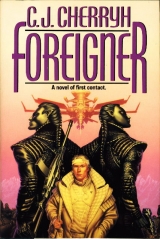

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

VII

« ^ »

In a courtyard echoing with shouts and the squeals of mecheiti, Nokhada extended a leg at his third request, mostly, Bren thought, because the last but her had already done the same.

He slithered down Nokhada’s sun-warmed side, and viewed with mistrust the mecheita’s bending her neck around and nibbling his sleeve, butting capped but still formidable tusks into his side as he tried to straighten the twisted rein. But he wasn’t so foolish as to press on Nokhada’s nose again, and Nokhada lifted her head, sniffing the air, a black mountain between him and the mid-morning sun, complaining at something unseen—or only liking the echoes of her own voice.

The handlers moved in to take the rein. He gave Nokhada a dismissing pat on the shoulder, figuring that was due. Nokhada made a rumbling sound, and ripped the rein from his hand, following the rest of the group the handlers were leading away into the maze of courtyards.

“Use her while you’re here,” Ilisidi said, near him. “At any time, at any hour. The stables have their instructions to accommodate the paidhi-aiji.”

“The dowager is very kind,” he said, wondering if there was skin left on his palm.

“Your seat is still doubtful,” she said, took her cane from an attendant and walked off toward the steps.

He took that for a dismissal.

But she stopped at the first step and looked back, leaning with both hands on her cane. “Tomorrow morning. Breakfast.” The cane stabbed the air between them. “No argument, nand’ paidhi. This is your host’s privilege.”

He bowed and followed Ilisidi up the steps in the general upward flow of her servants and her security, who probably overlapped such functions, like his own.

His lip was swollen, he had lost the outer layer of skin on his right hand, intimate regions of his person were sore and promising to get sorer, and by the dowager’s declaration, he was to come back for a second try tomorrow, a situation into which he seemed to have opened a door that couldn’t be shut again.

He followed all the way up the steps to the balcony of Ilisidi’s apartment, that being the only way up into the castle he knew, while the dowager, on her way into her inner apartments, paid not the least further attention to his being there—which was not the rudeness it would have been among humans: it only meant the aiji-dowager was disinterested to pursue business further with an inferior. At their disparity of rank she owed him nothing; and in that silence, he was free to go, unless some servant should deliver him some instruction to the contrary.

None did. He trailed through the dowager’s doorway, and on through the public reception areas of her apartment, tagged all the way by her lesser servants, who opened the outermost doors for him and bowed and wished him good fortune in his day as he left.

Good fortune, he wished them, in his turn, with appropriate nods and bows on their part, after which he trekked off down the halls, bruised and damaged, but with a knowledge now of the land, the provinces, the view and the command of the castle, and even what was the history and origin of the cannon he could see through the open front doors.

Where—God help him—several vehicles were parked.

Perhaps some official had come up from the township. Perhaps the promised repair crew had arrived and they were putting the electricity back in service. In any event, the paidhi wasn’t a presence most provincial atevi would take without flinching. He decided to hurry, and traversed the front room at a fast, sore-legged walk.

Straight into an inbound group of the castle staff and a flock of tourists.

A child screamed, and ducked behind its parents. Parents stood stock still, a black wall with wide yellow eyes. He made an apologetic and sweeping bow, and—it was the paidhi’s minimal job—knew he had to patch the damage, wild as he must look, with a cut lip, and dust on his coat.

“Welcome to Malguri,” he said. “I’d no idea there were visitors. Please reassure the young lady.” A pause for breath. A second bow. “The paidhi, Bren Cameron, at your kind disposal. May I do you any grace?”

“May we have a ribbon?” an older boy was forward to ask.

“I don’t know that I have ribbons,” he said. He did, sometimes, have them in his office for formalities. He didn’t know whether Jago had brought such things. But one of the staff said they could procure them, and wax, if he had his seal-ring.

He was trapped. Banichi wasgoing to kill him.

“Excuse me,” he said. “I’ve just come in from the stable court. I need to wash my hands. I’ll be right back down. Excuse me, give you grace, thank you…” He bowed two and three times more and made the stairs, was halfway up them when he looked up.

Tano was standing at the top of the stairs with no pleased expression on his face, a gun plainly on his hip. Tano beckoned him to come upstairs, and he ran the rest of the steps, the whole transaction between them at such an angle, he hoped, that the tourists couldn’t see the reason for his sudden burst of energy.

