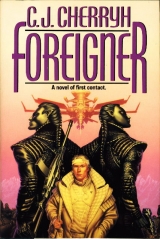

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

XIV

« ^ »

Not doing well, he wasn’t—with one pain shooting through his eyes and another running through his elbow to the pit of his stomach, while two or three other point-sources contested for his attention. The rain had whipped up to momentary thunder and a fit of deluge, then subsided to wind-borne drizzles, a cold mist so thick one breathed it. The sky was a boiling gray, while the mecheiti struck a steady, long-striding pace one behind the other, Babs leading the way up and down the rain-shadowed narrows, along brushy stretches of streamside, where frondy ironheart trailed into their path and dripped water on their heads and down their necks.

But there wasn’t the same jostling for the lead, now, among the foremost mecheiti. It seemed it wasn’t just Nokhada, after all. None of them were fighting, whether Ilisidi had somehow communicated that through Babs, or whether somehow, after the bombs, and in the misery of the cold rain, even the mecheiti understood a common urgency. The established order of going had Nokhada fourth in line behind another of Ilisidi’s guards.

One, two, three, four, regular as a heartbeat, pace, pace, pace, pace.

Never betray you. Hell.

More tea? Cenedi asked him.

And sent him to the cellar.

His eyes watered with the throbbing in his skull and with the wind blasting into his face, and the desire to beat Cenedi’s head against a rock grew totally absorbing for a while. But it didn’t answer the questions, and it didn’t get him back to Mospheira.

Just to some damned place where Ilisidi had friends.

Another alarm bell, he thought. Friends. Atevi didn’t have friends. Atevi had man’chi, and hadn’t someone said—he thought it was Cenedi himself—that Ilisidi hadn’t man’chito anyone?

They crossed no roads—with not a phone line, not a tilled field, not the remote sound of a motor, only the regular thump of the mecheiti’s gait on wet ground, the creak of harness, even, harsh breathing—it hypnotized, mile after rain-drenched and indistinguishable mile. The dwindling day had a lucent, gray sameness. Sunlight spread through the clouds no matter what the sun’s angle with the hills.

Ilisidi reined back finally in a flat space and with a grimace and a resettling on Babs’ back, ordered the four heavier men to trade off to the unridden mecheiti.

That included Cenedi; and Banichi, who complained and elected to do it by leaning from one mecheita to the other, as only one of the other men did—as if Banichi and mecheiti weren’t at all unacquainted.

Didn’t hurt himself. Expecting that event, Bren watched with his lip between his teeth until Banichi had straightened himself around.

He caught Jago’s eye then and saw a biding coldness, total lack of expression—directed at him.

Because human and atevi hormones were running the machinery, now, he told himself, and the lump he had in his throat and the thump of emotion he had when he reacted to Jago’s cold disdain composed the surest prescription for disaster he could think of.

Shut it down, he told himself. Do the job. Think it through.

Jago didn’t come closer. The whole column sorted itself out in the prior order, and Nokhada’s first jerking steps carried him out of view.

When he looked back, Banichi was riding as he had been, hands braced against the mecheita’s shoulders, head bowed—Banichi was suffering, acutely, and he didn’t know whether the one of their company who seemed to be a medic, and who’d had a first aid kit, had also had a pain-killer, or whether Banichi had taken one or not, but a broken ankle, splinted or not. had to be swelling, dangling as it was, out of the stirrup on that side.

Banichi’s condition persuaded him that his own aches and pains were ignorable. And it frightened him, what they might run into and what, with Banichi crippled, and with Ilisidi willing to leave him once, they coulddo if they met trouble at the end of the ride–if Wigairiin wasn’t in allied hands.

Or if Ilisidi hadn’t told the truth about her intentions—because it occurred to him she’d said no to the rebels in Maidingi, but she’d equally well been conspiring with Wigairiin, evidently, as he picked it up, as an old associate only apt to come in with the rebels if Ilisidi did.

That meant queasy relationships and queasy alliances, fragile ties that could do anything under stress.

In the cellar, they’d recorded his answers to their questions—they saidit was all machimi, all play-acting, no validity.

But that tape still existed, if Ilisidi hadn’t destroyed it. She’d not have left it behind in Malguri, for the people that were supposedly her jilted allies.

If Ilisidi hadn’t destroyed it—they had that tape, and they had it with them.

