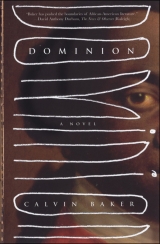

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

eight

A train of princely coaches thundered over the road the first passable day of spring that year. A herald out front proclaimed its origin, and the king’s standard flew high overhead, guarding it against inhospitable actions. Its presence so far out was a confounding mystery to Merian and Sanne, and it was continuing on even farther – to an outpost that had cropped up more than two days’ journey from them, for it was a long time since they were the final dwelling on the road.

The mystery of the coach remained unsolved until Merian’s provisioning trip a few weeks later, when he stopped for his usual draught, and Content mentioned the self-important travelers who had stayed over at the inn about three weeks earlier.

“Who were they?” Merian asked. “What was their business?”

“I guess you didn’t hear”—Content nodded, offering him another pint—“but we’re going to be a colony of our own.”

“Don’t you think Dorthea and Sanne might be a little upset by that?”

“It’s no jest,” Content countered. “The colony is dividing in two.”

“On what grounds?” Merian asked, though he didn’t see how it could make a difference to them out there, whatever the case.

“Rulers and ruled upon. Anglicans and Presbyterians. Plantation and freeholder. Crown and colony,” a man sitting in shadow at the end of the bar interjected. “Past and future. However you want to square it. There’s not a whole lot of grounds where things aim to stay the same.”

“That’s all dukes’ and governors’ business,” Content said. “It won’t matter any to us out here.”

“You are an optimist, my friend,” the man at the bar argued, standing and coming over to join the other two, “as well you should be, all the way out here with no arrow in yer skull. But it will have everything to do with what goes on. Mark that, both of ye.” The stranger looked intently between them, and when he said, “Mark that,” Merian recognized his costume as one and the same with the fellow whose carriage he had fixed out on the empty road a few years past.

“You’re one of those wandering preachers, aren’t you?” Merian asked him. “One of your kind passed this way before.”

“I am no such thing,” the man answered. “If I were, though, I would tell you great fortune has smiled on both of ye in the sundering of these lands. The other side is no place even for a dog, or else a king’s created harlot.” With that he downed his drink and stood to depart. “They want inventory of things that should not be in their cupboards to count,” he said. “Give them those stores and you’ll not run a free house anymore than you will the Holy Roman Empire.”

When he had gone, Content went to collect the monies left on the bar and held up a silver coin of the same marking that Merian had seen once before. The two then drank silently for a spell, wondering whether there was anything in the preacher’s forecast to concern them.

They decided in the end there was nothing for them to do about it and switched the conversation over to local gossip and general speculation about the future. Merian arrived home that night in a good mood, although there was nothing to account for it other than a feeling of being near to great events, even if those unfolded happenings concerned more the great landowners and estates of religion and did not weigh on him directly.

“There are going to be two colonies from here on,” he told Sanne. “One for the religious planters and another for everybody else.”

“I don’t see what religion has to do with it,” she asserted, as always on guard against his blasphemies. “In any case, they’re both for the big planters.”

“Well, one of them wants everything for Crown and landed, and the other claims looser confederation.”

“Will you still be able to go between them or will you need special permission?”

“They’re both still the king’s lands,” her husband answered. “I imagine for somebody with the idea, it will be just like going from here to Virginia or from there to London.” As he finished his sentence Merian grew suddenly less jocular, and he stood up to go out-of-doors where he could walk a spell by himself.

Outside the sky teemed low with stars and he charted the figures as he had known them in his childhood, trying to remember their names as he learned them then. He found, however, that he could not name them all as he used to and eventually went back indoors still burning with thought.

Sanne, after seeing him seized by one of his unpredictable moods, tried to ignore it, and when he reentered the house he found her already closing everything down for the night. He helped silently, then got into bed alongside her, where he attempted to mask his earlier moodiness with talk of how good the harvest was going to be again this year, if the weather should hold.

It was a mask but a true one; his yield from the ground had improved steadily as he invested it with fertilizers and good care each year, so that he expected nearly twice again what he achieved the year before. All the result of steady work and getting to keep his benefits for himself. This season, he reckoned, when his accounts were settled, he would leave with more ready cash than he had ever seen in his life, and no debt to any man.

