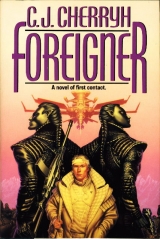

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

Most of all, atevi weren’t incapable of making technological discoveries completely on their own… and had no trouble keeping them prudently under wraps. They were not a communicative people.

They reached the door. He used the key Banichi had given him. The door opened. Neither the mat nor the wire was in evidence.

“Ankle high and black,” Banichi said. “But it’s down and disarmed. You did use the right key.”

“ Yourkey.” He didn’t favor Banichi’s jokes. “I don’t see the mat.”

“Under the carpet. Don’twalk on it barefoot. You’d bleed. The wire is an easy step in. You can walk on it while it’s off. Just don’t do that barefoot, either.”

He could scarcely see it. He walked across the mat. Banichi stayed the other side of it.

“It cuts its own way through insulation,” Banichi said.

“And through boot leather, paidhi-ji, if it’s live. Don’t touch it, even when it’s dead. Lock the door and don’t wander the halls.”

“I have an energy council meeting this afternoon.”

“You’ll want to change coats, nadi. Wait here for Jago. She’ll escort you.”

“What is this? I’m to have an escort everywhere I go? I’m to be leapt upon by the minister of Works? Assaulted by the head of Water Management?”

“Prudence, prudence, nadi Bren. Jago’s witty company. She’s fascinated by your brown hair.”

He was outraged. “You’re enjoying this. It’s not funny, Banichi.”

“Forgive me.” Banichi was unfailingly solemn. “But humor her. Escort is so damned boring.”

II

« ^ »

It was the old argument, highway transport versus rail, bringing intense lobbying pressure from the highway transport operators, who wanted road expansion into the hill towns, versus the rail industry, who wanted the highspeed research money and the eventual extensions into the highlands. Versus commercial air freight, and versus the general taxpayers who didn’t want their taxes raised. The provincial governor wanted a highway instead of a rail spur, and advanced arguments, putting considerable influence to bear on the minister of Works.

Computer at his elbow, the screen long since gone to rest, Bren listened through the argument he’d heard in various guises—this was a repainted, replastered version—and on a notepad on the table in front of him, sketched interlocked circles that might be psychologically significant.

Far more interesting a pastime than listening to the minister’s delivery. Jago was outside, probably enjoying a soft drink, while the paidhi-aiji was running out of ice water.

The Minister of Works had a numbing, sing-song rhythm in his voice. But the paidhi-aiji was obliged to listen, in case of action on the proposal. The paidhi-aiji had no vote, of course, if the highway came to a vote today at all, which didn’t look likely. He had no right even to speak uninvited, unless he decided to impose his one real power, his outright veto over a council recommendation to the upper house, the tashrid—a veto which was good until the tashrid met to consider it. He had used his veto twice in the research and development council, never with this minister of Works, although his predecessor had done it a record eighteen times on the never-completed Trans-montane Highway, which was now, since the rail link, a moot point.

One hoped.

There was the whole of human history in the library on Mospheira, all the records of their predecessors, or all that they could still access—records which suggested, with the wisdom of hindsight, that consuming the planet’s petrochemicals in a vast orgy of private transport wasn’t the best long-range choice for the environment or the quality of life. The paidhi’s advice might go counter to local ambitions. In the case of the highway system, the advice had gone counter, indeed it had. But atevi had made enormous advances, and the air above the Bergid range still sparkled. The paidhi took a certain pride in that—in the name of nearly two hundred years of paidhiin before him.

The atevi hadn’t quite mastered steam when humans had arrived on their planet uninvited and unwilling.

Atevi had seen the tech, atevi had been, like humans, eager for profit and progress—but unlike humans, they tended to see profit much more in terms of power accruing to their interlocked relationships. It was some thing about their hardwiring, human theorists said; since the inclination seemed to transcend cultural lines; a scholarly speculation useful for the theorists sitting safe on Mospheira, not for the paidhi-aiji, who had to make practical sense to the aiji of the Ragi atevi in the city of Shejidan, in Mospheira’s nearest neighboring Association and long-term ally—

Without which, there might be a second ugly test of human technology versus atevi haroniin, a concept for which there was no human word or even complete translation. Say that atevi patience had its limits, that assassination was essential to the way atevi kept their social balance, and haroniinmeant something like ‘accumulated stresses on the system, justifying adjustment.’ Like all the other approximations: aiji wasn’t quite ‘duke’ it certainly wasn’t ‘king,’ and the atevi concept of countries, borders and boundaries of authority had things in common with their concept of flight plans.

