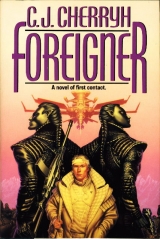

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

“I’m not a cursed dinner-course!”

“Banichi-ji.” The pain reached a level and stayed there, tolerable, once he’d discovered the limits of it. He had his hand on the stonework. He felt the texture of it, the silken dust of age, the fire-heated rock, broken from the earth to make this building before humans ever left the home-world. Before they were ever lost, and desperate. He composed himself—he remembered he was the paidhi, the man in the middle. He remembered he’d chosen this, knowing there wouldn’t be a reward, believing, at the time, that of course atevi had feelings, and of course, once he could find the right words, hit the right button, findthe clue to atevi thought—he’d win of atevi everything he was giving up among humankind.

He’d been twenty-two, and what he’d not known had so vastly outweighed what he’d known.

“Your behavior worries me,” Banichi said.

“Forgive me.” There was a large knot interfering with his speech. But he was vastly calmer. He chose not to look at Banichi. He only imagined the suspicion and the anger on Banichi’s face. “I reacted unprofessionally and intrusively.”

“Reacted to what, nand’ paidhi?”

A betraying word choice. He wasslipping, badly. The headache had upset his stomach, which was still uncertain. “I misinterpreted your behavior. The mistake was mine, not yours. Will you attend my appointment with me in the morning, and guard me from my own stupidity?”

“What behavior did you misinterpret?”

Straight back to the attack. Banichi refused the bait he cast. And he had no ability to argue, now, or to deal at all in cold rationality.

“I explained that. It didn’t make sense to you. It won’t.” He stared into the hazy corners beyond the firelight, and remembered the interpretation Banichi had put on his explanation. “It wasn’t a threat, Banichi. I would never do that. I value your presence and your good qualities. Will you go with me tomorrow?”

Back to the simplest, the earliest and most agreed-upon words. Cold. Unfreighted.

“No, nadi. No one invites himself to the dowager’s table. You accepted.”

“You’re assigned—”

“My man’chiis to Tabini. My actions are his actions. The paidhi can’t have forgotten this simple thing.”

He was angry. He looked at Banichi, and went on looking, long enough, he hoped, for Banichi to think in what other regard his actions were Tabini’s actions. “I haven’t forgotten. How could I forget?”

Banichi returned a sullen stare. “Ask regarding the food you’re offered. Be sure the cook understands you’re in the party.”

The door in the outermost room opened. Banichi’s attention was instant and wary. But it was Jago coming through, rain-spattered as Banichi, in evident good humor until the moment she saw the two of them. Her face went immediately impassive. She walked through to his bedroom without comment.

“Excuse me,” Banichi said darkly, and went after her.

Bren glared at his black-uniformed back, at a briskly swinging braid—the two of Tabini’s guards on their way through his bedroom, to the servant quarters; he hit his fist against the stonework and didn’t feel the pain until he walked away from the fireside.

Stupid, he said to himself. Stupid and dangerous to have tried to explain anything to Banichi: Yes, nadi, no, nadi, clear and simple words, nadi.

Banichi and Jago had gone on to the servants’ quarters, where they lodged, separately. He went through to his own bedroom and undressed, with an eye to the dead and angry creature on the wall, the expression of its last, cornered fight.

It stared back at him, when he was in the bed. He picked up his book and read, because he was too angry to sleep, about ancient atevi battles, about treacheries and murders.

About ghost ships on the lake, and a manifestation that haunted the audience hall on this level, a ghostly beast that sometimes went snuffling up and down the corridors, looking for something or someone.

He was a modern man. They were atevi superstitions. But he took one look and then evaded the glass, glaring eyes of the beast on the wall.

Thunder banged. The lights all went out, except the fire in the next room, casting its uncertain glow, that didn’t reach all the corners of this one, and didn’t at all touch the servants’ hall.

He told himself lightning must have hit a transformer.

But the place was eerily quiet after that, except for a strange, distant thumping that sounded like a heartbeat coming through the walls.

Then far back in the servants’ hall, beyond the bath, steps moved down the corridor toward his bedroom.

He slid off the bed, onto his knees.

“Nand’ paidhi,” Jago’s voice called out. “It’s Jago.”

He withdrew his hand from beneath the mattress, and slithered up onto the bed, sitting and watching as an entire brigade of staff moved like shadows through his room and outward. He couldn’t see faces. He saw the spark of metal on what he thought was Banichi’s uniform.