He reined back, disturbing the column. He feigned a difficulty with the stirrup, and stayed bent over as rider after rider passed him at that rapid, single-minded pace.

He let up on the rein when Banichi passed him, and the hindmost guards had pulled back, too, moving in on him. “Banichi, there’s a tape recording,” he said. “Of me. Interrogation about the gun.”

At which point he gave Nokhada a thump of his heel and slipped past the guards, as Nokhada quickened pace.

Nokhada butted the fourth raecheita in the rump as she arrived, not gently, with the war-brass, and the other man had to pull in hard to prevent a fight.

“Forgive me, nadi,” Bren said breathlessly, heart thumping. “I had my stirrup twisted.”

It was still a near fight. It helped Nokhada’s flagging spirits immensely, even if she didn’t get the spot in line.

It didn’t at all help his headache, or the hurt in his arm, half of it now. he thought, from Nokhada’s war for the rein.

The gray daylight slid subtly into night, a gradual dimming to a twilight of wind-driven rain, a ghostly half-light that slipped by eye-tricking degrees into blackest, starless night. He had thought they would have to slow down when night fell—but atevi eyes could deal with the dark, and maybe mecheiti could: Babs kept that steady, ground-devouring pace, laboring only when they had to climb, never breaking into exuberance or lagging on the lower places; and Nokhada made occasional sallies forward, complaining with tosses of her head and jolts in her gait when the third-rank mecheita cut her off, one constant, nightmare battle just to keep control of the creature, to keep his ears attuned for the whisper of leaves ahead that forewarned him to duck some branch the first riders had ducked beneath in the dark.

The rain must have stopped for some while before he even noticed, there was so much water dripping and blowing from the leaves generally above them.

But when they broke out into the clear, the clouds had gone from overhead, affording a panorama of stars and shadowy hills that should have relieved his sense of claustrophobic dark—but all he could think of was the ship presence that threatened the world and the fact that, if they didn’t reach this airstrip by dawn, they’d be naked to attack from Maidingi Airport.

By midnight, Ilisidi had said, they’d reach Wigairiin, and that hour was long since past, if he could still read the pole stars.

Only let me die, he began to think, exhausted and in pain, when they began to climb again, and climb, and climb the stony hill. Ilisidi called a halt, and he supposed that they were going to trade off again, and that it meant they’d as long to go as they’d already ridden.

But he saw the ragged edge of ironheart against the night sky above them on the hill, and Ilisidi said they should all get down, they’d gone as far as the mecheiti would take them.

Then he wished they had a deal more of riding to go, because it suddenly dawned on him that all bets were called. They were committing themselves, now, to a course in which neither Banichi nor Jago was going to object, not after Banichi had argued vainly against it at the outset. God, he was scared of this next part.

Banichi didn’t have any help but him—not even Jago, so far as he could tell. He had the computer to manage… his last chance to send it away with Nokhada and hope, hopethe handlers, loyal to Ilisidi, would keep it from rebel attention.

But if rebels did hold Malguri now, they’d be very interested when the mecheiti came in—granted anything had gone wrong and they didn’t get a fast flight out of here, the computer was guaranteed close attention. And things could go wrong, very wrong.

Baji-naji. Leaving it for anyone else was asking too much of Fortune and relying far too much on Chance. He jerked the ties that held the bags on behind the riding-pad, gathered them up as the most ordinary, the most casual thing in the world, his hands trembling the while, and slid off, gripping the mounting-straps to steady his shaking knees.

Breath came short. He leaned on Nokhada’s hard, warm shoulder and blacked out a moment, felt the chill of the cellar about him, the cords holding him. Heard the footsteps—

He tried to lift the bags to his shoulder.

A hand met his and took them away from him. “It’s no weight for me,” the man said, and he stood there stupidly, locked between believing in a compassion atevi didn’t have and fearing the canniness that might well have Cenedi behind it—he didn’t know, he couldn’t think, he didn’t want to make an issue about it, when it was even remotely possible they didn’t even realize he had the machine with him. Djinana had brought it. The handlers had loaded it.

The man walked off. Nokhada brushed him aside and wandered off across the hill in a general movement of the mecheiti: a man among Ilisidi’s guard had gotten onto Babs and started away as the whole company began to move out, afoot now, presumably toward the wall Ilisidi had foretold, where, please God, the gate would be open, the way Ilisidi had said, nothing would be complicated and they could all board the plane that would carry them straight to Shejidan.