“Nand’ paidhi,” Tano said severely. “You were to use the back hall.”

“No one told me, nadi!” He was furious. And held his temper. The culprit was Banichi, who was in charge—and the second party responsible was clearly himself. “I need to clean up. I’ve promised these people—”

“Ribbons, nand’ paidhi. I’ll see to it. Hurry.”

He flew up the stairs past Tano, aches and all, down the hall to his apartment, with no time to bathe. He only washed, flung on fresh shirt and trousers, a clean coat, and passed cologne-damp hands over his windblown hair, which was coming out of its braid.

Then he stalked out and down the hall, and made a more civilized descent of the stairs to what had been set up as a receiving line, a place ready at the table in the hall in front of the fireplace, with wax-jack, with ribbons, with small cards, and an anxious line of atevi—for each of them, a card to sign, ribbon and seal with wax, and, with the first such signature and seal, a pleased and nervous tourist who’d received a bonus for his trip, while a line of thirty more waited, stealing glances past one another at the only living human face they’d likely seen, unless they’d been as far as Shejidan.

The paidhi was used to adult stares. The children were far harder to deal with. They’d grown up on machimi about the War. Some of them were sullen. Others wanted to touch the paidhi’s hand to see if his skin was real. One asked him if his mother was that color, too. Several were afraid of his eyes, or asked if he had a gun.

“No, nadi,” he lied to them, with mostly a clear conscience, “no such thing. We’re at peace now. I live in the aiji’s house.”

A parent asked, “Are you on vacation, nand’ paidhi?”

“I’m enjoying the lake,” he said, and wondered if his attempted assassination was on the television news yet, in whatever province the man came from. “I’m learning to ride.” He poured wax and sealed the ribbon to the card. “It’s a beautiful view.”

Thunder rumbled. The tourists looked anxiously to the door.

“I’ll hurry,” he said, and began to move the line faster, recalling the black cloud that they had seen from the ridge, down over the end of the lake—the daily deluge, he said to himself, and wondered whether it was the season and whether perhaps there was a reason why Tabini came here in the autumn, and not mid-summer. Perhaps Tabini knew better, and sent the paidhi here to be drowned.

The electricity was still off. “It looks so authentic,” one visitor said to another, regarding the candlelight.

Tour the bathrooms, he thought glumly, and longed for the hot bath that would take half an hour at least to heat. He felt the least small discomfort sitting on the hard chair, that had everything to do with the riding-pad and Nokhada’s gait, and the stretching of muscles in places he’d been unaware separate muscles existed.

A humid, cold gust of wind swept in the open front doors, fluttering the candles and making a sputter of wax from the wax-jack that sprinkled the polished wood of the table. He thought of calling out to the staff to shut the door before the rain hit, but they were all out of convenient range, and he was almost finished. The tourists would be outbound in only another moment or two, and the door was providing more light to the room than the candles did.

Thunder boomed, echoing off the walls, and he was down to the last two tourists, an elderly couple who wanted “Four cards, if the paidhi would, for the grandchildren.”

He signed and sealed, while the tourists with their ribboned cards were congregating by the open doors. The vans were pulling around, and the air smelled like rain, sharp contrast to the smell of sealing-wax.

He made an extra card, his last ribbon, for the old man, who told him his grandchildren were Nadimi and Fari and Tabona and little Tigani, who had just cut her first teeth, and his son Fedi was a farmer in Didaini province, and would the paidhi mind a picture?

He stood, feeling the stretch of stiffening muscles, he smiled at the camera, and at the general click of shutters as others took it for permission. He felt much better about the meeting, encouraged that the tourists proved approachable, even the children behaving far more easily toward him. It was the closest he supposed he’d ever come to meeting ordinary folk, except the very few he met in audience in Shejidan, and in the success of the gesture and in the habits of his job he felt constrained to a reciprocal courtesy, seeing them to the doors and onto their buses—always good policy, the extra gesture of good will, despite the chill; and he likedthe old couple, who were following at his elbow and asking him about his family. “No, I don’t have a wife,” he said, “no, I’ve thought about it—”

Barb would die of boredom and frustration, in the cloister the paidhi lived in. Barb would stifle in the surrounding security, and as for being circumspect—her life wouldn’t tolerate the board’s questions, she wouldn’t pass

… and Barb… he didn’t loveher, but she was what he needed.