When the harvest came he took his produce to market and received payment, more than a little amazed at the amount – for it was a sum that would have been unthinkable to him only recently.

He splurged then at the merchants’ shops and even spent a few pence at his sworn enemy the chandler’s, after seeing a handkerchief in the window he thought Sanne might fancy.

When he went home that evening he was loaded down with the winter goods in a new cart, which was pulled by the gelding he had bought to replace Ruth Potter, though he considered that particular creature irreplaceable and without peer in all the annals of animal husbandry.

He arrived back at Stonehouses at nightfall, and Sanne came out to help him unpack the cart and put things away in their cellar. He was proud then that, while before he had barely been able to fill a single basement with his labors from the season, this year two storerooms were scarcely enough to hold all his goods. He celebrated with a little of the bought whiskey he had picked up in his splurging, then presented his wife with her gift.

“Oh, it’s just foolish,” she protested, as she looked at the spun lace cloth. “What do I need with such a thing around here?” She could not, however, disguise her merriment at being presented with something so precious, or, for that matter, at receiving anything besides another pair of sturdy boots.

Nor was it his only gift to her. As he unpacked the crates there were all kinds of sweets and delicacies, such as had barely been available for sale in the place before but which were now well within their means. He drank in celebration of his growing wealth as well as the commerce that made it possible. He had amassed a sum of capital that was tremendous to his mind, and he knew exactly what it was worth and what purpose to put it to.

“I have another family I left back in Virginia,” he said to Sanne that night, as they lay in bed.

“What do you mean another family?” she asked, even as she had always suspected he kept secrets from her. “You have another wife?”

“Not legal like you and me, at least, but yes, you can say another wife.”

When she heard this she began to cry and berate him. “I always knew you hid things from me,” she said, sobbing. “What else is there? Do you have other children? Why, I bet you have them all the way up to Massachusetts!”

“Just one, Sanne,” he answered. “I had to leave both of them when they changed the law about where freed men could settle. I never made it a secret that’s how I ended up here. Or did you think I had lived all that time before you just by myself?”

“You never told me about another family,” she said, still tearing.

“That’s because I couldn’t do anything about it,” he answered. “I can now and intend to.”

“Intend to what?” she asked, sitting up. “What are you going to do?”

“Buy them out,” he answered her. “It don’t affect you and me, but it is what I promised them and still intend.” It had been his heart’s truth for longer than he could bear, although when he made the promise it had seemed like an earthly impossibility.

“You can’t bring another woman here; I won’t stand for that!” Sanne screamed at him. “I don’t care what you promised. If you try to bring your slave woman here you’ll both pay in hell.”

Merian chewed the inside of his mouth and said nothing else. He tried eventually to embosom and comfort his wife, whom he did love, until she could sleep. But in his pocket that money from the harvest lit him with singular purpose.

He rises the next day, before the sun has gained the rim of the horizon, while his wife still sleeps soundly, and saddles the gelding. Sanne wakes and listens to him outside, leaving, but does not stir from their shared mattress. By the time she realizes to herself where he has gone the sun will be at noonday and he will be unredeemable to her except by his own will.

He stopped for lunch at his customary time and ate in the saddle, to save an hour before taking back to the road again. The last time he was on this path he had been pressed to it by the legal inability to earn a wage and the misery that ensued. Still, he did not consider this ride back triumphant, for he did not know what to expect. He only knew he was in better condition than before – when he was beyond whipped and defeated and damn near dead. He tried not to think about it any longer or ever again, but if he did speculate in isolated moments he surely did not dwell on it, and certainly not on the last night before his manumission was a legal fact. Ebsen, the overseer, had visited him then at the party they were having in one of the cabins and, unprovoked, smashed him full in the mouth with a leather-wrapped fist.

Everyone in the room stared between the two, waiting for a response as the blood welled in Merian’s lip and Ruth clutched their boy toward her bosom.

Merian looked at the other man quizzically, determined not to be hedged. “I thought you and me were friends, Ebsen,” he said. “We never had discord before.”

“Well, we got it now,” Ebsen answered, smacking him again with his sheathed fist. “You think you’re better than everybody else here.”

The other men in the room made a cordon of bodies around the two combatants, though they knew it would take much more provocation for Merian to box.