No, it wasn’t a good idea to develop highways and independent transport, decentralizing what was an effective tax-supported system of public works, which supported the various aijiin throughout the continent in their offices, which in turn supported Tabini-aiji and the system at Shejidan.

No, it wasn’t a good idea to encourage systems in which entrepreneurs might start making a lot of money, spreading other entrepreneurial settlement along roadways and forming human-style corporations.

Not in a system where assassination was an ordinary and legal social adjustment.

Damn, it was disturbing, that attempt on his apartment, more so the more time distanced him from the physical fear. In the convolutions of thinking one necessarily was drawn into, beingthe paidhi—studying and competing for years to be the paidhi, and becoming, in sum, fluent in a language in which human words and human thought didn’t neatly translate… bits and pieces of connections had started bobbing to the surface of the very dark waters of atevi mentality as he understood it. Bits and pieces had been doing that since last night, just random bits of worrisome thought drifting up out of that interface between atevi ideas and human ones.

Worrisome thoughts that said that attacking the paidhi-aiji, the supposedly inoffensive, neutral and discreetly silent paidhi-aiji… was, if not a product of lunacy, a premeditated attack on some sort of system, meaning any point of what was.

He tried to make himself the most apolitical, quiet presence in Tabini’s court. He pursued nocontact with the political process except sitting silently in court or in the corner of some technological or sociological impact council—and occasionally, very occasionally presenting a paper. Having public attention called to him as Tabini had just done… was contrary to all the established policy of his office.

He wished Tabini hadn’t made his filing of Intent—but clearly Tabini had had to do something severe about the invasion of the Bu-javid, most particularly the employer of the assassin’s failure to file feud before doing it.

No matter that assassination was legal and accepted—you didn’t, in atevi terms, proceed without filing, you didn’t proceed without license, and you didn’t order wholesale bloodbaths. You removed the minimal individual that would solve a problem. Biichi-gi, the atevi called it. Humans translated it… ‘finesse.’

Finesse was certainly what the attempt lacked—give or take the would-be assassin hadn’t expected the paidhi to have a gun that humans weren’t supposed to have, this side of the Mospheira straits.

A gun that Tabini had given him very recently.

And Banichi and Jago insisted they couldn’t find a clue.

Damned disturbing.

Attack on some system? The paidhi-aiji might find himself identified as belonging to any number of systems… like being human, like being the paidhi-aiji at all, like advising the aiji that the rail system was, for long-range ecological considerations, better than highway transport… but who ever absolutely knew the reason or the offense, but the party who’d decided to ‘finesse’ a matter?

The paidhi-aiji hadn’t historically been a target. Personally, his whole tenure had been the collection of words, the maintenance of the dictionary, the observation and reporting of social change. The advice he gave Tabini was far from solely hisidea: everything he did and said came from hundreds of experts and advisers on Mospheira, telling him in detail what to say, what to offer, what to admit to—so finessing himout of the picture might send a certain message of displeasure with humans, but it would hardly hasten highways into existence.

Tabini had felt something in the wind, and armed him.

And he hadn’t reported that fact to Mospheira, second point to consider: Tabini had asked him not to tell anyone about the gun, he had always respected certain few private exchanges between himself and the aiji, and he had extended that discretion to keeping it out of his official reports. He’d worried about it, but Tabini’s confidences had flattered him, personally and professionally—there at the hunting lodge, in Taiben, where all kinds of court rules were suspended and everyone was on holiday. Marksmanship was an atevi sport, an atevi passion—and Tabini, a champion marksman with a pistol, had, apparently on whim, violated a specific Treaty provision to provide the paidhi, as had seemed then, a rare week of personal closeness with him, a rare gesture of—if not friendship, at least as close as atevi came, an abrogation of all the formalities that surrounded and constrained him and Tabini alike.

It had immensely increased his status in the eyes of certain staff. Tabini had seemed pleased that he took to the lessons, and giving him the gun as a present had seemed a moment of extravagant rebellion. Tabini had insisted he ‘keep it close,’ while his mind racketed wildly between the absolute, unprecedented, and possibly policy changing warmth of Tabini’s gesture toward a human, and an immediate guilty panic considering his official position and his obligation to report to his own superiors.