A boy crowded near him, right up against his arm, and said, not too discreetly, “I’m that tall, look.” Which was the truth. But his parents hastily snatched him away, declaring that that was a very insheibithing to say, very indiscreet, rude and dangerous, and begging the paidhi’s pardon could they possibly take a picture with him if a member of the paidhi’s staff could possibly snap the shutter?

He smiled, atevi-style, waited while they arranged the shot, and looked civilized and as comfortable as possible, standing with the couple as the camera clicked.

More cameras went off, the moment he stepped away, a veritable barrage of shutters.

And a random three pops outside the open doors. He turned in a heart-frozen shock, recognizing the sound of gunfire, as someone grabbed him by the arm and slammed him against the open door—as the tourists all rushed out under the portico in the rain.

Another shot rang out. The tourists cheered.

It was Tano half-smothering him, when he hadn’t even known Tano was close. “Stay here,” Tano said, and went outside, his hand on his gun.

He couldn’t stand there not knowing what was happening, or what the danger was. He risked a glance after Tano’s departing back, keeping the rest of him behind the substantial door. He saw, in the gaps of a screen of tourists, a man lying on the pavings out in the rain, and at the same remove, atevi figures coming from the lawn to the circular drive, near the cannon, mere shadows through the veils of rain. A bus driver, ignoring the whole affair, was shouting for his tourists to get aboard, that they had a long drive today, and a schedule for lunch on the lake, if the weather passed.

The tourists boarded, while the atevi shadows stood around the man lying on the cobbles. He supposed the shooting was over. He came out and stood in front of the door as the damp gusts hit him. Tano came back in haste.

“Get inside, nand’ paidhi,” Tano said. The first van was moving out, tourists pressing their faces to the windows, a few waving. He waved back, helpless habit, frozen by the grotesqueness of the sight. The van made the circular drive past the cannon and the second bus passed him.

“It’s handled, nand’ paidhi, get inside. They think it was machimi for the tourists, it’s all right.”

“All right?” He held his indignation in check and steadied his voice. “Who’s been killed? Who is it?”

“I don’t know, nand’ paidhi, I’ll try to find out, but I can’t leave you down here. Please go upstairs.”

“Where’s Banichi?”

“Out there,” Tano said. “Everything’s all right, nadi, come, I’ll take you to your rooms.” Tano’s pocket-com sputtered, and Tano turned it on, one-handed. “I have him,” Tano said. It was Banichi’s voice, Bren thought, thank God it was Banichi, but where was Jago? He heard Banichi saying something in verbal code, about a problem solved, and then another voice—telling gender with atevi voices wasn’t always easy—saying something about a second team and that being all right.

“The dowager,” Bren said in a low voice, suddenly asking himself—one had to ask, with the evidence of death on the grounds—was Ilisidi somehow involved, was she all right, was she somehow the author of what was happening out there, with Banichi?

“Perfectly safe,” Tano said, and gave him another gentle shove. “Please, nadi, Banichi’s fine, everyone is fine—”

“Who’s dead? An outsider? Someone on staff?”

“I’m not quite sure,” Tano said, “but please, nadi, don’t make our jobs more difficult.”

He let himself be maneuvered away from the doors, then, away from the blowing mist that made his clothing damp and cold, and across the dim hall and up the stairs. All the while he was thinking about the shadows in the rain, about Banichi out there, and someone lying dead on the cobbled drive, right by the flower beds and the memorial cannon—

Thinking uneasily, too, about the alarm last night, and about riding up on the ridge not an hour ago, with Ilisidi and Cenedi, where any rifle might have picked them off. The vivid memory came back, of that night in Shejidan, and the shock of the gun in his hands, and Jago saying, like a bad dream, that there was blood on the terrace. Like outside, on the lawn, in the rain.

His knees started shaking as he climbed the stairs to the upper hall. His gut was upset before he reached the doors to his apartment, as if it werethat night, as if everything was slipping again out of his control.

Tano strode two steps ahead of him at the last and opened the door to his receiving room, to what should feel like refuge, where warm air met him like a wall and light flooded in from a window blind with rain. Lightning flashed, making the window white for an instant. The tourists were having a rain-drenched ride down the mountain. Their lunch on the lake seemed uncertain.

Someone had invaded the grounds last night and that someone was dead on the drive, all his plans cancelled. It hardly seemed reasonable that no one knew what they were.