The man who’d taken the bags outpaced him with long, sure strides up the hill in the dark, up where Cenedi and Ilisidi were walking, which only confirmed his worst suspicions, and he needed to keep that man in sight—he needed to advise Banichi what was going on, but Banichi was leaning on Jago and on another man, further down the slope, falling behind.

He didn’t know which to go to, then—he couldn’t get a private word with Banichi, he couldn’t keep up with both. He settled for limping along halfway between the two groups, damning himself for not being quicker with an answer that would have stopped the man from taking the saddlebags and not coming up with anything now that would advise Banichi what was in that bag without advising the guard with him—as good as shout it aloud, as say anything to Banichi now.

Claim he needed something from his personal kit?

It might work. He worked forward, out of breath, the hill going indistinct on him by turns.

“Nadi,” he began to say.

But as he came up on the man, he saw the promised wall in front of them, at the very crest of the hill. The ancient gate was open on a starlit, weed-grown road.

They were already atWigairiin.

XV

« ^ »

The wall was a darkness, the gate looked as if it could never again move on its hinges.

The shadows of Ilisidi and Cenedi went among the first into an area of weeds and ancient cobblestones, of old buildings, a road like the ceremonial road of the Bu-javid, maybe of the same pre-Ragi origin—the mind came up with the most irrational, fantastical wanderings, Bren thought, desperately tagging the one of Ilisidi’s guards who had his baggage, and his computer.

Banichi and Jago were behind him somewhere. The ones in front were going in as much haste as Ilisidi could manage, using her cane and Cenedi’s assistance, which could be quite brisk when Ilisidi decided to move, and she had.

“I can take it now, nadi,” Bren said, trying to liberate the strap of his baggage from the man’s shoulder much as the man had gotten it away from him. “It’s no great difficulty. I need something from the kit.”

“No time now to look for anything, nand’ paidhi,” the man said. “Just stay up with us. Please.”

It was damned ridiculous. He lost a step, totally off his balance, and then grew angry and desperate, which didn’t at all inform him what was reasonable to do. Stick close to the man, raise no more issue about the bags until they stopped, try to claim there was medication he had to have as soon as they got to the plane and then stow the thing under his seat, out of view… that was the only plan he could come up with, trudging along with aches in every bone he owned and a headache that wasn’t improving with exertion.

They met stairs, open-air, overgrown with weeds, where the walk began to pass between evidently abandoned buildings. That went more slowly—Ilisidi didn’t deal well with steps; and one of the younger guards simply picked her up after a few steps and carried her in his arms.

Which with Banichi wasn’t an option. Bren looked back, lagged behind, and one of the guards near him took his arm and pulled him along, saying,

“Keep with us, nand’ paidhi, do you need help?”

“No,” he said, and started to say, Banichi does.

Something banged. A shot hit the man he was talking to, who staggered against the wall. Shots kept coming, racketing and ricocheting off the walls beside the walk, as the man, holding his side, jerked him into cover in a doorway and shoved his head down as gunfire broke out from every quarter.

“We’ve got to get out of here,” Bren gasped, but the guard with him slumped down and the fire kept up. He tried in the dark and by touch to find where the man was hit—he felt a bloody spot, and tried for a pulse, and couldn’t find it. The man had a limpness he’d never felt in a body—dead, he told himself, shaking, while the fire bounced off walls and he couldn’t tell where it was coming from, or even which side of it was his.

Banichi and Jago had been coming up the steps. The man lying inert against his knee had pulled him into a protected nook that seemed to go back among the weeds, and he thought it might be a way around and down the hill that didn’t involve going out onto the walk again.

He let the man slide as he got up, made a foolish attempt to cushion the man’s head as he slid down, and in agitation got up into a crouch and felt his way along the wall, scared, not knowing where Ilisidi and Cenedi had gone or whether it was Tabini’s men or the rebels or what.

He kept going as far as the wall did, and it turned a corner and went downhill a good fifty or so feet before it met another wall, in a pile of old leaves. He retreated, and met still another when he tried in the other direction.

The gunfire stopped, then. Everything stopped. He sank down with his shoulders against the wall of the cul de sac and listened, trying to still his own ragged breaths and stop shaking.