He’d immediately worried what he was going to do with it on the plane home, and how or if he was going to dispose of it—or report it, when it might be a test Tabini posed him, to see if he had a personal dimension, or personal discretion, in the rules his superiors imposed on him.

And then, after he was safely on the plane home, the gun and the ammunition a terrifying secret in the personal bag at his feet, he had sat watching the landscape pass and adding up how tight security had gotten around Tabini in the last few weeks.

Thenhe’d gotten scared. Then he’d known he had gotten himself into something he didn’t know how to get out of—that he ought to report, and didn’t, because nobody on Mospheira could readthe situation in Tabini’s court the way he could on a realtime basis. He knew that some danger might be in the offing, but his assessment of the situation might not have critical bits of data, and he didn’t wantorders from his superiors until he could figure out what the undercurrents were in the capital.

Thatwas why he had put the gun under the mattress, which his servants didn’t ordinarily disturb, rather than hiding it in the drawers, which they sometimes did rearrange.

That was why, when a shadow came through his bedroom door, he hadn’t wasted a second going after it and not a second more in firing. He’d lived in the Bu-javid long enough to know at a very basic level that atevi didn’t walk through people’s doors uninvited, not in a society where everyone was armed and assassination was legal. The assassin had surely been confident the paidhi wouldn’t have a weapon—and gotten the surprise of his life.

If it hadn’t been a trial designed to catch him with the gun. Which didn’t say why—

He was woolgathering. They were proposing a vote next meeting. He had lost the minister’s last remarks. If the paidhi let something slip unchallenged through the council, he could end up losing a point two hundred years of his predecessors had battled to hold on to. There were points past which even Tabini couldn’t undo a council recommendation—points past which Tabini wouldn’tundertake a fight that might not be in Tabini’s interest, once he’d set Tabini in a convenient position to deny his advice, Tabini being, understandably, on the atevi side of any questionable call.

“I’ll want a transcript,” he said, as the meeting broke up, and gathered a roomful of shocked stares.

Which probably alarmed everyone unnecessarily—they might take his glum mood for anger and the postponement and request for a transcript as a forewarning that the paidhi was disposed to veto.

And against what interest? He saw the frown gather on the minister’s face, wondering if the paidhi was taking a position they didn’t understand—and confusion wasn’t a good thing to generate in an ateva. Action bred action. He had enough troubles without scaring anyone needlessly.

The Minister of Works could even conclude he blamed someone in his office for an attack that was surely reported coast to coast of the continent by now, in which case the minister and his interests might think they should protect themselves, or secure themselves allies they believed he would fear.

Say, I wasn’t listening during the speech? Insult the gentle and long-winded Minister of Works directly in the sorest point of his vanity? Insult the entire council, as if their business bored him?

Damn, damn, a little disturbance in atevi affairs led to so much consequence. Moving at all was so cursed delicate. And they didn’tunderstand people who let every passing emotion show on their faces. He took his computer. He walked out into the hall, remembering to bow and be polite to the atevi he might have distressed.

Jago was at his elbow instantly, prim Jago, not so tall as the atevi around her, but purposeful, deliberate, dangerous in a degree that had to make everyone around him reassess the position he held and the resources he had.

Resources the aiji had, more to the point, if, a moment ago, they had entertained any uneasiness about him.

There was another turn of atevi thinking—that said that if a person had power like that, and hadn’t used it, he wouldn’t do so as long as the status quo maintained itself intact.

“Any findings?” he asked Jago, when they had a space of the hall to themselves.

“We’re watching,” Jago said. “That’s all. The trail’s cold.”

“Mospheira would be safer for me.”

“But Tabini needs you.”

“Banichi said so. For what? I’ve no advisements to give him. I’ve been handed no inquiry that I’ve heard of, unless something turns up in the energy transcript. I’m sorry. My mind hasn’t been on business.”

“Get some sleep tonight.”

With death-traps at both doors. He had nothing to say to that suggestion. He took the turn toward the post office to pick up his mail, hoping for something pleasant. A letter from home. Magazines, pictures to look at that had human faces, articles that depended on human language and human logic, for a few hours after supper to let go of thoughts that were going to haunt his sleep a second night. It was one of those days he wanted to tell Barb to get on the plane, fly in here, just twenty-four human hours…

With lethal wires on his bedroom doors?

He took out his mail-slot key, he reached for the door, and Jago caught his arm. “The attendant can get it.”

