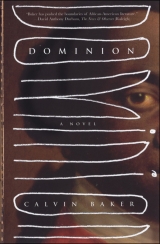

Текст книги "Dominion"

Автор книги: Calvin Baker

Жанр:

Историческая проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

eight

Purchase ranged the countryside in desolation after Mary Josepha left him, sometimes earning his living by honest means and sometimes in more expeditious fashion. A month after she went back to her husband he knew he would not forget her but made it through the winter alone as best he could. Nor was his heart heavy with anything else that winter, except failing in his union with her.

He was almost in Maryland before he found her again and, after much persuading, convinced her to come off with him. It seemed to him it was either easier than before or else he no longer felt the pain of what he went through. This time, so say the stories that eventually sprang up around the two of them and reached Berkeley, he swore he would employ all his powers of strength and intelligence to keep her. When she came to him then, in a rented room, he put a potion in her drink that made her sleep very sound. She awoke in an impenetrable cage of his besotted construction.

He had dreamed of that enclosure all the way from the border of Florida to where they were now. At night small details would come to him, and he would get up then and there to jot down a diagram of what had been revealed to him.

The bars of the jail were stronger even than the blade of the sword he had made for his father, and the lock was of ingenious design. No one would ever break it or learn its secret mechanism. The entire contraption was exceedingly light as well, so that it could be taken up and put in the back of a wagon, suspended in air, or even floated on water. Inside he tried to make it as comfortable as possible for her, and when they were not on the move it had a mechanism that allowed him to expand it and give her more room. In all those hours without her he had figured out how to make the cage perfect for what it was and escape-proof. If it was cruel he did not see it, only that it accomplished his goal and kept her near him.

The only time he opened the door was to give her food, or when he wanted to be with her. For a month she suffered this fate, until one day she suddenly warmed to him again, calling out for him to come to her of her own accord. They were happy like this for many weeks. It was after one of these episodes, though, that he awoke to find himself imprisoned in his own trap and Mary Josepha gone back to the Englishman.

It took him twice as long to escape the dungeon as build it. When he finally was able to let himself free he was bitter with a disgrace that forbade him from returning home, as he should have, so he continued roaming northward until he could forget or else find a way to redeem who he had become. He swore this time he would not go after her again either but reflect upon what he had learned those months, until the suffering itself had become a kind of balm and solace. “Suffering has always been the price of God’s love,” Mary Josepha used to say to him, when he had convinced her to come off with him, just before she left. He did not feel loved, though. He felt hated, and he was all the way down bitter with himself over what he had done. For he was no longer Purchase of Stonehouses but someone far removed.

He was working in Rhode Island in a shipyard when she finally came to him of her own free choice. She was with a small child and said Oswin had put her out, claiming to know it was not his and no way would it ever be passed off as such.

He took her in, and they lived for a while in great harmony, each forgiving the other for the things they had done to cause one another misery. They lived above the smithy where he worked, and the rooms were always warm from the furnace, and she set about making a home for the three of them there. He had long ago melted the cage down, and from its remains crafted a great wrought-iron bed, which they slept on as husband and wife, for she claimed that a man and woman could marry themselves to each other with no more officiating than that. That it was the way it had always been done until the church thought to step in and charge a fee, but the institution was still built of just two people.

Whatever this state was called, it was blissful to him, and he went to work regular most mornings, except those he stayed home to be with her. On those holidays he always worked late into the evening the following day so that they always had dependable meals and warm clothes against the seaside winters. From this routine, life in the house took on the contours of regularity that did much to ease both their minds.

She had come over from Africa not ten years earlier and Oswin had originally been her master, until he had a vision one night and immediately upon waking repented of how he lived, saying now that it was not proper for one human to own another. When he set his slaves free he had thirty other souls he had been responsible for during the previous portion of his life. He told them they were all permitted to go, but he said to Mary Josepha that he would be much pleased if she stayed with him of her own volition. It surprised her, for he had never seemed to so much as look at her before. She agreed to stay with him, and they were happy awhile.