“I’m not better than anybody,” Merian said, as the other man drew up to strike him again. “But I’m no less than anybody either.”

Ebsen beat his mute hand against Merian again, as if he wanted to teach him a lesson, though he himself did not know what lesson that was. He knew only that the other man’s lot had changed and his own had not; not for six years had it changed at all. He beat him in accordance with no known law but only because men do not like to know defeat, and he felt, with Merian’s advancement, something was lost to him, so tortured whatever he might to rectify that feeling.

He struck him again and Merian withstood the blows with his hands raised in defense and an equanimity that bordered on indulgence.

I bet he won’t try to hit me again, Merian thought now, as he drew himself up in the saddle and spurred the horse. I bet won’t nobody ever lay another living finger on me. The memory, though, of what had passed before filled him with a shame he could not speak. I hope Ebsen is the first person I see when I get to Sorel’s Hundred.

He rode for three days, barely stopping to sleep, as he stoked in his imagination the narrative of how the journey would play out and all the flattering variations of his original imagining. They were almost as fanciful as those of his last night on the old place, when he dreamed himself larger than his natural size, which was very mighty, striding a great mountain and holding a balled gavel in his hand. To the east the skies parted and he saw an antelope’s head rear and stare after him, as if to give chase. He responded by running, still clutching the gavel, until the eyes of the animal bore into him with such intensity he felt himself beginning to melt. To escape he flung the hammer directly at the stars and the sky, and only then saw that it was fashioned of horn, as it split in two along an enormous chasm that began to fill immediately with a great inrush of water, the eastern half receding, as if falling into the abyss of a well, and the western sky pushing up toward him slowly as if he were sinking to the bottom of a river. He woke before he touched bottom and reached out to Ruth. He knew there were those who could interpret it rightly, but he had never revealed this vision for fear, even while waking, of what it might mean.

A mile from the main gate he stopped the horse and went into the bushes, where he changed into a new set of clothes, like war paint or a lover’s talisman, which he hoped would render him stronger to stand and face the combined forces of time’s elapse before proceeding. He sat high in the saddle, marking the things he knew from those he did not recognize as he headed to the stable. In front of the red brick building, a crowd of children formed around him, all from curiosity but none in recognition. He dismounted and walked the horse to a fence post, stopping to shine a small one without hair on top of the head, and asked if they knew whether Ruth was round back.

The children giggled at him and ran off as he went on ahead, back to one of the old cabins, where he paused at the door to remove his hat before knocking on the weathered gray wood – as he realized that to let himself in was no longer his right. When he lowered his hand he heard movement from inside, causing him to hold his breath as the wooden slats gave way, and he laid eyes upon Ruth for the first time in over five years.

When she looked up and saw him standing in the doorway, he could plainly see she did not immediately trust it was him, as she looked on him as you might a phantom, or else something half-dream in origin. When he called her name, though, she responded by coming nearer, and they were both torn by a series of complex emotions as he entered the room.

He had built this structure himself, even if it was long ago, and though he could barely remember its bricks and beams when he entered, he knew its deep inner blueprint as he did his own hands and hide.

Ruth pointed out a low bench next to the table for him to sit at and asked evenly – as though his presence made sense to her—“What brings you this way?” There was such determination and so little revealed in her voice that it pointed to a knot of the spirit cord that held her and would not unravel even for this man who was once hers and stood here again after more than half a decade away.

“Ah, Ruth,” Merian said, standing and moving toward her, “is that the only welcome you got for me?”

“More than I had from you all these years,” she rebuked him. “You got nerve, man. I will give you that.”

He tried to explain to her that he could not just pick up and travel when he wanted, then began to tell how he had been hounded but found respite in Carolina. He stopped and settled on saying simply that everything got beyond him.

“Yes, it is,” she said. “Even if all you telling me is true, I know. …” Her voice trailed and her mind lit on to something that had been stoking there ever since he started talking. “Who is she?”

She halted as soon as the words tumbled from her mouth, when she sensed her betrayal and anger were revealed for him to appraise, and she didn’t want to give him anything more in that moment.

Merian did not answer for a while. He had not thought jealously of her in years, but her accusation planted its own counterweight in his mind, which pressed upon him. “What about you?” he asked.

