at my workshop.”

With that he stood and began to withdraw. Caleum lifted himself again to see his visitor to the door. When the other man had gone, he went back and forth across the room again, before putting on his old coat and going out to try his new leg in the street.

Once he exited the hotel, however, he felt an immediate self-consciousness. To see a man without a leg did not seem so strange, but to see one upon a wooden leg he worried would be odd. Nevertheless, he began walking toward Bowling Green with as much confidence as he could muster, trusting this new leg beneath him would be faithful.

By the time he reached the great lawn he could feel the weight of the wood and found himself tired from carrying this new burden. He found a bench to rest upon and sat there, looking out toward the Sound as the autumn wind blew north. As he watched the sails moving out in the harbor, through the barren branches, he wondered which of these vessels might take him home if he went down to the dock at that moment to book passage. If he went that very day he might even make it in time for Rose’s birthday.

He knew, though, he would not go that day. He needed at least another week to finish his business there, and to recuperate, before taking up the burden of travel again, to say nothing of husbandry.

He thought again about the shock it would be for them at home, when they saw him, and wondered how he would be able to fit into his former life again. Although every year he had seen those conscripted go from being farmers to soldiers and others going back again the other way, he did not see how it could be so simple a movement and knew the first one was easier than the other. It takes awhile to relearn one’s former self, he thought to himself, as he looked toward the ocean, if ever it is possible again.

He wrapped his arms around his shoulders, pressing the embroidery inside his coat against his body. I will make it there in time for Thanksgiving, he promised himself, and he was satisfied as evening fell and he walked back to the inn for supper.

four

He arrived at the hall, on a narrow, slanting street off the main way, promptly at eight o’clock, only to find it still deserted. He went to the bar and ordered a glass of rum, which he took to a table off on one side of the room and sat alone, nursing it. By nine o’clock the hall had grown half full with people, but he still did not see Elissa. He told himself it had been the remotest of possibilities to begin with, and that she had never promised him her company. Perhaps she had been teasing, and it was only her way. He tried to decide then whether he should leave to find other amusement or stay on in any case, to see what else might unfold there that night. He felt foolish, though, and had decided to leave when he saw two faces appear at the entrance whom he recognized from his past.

The first to enter was Carl Schuyler, from the army, and just behind him was the slave Julius from Berkeley. When they saw him they immediately came over to his table, and he stood up to shake each of their hands, glad to be reacquainted and, beyond that, elated to see familiar faces.

Julius, who had known him longer, was first to speak. “The last time I saw you, they was leading you from the battlefield, and we all thought for sure you’d died.”

“I did not,” Caleum answered, signaling to the waiter for more drinks. “But I came powerful close. Has your own tour ended?” he asked next, changing the subject from his own fortunes.

“No, but the fighting has stopped for the winter, so we were given a leave.”

“We can travel on to Berkeley together, then,” Caleum said to Julius. “It is good to have company on the road.”

“Any other time I would, but I’m not headed back that way.”

“That’s where your sister Claudia and the rest of your people are,” Caleum said. “They’ll want to see you.”

“Unless I want to be always and ever somebody’s slave,” Julius answered, “there is no place for me there anymore.”

Caleum could only nod at this. “Where will you go instead?”

“I don’t know yet, but not back to bondage,” he said defiantly. “Not under my own power, at least.”

“Then we must make the most of our meeting,” Caleum proclaimed. He had never been one for rich meals and lavish wines, but he ordered as well as they could from the menu offered in the hall that night. Their table was laid with the best fruits of the harvest, and the choicest meats, and they dined sumptuously, reminiscing and telling feats of past bravery and wishing one another only good fortune for the future, especially for Julius in his new plans.

He had all but forgotten how he originally learned of that place called Mary’s Hamlet – and was lost completely in nostalgia and boasts with his old acquaintances – when he saw Elissa standing at the end of their table. He offered her a seat among them but did not stand.

“I’ve come with friends,” she answered, but his own friends were well supplied with drink by then and eager to have women’s company. They told her there was more than room enough for all of them at their table.