In time she found he was a very jealous husband and snuck off with Purchase, at first to punish him. The second time, however, it had been because she had found she preferred to be with Purchase and had no want of punishing anyone, if such were possible.

They wrestled with this for the years they were on the road together, him telling her she was his wife and her saying it was difficult to find a difference between that and being his slave. Shamed, he would be silent a bit, but when she abandoned him for Purchase he beat her to within an inch of her life. The next day, heavy of heart, he gave two very popular sermons: the first was about the rights of slaves to freedom, and the second was about the duty of the wife and the pain of marriage. “Both are among the truest penance to God,” he claimed. That day they saved two dozen souls, more if one included the slaves one of the parishioners set free after the sermon.

Purchase was irresistible to her after that and she had come to him in Maryland intending to stay, until she found herself in the cage. When she returned to Oswin he at first took her in, and even kept her after he saw her condition, thinking perhaps it was his issue she bore. As soon as the child was born, though, he put them both out in the snow. He himself died very soon afterward, of an affliction either of the nervous system or of the blood. He had two different doctors and on this final diagnosis neither could agree.

That winter and spring husband, wife, and child were all content as could be in the warm little room above the shop, and when summer came they talked of visiting Stonehouses. It was put off because of Purchase’s work, which picked up during the warm months, and on account of the child still being so small, but Mary Josepha gave every impression of being the most diligent of mothers. She seemed to be rid of the wandering that was in her blood before.

When Purchase came upstairs from the workshop she would have a meal waiting for him, and on Sundays they went to the Baptist church together for worship and praying on the things they could find no other answers for, or refuge from, in daily life.

It was here she first felt the need to minister again. Even though Rhode Island was the most liberal of the colonies, there was not yet a significant congregation of people who professed as they did, for Purchase had come to be an adherent of her unorthodox beliefs as well. She expressed her dissatisfaction at first by attending different churches to hear what their ministers had to preach. Usually she went for no more than a week, but sometimes she would maintain interest in a congregation for as long as eighteen months before moving on, until she had been to nearly every church in Providence. In the end she knew it was simply no use. They were none of them as liberal as they preached, all were beholden to an ordering she recognized as false, and none could explain these falsehoods away.

She began to give sermons in the square on her own, but what had been popular among the country people caused a great sensation in the town. There were two principal charges brought against her. The first was that she was uneducated and so could not interpret the Gospels; no one claimed her to be heretical, because heresy requires knowing and they denied her ability in this endeavor. The second was that she was a woman and, on those grounds alone, should stop and desist.

When they brought the complaint, they first spoke to Purchase, but he supported her steadfastly. “If she has it to preach, I don’t see the harm. There’s a thousand churches in Providence.” The response did not endear him to anyone and soon his business began to decline, among both the whites and free Negroes.

Purchase told her it was nothing to cause them worry, and they would withstand the privations of opinion. For Mary Josepha, however, it was more than people talking against her, it was that she could not practice her chosen craft and belief. “It is my calling, and the price of God’s love has always been and ever will be suffering,” she repeated, and he knew this is what she truly believed and that he was in danger of her leaving. “Better a liar with true words than a false prophet and none of it worth telling.”

He did not want to know anything more about that kind of love and told her they would leave the state and return the coming autumn to his people at Stonehouses, where there was always a place for them.

What she wanted foremost was to preach, and to know again the feeling of bringing souls to God on what she thought of as reasonable terms, even if there was theater out in front of that. “I will have the same problem there as here,” she said. “The only way to keep going for me is to move and not rest still.” He told her they should at least try his people first before settling into that kind of life, as he did not think it would be any great bargain for any of them.

He returned from work one day soon after that to find her gone again, as he had all those days in the past. This time, however, he was not frantic in his action but very deliberate. It was northern autumn and already beginning to freeze over during the nights.