Tano rang for the other servants, and assured him in a low voice that hot tea was forthcoming. “A bath,” Bren said, “if they can.” He didn’t want to deal with Djinana and Maigi right now, he wanted Tano, he wanted people he knew were Tabini’s—but he was scared to protest that to Tano, as if a question to their plans could turn into a challenge to their conspiracy of silence, a sign that the prisoner had gained the spirit to rebel, a warning that his guards should be more careful—

Another stupid thought. Banichi and Jago were the ones he wanted near him, and Tano had said it, his personal needs could only hinder whatever investigation Banichi was pursuing out there. He didn’t needto know on the same level that Banichi needed to be following that trail in the rain, needed to be asking questions among the staff, like how that person had gotten in or whether he had come with the bus or whether Banichi had somehow made a terrible mistake and it was just some poor, mistaken tourist out on the lawn for a special camera angle.

The people on the bus would miss one of their own number, wouldn’t they? Wouldn’t one or the other busloads be asking why a seat was vacant, or who that had been, or had it all been machimi, just an actor, all along, an entertainment for their edification? Wasn’t it historic, and educational, here at Malguri, where fatal accidents happened on the walks?

Djinana and Maigi were quick to answer his summons, and hastened him out of Tano’s care and into the drawing room in front of the fire—peeling him out of his damp coat as they went and asking him how breakfast had gone with the dowager… as if no tourists had come in, as if nothing was going on out there, with any possible relevancy to anyone’s life—

Where was Algini? he suddenly wondered. He hadn’t seen Tano’s partner since yesterday, and someone was dead out there. He hadn’t seenAlgini last night, just shadows passing through his room. He hadn’t seen Algini maybe since the day before… what with the incident with the tea, he’d lost his sense of time since he’d left Shejidan,

Tano hadn’t looked worried. But atevi didn’t always express things with their faces. Didn’t always express whal they felt, if they felt, and you didn’t know…

“Start the heater,” Maigi said to Djinana, and flung a lap-robe about him. “Nadi, please sit down and stay warm. I’ll help you with the boots.”

He eased down into the chair in front of the fire, while Maigi tugged the boots off. His hands were like ice. His feet were chilled, for no good reason at all. “Someone was shot outside,” he said in a sudden reckless mood, challenging Maigi’s silence on the matter. “Do you know that?”

“I’m sure everything’s taken care of.” Maigi knelt on the carpet, warming his right foot with vigorous rubbing. “They’re very good.”

Banichi and Jago, Maigi seemed to mean. Very good. A man was dead. Maybe it was over, and he could go back tomorrow, where his computer would work and his mail would come.

With the electricity still out, and tourists coming and going, and the dowager exposing all of them to danger on a morning ride?

Why hadn’tBanichi interposed some warning, if Banichi had any warning there was someone loose on the grounds, and why hadn’tBanichi’s warning gotten to him about the tourists?

Or hadn’t Jago said something to him, yesterday—something about a tour,—but he hadn’t remembered, dammit, he’d been thinking about the other mess he’d gotten himself into, and it hadn’t stuck in his mind.

So it wasn’t their fault. Somebody had been chasing him, and he had walked in among the tourists, where someone else could have gotten shot—if his guards hadn’t, in the considerations of finesse, somehow protected him by being there.

He felt cold. Maigi tucked him into the chair with the robe and brought in hot tea. He sat with his robe-wrapped feet propped in front of the fire, while the thunder boomed outside the window and the rain whipped at the glass, a level above the walls. The window faced the straight open sweep off the lake. It sounded like gravel pelting the glass. Or hail. Which made him wonder how the windows withstood it: whether they were somehow reinforced—and whether they were, considering the wall out there, and the chance of someone climbing it, also bulletproof.

Jago had wanted him clear of it, last night. Algini had disappeared, since before last night. The power had failed.

He sat there and kept replaying the morning in his head, the breakfast, the ride, Ilisidi and Cenedi, and the tourists and Tano, most of all the happy faces and the hands waving at him from the windows of the buses, as if everything was television, everything was machimi. He’d made a slight inroad into the country, met people he’d convinced not to be afraid of him, like the kids, like the old couple, and someone got shot right in front of them.

He’d fired a gun, he’d learned he wouldshoot to kill, for fear, for—he was discovering—for a terrible, terrible anger he had, an anger that was still shaking him—an anger he hadn’t known he had, didn’t know where it had started, or what it wanted to do, or whether it was directed at himself, or atevi, or any specific situation.