It grew so still he could hear the wind moving the leaves about in the ruins.

What isthis place? he asked himself, seeing nothing when he looked back down the alleyway but a lucent slice of night sky, starlight on old brick and weeds, and a section of the walk. He listened and listened, and asked himself what kind of place Ilisidi had directed them into, and why Banichi and Jago didn’t realize the place was an ancient ruin. It felt as if he’d fallen into a hole in time—a personal one, in which he couldn’t hear the movements he thought he should hear, just his own occasional gasps for breath and a leaf skittering down the pavings.

No sound of a plane.

No sound of anyone moving.

They couldn’t all be dead. They had to be hiding, the way he was. If he went on moving in this quiet, somebody might hear him, and he couldn’t reason out who’d laid the ambush—only it seemed likeliest that if they’d just opened fire, they didn’t care if they killed the paidhi, and thatsounded like the people out of Maidingi Airport who’d lately been dropping bombs.

So Ilisidi and Cenedi were wrong, and Banichi was right, and their enemies had gotten into the airport here, if there truly was an airport here at all.

Nobody was moving anywhere right now. Which could mean a lot of casualties, or it could mean that everybody was sitting still and waiting for the other side to move first, so they could hear where they were.

Atevi saw in the dark better than humans. To atevi eyes, there was a lot of light in the alley, if somebody looked down this way.

He rolled onto his hands and a knee, got up and went as quietly as he could back into the dead end of the alley, sat down again and tried to think—because if he could get to Banichi, or Cenedi, or any of the guards, granted these were Ilisidi’s enemies no less than his—there was a chance of somebody knowing where he was going, which he didn’t; and having a gun, which he didn’t; and having the military skills to get them out of this, which he didn’t.

If he tried downhill, to go back into the woods—but they were fools if they weren’t watching the gate.

If he could possibly escape out into the countryside… there was the township they’d mentioned, Fagioni—but there was no way he could pass for atevi, and Cenedi or Ilisidi, one or the other, had said Fagioni wouldn’t be safe if the rebels had Wigairiin.

He could try to live off the land and just go until he got to a politically solid border—but it had been no few years since botany, and he gave himself two to three samples before he mistook something and poisoned himself.

Still, if there wasn’t a better chance, it was a chance—a man could live without food, as long as there was water to drink, a chance he was prepared to take, but—atevi night-vision being that much better, and atevi hearing being quite acute—a move now seemed extremely risky.

More, Banichi must have seen him ahead of him on the steps, and if Banichi and Jago were still alive… there was a remote hope of them locating him. He was, he had to suppose, a priority for everyone, the ones he wanted to find him and the ones he most assuredly didn’t.

His own priority… unfortunately… no one served. He’d lost the computer. He had no idea where the man with his baggage had gone, or whether he was alive or dead; and he couldn’t go searching out there. Damned mess, he said to himself, and hugged his arms about him beneath the heat-retaining rain-cloak, which didn’t help much at all where his body met the rain-chilled bricks and paving.

Damned mess, and at no point had the paidhi been anything but a liability to Ilisidi, and to Tabini.

The paidhi was sitting freezing his rump in a dead-end alley, where he had no way to maneuver if he heard a search coming, no place to hide, and a systematic search was certainly going to find him, if he didn’t do something like work back down the hill where he’d last seen Banichi and Jago, and where the gate was surely guarded by one side or the other.

He couldn’t fight an ateva hand to hand. Maybe he might find a loose brick.

If—He heard someone moving. He sat and breathed quietly, until after several seconds the sound stopped.

He wrapped the cloak about him to prevent the plastic rustling. Then, one hand braced on the wall to avoid a scuff of cold-numbed feet, he gathered himself up and went as quickly and quietly as his stiff legs would carry him, in the only direction the alley afforded him.

He reached the guard’s body, where it lay at the entry to the alley, touched him to be sure beyond a doubt he hadn’t left a wounded man, and the man was already cold.

That was the company he had, there in the entry where old masonry made a nook where a human could squeeze in and hide, and a crack through which he could see the walk outside, through a scraggle of weeds.

Came the least small sound of movement somewhere, up or down the hill, he wasn’t sure. He found himself short of breath, tried to keep absolutely still.

He saw a man then, through the crack, a man with a gun, searching the sides and the length of the walk—a man without a rain-cloak, in a different jacket than anyone in Cenedi’s company.