He dressed the boy in heavy shoes and a thick warm sweater underneath a heavy coat. His head was covered in a woolen hat. Purchase affixed a bag containing some coins of silver in the pockets of his coat and another of gold inside his sweater. He also wrote two notes, one for the messenger and another for the receiver.

He then took the boy in his arms and carried him out into the night and to the other side of Providence, down near the quays. It was the home of one of his friends and customers, a half-caste sailor named Rennton who belonged to the Antinomian church with his wife and often did business in the farmost reaches of the Crown’s possessions, including the southern colonies.

In his father’s arms the boy felt safe when they left the house, but soon a sense of dizziness overtook him as they bounded over the small hills, which looked enormous from his perspective, and moved toward the fish smell of the docks. He knew something strange was afoot, but when his father set him down on the unfamiliar porch and told him to stay quiet, the child obeyed. He was still quiet an hour later when Rennton came home and found him there, and in fact would not speak for two full days afterward.

Purchase he could not help but go off again after Mary Josepha, as he had those days in the past when she still had another man and he chased after her. Both of them like the original Fools, or else original Lament and Heartache.

Rennton took the child inside his little house and asked his wife to feed him from their pot. While the child ate he unpinned the note from his coat and went out to his neighbor’s place to have it read. He did not need anyone to tell him that something was amiss with the boy and that in likelihood he had been abandoned. It seemed too important a thing to guess at, though, and not be entirely certain. What if they only wanted to leave the child for a little while and then come back? But leaving him out there in the cold, Rennton knew, was the same as giving him away.

He apologized to his neighbor for coming at such an hour, but when he showed him the note the man marveled at the audacity of it. “Imagine them not just leaving the boy free and clear but leaving him with a lien they want you to pay off.” Rennton thanked him for reading the note and went back to his own house, puzzling more how Purchase could do something like that than the inconvenience it would cause him.

When he returned he told his wife what Purchase and Mary Josepha had done, and she argued with him that it was Purchase who had done more wrong, because Mary Josepha only left the child with its father, as you would if going to the market or away for a visit to relatives.

Rennton did not argue with her – he never argued with her – but said he would take up the task Purchase had left to him – as it was good friendship, and someone had to take up responsibility for the little creature – and try, beginning the day after next, to deliver the boy safely to the place in the note. The boy, Caleum he was called, felt very safe in that house for the two days he was there and seldom cried for missing his parents. He was a manual of composure, and no one watching him would have known any of this, especially as he held his tongue and did not speak.

When they set out for Stonehouses, though, the boy was at first upset by the voyage and the life of the sea. He was almost as disturbed by the journey from Providence to Edenton as he had been when he finally realized for himself that his parents were gone away without him and what his condition was. Rennton, when he addressed him, always started out calling him Caleum, but in the end found himself saying poor boy or pitiful orphan.

It was on this voyage that Caleum began to speak again and ask his fate, as the sounds of the ship and its other passengers had unsettled him so he did not know what would become of him. Looking over the side of the vessel as they rounded Cape Lookout, the ink-dark water seemed lit from underneath by a strange, ominous light that would show itself if only the waves could part far enough. He looked at this mystery, hoping the water would leap higher and show the bottom of the ocean, but soon the waves began to toss the ship and make it creak with a horrible sound that seemed to him like an old person screaming. He ran back from the rail and sought out Rennton in the excitement of the sailors trying to fasten down the ship for the storm they had entered. When he found his caretaker, he could only think to ask him if they were going to hell. He asked this very calmly, as if he were prepared should that be their ultimate destination.

Rennton told the boy they were going to no such place but were only caught in a squall such is normal at sea in that season. Caleum went back to the rail of the ship and looked out again. This time he spied another boat on the horizon that was sailing under calm winds, and a young couple stood at the rail holding hands. The woman, seeing the boy, kissed her hand with great intensity then blew the kiss to him. Although she looked very different, and he had never seen her before, he felt when he received it that he had been kissed by his own mother. He waved back to the other ship, until they were nearly gone from sight, and the wind in the sails of his boat forced him to seek shelter below.

