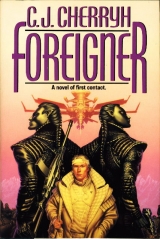

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

I send you a man, ’Sidi-ji…

Wasn’t anything Tabini wouldn’t do, wasn’t anything or anyone Tabini wouldn’t spend. Human-wise, he still likedthe bastard.

He still likedBanichi.

If anybody was alive, Banichi was. And Banichi would have done what that man had done with the last breath in him—but Banichi wouldn’t make dying his first choice: the bastards would pay for Banichi’s life, and Jago’s.

Damn well bet they were free. They were Tabini’s, and Tabini wasn’t here to worry about.

Just him.

They’d have found him if they could.

Tears gathered in the corners of his eyes. One ran down and puddled on the side of his nose. One ran down his cheek to drip off into the weeds. Atevi didn’t cry. One more cosmic indignity nature spared the atevi.

But, over all, decent folk, like the old couple with the grandkids, impulses that didn’t add up to love, but they felt something profound that humans couldn’t feel, either. Something maybe he’d come closer to than any paidhi before him had come—

Don’t wait for the atevi to feel love. The paidhi trained himself to bridge the gap. Give up on words. Try feeling man’chi.

Try feeling why Cenedi’d knocked hell out of him for going after Banichi on that shell-riddled road, try feeling what Cenedi had thought, plain as shouting it: identical man’chi, options pre-chosen. The old question, the burning house, what a man would save…

Tabini’s people, with their own man’chi, together, in Ilisidi’s company.

Jago, violate man’chi?

Not Banichi’s partner.

I won’t betray you, Bren-ji…

Shut up, nadi Bren.

Believe in Jago, even when you didn’t understand her. Feel the warm feeling, call it whatever you wanted; she was on your side, same as Banichi.

Warm feeling. That was all.

There was early daylight bouncing off the pavings. And someone running. Someone shouting. Bren tried to move—his neck was stiff. He couldn’t move his left arm from under him, and his right arm and his legs and his back were their own kind of misery. He’d slept, didn’t remember picking the position, and he couldn’t damned move.

“ Hold it!” came from somewhere outside.

He reached out and cautiously flattened the weeds in front of his nose, with the vast shadow of the tank over his head and the wall cramping his ankle and his knee at an angle.

Couldn’t see anything but a succession of buildings along the runway. Modern buildings. He didn’t know how he’d gotten from ruins to here last night. But it was cheap modern, concrete prefab—two buildings, a windsock. Electric power for the landing lights, he guessed; maybe a waiting area or a machine shop. The wall next to the tank above him was modern, he discovered, sinking down again to ease the strain on his back.

Left arm hurt, dammit. Good and stiff. The legs weren’t much better. Couldn’t quite straighten the one and couldn’t, with the one shoulder stiff, conveniently turn over and get more room.

Gunshots. Several.

Someone of their company, still alive out there. He listened to the silence after, trying to tell himself it wasn’t his affair, and wondering who’d be the last caught, the last killed—he couldn’t but think it could well be Banichi or Jago, while he hid, shivering, and knowing there wasn’t a damned thing he could do.

He felt—he didn’t know what. Guilty for hiding. Angry for atevi having to die for him. For other atevi being willing to kill, for mistaken, stupid reasons, and humans doing things that had nothing to do with atevi—in human minds.

Someone shouted—he couldn’t hear what. He wriggled up on the elbow again, used the back of his hand to flatten the weeds on the view he had of the space between his building and the other frontages.

He saw Cenedi, and Ilisidi, the dowager leaning on Cenedi’s arm, limping badly, the two of them under guard of four rough-looking men in leather jackets, a braid with a blue and red ribbon on the one of them with his back to him—

Blue and red. Blue and red. Brominandi’sprovince.

Damn him, he thought, and saw them shove Cenedi against the wall of the building as they jerked Ilisidi by the arm and made her drop her cane. Cenedi came away from the wall bent on stopping them, and they stopped him with a rifle butt.