One lingered.

“Who is it?” he asked, anxiously.

“Jago, nadi. I’m staying with you. Go to sleep.”

“You’re joking!”

“It’s most likely only a lightning strike, nand’ paidi. That’s the auxiliary generator you hear. It keeps the refrigeration running in the kitchen, at least until morning.”

He got up, went looking for his robe and banged his knee on a chair, making an embarrassing scrape.

“What do you want, nadi?”

“My robe.”

“Is this it?” Jago located it instantly, at the foot of his bed, and handed it to him. Atevi night vision was that much better, he reminded himself, and took not quite that much comfort from knowing it. He put the robe on, tied it about him and went into the sitting room, as less provocative, out where the fireplace provided one kind of light and a whiter, intermittent flicker of lightning came from the windows.

A padding, metal-sparked shadow followed him. Atevi eyes reflected a pale gold. Atevi found it spooky that human eyes didn’t, that humans could slip quietly through the dark. Their differences touched each others’ nightmares.

But there was no safer company in the world, he told himself, and told himself also that the disturbance was in fact nothing but a lightning strike, and that Banichi was going to be wet, chilled, and in no good mood when he got back in.

But Jago wasn’t in her night-robe. Jago had been in uniform and armed, and so had Banichi been, when the lights had gone.

“Don’t you sleep?” he asked her, standing before the fire.

The twin reflections of her eyes eclipsed, a blink, then vanished as she came close enough to rest an elbow against the stonework mantel. Her shadow loomed over him, and fire glistened on the blackness of her skin. “We were awake,” she said.

Business went on all around him, with no explanations. He felt chilled, despite the robe, and thought how desperately he needed his sleep—in order to deal with the dowager in the morning.

“Are there protections around this place?” he asked.

“Assuredly, nadi-ji. This is still a fortress, when it needs to be.”

“With the tourists and all.”

“Tourists. Yes.—There is a group due tomorrow, nadi. Please be prudent. They needn’t see you.”

He felt himself more and more fragile, standing shivering in front of the fire in his night-robe. “Do people ever… slip away from the tour, slip out of the guards’ sight?”

“There’s a severe fine for that,” Jago said.

“Probably one for killing the paidhi, too,” he muttered. His robe had no pockets. You could never convince an atevi tailor about pockets. He shoved his hands up the sleeves. “A month’s pay, at least.”

Jago thought that was funny. He heard her laugh, a rare sound. That was her reassurance.

“I’m supposed to be at breakfast with Tabini’s grandmother,” he said. “Banichi’s mad at me.”

“Why did you accept?”

“I didn’t know I could refuse. I didn’t know what trouble it would make—”

Jago made a soft, derisive sound. “Banichi said it was because you thought he was a dessert.”

He couldn’t laugh for a moment. It was too grim, and on the edge of pain; and then it wasfunny, Banichi’s glum perplexity, his human desperation to find a focus for his orphaned affections. Jago’s sudden, unprecedented willingness to converse.

“I take it this was confused in translation,” Jago said.

“I expressed my extreme respect for him,” he said. Which was cold, and distant, and proper. The whole futile argument loomed up, insurmountable barriers again. “Respect. Favor. It’s all one thing.”

“How?” Jago asked—a completely honest question. The atevi words didn’t mean what he tried to make them mean. They couldn’t, wouldn’t ever. The whole atevi hardwiring was different, the experts said so. The dynamics of atevi relationships were different… in ways no paidhi had ever figured out, either, possibly because paidhiin invariably tried to find words to fit into human terms—and then deceived themselves about the meanings, in self-defense, when the atevi world grew too much for them.

God, why did she decide to talk tonight? Was it policy? An interrogation?

“Nadi,” he said wearily, “if I could say that, you’d understand us ever so much better.”

“Banichi speaks Mosphei’. You should say it to him in Mosphei’”

“Banichi doesn’t feelMosphei’.” It was late. He was extremely foolish. He made a desperate, far-reaching attempt to locate abstracts. “I tried to express that I would do favorable things on his behalf because he seems to me a favorable person.”

It at least threw it into the abstract realm, that perception of luck in charge of the universe, which somewhat passed for a god in Ragi thinking.

“Midei,” Jago declared in seeming surprise. It was a word he’d not heard before, and there weren’t many, in ordinary usage, that he hadn’t. “Dahemidei. You’re midedeni.”