Rennton, when the boy came back, tried his best to console him, but he could not help worrying aloud what they were thinking to leave him in such a state of safety. He did not judge them though, and while not one man in a hundred thousand would have done what he did, he was good as the trust Purchase placed in him. When the boat docked in Carolina they disembarked, and the two continued overland together toward Stonehouses.

nine

In the end it was Sanne who made a way for Adelia in Magnus’s affections, years after the start of the affair and even then under the most terrible of circumstances.

The night after she saw him riding away in the snow, Adelia knew Magnus was lost to her. While he sat in the tavern, she allowed her desire for him to seize and run rampant in her imagination. When he stood and, instead of coming to beg her forgiveness, went away, her heart clinched inside her chest and she lost her breath briefly. While he sat out on the horse in the snow, she was aware of him watching her and still thought it only a matter of time before he came back and they were together. When he rode off into the darkness, though, Content had to close the tavern, so distraught was she to see him ride away.

Nor would she come down from her room upstairs in the days that followed, and whenever Dorthea brought her food she sat at the edge of the bed and shoved it away, asking, “What have I done to be treated like this?”

All the sympathy and outrage shown to her, though, did nothing to move Magnus. Sanne, seeing how he behaved, knew it was not how he wished to be. Still, when she prayed at night, she began to wonder whether he was not hardening heaven against himself.

That was in the days immediately before illness took her, and life at Stonehouses changed forever.

When she first noticed it, one day in early spring, the crab on her chest was already livid, and extended out over her breast like a lover’s jealous hand. When she gazed upon it she thought of her former husband, and how, when they were still a young couple, he would sometimes clutch her with maddening force as he swore his love. She guarded the crab as a secret for months then, as she had once guarded his affection for her.

When its limbs spread and began grasping for the other side of her body, though, she could no longer bear it. “This much will always be yours. All the rest belongs here to Jasper Merian and Stonehouses,” she told her first man, unhappy to have him reaching for so much from where he was.

After breakfast she sent her new girl into town with a note, which the girl left at the doctor’s place at lunchtime. He came round to Stonehouses before supper. After the examination he told her she could be happy that they now had hemlock, which was much better than previous medicines to treat such things, and that this procedure was not known even two years before in London, let alone in the colonies.

She thanked him and, in the months that followed, consumed a potion of hemlock twice a day, increasing the amount of the herb bit by bit, until what she ate in the third month would have been enough to murder a bull. There was no effect on her, but neither did her condition worsen. The doctor, when he came around, said recovery was only just around the corner.

When the crab began to grow again and turn scirrhous, he recommended to then a treatment of mercury and poultices. Sanne felt her strength beginning to depart around this time, and the afternoon walks she took to breathe of the deep pine air began to grow shorter, until she could barely make a full turn through her garden. This is when she sent to town to get Adelia back from Content’s. The girl came to her immediately, not thinking of Magnus but only that Sanne, that soul of piety, needed her aid.

She nursed her for six months, giving her her medicines and applying a poultice twice a day, the first made from bark, the second from mercury. When the symptoms failed to go away the doctor began to let her blood with leeches, saying such diseases were caused by malign humors that needed only to be released. He prescribed a new poultice of nightshade and told Sanne she must have her daily walk no matter how short it was.

Each morning Adelia would wrap the old woman warmly and take her arm, and they would go out into the garden in front of the house. Both Merian and Sanne had been delighted by that garden when they finally had the luxury one spring to plant flowers instead of simply vegetables. As she walked there now, though, she saw Samuel, her first husband, walking beside her and looking continuously at the sundial as if waiting on another appointment. “Do you have somewhere else to be?” she asked him.