A second blow, when Cenedi tried to stand up. Cenedi wasn’t a young man.

“Where’s the paidhi?” they asked. “Where is he?”

“Shejidan, by now,” he heard Ilisidi say.

They didn’t swallow it. They hitIlisidi, and Cenedi swung at the bastards, kicked one in the head before he took a blow from a rifle butt full in the back and another one on the other side, which knocked him to one knee.

They had a gun to Ilisidi’s head, then, and told him stop,

Cenedi did stop, and they hit him again and once more.

“Where’s the paidhi?” they kept asking, and hauled Cenedi up by the collar. “We’ll shoot her,” they said.

But Cenedi didn’t know. Couldn’t betray him, even to save Ilisidi, because Cenedi didn’t know.

“Hear us?” they asked, and slapped Cenedi in the face, slamming his head back into the wall.

They’d do it. They were goingto do it. Bren moved, bashed his head on the tank over him, hard enough to bring tears to his eyes, and, finding a rock among the weeds, he flung it.

That upset the opposition. They shoved Cenedi and Ilisidi back and went casting about for who’d done it, talking on their radio to their associates.

He really had hoped Cenedi could have taken advantage of that break, but they’d had their guns on Ilisidi, and Cenedi wasn’t leaving her or taking any chances with her life—while the search went up and down the frontage and back into the alley.

Boots came near. Bren flattened himself, heart pounding, breaths not giving him air enough.

Boots went away, and a second pair came near.

“Here!” someone shouted.

Oh, damn, he thought.

“You!” the voice bellowed, and he looked up into the barrel of a rifle poking through the weeds, and a man lying flat, the other side of that curtain, staring at him down that rifle barrel, with a certain shock on his face.

Hadn’t seen a human close up, Bren thought—it always jarred his nerves, to see that moment of shock. More so to know there was a finger on the trigger.

“Come out of there,” the man ordered him.

He began to wiggle out of his hole, not noble, nothing gallant about the gesture or the situation. Damned stupid, he said to himself. Probably there was something a lot smarter to have done, but his gut couldn’t take watching a man beaten to death or a brave old woman shot through the head: he wasn’t built that way.

He reached the daylight, crawling on his belly. The rifle barrel pressed against his neck while they gathered around him and searched him all over for weapons.

Besides, he said to himself, the paidhi wasn’t a fighter. The paidhi was a translator, a mediator– wordswere his skill, and if he was with Ilisidi, he might even have a chance to negotiate. Ilisidi had some kind of previous tie to the rebels. There might be a way out of this…

They jerked the rain-cloak off him. The snap resisted, the collar ripped across his neck. He tried to get a knee under him, and two men caught him by the arms and jerked him to his feet.

“He’s no more than a kid,” one said in dismay.

“They come that way,” red-and-blue said. “I saw the last one. Bring him!”

He tried to walk. Wasn’t doing well at it. The left arm shot blinding pain, and he didn’t think they’d listen to argument, he only wanted to get wherever they were going—and hoped they’d bring Cenedi and Ilisidi with him. He needed Ilisidi, needed someone to negotiate for, himself and his loyalties being the bargaining chip…

Claim man’chito Ilisidi: they’d read his actions that way—they could, at least, if he lied convincingly.

They hauled him into the next building, and Cenedi and Ilisidi werebehind him, held at gunpoint, shoved up against the wall, while they said someone’s neck was broken—the man Cenedi had kicked, Bren thought dazedly, and tried to make eye contact with Ilisidi, staring at her in a way atevi thought rude.

She looked straight at him. Gave a tightening of her mouth he didn’t immediately read, but maybe she caught his offer—

Someone grabbed him by the shirt and spun him around and back against the furniture—red-and-blue, it was. A blow exploded across his face, his sight went out, he wasn’t standing under his own power, and he heard Cenedi calmly advising the man humans were fragile and if he hit him like that again he’d kill him.

Nice, he thought. Thanks, Cenedi. You talk to him. Son of a bitch. Tears gathered in his eyes. Dripped. His nose ran, he wasn’t sure with what. The room was a blur when they jerked him upright and somebody held his head up by a fist in his hair.