When the places were filled, and everyone had been introduced, the laughter and fellow feeling reminded Caleum of those festive days as a boy when his grandfather entertained in the great hall at Stonehouses. Although he was not among kin, he felt as cheerful as he had then, enjoying the pleasures of sharing his board with friends.

Elissa sat at his side, and each time she laughed she leaned toward him and brushed lightly against his arm. It had been years since he felt a woman so close, and each time she touched against him he wondered what it meant, but also why he had held himself so chastely and apart from feminine company. He thought then of his family and children. And was reminded in general of all those things the heart will not relinquish. Julius and Carl were both surprised to see him so casual that night, as he was always rigid with dutifulness since each had known him. Now he relaxed, letting the evening expand unchecked and allowing whatever suggestions it might make to hold and seduce him.

He watched the girl Elissa as she interacted with his friends, and, though some might think her beneath the women he was accustomed to, especially Libbie, she had a way of making those around her feel relaxed, as all mingled freely according to whim and will and not as was dictated by usual social customs. Caleum also held Julius in the light of friendship again, as he had not done since they were boys and all equal.

“Did you notice anything strange at Saratoga?” he asked, taking Julius by the shoulder, when they had exhausted their talk of battle and everyone they both knew from Berkeley.

“Everything was strange at Saratoga, and all of it too familiar.”

“Did you see anyone you knew from other days?”

Julius nodded in recognition. “You saw him too?”

They both shuddered with sadness. “To see him there, you would think he had never known any other life,” Caleum remarked.

“I’m afraid he doesn’t know any life at all anymore,” Julius said, going on to report how Bastian had been mortally injured at that battle, as he oversaw the artillery with his lord. “When he was shot, the Blue Colonel was on the other side of the field, and they say he would not let anyone else touch him, calling them all commoners who tried.”

“How far some men seem to travel from their origins,” said one of the ladies, who was deeply affected by the story of Bastian Johnson, when Julius had finished relating it.

“Aye,” they all uttered at different volumes, then paused to lift their glasses in a toast of remembrance. As Elissa placed her glass back on the table she touched Caleum’s arm again, and in that moment he felt a doorway back from the isolation that had gripped him for so long.

It is not good always to eat alone, he thought, placing his hand upon hers, very briefly, without looking at her.

“Would you like to dance?” Julius asked the woman next to him, who was called Sally, as the table grew quiet. She took his hand gladly, and they stood to make their way to the ballroom floor.

“Let’s all dance,” Carl suggested, at which everyone at the table stood up eagerly except Caleum and Elissa.

They all looked to him, to make certain he was not offended, but Caleum only looked back, then pushed his chair from the table slowly and stood to his full height. He held his cane in one hand and offered the other to Elissa. She took hold of it and followed him to the dance floor, smiling but nervous for his safety.

In the middle of the room, Caleum placed one arm around Elissa’s waist and held her hand with the other, grasping his cane simultaneously in case he should lose his balance.

He did not, and when they moved over the floor it was as if wood had great respect for wood, and while he was not perfect in his movements, he was more graceful than any would have expected. They danced through two songs and made their way back to the table only when he was well tired out.

After they sat down the waiter brought over another bottle of cordial, and the two lounged in comfortable weariness. They were easy with each other then, as they had not been earlier in the night, and spoke tenderly in whispers as the rest of the room went about its affairs.

Eventually the others returned to the table as well, but by then the rest of the crowd was thinning and it was time for all to go home, or wherever they were passing the night. Caleum made arrangements to meet with Julius and Carl later in the week, when they announced their departure, but he and Elissa stayed on in the hall, reclining and talking softly. At last the music ended and they could stay there no longer, so walked out into the freezing night air together.

Under the white light of the gas lamps Caleum was bold indeed when he invited her to return with him to his room, but she declined, saying it would not do. There was, however, another inn, known as a place where lovers carried on surreptitious affairs in secret warrens, and he assented to this and let her lead him there through the frigid streets, until at last they reached the place and climbed the stairs and could be alone – as they were anxious to be.

They were still ensconced there two weeks later on Thanksgiving Day. Despite Elissa’s desire to cook for him from her own pots and serve him off her own table, they could not go where she lived, for fear of scorn and disapproval. Instead, Caleum took her to an inn he had heard of, which had the reputation of serving the best food in the city.