That was three in a row. He was too tired to take notes and the damned computer was down. “What does that mean?”

“Midedeni believe luck and favor reside in people. It was a heresy, of course.”

Of course it was. “So it was a long time ago.”

“Oh, half of Adjaiwaio still believes something like that, in the country, anyway—that you’re supposed to Associate with everybodyyou meet.”

An entire remote Association where people likedother people? He both wanted to go there and feared there were other essential, perhaps Treaty-threatening, differences.

“You really believe in that?” Jago pursued the matter. And it was indeed dangerous, how scattered and longing his thoughts instantly grew down that track, how difficult it was to structure logical arguments against the notion, the very seductive notion that atevi couldunderstand affection. “The lords of technology truly think this is the case?”

Jago clearly thought intelligent people weren’t expected to think so.

Which made him question himself, in the paidhi’s internal habit, whether humans weresomehow blind to the primitive character of such attachments.

Then the dislocation jerked him the other direction, back into belief humans were right. “Something like that,” he said. The experts said atevi couldn’tthink outside hierarchical structure. And Jago said they could? His heart was pounding. His common sense said hold back, don’t believe it, there’s a contradiction here. “So you canfeel attachment to one you don’t have man’chifor.”

“Nadi Bren,—are you making a sexual proposition to me?”

The bottom dropped out of his stomach. “I– No, Jago-ji.”

“I wondered.”

“Forgive my impropriety.”

“Forgive my mistaken notion. What wereyou asking?”

“I—” Recovering objectivity was impossible. Or it had never existed. “I’d only like to read about midedeni, if you could find a book for me.”

“Certainly. But I doubt there’d be one here. Malguri’s library is mostly local history. The midedeni were all eastern.”

“I’d like a book to keep, if I could.”

“I’m sure. I have one, if nothing else, but it’s in Shejidan.”

He’d made a thorough mess. And left a person who was probably reporting directly to Tabini with the impression humans belonged to some dead heresy they probably didn’t even remotely match.

“It probably isn’t applicable,” he said, trying to patch matters. “Exact correspondence is just too unlikely.” Jago had a brain. A very quick one; and he risked something he ordinarily would have said only to Tabini. “It’s the apparent correspondences that can bethe most deceptive. We want to believe them.”

“At very least, we’re polite in Shejidan. We don’t shoot people over philosophical differences. I wouldn’t take such a contract.”

God help him. He thought that was a joke out of Jago. The second for the evening. “I wouldn’t think so.”

“I hope I don’t offend you, nadi.”

“I like you, too.”

In atevi, it was very funny. It won Jago’s rare grin, a duck of the head, a flash of that eerie mirror-luminance of her eyes, quite, quite sober.

“I haven’t understood,” she said. “It eludes me, nadi.”

The best will in the world couldn’t bridge the gap. He looked at her in a sense of isolation he hadn’t felt since his first week on the mainland, his first unintended mistake with atevi.

“But you try, Jago-ji. Banichi tries, too. It makes me less—” There wasno word for lonely. “Less single.”

“We share a man’chi,” Jago said, as if she hadunderstood something he was saying. “To Tabini’s house. Don’t doubt us, paidhi-ji. We won’t desert you.”

Off the meaning again. There was nothing there, nothing to make the leap of logic. He stared at her, asking himself how someone so fundamentally honest, and kind, granted the license she had—could be so absolutely void of what it might take to make that leap of emotional need. It just didn’t click into place. And it was a mistake to pin anything on the Adjaiwaio and any dead philosophy.

Philosophy was the keyword: intellectual, not emotional structure. And a human being, having embraced it, went away empty and in pain.

He said, “Thank you, nadi-ji,” and walked away from the fire to the window, which showed nothing but rain-spots against the dark.

Something banged, or popped. It echoed off the walls, once, twice.

Thatwas no loose shutter. It was off somewhere outside the walls, to the southwest, he thought, beyond the driveway.

The house seemed very still, except the rain and the sound of the fire on the hearth.

“Get away from the window,” Jago said, and he stepped back immediately, his shoulder to solid stone, his heart beating like a hammer as he expected Jago to leave him and rush off to Banichi’s aid. His imagination leapt to four and five assassins breaching the antique defenses of the castle, enemies already inside the walls.