And even after she had replied in the negative, “No one,” he would not believe it, because the curve of desire he found to be permanent and sturdy as lignum vitae.

“Stay and see who else comes here then,” she said, but he still would not let it go.

Just like that they found themselves embroiled in domesticity again. While the pair sat staring each other down, the door flew open and a child burst in, running to clutch Ruth around her legs. “Mama!” he screamed with delight, as if having waited for her all day.

“What are you running from?” she asked sternly.

“Nothing,” he swore.

“Hm,” she said, unbelieving. “Look who’s here,” Ruth instructed then, turning him toward his father. “Look who came all this way just to see you.”

It was a leap of faith that the boy made when he ventured—“Papa?”—waiting anxiously after that as his voice passed through the room.

Merian picked the boy up and hugged him. “That’s right,” he said, holding the child in his arms. “That’s right, Ware. Your papa has come to fetch you.” He looked over the boy’s head at Ruth as he spoke.

Ruth turned away to the cooking fire. “Don’t fill him with fool’s talk,” she reprimanded coldly.

“Here you go, Ware.”

Jasper gave the boy a hard candy he had thought to bring and put him back down on the floor.

“I mean it.” He turned to Ruth. “I promised it when I left here, and I came back to do it.”

“Magnus, go outside for a little while.” She shooed the child, calling him by his other name. The boy left grudgingly and went to sit in the dirt in front of the cabin as the two of them began at it again inside.

“What are we going to do, go back and live with you and your new woman?” Ruth asked indignantly.

As they argued there vigorously, someone knocked at the door, and Ruth opened it to a small crowd gathered out front of the cabin. “We heard Jasper come back,” one of the men asked. “Is he really?”

“There he is.” Ruth opened the door the rest of the way to show Merian, still seated on the low bench by the table. He rose as he looked out on all those faces he had not seen for so long, which filled him with a warmth of familiarity he had lived in the wilderness without. This is who he belonged to, he thought.

What his wife would not give to him by way of praise the neighbors did, telling him how well he looked.

A simple feast was produced then, with everybody contributing something, and he ate thankfully, thinking how long it had been since he had eaten the foods of his youth. He sat with the boy balanced on his knee. The child devoured glass after glass of milk, which had been brought out for the whole room, and pressed hard against his father’s chest. He was enthralled and said excitedly, to anyone who would listen, “My papa came back for me and Mama.” Those close enough to hear smiled at him with warm uncertainty.

Ruth commanded the boy to be quiet, shooting Merian an accusatory look. Merian for his part lifted his hand to his mouth and filled it again with food, as a couple of men began singing a bawdy song he loved and the party spilled over into the night. It is what he promised and intended, he told her beneath the din.

When the neighbors had gone Ruth took up their argument again. “I told you not to go filling his head with all of that.”

Merian did not want to argue with her, but neither would he be deterred. “You’ll set up somewhere near me,” he said. “It will work out fine.”

Ruth told him in her turn that she was going nowhere with him, even as he went on, trying to inveigle his way into their old bed. “Don’t be so stubborn,” he said at last. “You know, you’re so stubborn, woman, I named a mule after you.”

“No you didn’t give my name to a mule, man,” she cursed. “If you did, I’ll skin you and your mule alive.”

She turned her back on him, as he laughed, then started in with more of his beguiling talk.

She listened to him skeptically, trying to resist his advance, even as she half wished for all he said to be true. More than that. She wanted all of it to be all true, all of her wanted that, but she knew she only had less than half a man and wondered what that was worth if you followed it somewhere. “This is what you leaving cost the two of us.”

“It’s not me going, it’s being bonded to begin with,” he answered.

She did not respond but allowed him to draw in closer as they negotiated whether it would be a night of greater or lesser rest.

In the morning, before Ruth set out, there came a knock at the door. When she opened it a small child blurted that Mrs. Sorel said Merian should come by the house and say hello.

Ruth looked at Merian and asked whether he had heard.

“Tell her I’ll be there directly,” he answered. He had thought fitfully about how he would encounter the Sorels on his ride from Stonehouses, but the scenarios always pushed against, then overflowed, the boundaries of his imagining. Now, once it was put to him, he tried to assume the best possible mood. He finished dressing and went up to the house as commanded, mindful of his original purpose in coming.

