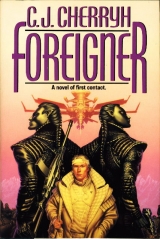

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

VIII

« ^ »

Anoisy night,” Ilisidi said, pouring her own tea—the smell of it drifted with the steam, across the table, and Bren’s stomach went queasy.

“I’m extremely sorry,” he said, “and embarrassed, aiji-mai.”

Ilisidi grinned, positively grinned, and added sugar.

It was little barbs all during breakfast. Ilisidi was in an excellent humor. She wolfed down four fish, a bowl of cereal and two cakes with sweet oil, while he stayed to the cereal and the breakfast rolls, thinking that, considering the pain he was in sitting on a hard chair this morning, he would almost rather drink Ilisidi’s tea than get onto Nokhada’s back again.

But it was downstairs, Ilisidi reveling in the stiff breeze blowing in off the lake, a breeze that tore at coat-skirts and knifed right through sweaters when one passed out of the sunlight and into the stable court.

Nokhada at least was willing to get down for him this morning, and this time, at least, he was ready for the snap of Nokhada’s rising before he was quite astride.

It hurt. God, it hurt. Not exactly the kind of pain a man could admit to, or beg off from. He only hoped for early numbness, and told himself his human ancestors had been riders, and somehow continued the species.

He brought a quick stop to Nokhada’s milling about, determined to have the final word on their course this morning—which lasted until Ilisidi moved Babs out and Nokhada jostled Cenedi’s mecheita for position at Babs’ tail in a sudden dash out onto the road.

Straight out. Ilisidi and Babs vanished over the cliff, a stride or two before Nokhada won out over Cenedi’s mount and took the same downward plunge.

Onto what thank God was trail and not empty air.

He didn’t yell, and didn’t object, though his legs did, and for a moment the pain was acute, in a dozen jolting strides down a dusty slot of a trail that began above the point where Nokhada had thrown the fit yesterday about the rein.

If they had gone off then, they would nothave fallen, damn the creature. Gone an embarrassing long distance down to a second terrace above the lake, indeed they would, but there was such a terrace, whether or not, yesterday, at the start of the ride, he might have had the ability to stay on Nokhada’s back.

And he found it equally interesting that, with the plunge over the cliff available for the novice fool, Ilisidi had taken them straight up the mountain yesterday, however rough the course. A second chance missed, then. So maybe the tea was, after all, an accident.

Although, given there had been an intruder on the grounds yesterday, maybe getting them over the ridge or above line-of-sight from the fortress had been a priority.

And given Banichi’s comment about having had them under direct surveillance…

“Why didn’t you tell me yesterday that there was a possibility of someone out there?” he asked Cenedi, with the rest of the dowager’s guard trailing behind. “You knew we were in danger yesterday. Banichi informed you.”

“The outriders,” Cenedi said, “were well alert. And Banichi was never far.”

“Nadi, a risk to the dowager? In all respect, is that reasonable?”

“With Tabini’s man?” Cenedi’s face had things in common with Banichi’s. Just as expressive. “No. It wasn’t a risk.”

Not a risk? A compliment to Banichi, perhaps, but damned well a risk, under any human interpretation of the word, unless, the thought that had jogged his attention last night, there were more security systems about than either Banichi or Cenedi was going to own to. He rode by Cenedi in thinking silence, with the waves lapping the rocks below. The sky was blue. The waters danced. A dragonette soared past Nokhada’s face and made her jump, a single heart-stopping moment, close to the edge.

“Damn!” he said, and he and Nokhada had a silent war for a moment, at which Cenedi maintained complete lack of expression, and complete control of his mecheita.

Ilisidi rode ahead of them, oblivious, seemingly, to all of it. When he tilted his head back and looked up he couldn’t see the fortress walls at all, just the bowed face of the rocks and, behind them, the very edge of the modern wall that divided off the paved court from the trail. Ahead, the trail wound higher on the mountain, until they came to a promontory with a dizzying view, where Ilisidi stopped and let Babs stand, and where, when he arrived, he sat doing the same with Nokhada, telling himself that if Babs didn’t fling himself over the cliff, Nokhada wouldn’t, and he needn’t worry.

“Glorious day,” Ilisidi said.

“An unforgettable view,” he said, and thought that he never wouldforget it, the chanciness of their height, the power of the creature under him, the startling panorama of the lake spread out around them as far as the eye could see. skiing with Toby, he had had such sights, but never one fraught with atevi significances, never one once foreign and now freighted with names, and identity, and history. The Bu-javid—with its pressures, its schedules, its crowds of political favor-seekers—had no such views, no such absolute, breath-taking moments as Malguri offered… between hours, as yesterday, of cloistered, stifling silence, headaches from oil-burning lamps, cold, dark spots in the corners of cavernous halls and knees blistered from proximity to a waning fire.

Not to mention the plumbing.