It hadn’t been a false alarm last night—or it was, Barb would say, one hell of a coincidence. Maybe Banichi had thought last night he was safe, and whoever it was had simply gotten that far within Banichi’s guard. Maybe they’d been tracking the assassin all along, and let him go off with Ilisidi this morning in the hope he’d draw the assassin out of cover.

Too much television, Banichi had said, that night with the smell of gunpowder in his room, and rain on the terrace. Too many machimi plays.

Too much fear in children’s faces. Too many pointing fingers.

He wanted his mail, dammit, he wanted just the catalogs, the pictures to look at. But they weren’t going to bring it.

Hanks might have missed him by now, tried to call his office and not gotten through.

On vacation with Tabini, they’d say. Hanks might know better. They monitored atevi transmissions. But they wouldn’t challenge the Bu-javid on the point. They’d go on monitoring, once they were alert to trouble, trying to find him—and blame him for not doing his job. Hanks would start packing to assume his post. Hanks always had resented his winning it over her.

And Tabini would detest Hanks. He could tell the Commission that, if they didn’t think it self-serving, and part of the feud between him and Hanks.

But if he was so damned good at predicting Tabini—or reading situations—he couldn’t prove it from where he sat now. He hadn’t made the vital call, he hadn’t put Mospheira alert to the situation—

God, that was stupid. He had the willies over some misguided lunatic and now he saw the Treaty collapsing, as if atevi had been waiting all these centuries only to resume the War, hiding a missile program they’d built on their own, launching warheads at Mospheira.

It was as stupid as atevi with their planet-skimming satellites shooting death rays. Relations between Mospheira and Shejidan hadbad periods. Tabini’s administration was the least secretive, the easiest to deal with of all the administrations they’d ever dealt with.

“Death rays,” Tabini would say, and laugh, invite him to supper and a private drink of the vice humans and atevi held in common. Laugh, Tabini would say. Bren, there are fools on Mospheira and fools in the Bu-javid. Don’t take them seriously.

Steady hand, Bren-ji, like pointing the finger, there’s no difference.

Good shot, goodshot, Bren…

Rain… pelted the window. Washed evidence away. Buses rolled away down the road, the tourists laughed, amazed and amused by their encounter.

They hadn’t hated him. They’d wanted photographs to prove his existence to their neighbors…

“Nadi,” Djinana said, from the doorway. “Your bathwater’s ready.”

He gathered the fortitude to move, tucked his robe about him and went with Djinana through the bedroom, through the hall and the clammy accommodation, into the overheated air of the bath, where he could shed the blanket and the rest of his clothes, to sink neck-deep into warm, steamy water.

Clouds rose around him. The water invaded the aches he wouldn’t admit to. He could lie and soak and stare stupidly at the ancient stonework around him—ask himself important questions such as why the tub didn’t fall through the floor, when the whole rest of the second floor was wood.

Or things like… why hadn’t the two staffs advised each other about the alarm last night, and why had Cenedi let them go out there?

They’d talked about cannon, and ancient wars.

Everything blurred. The stones, the precariousness, the age, the heat, the threat to his life. The storm noise didn’t get here. There was just the occasional shock of thunder through the stones, like ancient cannon shots.

And everyone saying, It’s all right, nand’ paidhi, it’s nothing for you to worry about, nand’ paidhi.

He heard footsteps somewhere outside. He heard voices that quickly died away.

Banichi coming back, maybe. Or Jago or Tano. Even Algini, if he was alive and well. Nothing in the house seemed to be an emergency. In the failure of higher technology, the methane burner worked.

The paidhi was used to having his welfare completely in others’ hands. There was nothing he could do. There was nowhere he could go.

He lay still in the water, wiggling his toes, which were cramped and sore from the boots, and ankles which were stiffening from the stress of staying on the mecheita’s back. He must have clenched his legs all the way. He sat there soaking away the aches until the water began to cool and finally climbed out and toweled himself dry—Djinana would gladly help him, but he had never had that habit with his own servants, let alone with strangers. Let alone here.

So he put on the dressing-robe Djinana had laid out, and went back to the study to sit in front of his own safe fire, read his book and wait for information, or release, or hell to freeze over, whichever came first.

Maybe they’d caught the assassin alive. Maybe they were asking questions and getting answers. Maybe Banichi would even tell him if that was the case—

Or maybe not.