From behind the wall, she meant—because someone was trying to kill him, and Jago didn’t want him reaching into the box after the mail.

“That’s extreme,” he said.

“So might your enemies be.”

“I thought the word was finesse. Blowing up a mail slot?”

“Or inserting a needle in a piece of mail.” She took his key and pocketed it. “The paidhi’s mail, nadi-ji.”

The attendant went. And came back.

“Nothing,” the attendant said.

“There’s always something,” Bren said. “Forgive my persistence, nadi, but my mailbox is never empty. It’s never in my tenure here been empty. Please be sure.”

“I couldn’t mistake you, nand’ paidhi.” The attendant spread his hands. “I’ve never seen the box empty either. Perhaps there’s holiday.”

“Not on any recent date.”

“Perhaps someone picked it up for you.”

“Not by my authorization.”

“I’m sorry, nand’ paidhi. There’s just nothing there.”

“Thank you.” He bowed, there being nothing else to say, and nowhere else to look. “Thank you for your trouble.” And quietly to Jago, in perplexity and distress: “Someone’s been at my mail.”

“Banichi probably picked it up.”

“It’s very kind of him to take the trouble, Jago, but I can pick up my mail.”

“Perhaps he thought to save you bother.”

He sighed and shook his head, and walked away, Jago right with him, from the first step down the hall. “His office, do you think?”

“I don’t think he’s there. He said something about a meeting.”

“He’s taken my mail to a meeting.”

“Possibly, nadi Bren.”

Maybe Banichi would bring it to the room. Then he could read himself to sleep, or write letters, before he forgot human language. Failing that, maybe there’d be a machimi play on television. A little revenge, a little humor, light entertainment.

They took the back halls to reach the main lower corridor, walked to his room. He used his key—opened the door and saw his bed relocated to the other end of the room. The television was sitting where his bed had been. Everything felt wrong-handed.

He avoided the downed wire, dead though it was supposed to be. Jago stepped over it too, and went into his bathroom without a please or may I? and went all around the room with a bug-finder.

He picked up the remote and turned on the television. Changed channels. The news channel was off the air. All the general channels were off the air. The weather channel worked. One entertainment channel did.

“Half the channels are off.”

Jago looked at him, bent over, examining the box that held one end of the wire. “The storm last night, perhaps.”

“They were working this morning.”

“I don’t know, nadi Bren. Maybe they’re doing repairs.”

He flung the remote down on the bed. “We have a saying. One of those days.”

“What, one of those days?”

“When nothing works.”

“A day now or a day to come?” Jago was rightside up now. Atevi verbs had necessary time-distinctions. Banichi spoke a little Mosphei’. Jago was a little more language-bound.

“Nadi Jago. Whatare you looking for?”

“The entry counter.”

“It counts entries.”

“In a very special way, nadi Bren. If it should be a professional, one can’t suppose there aren’t countermeasures.”

“It won’t be any professional. They’re required to file. Aren’t they?”

“People are required to behave well. Do they always? We have to assume the extreme.”

One could expect the aiji’s assassins to be thorough, and to take precautions no one else would take—simply because they knew the utmost possibilities of their trade. He should be glad, he told himself, that he had them looking out for him.

God, he hopednobody broke in tonight. He didn’t want to wake up and find some body burning on his carpet.

He didn’t want to find himself shot or knifed in his bed, either. An ateva who’d made one attempt undetected might lose his nerve and desist. If he was a professional, his employer, losing his nerve, might recall him.

Might.

You didn’t count on it. You didn’t ever quite count on it—you could just get a little easier as the days passed and hope the bastard wasn’t just awaiting a better window of opportunity.

“A professional would have made it good,” he said to Jago.

“We don’t lose many that we track,” Jago said.

“It was raining.”

“All the same,” Jago said.

He wished she hadn’t said that.

Banichi came back at supper, arrived with two new servants, and a cart with three suppers. Algini and Tano, Banichi called the pair, in introduction. Algini and Tano bowed with that degree of coolness that said they were high hall servants, thank you, and accustomed to fancier apartments.

“I trusted Taigi and Moni,” Bren muttered, after the servants had left the cart.

“Algini and Tano have clearances,” Banichi said.

“Clearances.—Did you get my mail? Someone got my mail.”

“I left it at the office. Forgive me.”

He could ask Banichi to go back after it. He could insist that Banichi go back after it. But Banichi’s supper would be cold—Banichi having invited himself and Jago to supper in his apartment.