“Is this yours?” red-and-blue asked, and he made out a tan something on the table where red-and-blue was pointing.

His heart gave a double beat. The computer. The bag beside it on the table.

They had it on recharge, the wire strung across the table.

“Mine,” he said.

“We want the access.”

He tasted blood, felt something running down his chin that swallowing didn’t stop. Lip was cut.

“ Tellus the access code,” red-and-blue said, and gave a jerk on his shirt.

His brain started functioning, then. He knew he wasn’t going to get his hands on the computer. Had to make them axe the system themselves. Had to remember the axe codes. Make them wantthe answer, make them believe it was all-important to them.

“Access code!” red-and-blue yelled into his face.

Oh, God, he didn’t like this part of theplan.

“Fuck off,” he said.

Theydidn’t know him. Set himself right on their level with that answer, he did—he had barely time to think that before red-and-blue hit him across the face.

Blind and deaf for a moment. Not feeling much. Except they still had hold of him, and voices were shouting, and red-and-blue was giving orders about hanging him up. He didn’t entirely follow it, until somebody grabbed his coat by the collar and ripped it and the shirt off him. Somebody else grabbed his hands in front of him and tied them with a stiff leather belt.

He figured it wasn’t good, then. It might be time he should start talking, only they might not believe him. He stood there while they got a piece of electrical cable and flung it over the pipes that ran across the ceiling, using it for a rope. They ran the end through his joined arms and jerked them abruptly over his head.

The shoulder shot fire. He screamed. Couldn’t get his breath.

A belt caught him in the ribs. Once, twice, three times, with all the force of an atevi arm. He couldn’t get his feet under him, couldn’t get a breath, couldn’t organize a thought.

“Access code,” red-and-blue said.

He couldn’t talk. Couldn’t get the wind. There was pain, and his mind went white-out.

“You’ll kill him!” someone screamed. Lungs wouldn’t work. He was going out.

An arm caught him around the ribs. Hauled him up, took his weight off the arms.

“Access,” the voice said. He fought to get a breath.

“Give it to him again,” someone said, and his mind whited out with panic. He was still gasping for air when they let him swing, and somebody was shouting, screaming that he couldn’t breathe.

Arm caught him again. Wood scraped, chair hit the floor. Something else did. Squeezed him hard around the chest and eased up. He got a breath.

Who gave you the gun, nand’ paidhi?

Say it was Tabini.

“Access,” the relentless voice said.

He fought for air against the arm crushing his chest. The shoulder was a dull, bone-deep pain. He didn’t remember what they wanted. “No,” he said, universal answer. No to everything.

They shoved him off and hit him while he swung free, two and three times. He convulsed, tore the shoulder, couldn’t stop it, couldn’t breathe.

“Access,” someone said, and someone held him so air could get to his lungs, while the shoulder grated and sent pain through his ribs and through his gut.

The gun, he thought. Shouldn’t have had it.

“Access,” the man said. And hit him in the face. A hand came under his chin, then, and an atevi face wavered in his swimming vision. “Give me the access code.”

“Access,” he repeated stupidly. Couldn’t think where he was. Couldn’t think if this was the one he was going to answer or the one he wasn’t.

Second blow across the face.

“The code, paidhi!”

“Code…” Please, God, the code. He was going to be sick with the pain. He couldn’t think how to explain to a fool. “At the prompt…”

“The prompt’s up,” the voice said. “Now what?”

“Type…” He remembered the real access. Kept seeing white when he shut his eyes, and if he drifted off into that blizzard they’d go on hitting him. “Code…” The code for meddlers. For thieves. “Input date.”

“Which?”

“Today’s.” Fool. He heard the rattle of the keyboard. Red-and-blue was still with him, someone else holding his head up, by a fist in his hair.

“It says ‘Time,’” someone said.

“Don’t. Don’t give it. Type numeric keys… 1024.”

“What’s that?”

“That’s the code, dammit!”

Red-and-blue looked away. “Do it.”

Keys rattled.