But Jago only stood listening, as it seemed. There was no second report. Her pocket-com beeped—he had not seen it on her person, but of course she had it; she lifted it and thumbed on to Banichi’s voice, speaking in verbal code.

“Tano shot at shadows,” she translated, glancing at him. She was a black shape against the fire. “It’s all right. He’s not licensed.”

Understandable that Tano would make a mistake in judgement, she meant. So Tano, at least, and probably Algini, was out of Tabini’s house guard—licensed for firearms, for defense, but not for their use in public places.

“So was it lightning?” he asked. “Is it lightning they’re shooting at out there?”

“Nervous fingers,” Jago said easily, and shut the com off. “Nothing at all to worry about, nadi-ji.”

“How long until we have power?”

“As soon as the crews can get up here from Maidingi. Morning, I’d say, before we have lights. This happens, nadi. The cannon on the wall draw strikes very frequently. So, unfortunately, does the transformer. It’s not at all uncommon.”

Breakfast might be cancelled, due to the power failure. He might have a reprieve from his folly.

“I suggest you go to bed,” Jago said. “I’ll sit here and read until the rest of us come in. You’ve an appointment in the morning.”

“We were discussing man’chi,” he said, unnerved, be it the storm or the shot or his own failures. He’d gotten far too personal with Jago, right down to her assumption he was trying to approach her for sex, God help him. He was tangling every line of communication he had, he was on an emotional jag, he felt entirely uneasy about the impression he’d left with her, an impression she was doubtless going to convey to Banichi, and both of them to Tabini: the paidhi’s behaving very oddly, they’d say. He propositioned Jago, invited Djinana to the moon, and thinks Banichi’s a dessert.

“Were we?” Jago left the fire and walked over to him, taking his arm. “Let’s walk back to your bedroom, nand’ paidhi, you’ll take a chill—” She outright snatched him past the window, bruising his arm, he so little expected it.

He walked with her, then, telling himself if she were really concerned she’d have made him crawl beneath it—she only wanted him away from a window that would glow with conspicuous light from the fire, and cast their shadows. There were the outer walls, between that window and the lake.

But was it lightning hitting the cannon that she feared?

“Go to bed,” Jago said, delivering him to the door of his bedroom. “Bren-ji. Don’t worry. They’ll be assessing damage. We’ll need to call down to the power station with the information. And of course we take special precautions when we do lose power. It’s only routine. You may hear me go out. You may not. Don’t worry for your safety.”

So one couldcall the airport on the security radio. One would have thought so. But it was the first he’d heard anyone admit it. And having security trekking through his room all night didn’t promise a good night’s sleep.

But he sat down on the bed and Jago walked back to the other room, leaving him in the almost dark. He took off his robe, put himself beneath the skins, and lay listening, watching the faint light from the fireplace in the other room make moving shadows on the walls and glisten on the glass eyes of the beast opposite his bed.

They say it’s perfectly safe, he thought at it. Don’t worry.

It made a sort of sense to talk to it, the two of them in such intimate relationship. It was a creature of this planet.

It had died mad, fighting atevi who’d enjoyed killing it. Nobody needed to feel sorry for anybody. It wasn’t the last of its species. There were probably hundreds of thousands of its kind out there in the underbrush as mad and pitiless as it was.

Adapted for this earth. It didn’t make attachments to its young or its associates. It didn’t need them. Nature fitted it with a hierarchical sense of dominance, survival positive, proof against heartbreak.

It survived until something meaner killed it and stuck its head on a wall, for company to a foolish human, who’d let himself in for this—who’d chased after the knowledge and then the honor of being the best. Which had to be enough to go to bed with on nights like this. Because there damned sure wasn’t anything else, and if he let himself—

But he couldn’t. The paidhi couldn’t start, at twenty-six atevi years of age, to humanize the people he dealt with. It was the worst trap. All his predecessors had battled it. He knew it in theory.

He’d been doing all right while he was an hour’s flight away from Mospheira. While his mail arrived on schedule, twice a week. While…

While he’d believed beyond a doubt he was going to see human faces again, and while things were going outstandingly well, and while Tabini and he were such, such good friends.

Key that word, Friend.

The paidhi had been in a damned lot of trouble, right there. The paidhi had been stone blind, right there.

The paidhi didn’t know why he was here, the paidhi didn’t know how he was going to get back again, the paidhi couldn’t getthe emotional satisfaction out of Banichi and Jago that Tabini had been feeding him, laughing with him, joking with him, down to the last time they’d met.