One of the opposition, for certain. Looking down every alley. And coming to his.

He drew a deep, deep breath, leaned his head back against the masonry and turned his face into the shadow, tucked his pale hands under his arms. He heard the steps come very close, stop, almost within the reach of his arm. He guessed that the searcher was examining the guard’s body.

God, the guard was armed. He hadn’t even thought about it. He heard a soft movement, a click, from where the searcher was examining the body. He daren’t risk turning his head. He stayed utterly still, until finally the searcher went all the way down the alley. A flashlight flared on the walls down at the dead end, where he had recently hidden. He stayed still and tried not to shiver in his narrow concealment while the man walked back again, this time using the flashlight.

The beam stopped short of him. The searcher cut the flashlight off again, perhaps fearing snipers, and, stepping over the guard’s body, went his way down the hill.

Mopping up, he thought, drawing ragged breaths. When he was as sure as he could make himself that the search had passed him, he got down and searched the dead guard for weapons.

The holster was empty. There was no gun in either hand, nor under the body.

Damn, he thought. He didn’t naturally thinkin terms of weapons, they weren’t his ordinary resort, and he’d made a foolish and perhaps a fatal mistake—he was up against professionals, and he was probably still making mistakes, like in being in this dead end alley and not thinking about the gun before the searcher picked it up; they were doing everything right and he was doing everything wrong, so far, except they hadn’t caught him.

He didn’t know where to go, had no concept of the place, just of where he’d been, but he’d be wise, he decided, at least to get out of the cul de sac; and following the search seemed better than being in front of it.

He got up, wrapped the cloak about him to be as dark as he could, and started out.

But the same instant he heard voices down the street and ducked back into his nook, heart pounding.

He didn’t know where the solitary searcher had gone. He grew uncertain what was going on out there now—whether the search might have turned back, or changed objectives. He didn’t know what a professional like Banichi might know or expect: having no skill at stealth, he decided the only possible advantage he could make for himself was patience, simply outlasting them in staying still in a concealment one close search hadn’t penetrated. They hadn’t night-scopes, none of the technology humans had known without question atevi would immediately apply to weaponry. They didn’t use any tracking animals, except mecheiti, and he hoped there were no mecheiti on the other side. He’d seen one man ripped up.

He stood in shadow while the searchers passed, also bound downhill, and while they, too, checked over the dead man almost at his feet, and likewise sent a man down to look through the alley to the end. They talked together in low voices, some of it too faint to hear, but they talked about a count on their enemies, and agreed that this was the third sure kill.

They went away, then, down the hill, toward the gate.

A long while later he heard a commotion from that quarter, a calling out of instructions, by the tone of it. The voices stopped; the movements went on for some time, and eventually he saw other men, not their own, walking down toward the gate.

That way of escape was shut, then. There wasn’ta way out the gate. If any of their party was alive, they weren’t going to linger down there, he could reason that. The force was concentrating behind him for a sweep forward, and he visualized what he in his untrained and native intelligence would do—hold that gate shut until morning and scour the area inside the gate by daylight.

He took a breath, looked through the screen of weeds growing in the chinks in the wall near his head, and ducked out again onto the walk, wrapped in his plastic cloak and aiming immediately for the next best cover, a nook further on.

He found another alley. He took it, trying to find somewhere in it a small dark hole that a searcher might not automatically think to look into even in a daylight search. He could fit where adult atevi wouldn’t fit. He could squeeze into places searchers couldn’t follow and might not realize a human could fit.

He followed the alley around two turns, feared it might dead-end like the other one, then saw open space ahead—saw flat ground, blue lights, and a hill, and a great house sprawling up and up that hill, with its own wall, and white lights showing.

Wigairiin, he said to himself, and saw the jet down at the end of the runway, sitting in shadow, its windows dark, its engines silent.

Ilisidi hadn’t lied, then. Cenedi hadn’t. There was a plane and it had waited for them. But something had gone terribly wrong, the enemy had moved in, taken Wigairiin the way Banichi had warned them they might. Banichi had been right and no one had listened, and he was here, in the mess he was in.