“What have you got?” red-and-blue asked.

‘The prompt’s back again.“

“Is that it?” red-and-blue asked.

“You’re in,” he said, and just breathed, listening to the keys, the operator, skillful typist, at least, querying the computer.

Which was going to lie, now. The overlay was engaged. It would lie about its memory, its file names, its configuration… it’d tell anyone who asked that things existed, tell you their file sizes and then bring up various machine code and gibberish, that said, to a computer expert, that the files did exist, protected under separate passcodes.

The level of their questions said it would get him out of Wigairiin. Red-and-blue was out of his depth.

“What’s this garbage?” red-and-blue demanded, and Bren caught a breath, eyes shut, and asked, in crazed delight:

“Strange symbols?”

“Yes.”

“You’re into addressing. What did you doto it?”

They hit him again.

“I asked the damned file names!”

“Human language.”

Long silence, then. He didn’t like the silence. Red-and-blue was a fool. A fool might do something else foolish, like beat him to death trying to learn computer programming. He hung there, fighting for his breaths, trying to get his feet under him, while red-and-blue thought about his options.

“We’ve got what we need,” red-and-blue said. “Let’s pack them up. Take them down to Negiran.”

Rebel city. Provincial capital. Rebel territory. It was the answer he wanted. He was going somewhere, out of the cold and the mud and the rain, where he could deal with someone of more intelligence, somebody of ambition, somebody with strings the paidhi might figure how to pull, on the paidhi’s own agenda…

“Bring them, too?”

He wasn’t sure who they meant. He turned his head while they were getting him loose from the pipes, and saw Cenedi’s bloodied face. Cenedi didn’t have any expression. Ilisidi didn’t.

Mad, he said to himself. He hoped Cenedi didn’t try any heroics at this point. He hoped they’d just tie Cenedi up and keep him alive until he could do something—had to think of a way to keep Cenedi alive, like ask for Ilisidi.

Make them wantIlisidi’s cooperation. She’d been one of theirs. Betrayed them. But atevi didn’t take that so personally, from aijiin.

He couldn’t walk at first. He yelled when they grabbed the bad arm, and somebody hit him in the head, but a more reasonable voice grabbed him, said his arm was broken, he could just walk if he wanted to.

“I’ll walk,” he said, and tried to, not steadily, held by the good arm. He tried to keep his feet under him. He heard red-and-blue talking to his pocket-com as they went out the door into the cold wind and the sunlight.

He heard the jet engines start up. He looked at the plane sitting on the runway, kicking up dust from its exhaust, and tried to look back to be sure Cenedi and Ilisidi were still with them, but the man holding his arm jerked him back into step and bid fair to break that arm, too.

Long walk, in the wind and the cold. Forever, until the ramp was in front of them, the jet engines at the tail screaming into their ears and kicking up an icy wind against his bare skin. The man holding him let go his arm and he climbed, holding the thin metal handrail with his good hand, a man in front of him, others behind.

He almost fainted on the steps. He entered the sheltered, shadowed interior, and somebody caught his right arm, pulled him aside to clear the doorway. There were seats, empty, men standing back to let them board—Cenedi helped Ilisidi up the steps, and the other men came up after Cenedi.

A jerk on his arm spun him away. He hit a seat and missed sitting in it, trying to recover himself from the moveable seat-arm as a fight broke out in the doorway, flesh meeting bone, and blood spattering all around him. He turned all the way over on the seat arm, saw Banichi standing by the door with a metal pipe in his hand.

The fight was over, that fast. Men were dead or half-dead. Ilisidi and Cenedi were on their feet, Jago and three men of their own company were in the exit aisle, and another was standing up at the cockpit, with a gun.

“Nand’ paidhi,” Banichi gasped, and sketched a bow, “Nand’ dowager. Have a seat. Cenedi, up front.”

Bren caught a breath and slumped, bloody as he was, into the airplane seat, with Banichi and Cenedi in eye-to-eye confrontation and everyone on the plane but him and Jago in Ilisidi’s man’chi.