“No,” he replied, “I’m here at your service, but if it would please you I might finally take you back over the ocean and show you my home, as we always talked about in our youth.”

She was not frightened by this discourse as might be reasonably expected. On the contrary, it soothed her and took her mind from her pain to have such steadfast company.

When the second treatment regime failed, and the ichor began to run, the doctor advised both Sanne and Merian that the only recourse was to try to cut away the diseased tissue. By then the hand that held Sanne had become a claw, and they both knew neither poultices nor surgery was very likely save her.

“You have been very good to me,” Merian said to her that night after the doctor had gone, holding her frail hand. “I could not have made half of what I did without you.”

“And I never thought you would build so great a property when I married you,” she answered him. “Or make me so happy.”

“It has been better than we dared to hope,” Merian said, giving her hand a light, affectionate squeeze.

“What will happen to my orphans now?” she asked.

He did not answer her but smoothed her hair.

The next day she sent out on the farm to have Magnus come to her. In the years he had been there Magnus had changed immensely to anyone regarding him. Gone was the hard, weary look he carried when he first arrived, and his face, while still lean, had taken on a pleasing softness. Still, there was a hunger about him that was etched within and had never gone away completely. As he stood at Sanne’s bedside, she tried to turn her head to get a better look at him but was weighed down with drowsiness from the opium tablets she now consumed four times a day.

Looking at her, Magnus could not but think how empty that house would be when she was gone from it. “Ware,” she said, unconsciously using that name that no one but his parents called him by, “Come closer.” He sat at the edge of her bed and thought how he had once been frightened of her when he originally came. He thought then she might put Merian up to sending him away, but they had grown close enough over time.

He was completely quiet as she spoke softly, and he had to bend down over her to hear, until he found it easier to kneel at the side of the bed. He was very tense that she might require something he could not do, but whatever she asked he would strive in earnest to fulfill.

“I want you to promise me you will take care of your father,” she said. “He is old and soon will no longer be able to care for himself properly.”

“Of course I will do that,” he answered. “You never have to worry about it.”

“Do you still care for Adelia?” she asked next.

“I have not thought much about it,” he replied, taken aback.

“I want you to marry her,” Sanne said simply. “This has gone on long enough, and you will need someone.”

“Sanne, I am not certain—” he began to protest, but she started coughing violently. When her cough had quit her she told him not to disagree.

“Just do as I say,” she went on. “If you ever loved my lost son or your own mother. If I ever made a home for you, I want you to obey me in this. It is hard enough to lose one son. I don’t want to think the same kind of thing could happen to you, and you just get swept away by the first wind blowing.”

“Sanne,” Magnus answered, even as his thoughts weighed heavily upon him, “I would do it even if you had done none of those things for me but only because you ask.”

“Good,” she replied, smiling. “What a good man you are becoming.” She wished nonetheless she could instruct him in those things about marriage and domestic life that only women can adequately tell, but she was overtaken by the opium and began to doze, happy for this last victory she had secured in the household.

The next morning, when the doctor came to perform surgery, Merian was by her side until the very last minute. She clasped his hand tightly as the surgeon gave her another dose of medicine to help her bear the pain, both that which she carried every day as well as that of the pending operation. As she looked at her husband, she thought about their courtship and how they used to sing to each other during their first days of marriage. She remembered as well their strife and how close to starvation they were during those early winters. It had been at last a good marriage, and she wished to let him know how joyful he had made her, and all that is tender. The drug, though, had already begun to claim her consciousness – so that when she opened her mouth to speak, the words were all a murmuring flow. Undaunted she still held on to her husband and began to hum to him that song she learned from her grandmother so long ago. The last thing she heard as her eyes fell closed was her husband singing back to her the refrain.

The operation went poorly. The doctor managed to remove the claw that gripped her, but it was so large by that point he had also to take away the majority of her chest muscle. When she awoke from the surgery it was only very briefly and what she felt was a lightness.