But it had its charm. It hadits moments, it had the incredible texture of life that didn’t measure by straight lines and standardized measures, that didn’t go by streets and straight edges, with people living stacked up on top of each other, and lights blotting out the stars at night. Here, one could hear the wind and the waves, one could find endless variety in weathered stones and pebbles and there was no schedule but the inescapable fact that riding out and riding back were the same distance…

Ilisidi talked about the trading ships and the fishermen, while the high, thin trail of a jet passed above Malguri on its way east, across the continental divide, across the barrier that had held two atevi civilizations from meeting for thousands of years—a matter of four, five hours, now, that easy. But Ilisidi talked about crossings of Maidingi that took days, and involved separate aijiin’s territory.

“In those days,” Ilisidi said, “one proceeded very carefully into the territory of foreign aijiin.”

Not without a point. Again.

“But we’ve learned so much more, nand’ dowager.”

“More than what?”

“That walling others out equally walls us in, nand’ dowager.”

“Hah,” Ilisidi declared, and with a move he never saw, spun Babs about and lit out along the hill, scattering stones.

Nokhada followed. All of them had to. And it hurt, God, it hurt when they struck the downhill to the lake. Ahead of them, Ilisidi, with her white-shot braid flying—no ribbon of rank, no adornment, just a red and black coat, and Babsidi’s sleek black rump, tail switching for nothing more than excess energy—nothing more in Ilisidi’s mind, perhaps, than the free space in front of her.

Catching up was Nokhada’s idea; but with the rest of the guard behind, and Cenedi beside, there was nothing to do but follow.

At another time they stopped, on the narrow half-moon of a sandy beach, where the lake curved in, and a man thinking of assassins could only say to himself that there were places on the shore where a boat could land and reach Malguri.

But standing while the mecheiti caught their breaths, Ilisidi talked about the lake, its depth, its denizens—its ghosts. “When I was a child,” she said, “a wreck washed up on the south shore, just the bow of it, but they thought it might be from a treasure ship that sank four hundred years ago. And divers went out for it, all up and down this shore. They say they never found it. But a number of antiquities turned up in Malguri, and the servants were cleaning them in barrels in the stable court, about that time. My father sent the best pieces to the museum in Shejidan. And it probably cost him an estate. But most people in Maidingi province would have melted them for the gold.”

“It’s good he saved them.”

“Why?”

“For the past,” he said, wondering if he had misunder stood something else in atevi mindset. “To save it. Isn’t that important?”

“Is it?” Ilisidi answered him with a question and left him none the wiser. She was off again up the hill, and he forgot all his philosophy, in favor of protecting what he feared might have progressed to blisters. Damn the woman, he thought, and thought that if he pulled up and lagged behind as long as he could hold Nokhada’s instincts in check, the dowager might take that for a surrender and slow down, but damnedif he would, damnedif he would cry help or halt. Ilisidi would dismiss him from her company then, probably lose all interest in him, and he could lie about in a warm bath, reading ghost stories until his would-be assassins flung themselves against the barriers Banichi had doubtless set up, and killed themselves, and he could go home to air-conditioning, the morning news, and tea he could trust. From moment to moment it seemed like the only escape.

But he kept Ilisidi’s pace. Atevi called it na’itada. Barb called it being a damned fool. He had never spent so long an hour as it took to get home again, an hour in which he told himself repeatedly he had rather fall off the mountain and be done.

Finally the gates of the stable court were in front of them, then behind them, with the mecheiti anxious for stables and grain. He managed to get Nokhada to drop a shoulder, and climbed down off Nokhada’s towering height onto legs he wasn’t sure would bear his weight.

“A hot bath,” Ilisidi called out to him. “I’ll send you some herbs, nand’ paidhi. I’ll see you in the morning!”

He managed to bow, and, among Ilisidi’s entourage, to walk up the stairs without conspicuously limping.

“The soreness goes,” Cenedi said to him quietly, “in four or five days.”

A hot bath was all he was thinking of, all the long way up to the front hall. A hot bath, for about an hour. A soft and motionless chair. Soaking and reading seemed an excellent way to spend the remainder of the day, sitting in the sun, minding his own business, evading aijiin and their athletic endeavors. He limped down the long hall and started the stairs up to his floor, at his own pace.

Quick footsteps crossed the stone floor below the stairs. He looked back in some concern for his safety in the halls and saw Jago coming toward the stairs, all energy and anxiousness. “Bren-ji,” she called out to him. “Are you all right?”

The limp showed. His hair was flying loose from its braid and there was dust and fur and spit on his coat. “Fine, nadi-ji. Was it a good flight?”

“Long,” she said, overtaking him in a handful of double steps a human would struggle to make. “Did you fall, Bren-ji? You didn’tfall off…”

“No, just sore. Perfectly ordinary.” He made a determined effort not to limp the rest of the way up the stairs, and went beside her down the hall… which was supposing she wanted the company of sweat and mecheita fur. Jago smelled of flowers, quite nicely so. He’d never noticed it before; and he was marginally embarrassed—not polite to sweat, the word had passed discreetly from paidhi to paidhi. Overheated humans smelled different, and different was not good with atevi, in matters of personal hygiene; the administration had pounded that concept into junior administrative heads. So he tried to keep as discreetly as possible apart from Jago, glad she was back, wishing he might have a chance for a bath before debriefing, and wishing most of all that she’d been here last night. “Where’s Banichi? Do you know? I haven’t seen him since yesterday.”