Ilisidi laid a hand on Cenedi’s arm. “We’ll go with them,” the dowager said.

Cenedi sketched a bow, then, and helped the aiji-dowager to a seat, picking his way and hers over bodies the younger men were dragging out of the way.

“Don’t anybody step on my computer,” Bren said, holding his side. “There’s a bag somewhere… don’t step on it.”

“Find the paidhi’s bag,” Banichi told the men, and one of the men said, in perfect solemnity, “Nadi Banichi, there’s fourteen aboard. We’re supposed to be ten and two crew—”

“Up to ten and crew,” somebody else called out, and a third man, “Dead ones don’t count!”

On Mospheira, they’d be crazy.

“So how many are dead?” the argument went, and Cenedi shouted from up front, “The pilot’s leaving! He’s fromWigairiin, he wants to see to the household.”

“That’s one,” a man said.

“Let that one go,” Bren said hoarsely, with the back of his hand toward the one who’d said his arm was broken, the only grace they’d done him. They were tying up the living, stacking up the dead in the aisle. But Banichi said throw out a dead one instead.

So they dragged red-and-blue to the door and tossed him, and the live one, the one who’d resigned as their pilot, scrambled after him.

Banichi hit the door switch. The door started up. The engines whined louder, the brake still on.

Bren shut his eyes, remembering that height Ilisidi had said rose beside the runway. That snipers could stop a landing.

They could stop a takeoff, then, too.

The door had shut. Engine-sound built and built. Cenedi let off the brakes and gunned it down the runway.

Banichi dropped into the seat next the window, splinted leg stiff. Bren gripped his seat arm, fit to rip the fabric, as rock whipped past the windows on one side, buildings on the other. Then blue-white sky on the left, still rock on the right.

Sky on both sides, then, and the wheels coming up.

“Refuel, probably at Mogaru, then fly on to Shejidan,” Banichi said.

Then, then, he believed it.

XVI

« ^ »

He hadn’t thought of Barb when he’d thought he was dying, and that was the bitter truth. Barb, in his mind and in his feelings, went off and on like a light switch… No, offwas damned easy. Ontook a fantasy he flogged to desperate, dutiful life whenever the atevi world closed in on him or whenever he knew he was going back to Mospheira for a few days vacation.

‘Seeing Barb’ was an excuse to keep his family at arms’ length.

‘Seeing Barb,’ was the lie he told his mother when he just wanted to get up on to the mountain where his family wasn’t, and Barb wasn’t.

That was the truth, though he’d never added it up.

That was his life, his whole humanly-speaking emotional life, such of it as wasn’t connected to his work, to Tabini and to the intellectual exercise of equivalencies, numbers, and tank baffles. He’d known, once, what to do and feel around human beings.

Only lately—he just wanted the mountain and the wind and the snow.

Lately he’d been happy with atevi, and successful with Tabini, and all of it had been a house of cards. The things he’d thought had made him the most successful of the paidhiin had blinded him to all the dangers. The people he’d thought he trusted…

Something rough and wet attacked his face, a strong hand tilted his head back, something roared in his ears, familiar sound. Didn’t know what, until he opened his eyes on blood-stained white and felt the seat arm under his right hand.

The bloody towel went away. Jago’s dark face hovered over him. The engine drone kept going.

“Bren-ji,” Jago said, and mopped at a spot under his nose. Jago made a face. “Cenedi calls you immensely brave. And very stupid.”

“Saved his damn—” Wasn’t a nice word in Ragi. He looked beside him, saw Banichi wasn’t there. “Skin.”

“Cenedi knows, nadi-ji.” Another few blots at his face, which fairly well prevented conversation. Then Jago hung the towel over the seat-back ahead of him, on the other side of the exit aisle, and sat down on his arm rest.

“You were mad at me,” he said.

“No,” Jago said, in Jago-fashion.

“God.”

“What is ‘God?’ ” Jago asked.

Sometimes, with Jago, one didn’t even know where to begin.

“So you’re not mad at me.”

“Bren-ji, you were being a fool. I would have gone with you. You would have been all right.”