She was not so strong as to move her head, but she knew her first husband was trying to claim her with even greater force than before. Sure enough, when she was finally able to look around she saw him sitting by the side of her bed holding one hand as Merian held the other.

While Merian only clung to her in brief intervals, visiting four or five times a day, her first man never left her side. “I lost you once, girl,” he said. “I have no aim of doing so a second time.”

“Yes,” she said, knowing what he wanted. “I will come away with you.”

When Merian came into her room that evening, it was three days since her operation and the ichor still had not finished draining from her wounds. She was inflamed with it and he could she what pain she endured, lying there wrapped in the covers of their marriage bed.

“How are you this evening, Sanne?” he asked.

She no longer recognized him. She saw only a very old man at her side and wondered who it was who had found his way into her room. She looked around then, wondering where Merian was, because it was the time he usually came and he was always very punctual.

When the old man took up her hand, she grew increasingly frightened and began to scream out that he would have Jasper Merian to contend with if he treated her roughly. When Merian still did not come she screamed even louder, until her first husband appeared at her side and took her finally in both his hands.

Before, he had only held her by the fingers or else offered an arm as they strolled in the garden of Stonehouses, but this time he lifted her up as he had on their wedding night and promised no harm would befall her ever.

“I will take care of you,” he pledged.

“Where we will live? Where are we going now?” she wanted to know.

“Back across the ocean, my love,” he answered to her. “Remember?”

“Will I like it there?” she asked.

“You will. We will make a house for our love.”

“What if I do not?”

“You mustn’t leave me again,” he said.

“You can’t ask me this.”

“I am your husband again.”

“Yes,” she said, recognizing the truth. “I will try to be a good wife and make a good home for us there across the ocean.”

“You were always the best wife ever there was.”

“That was on the coast,” she answered. “I do not know how it will be for us across the sea.”

“You know many people there,” he assured her.

“Merian is not there,” she said, “nor Purchase. Merian is still at Stonehouses, and my son Purchase is gone. Will they join us?”

“You must rest,” he told her. “It is a long journey.”

“Yes, we must start out.”

The two of them left together then, as he took Sanne in his arms away from Stonehouses, back over the ocean. Once more across the sea.

At her wake Merian spoke very little, being both too lonesome to talk and upset at having the preacher in the house. Standing afterward in the meadowland he had long ago claimed for a graveyard he only listened as the preacher finished his sermon and Magnus and the other pallbearers began to fill in her grave. He was himself too old to shovel the soil back into place but could only watch until they were finished with the task. When they were done, and the grave was stilled over with earth, he issued to them one final instruction. “Dig mine just next to it.”

“Yea, there will be time for that,” Content said, standing beside his ancient friend.

“It was you and Dorthea who brought us together,” Merian replied. “You did not tell me then it would be so short a while.”

He walked over to the preacher and pushed a handful of coins into his hand, then turned and went back toward the house.

When the other mourners entered, Adelia had laid a table with foods and tried her best to make everyone comfortable, recalling from earlier times what the visitors and inhabitants of Stonehouses each required – so that when Content called for something they were able to offer him an eau de vie, and the doctor had his claret, and Magnus, when he went to the table, found a small pot of warm milk with his coffee.

He picked it up and smiled at her as he brought the cup to his lips. This was their first intimate interaction since she had come back to the house; he had done his best to avoid her the entire time, knowing she was there on Sanne’s account and not his, and he did not want her to be reminded of their troubles before.

As he looked at her he remembered what he promised Sanne on her deathbed. He knew she would not have told Adelia what had been agreed upon between the two of them, and he struggled to decide whether he was bound to an old woman’s delirious request. He had managed in the time he had been there to find appropriate means of dealing with those urges he could not control, but for the rest he felt as he had all his life. Seeing Adelia then made him curse himself for being so quick to give in to what Sanne had asked of him. He did not know if he could maintain his end of the deal, or even if she would still want him should he presume to try.