In the kitchen he greeted the new cook cordially and sat down familiarly to wait for his audience with Mrs. Sorel. Sitting there he felt like a younger version of himself and tried to remind himself of all that had changed for him since he lived here.

Nothing proved changed, though, when Hannah Sorel entered the kitchen. He found himself standing promptly then as on any day in the past to greet her.

“Jasper, Mr. Sorel is at Richmond,” she said, sweeping into the room. “He will be upset to have missed you.”

Merian’s breath stopped in his chest but he was quick to mask the fact, asking how she had been and admiring how much the place seemed to be prospering.

“It is not the same since you left,” she answered. “I’m almost sorry we let you go.”

“Well, I’m almost sorry I left,” he replied, playing in this game with her.

She asked him again how he was getting on and then whether he had been keeping up with church. “You haven’t joined with those Congregationalists or any nonesuch out there, have you?”

“I hardly know what that is,” he said, assuring her he kept much to his own company as he had always done. He asked again when she said Mr. Sorel would be getting back. “Because I actually wanted to speak to him, if I could, about Ruth and Magnus.”

“I see,” Mrs. Sorel answered, smoothing the top of her salt-and-pepper head and looking out the window, as his intention became clear to her. “Jasper, I don’t think he will go along with it. You must know that already. Peter doesn’t run things as Father did, and he doesn’t believe in selling slaves, let alone freeing them.” She said her words all at the same time, not at all certain how she should answer her former slave. “In any case, he is away until the middle of next month.”

Merian looked around the kitchen, which unlike the rest of the house had barely changed since it was first put up. He had been there with them since the beginning, when they were newlyweds, and counted this room among the ones he had joined in building.

“Mrs. Sorel, fair is fair,” he protested.

“I wish I could believe that as true, Jasper,” she replied.

He knew she was being honest with him, and that there was little in her power to do. His own manumission had been on terms set by the original estate, not her husband’s. The old man dictated his fate, as he did everything else when he lived, allowing him to leave either because of caprice of will or because he had served them so well from the beginning, as he had stated – when she was setting up house with the strange planter from Barbados and Jasper was her only reminder of home. Her father had made her promise as much when he presented her with him.

“How much do you think he might want?” Merian asked, returning to business.

“I don’t know, Jasper.” She could barely look at him as she said this. “I am glad to see how well you’re doing for yourself in the new colony, though. You must come back to visit them again.”

Their congress concluded, she left the kitchen, telling the cook to fix him something for his belly. “He’s getting thin down there so far from home.”

Her last words stuck in his ear, as he thought how he had lived over half his life here and grown all the way from child to manhood. He even allowed that he felt more a part of Sorel’s Hundred than he did his own place in many ways, but he did not want it to be his own family’s home. He thought then of Hannah Sorel’s father, who had always called both him and Hannah little Columbians. He wondered at the time what had been meant by this, but it was a bond to the place and the daughter through the father, not the strange island man she married or his British friends, who hung about the house scheming adventures that should never be allowed to transpire.

When he left there that evening, his trip a failure, he pressed on Ruth the money he had brought to purchase them out with.

“What do you want me to do with this?” she asked.

“When he comes back see whether you can still do it. Go to her first, though, not him.”

“Is that it?” she asked. “Is that all?”

“Ruth, what else do you want me to do?” he demanded of her sharply. “I am just a man and have done all I have it in me to do. I need to get back to my own place now.”

“Yessir, my own place,” she taunted him. “Go say good-bye to your boy now. Make sure you tell him you did all you had it in you to do.”

Her cruelty stung at him, but as he hugged Ware good-bye he told her again, “Do like I said.”

Ruth began to weep as he went to his horse, leaving them a second time trapped in captivity with little chance of ever seeing him again. Less than little, she thought, realizing his new woman was unlikely to let him get away a second time. She tried the word never in her mouth and knew immediately that is what it would be.

* * *

He spurs the horse and looks out on the gray horizon, heavy with a black storm cloud that darkens and gathers everything around itself, like spilt ink on a blotter. It is the Columbian sky. He hurries on beneath it back to Stonehouses.