“Banichi couldn’t!”

“True,” Jago said.

Anger. Confusion. Frustration, or pain. He wasn’t sure what got the better of him.

Jago reached out and wiped his cheek with her fingers. Business-like. Saner than he was.

“Tears,” he said.

“What’s ‘tears’?”

“God.”

“‘God’ is ‘tears’?”

He had to laugh. And wiped his own eyes, with the heel of the hand that worked. “Among other elusive concepts, Jago-ji.”

“Are you all right?”

“Sometimes I think I’ve failed. I don’t even know. I’m supposed to understand you. And most of the time I don’t know, nadi Jago. Is that failure?”

Jago blinked, that was all for a moment. Then:

“No.”

“I can’t make youunderstand me. How can I make others?”

“But I do understand, nadi Bren.”

“ Whatdo you understand?” He was suddenly, irrationally desperate, and the jet was carrying him where he had no control, with a cargo of dead and wounded.

“That there is great good will in you, nadi Bren.” Jago reached out and wiped his face with her fingers, brushed back his hair. “Banichi and I won over ten others to go with you. All would have gone.—Are you all right, nadi Bren?”

His eyes filled. He couldn’t help it. Jago wiped his face repeatedly.

“I’m fine. Where’s my computer, Jago? Have you got it?”

“Yes,” Jago said. “It’s perfectly safe.”

“I need a communications patch. I’ve got the cord, if they brought my whole kit.”

“For what, Bren-ji?”

“To talk to Mospheira,” he said, all at once fearing Jago and Banichi might not have the authority. “For Tabini, nadi. Please.”

“I’ll speak to Banichi,” she said.

They’d charged the computer for him. The bastards had done that much of a favor to the world at large. Jago had gotten him a blanket, so he wasn’t freezing. They’d passed the border and the two prisoners at the rear of the plane were in the restroom together with the door wedged shut, the electrical fuse pulled, and the guns of two of Ilisidi’s highly motivated guards trained on the door. Everybody declared they could wait until Moghara Airport.

Reboot, mode 3, m-for-mask, then depress, mode-4, simultaneously, SAFE.

Fine, easy, if the left hand worked. He managed it with the right.

The prompt came up, with, in Mosphei’: Input date.

He typed, instead, in Mosphei’: To be or not to be.

System came up.

He let go a long breath and started typing, five-fingered, calling up files, getting access and communications codes for Mospheira’s network, pasting them in as hidden characters that would trigger response-exchanges between his computer and the Mospheira system.

The rebels, if they’d gotten into system level, could have flown a plane right through Mospheira’s defense line.

Could have brought down Mospheira’s whole network. Fouled up everything from the subway system to the earth station dish—unless Mospheira, being sane, had long since realized he was in trouble and changed those codes.

But that didn’t mean they were totally out of commission. They’d just get a different routing until he got clearance.

He hunted and pecked, key at a time, through the initial text.

Sorry I’ve been out of touch…

Banichi had been forward in the plane, standing up, talking to Ilisidi and one of her men, who was sitting at the front. Now he came down the aisle, leaning on seat-backs, favoring the splinted ankle.

“Get off your feet, damn it!” Bren said, and muttered, politely, “Nadi.”

Banichi worked his way to the seat beside him, in the exit aisle, and fell into it with a profound sigh, his face beaded with sweat. But he didn’t look at all unhappy, for a man in excruciating pain.

“I just got hold of Tabini,” Banichi said. “He says he’s glad you’re all right, he had every confidence you’d settle the rebels single-handed.”

He had to laugh. It hurt.

“He’s sending his private plane,” Banichi said. “We’re re-routed to Alujisan. Longer runway. Cenedi’s doing fine, but he says he’s getting wobbly and he’s not sorry to have a relief coming up. We’ll hand the prisoners over to the local guard, board a nice clean plane and have someone feed us lunch. Meanwhile Tabini’s moving forces in by air as far as Bairi-magi, three-hour train ride from Maidingi, two hours from Fagioni and Wigairiin. Watch him offer amnesty next– if, he says, you can come up with a reason to tell the hasdrawad, about this ship, that can calm the situation. He wants you in the court. Tonight.”