He sighed and fetched an extra chair. Jago brought another from the side of the room. Banichi set up the leaves of the serving table and set out the dishes, mostly cooked fruit, heavily spiced, game from the reserve at Nanjiran. Atevi didn’t keep animals for slaughter, not the Ragi atevi, at any rate. Mospheira traded with the tropics, with the Nisebi, down south, for processed meat, preserved meat, which didn’t have to be sliced thin enough to admit daylight—a commerce which Tabini-aiji called disgraceful, and which Bren had reluctantly promised to try to discourage, the paidhi being obliged to exert bidirectional influence, although without any veto power over human habits.

So even on Mospheira it wasn’t politic for the paidhi to eat anything but game, and that in appropriate season. To preserve meat was commercial, and commercialism regarding an animal life taken was not kabiu, not ‘in the spirit of good example.’ The aiji’s household had to be kabiu. Very kabiu.

And observing this point of refinement was, Tabini had pointed out to him with particular satisfaction in turning the tables, ecologicallysound harvesting practice. Which the paidhi must, of course, support with the same enthusiasm when it came from atevi.

Down in the city market you could get a choice of meats. Frozen, canned, and air-dried.

“Aren’t you hungry, nadi?”

“Not my favorite season.” He was graceless this evening. And unhappy. “Nobody knows anything. Nobody tells me anything. I appreciate the aiji’s concern. And yours. But is there some particular reason I can’t fly home for a day or two?”

‘The aiji—“

“Needs me. But no one knows why. You wouldn’t mislead me, would you, Jago?”

“It’s my profession, nadi Bren.”

“To lie to me.”

There was an awkward silence at the table. He’d intended his bluntness as bitter humor. It had come out at the wrong moment, into the wrong mood, into their honest and probably frustrated efforts to find answers. Of all humans, he was educated not to make mistakes with them.

“Forgive me,” he said,

“His culture will lie,” Banichi said plainly to Jago. “But admitting one has done so insults the victim.”

Jago took on a puzzled look.

“Forgive me,” Bren said again. “It was a joke, nadi Jago.”

Jago still looked puzzled, and frowned, but not angrily. “We take this threat very seriously.”

“I didn’t. I’m beginning to.” He thought: Where’s my mail, Banichi? But he had a mouthful of soup instead. Making too much haste with atevi was not, notproductive. “I’m grateful. I’m sure you had other plans this evening.”

“No,” said Jago.

“Still,” he said, wondering if they’d fixed the television outage yet, and what he was going to say to Banichi and Jago for small talk for the rest of the evening. Maybe there was a play on the entertainment channel. It seemed they might stay the night.

And in whose bed would they sleep, he asked himself.—Or would they sleep? They didn’t show the effects of last night at all.

“Do you play cards?”

“Cards?” Jago asked, and Banichi shoved his chair back and said he should teach her.

“What are cards?” Jago asked, when what Bren wanted to ask Banichi involved his mail. But Banichi probably had far more important things on his mind—like checking with security, and being sure surveillance items were working.

“It’s a numerical game,” Bren said, wishing Banichi wasn’t deserting him to Jago—he hoped not for the night. When are you leaving? wasn’t a politic question. He was still trying to figure how to ask it of Banichi, or what he should say if Banichi said Jago was staying… when Banichi went out the door, with, “Mind the wire, nadi Bren.”

“Gin,” Jago said.

Bren sighed, laid his cards down, glad there wasn’t money involved.

“Forgive me,” Jago said. “You said I should say that. Unseemly gloating was far from—”

“No, no, no. It’s entirely the custom.”

“One isn’t sure,” Jago said. “Am I to be sure?”

He had embarrassed Jago. He had been mishidi—awkward. He held out his palm, the gesture of conciliation. “You’re to be sure.” God, one couldn’t walk without tripping over sensitivities. “It’s actually courteous to tell me you’ve won.”

“You don’t count the cards?”

Atevi memory was, especially regarding numbers, hard to shake, no matter that Jago was not the fanatic number-adder you found in the surrounding city. And no, he hadn’t adequately counted the cards. Neverplay numbers with an atevi.

“I would perhaps have done better, nadi Jago, if I weren’t distracted by the situation. I’m afraid it’s a little more personal to me.”

“I assure you we’ve staked our personal reputations on your safety. We’d never be less than committed to our effort.”