Julius and Carl had both left the island already, Carl to visit with his family in Boston and Julius to see a woman he had met at Mary’s Hamlet from New Jersey, but Caleum had only moved from one hotel to another, being enchanted by Elissa as their affections for each other seemed to grow and grow. He would not – and perhaps it was only guilt that held him from it – term what passed between them love, but it was a rapturous thing all the same and he thought it a worthy rival to domestic contentment, though whether it could last he dare not ask himself.

At the inn they were seated at a good table by the owner, and all through the room were elegantly dressed men and women, many with children, enjoying themselves as the waiters brought a sumptuous feast to every table. When their own table was laid, Caleum gave prayer and named all his thankfulness for that year.

Elissa testified after him, and, although she had been made nervous when he mentioned his children, she told first how glad she was for the gift of his affection – claiming to have never known any before it.

They feasted then on a meal that made clear how the place had earned its good name. Such fine food, such good drink, such merry company – however, all that could not stop Caleum from wondering to himself what was happening that day at Stonehouses. If he had been wearing his old army coat he might have gazed at its interior scene then, but that garment was on the bottom of his trunk, and he wore his new clothes, which neither comforted nor burdened him with any memories.

As she watched him, Elissa began to grow cross and asked where his thoughts were. She was in a hard position, and knew she could not make too many demands on him or even ask him to stay on beyond what he wanted, even if it was her deepest wish. She was relieved therefore when he answered her duplicitously – claiming only to be thinking of old acquaintances – satisfied that he did not say outright he was thinking of his family or else that he wished he had left already to be with them.

“This is the best Thanksgiving I have ever known,” she said, touching him on the arm and holding him fast.

“It is one of my best,” he said truthfully, thinking first on that list was the year he was first blessed with Rose.

Their joy with each other had not traveled its full course, but Elissa was afraid then it was running out, and throughout the meal she kept asking her lover for reassurances. This in turn soured Caleum’s mood, as he felt he was being pinned down.

“Let us have another cordial,” he said, “and enjoy our meal. I am as happy as I have ever been here. You must not worry so much about me leaving you.” She was serene when she heard his words, secure for the moment that his heart and devotion were with her.

Nor was what he said merely a deceit to put her off pestering him with questions. He was as happy with her that day as he could remember. It was merely a different sort of happiness than what he was used to, and the knowledge that pleasure itself could be pursued in the same way he had gone after his wife, or his yearly production, was a small unsettling revelation to him. He had thought before that stable marital harmony was the only dependable kind there was, but now he knew it was only one of many and not better than those others, merely a different formulation. It dizzied him to think of it, as he saw how arbitrary one way of life might be over another.

When he first found himself thinking this he feared it was devil’s logic; however, he did not know how to resist it, for he could find nothing sound on the other side that satisfied the question of why one form of life was better than another, or even why going after what was strenuous and correct was better than going after what delivered the greatest joy.

He knew men learned in religion would reproach him sharply and make clear with moral reasoning what was unavailable to his intellect alone – but that he loved a woman who was not his wife, even the most pious of them could not argue away, or tell him why he should not believe in its existence.

His heart then had its own method of philosophizing and reckoning, which did not square with the others at all, asking his conscious mind whether, if a man’s sin is that he is not an angel, might he still not be a worthy man.

“Will we spend Christmas together?” Elissa asked him in the midst of all this, for she was equally in love with him and saw in his eyes that she had gained ascendancy in his mind.

“Yes,” he answered her, smiling. “We will.”

She was made happy by this, but for her position to be truly impregnable she knew there was only one way to achieve that goal. For a woman she could compete with, no matter how fancy she was, but his children would always tug on his bosom, unless he had others with her. It was not a cold calculation on her part, only a reasonable one, as matters of the heart often need aids of reason to sort out their arcs and realize themselves.

When they finished with dinner, she was especially affectionate with her man and, rather than seek out other amusement for the evening, insisted that they go back to their little hotel, where they might pass the rest of the evening together in bliss.

That night as they lay again in their secret chamber, she thought how the spell of love alone could not last indefinitely, and asked him again to tell her his love for her. He answered with sweet words and knew there was much truth to them.