“With an answer.” He no longer felt like laughing. “Banichi-ji, atevi have all the rights with these strangers on the ship. We on Mospheira don’t. You know our presence in this solar system was an accident… but our landing wasn’t. We were passengers on that ship. The crew took the ship and left us here. They said they were going to locate a place to build. We weren’t damned happy about their leaving, and they weren’t happy about our threat to land here. Two hundred years may not have improved our relationship with these people.”

“Are they here to take you away?”

“That would make some atevi happy, wouldn’t it?”

“Not Tabini.”

Damned sure not Tabini. Not the pillar of the Western Association. That was why there were dead men on the plane with them: fear of humans was only part of it.

“There are considerable strains on the Association,” Banichi said somberly. “The conservative forces. The jealous. The ambitious. Five administrations have kept the peace, under the aijiin of Shejidan and the dictates of the paidhiin…”

“We don’t dictate.”

“The iron-fisted suggestions of the paidhiin. Backed by a space station and technology we don’t dream of.”

“A space station that sweeps down from orbit and rains fire on provincial capitals at least once a month—we’ve had this conversation before, Banichi. I had it with Ilisidi’s men in the basement. I just had it, abbreviated version, with the gentlemen in the back of the plane, who broke my arm, thank you very much, nadi, but we don’t have any intention of taking over the planet this month.” He was raving, losing his threads. He leaned his head back against the seat. “You’re safe from them, Banichi. At least as far as them coming down here. They don’t like planets to live on. They want us to come up there and maintain their station for them, free of charge, so they can go wherever they like and we fix what breaks and supply their ship.”

“So they will make you go back to the station?” Banichi asked.

“Can’t get at us, I’m thinking. No landing craft. At least they didn’t have one. They’ll have to wait for ourlift capacity.“ He began to see the pieces, then, in a crazed sort of way, while the arm hurt like bloody hell. “Damned right they will. The Pilots’ Guild will negotiate. They’re scared as hell of you.”

“Of us?” Banichi asked.

“Of the potential for enemies.” He turned his head on the head rest. “Time works differently for space travelers. Don’t ask me how. But they think in the long term. The very long term. You’re not likethem, and they can’t keep you at the bottom of a gravity slope forever.” He gave a dry, short laugh. “That was the feud between us from the outset, that some of us said we had to deal with atevi. And the Pilots’ Guild said no, let’s slip away, they’ll never notice us.”

“You’re joking, nadi.”

“Not quite,” he said. “Get some sleep, Banichi-ji. I’m going to do some computer work.”

“On what?”

“Long-distance communications. Extreme long distance.”

Ilisidi was on her feet, hovering over Cenedi’s shoulder, Banichi and Jago were leaning over his. He had the co-pilot’s seat. It was a short patch cord.

“So what do you do?” Ilisidi asked.

“I hit the enter key, nand’ dowager. Just now. It’s talking.”

“In numbers.”

“Essentially.”

“How are these numbers chosen?”

“According to an ancient table, nand’ dowager. They don’t vary from that model—which I assure you we long ago gave to atevi.” He watched the incoming light, waiting, waiting. The yellow light flickered and his heart jumped. “Hello, Mospheira.”

“Can they hear us?” Ilisidi asked.

“Not what we say, at the moment. Only what we input.”

“Dreadful changes to the language.”

“ ‘Put in,’ then, nand’ dowager.” Lights flashed in alternation. ID, came up. The plane was on autopilot, and Cenedi diverted his attention to watch the crawl of letters and numbers on a small screen, all of which ended in:

–the further content of the lines wasn’t available to the screen.

Humans had, at least in design, set up the atevi system. It answered very well when a human transmission wanted through. The systems were talking to each other, thank God, thank God.

The plane hit bumpy air. Pain jotted through the nerve ends in the shoulder. Things went gray and red, and for a moment he had to lean back, lost to here and now.

“Nand’ paidhi?” Jago’s hand was on his cheek.