Blowing melons to bits. Tabini patting him on the back—gently, because human backs fractured so easily—and telling him he had real talent for firearms. How good was Tabini, more to the point? How good at reading the paidhi was the atevi fourth in line of hisside of the bargain?

Tipped off, perhaps, by hispredecessor, that the paidhiin had a soft spot for personal attachments?

That the longer you knew them, the greater fools they became, and the more trusting, and the easier to get things from?

There was a painful lump in his throat, a painful, human knot interfering with his rational assessment of the situation. He’d questioned, occasionally, how long he was good for, whether he couldadjust. Not every paidhi made it the lifelong commitment they’d signed on for, the pool of available advice had dried up—Wilson hadn’t been a damned bit of help, just gotten strange and so short-fused the board had talked about replacing him against Tabini’s father’s expressed refusal to have him replaced. Wilson had had his third heart attack the first month he was back on Mospheira, maintained a grim, passionless demeanor in every meeting the two of them had had, never told him a damned thing of any use.

The board called it burn-out. He’d taken their word for it and tried not to think of Wilson as a son of a bitch. He’d metTabini on his few fill-ins for Wilson’s absences, a few days at a time, the two last years of Valasi’s administration—he’d thought Tabini’s predecessor Valasi a real match for Wilson’s glum mood, but he’d likedTabini—that dangerous word again—but, point of fact, he’d never personally believed in Wilson’s burn-out. A man didn’t get that strange, that unpleasant, without his own character contributing to it. He’d not likedWilson, and when he’d asked Wilson what his impression was of Tabini, Wilson had said, in a surly tone, ‘The same as the rest of them.“

He’d not likedWilson. He hadliked Tabini. He’d thought it a mistake on the board’s part to have ever let Wilson take office, a man with that kind of prejudice, that kind of attitude.

He was scared tonight. He looked down the years he might stay in office and the years he might waste in the foolishness he called friendship with Tabini, and saw himself in Wilson’s place, never having had a wife, never having had a child, never having had a friend past the day Barb would find some man on Mospheira a better investment: life was too short to stay at the beck and call of some guy dropping into her life with no explanations, no conversation about his job—a face that began to go dead as if the nerves of expression were cut. He could resign. He could go home. He could ask Barb to marry him.

But he had no guarantee Barb wantedto marry him. No questions, no commitment, no unloading of problems, a fairy-tale weekend of fancy restaurants and luxury hotels… he didn’t know what Barb really thought, he didn’t know what Barb really wanted, he didn’t knowher in any way but the terms they’d met on, the terms they still had. It wasn’t love. It wasn’t even close friendship. When he tried to think of the people he’d called friends before he went into university… he didn’t know where they were now, if they’d left the town, or if they’d stayed.

He hadn’t been able to turn the situation over to Deana Hanks for a week. Where did he think he was going to find it in him to turn the whole job over to her and walk out—irrevocably, walk out on what he’d prepared his whole life to do?

Like Wilson—a man seventy years old, who’d just seen Valasi assassinated, who’d just come home, because his career ended with Valasi—with nothing to show for forty-three years of work but the dictionary entries he’d made, a handful of scholarly articles, and a record number of vetoes on the Transmontane Highway Project. No wife, no family. Nothing but the university teaching post waiting for him, and he couldn’t communicate with the students.

Wilsoncouldn’t communicate with the human students.

He was going to write a paper when he got out of this, however damning it was, a paper about Wilson, and the atevi interface, and the talk he’d had with Jago, and whyWilson, with that face, with that demeanor, with that attitude, couldn’t communicate with his classes.

Thunder crashed, outside his wall. He jumped, and lay there with his heart doing double beats and his ears still ringing.

The cannon, Jago said. Common occurrence.

He lay there and shook, whether because of the noise, or the craziness of the night. Or because he couldn’t understand any longer why he was here, or why a Bu-javid guard like Tano drew a gun and fired, when they were out there looking at transformers.

Looking at lightning-struck transformers, while the lightning played over their heads and the rain fell on them.

Like hell, he thought, like hell, Jago. Shooting at shadows. What shadows, Jago, is Tano expecting out there in the rain?

Shadows that fly in on scheduled airliners… and the tightest security on the planet, except ours, doesn’t know who it is and where they are?

Like hell again, Jago.