“When will we have power?” he asked Djinana, when Djinana came to ask if the paidhi wanted anything else. “Do they give any estimate?”

“Jago said something about ordering a new transformer,” Djinana said, “by train from Raigan. Something blew out in the power station between here and Maidingi. I don’t know what. The paidhi probably understands the systems far better than I do.”

He did. He hadn’t realized there was a secondary station. Nobody had said there was—only the news that a quarter of Maidingi was waiting on the same repair. It was logical a power station should attract lightning, but it wasn’t reasonable that no one within a hundred miles could bring power back to a major section of a township without parts freighted in.

“This isn’t a poor province. This has to happen from time to time. Does it happen every summer?”

“Oh, sometimes,” Djinana said. “Twice last.”

“Does it happen assassins get in? Does thathappen?”

“Please be assured not, nand’ paidhi. And it’s all right now.”

“Is he dead? Do they know who he was?”

“I don’t know, nand’ paidhi. They haven’t told us. I’m sure they’re trying to find out. Don’t worry about such things.”

“I think it’s natural I worry about such things,” he muttered, looking at his book. And it wasn’t fair to take his frustration out on Djinana and Maigi, who only worked here, and who would take Malguri’s reputation very personally. “I would like tea, Djinana, thank you.”

“With sandwiches?”

“I think not, Djinana, thank you, no. I’ll sit here and read.”

There were ghost ships on the lake. One was a passenger ship that still made port on midwinter nights, once at Maidingi port itself, right under the lights, and tried to take aboard the unwary and the deservedly damned, but only a judge-magistrate had gone aboard, a hundred years ago, and it had never made port again.

There was a fishing boat which sometimes appeared in storms—once, not twenty years ago, it had appeared to the crew of a stranded net-fisher that was taking on water and sinking. All but two had gone aboard, the captain and his son electing to stay with their crippled trawler. The fishing boat, which everyone had remarked to be old and dilapidated, had sailed away with the crew, never to be seen again.

Everything in the legends seemed to depend on misplaced trust, though atevi didn’t quite have the word for it: ghosts lost all power if the victims didn’t believe what they saw, or if they knew things were too good to be true, and refused to deceive themselves.

Banichi still hadn’t come back. Maigi and Djinana came asking what he wanted for dinner, and recommended a game course, a sort of elusive, cold-blooded creature he didn’t find appetizing, though he knew his servants thought it a delicacy. He asked for shellfish, instead, and Maigi thought that easy, though, Djinana said, the molluscs might not be the best this time of year: they would send down to town and they might have them, but it might be two or three hours or so before they could present them.

“Waiting won’t matter,” he said, and added, “they might lay in some more for lunch tomorrow.”

“There’s no ice,” Djinana said apologetically.

“Perhaps in town.”

“One could find out, nadi. But a great deal of the town is without power, and most houses will buy it up for their own stock. We’ll inquire…“

“No, no, nadi, please.” He survived on shellfish, in seasons of desperation. “Others doubtless need the ice. And if they can’t preserve it—please, take no chances. If the household could possibly arrange to find me fruited toast and tea, that would do quite well. I’ve no real appetite this evening.”

“Nadi, you must have more than toast and tea. You missed lunch.”

“Djinana-nadi, I must confess, I find the season’s dish very strong… a difference in perceptions. We’re quite sensitive to alkaloids. There may be some somewhere in the preparations, and it’s absolutely essential I avoid them. If there were any kabiuchoice of fruit or vegetables… The dowager-aiji had very fine breakfast rolls, which I very much favor.”

“I’ll most certainly tell the cook. And—” Djinana had a most conspiratorial look. “I do think there’s last month’s smoked joint left. It’s certainly not un-kabiu, if it’s left over. And we always put by several.”

Preserved meat. Out of season, God save them.

“We never know how many guests,” Djinana said, quite straight-faced. “We’d hate to run short.”

“Djinana-nadi, you’ve saved my life.”

Djinana was highly amused, very pleased with their solution, and bowed twice before leaving.

Whereupon, for the rest of the afternoon, he went back to his ghost ships, and his headless captains of trawlers that plied Malguri shores during storms. A bell was said to ring in the advent of disasters.

Instead there was an opening of the door, a squishing of wet boots across the drawing room, and a very wet and very tired-looking Banichi, who walked into the study, and said, “I’ll join you for dinner, nadi.”