He had the impulse to rest his head on his hand and resign the whole conversation. Jago would take that as evidence of offense, too.

“I wouldn’t expect otherwise, nadi Jago, and it’s not your capacity I doubt, not in the least. I could only wish my own faculties were operating at their fullest, or I should not have embarrassed myself just now, by seeming to doubt you.”

“I’m very sorry.”

“I’ll be far brighter when I’ve slept. Please regard my mistakes as confusion.”

Jago’s flat black face and vivid yellow eyes held more intense expression than they were wont—not offense, he thought, but curiosity.

“I confess myself uneasy,” she said, brow furrowed. “You declare absolutely you aren’t offended.”

“No.” One rarely touched atevi. But her manner invited it. He patted her hand where it rested on the table. “I understand you.” It seemed not quite to carry the point, and, looking her in the eyes, he flung his honest thoughts after it. “I wish you understood me on this. It’s a human thought.”

“Are you able to explain?”

She wasn’t asking Bren Cameron: she didn’t know Bren Cameron. She was asking the paidhi, the interpreter to her people. That was all she coulddo, Bren thought, regarding the individual she was assigned by the aiji to protect, since the incident last night—an individual who didn’t seem in her eyes to take the threat seriously enough, or to take her seriously… and how was she to know anything about him? How was she to guess, with the paidhi giving her erratic clues? Will you explain? she asked, when he wished aloud that she understood him.

“If it were easy,” he said, trying with all his wits to make sense of it to her—or to divert her thinking away from it, “there wouldn’t need to be a paidhi at all.—But I wouldn’t be human, then, and you wouldn’t be atevi, and nobody would need me anyway, would they?”

It didn’t explain anything at all. He only tried to make the confusion less important than it was. Jago could surely read that much. She worried about it and thought about it. He could see it in her eyes.

“Where’s Banichi gone?” he asked, feeling things between them slipping further and further from his control. “Is he planning to come back here tonight?”

“I don’t know,” she said, still frowning. Then he decided, in the convolutions of his exhausted and increasingly disjointed thoughts, that even thatmight have sounded as if he wanted Banichi instead of her.

Which he did. But not for any reason of her incompetency. Dealing with a shopkeeper with a distrust of computers was one thing. He was not faring well at all in dealing with Jago, he could not put out of his mind Banichi’s advisement that she liked his hair, and he decided on distraction.

“I want my mail.”

“I can call him and ask him to bring it.”

He had forgotten about the pocket-com. “Please do that,” he said, and Jago tried.

And tried. “I can’t reach him,” Jago said.

“Is he all right?” The matter of the mail diminished in importance, but not, he feared, in significance. Too much had gone on that wasn’t ordinary.

“I’m sure he is.” Jago gathered up the cards. “Do you want to play again?”

“What if someone broke in here and you needed help? Where do you suppose he is?”

Jago’s broad nostrils flared, “I have resources, nadi Bren.”

He couldn’t keepfrom offending her.

“Or what if hewas in trouble? What if they ambushed him in the halls? We might not know.”

“You’re very full of worries tonight.”

He was. He was drowning in what was atevi; and that failure to understand, in a sudden moment of panic, led him to doubt his own fitness to be where he was. It made him wonder whether the lack of perception he had shown with Jago had been far more general, all along—if it had not, with some person, led to the threat he was under.

Or, on the other hand, whether he was letting himself be spooked by his guards’ zealousness because of some threat of a threat that would never, ever rematerialize.

“Worries about what, paidhi?”

He blinked, and looked by accident up into Jago’s yellow, unflinching gaze. Don’t you know? he thought. Is it a challenge, that question? Is it distrust of me? Why these questions?

But you couldn’t quite say ‘trust’ in Jago’s language, either, not in the terms a human understood. Every house, every province, belonged to a dozen associations, that made webs of association all through the country, whose border provinces made associations across the putative borders into the neighbor associations, an endless fuzzy interlink of boundaries that weren’t boundaries, both geographical and interest-defined—‘trust,’ would you say? Say man’chi– ‘central association,’ the one association that defined a specific individual.

“ Man’china aijiia nai’am,” he said, to which Jago blinked a third time. I’m the aiji’s associate, foremost. “ Nai’danei man’chini somai Banichi?” Whose associate are you and Banichi, foremost of all?

“ Tabini-aijiia, hei.” But atevi would lie to anyone but their central associate.