Banichi had said Tabini would move against the rebels—but there was that ship up in the heavens, and Tabini couldn’t talk to Mospheira unless they’d sent Hanks, and, damn the woman. Hanks wasn’t going to be helpful to an aiji fighting to solidify his support, to a population dissolving uneasy associations and lesser aijiin trying to position themselves to survive the fall of the aiji in Shejidan. Hanks had outright saidto him that the country assocations didn’t matter, he’d argued otherwise, and Hanks had refused to understand why he adamantly took the position that they did.

All around him was the evidence that they did.

And Ilisidi and Cenedi hadn’tlied to him. The plane existed—no one had lied, after all, not their fault the rebels had figured their plan. It got to his gut that, at least that far, the atevi he was with hadn’t betrayed him. Ilisidi had possibly meant all along to go to Shejidan—until something had gone mortally wrong. He leaned against the wall with a knot in his throat, light-headed, and trying to reason, all the same, it didn’t mean they didn’t mean to go somewhere else, but after hours convinced they were being dragged into a trap, knowing at least that the trap closing around him was not the doing of people he’d felt friendly…

Felt friendly, felt, friendly… Two words the paidhi didn’t use, but the paidhi was clearly over the edge of personal andprofessional judgment. He wiped at his eyes with a shaking hand, ventured as carefully as he knew along the frontage of abandoned buildings, among weeds and past old machinery, still looking for that place to hide, with no idea how long he might have to hold out, not knowing how long he could hold out, against the hope of Tabini taking Maidingi and moving forces in to Wigairiin along the same route they’d come.

Give or take a few days, a few weeks, it might happen, if he could stay free. Rainy season. He wouldn’t die of thirst, hiding out in the ruins. A man could go unfed for a week or so, just not move much. He just needed a place—any place, but best one where he might have some view of what came and went.

He saw old tanks of some kind ahead, facing the field, oil or jet fuel or something, he wasn’t sure, but the ground was grown up with weeds and they didn’t look used. They offered a place, maybe, to hide in the shadows where they met the wall—his enemies might expect him down closer to the gate, not on the edge of the field, watching them, right up in an area where they probably worked…

Another, irrational flash on the cellar. He didn’t see where he was, saw that dusty basement instead and knew he was doing it. He reached out and put his hand on the wall to steady himself—retained presence of mind enough at least to know he should watch his feet, there’d been other kinds of debris around, in a disorder not ordinary for atevi. Old machine parts, old scrap lumber, old building stone, in an area Wigairiin clearly didn’t keep up.

Knocked down an ancient wall to build the airstrip, Ilisidi had said that. Didn’t care much for the old times.

Ilisidi did. Didn’t agree with the aijiin of Wigairiin on that point.

They’d talked about dragonettes, and preserving a national treasure. And the treasure was being blasted with explosives and atevi were killing each other—for fear of humans, in the name of Tabini-aiji, sitting where Ilisidi had worked all her life to be—

Dragonettes soaring down the cliffs.

Atevi antiquities, leveled to build a runway, so a progressive local aiji didn’t have to take a train to Maidingi.

He reached the tanks, felt the rusted metal flake on his hands—blind in the dark, he slid down and squirmed his way into the nook they made with the wall—lay down, then, in the wet weeds underneath the braces.

Wasn’t sure where he was for a moment. He didn’t hurt as much. Couldn’t see that conveniently out of the hole he’d found, just weeds in front of his face. His heart beat so heavily it jarred the bones of his chest. He’d never felt it do that. Didn’t hurt, exactly, nothing did, more than the rest of him. Cold on one side, not on the other, thanks to the rain-cloak.

He’d found cover. He didn’t have to move from here. He could shut his eyes.

He didn’t have to think, either, just rest, let the aches go numb.

He wished he’d done better than he’d done.

Didn’t know how he could have. He was alive and they hadn’t found him. Better than some of the professionals had scored. Better luck than poor Giri, who’d been a decent man.

Better luck than the man who’d dragged him to cover before he died—the man hadn’t thought about it, he supposed; he’d just done, just moved. He supposed it made most difference what a man was primed to do. Call it love. Call it duty. Call it—whatever mecheiti did, when the bombs fell around them and they still followed the mecheit’-aiji.

Man’chi. Didn’t mean duty. That was the translation on the books. But what had made the man grab him with the last thought he had—that was man’chi, too. The compulsion. The drive that held the company together.

They said Ilisidi hadn’t any. That aijiin didn’t. Cosmic loneliness. Absolute freedom. Babs. Ilisidi. Tabini.