“He was down at the airport half an hour ago,” Jago said. “He was talking to some television people. I think they’re coming up here.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know, nadi. They came in on the flight. It could have to do with the assassination attempt. They didn’t say.”

Not his business, he concluded. Banichi would handle it with his usual discretion, probably put them on the next flight out.

“Not any other trouble here?”

“Only with Banichi.”

“How?”

“Just not happy with me. I seem to have done something or said something, nadi-ji—I’m not even sure.”

“It isn’t a comfortable business,” Jago said, “to report an associate to his disgrace. Give him room, nand’ paidhi. Some things aren’t within your office.”

“I understand that,” he said, telling himself he hadn’t understood: he’d been unreasonably focussed on his own discomforts last night, to the exclusion of Banichi’s own reasonable distress. It began to dawn on him that Banichi might have wanted things of him he just hadn’t given, before they’d parted in discomfort with each other. “I think I was very rude last night, nadi. I shouldn’t have been. I wasn’t doing my job. I think he’s right to be upset with me. I hope you can explain to him.”

“You haveno ‘job’ toward him, Bren-ji. Ours is toward you. And I much doubt he took offense. If he allowed you to see his distress, count it for a compliment to you.”

Unusual notion. One part of his brain went ransacking memory, turning over old references. Another part went on vacation, wondering if it meant Banichi did after all likehim.

And the sensible, workaday part of his brain told the other two parts to pay attention to business and quit expecting human responses out of atevi minds. Jago meant what Jago said, point, endit; Banichi let down his guard with him, Banichi was pissed about a dirty business, and neither Banichi nor Jago was suddenly, by being cooped up with a bored human, about to break out in human sentiment. It wasn’t contagious, it wasn’t transferable, and probably he frustrated hell out of Banichi, too, who’d just as busily sent him clues he hadn’t picked up on. As a dinner date, he’d been a dismal substitute for Jago, who’d been off explaining to the Guild why somebody wanted to kill the paidhi; and probably by the end of the evening, Banichi had ideas of his own why that could be.

They reached the door. He had his key from his pocket, but Jago was first with hers, and let them into the receiving room.

“So glum,” she said, looking back at him. “Why, nand’ paidhi?”

“Last night. We were saying things—I wished I hadn’t. I wish I’d said I was sorry. If you could convey to him that I am…”

“Said and did aren’t even brothers,” Jago said. She pulled the door to, pocketed her key and took the portfolio from under her arm. “This should cheer you. I brought your mail.”

He’d given up. He’d accepted that it wasn’t going to get through security; and Jago threw over all his suppositions about his situation in Malguri.

He took the bundle she handed him and sorted through it, not even troubling to sit down in his search for personal mail.

It was mostly catalogs, not nearly so many as he ordinarily got; three letters, but none from Mospheira—two from committee heads in Agriculture and Finance, and one with Tabini’s official seal.

It wasn’tall his mail, not, at least, his ordinary mail—nothing from Barb or his mother. No communication from his office, messages like, Where are you? Are you alive?

Jago surely knew what was missing. She had to know, she wasn’t that inefficient. And what did he say about it? She stood there, waiting, probably in curiosity about Tabini’s letter.

Or maybe knowing very well what was in it.

He began to be scared of the answers—scared of his own ignorance and his own failure to figure out what the silence around him was saying, or what of Tabini’s signals he was supposed to have picked up.

He ran his thumbnail under the seal on Tabini’s letter, hoping for rescue, hopingit held some sort of explanation that didn’t add up to disaster.

Tabini’s handwriting—was not the clearest hand he had ever dealt with. The usual declaration of titles. I hope for your health, it began, with Tabini’s calligraphic flourish. I hope for your enjoyment of Malguri’s resources of sun and water.

Thanks, Tabini, he thought sourly, thanks a lot. The rainy season, no less. He rested a sore backside against the table to read it, while Jago waited.

Something about television. Television, for God’s sake.

… my intention by this interview to give people around the world an exposure to human thought and appearance far different than the machimi have presented. I feel this is a useful opportunity which should not be wasted, and have great confidence in your diplomacy, Bren. Please be as frank with these professionals as you would be with me, privately.

“Nadi Jago. Do you know what’s in this?”

“No, Bren-ji. Is there a problem?”

“Tabini’s sent the television crew!”

“That would explain the people on the flight. I am surprised we weren’t advised. Though I’m sure they have credentials.”

Under the circumstances which have made advisable your isolation from the City and its contacts, I can think of no more effective counter to your enemy than the cultivation of increased public favor. I have spoken personally to the head of news and public awareness at the national network, and authorized a reputable and highly regarded news crew to meet with you at Malguri, for an interview which may, in my hopes and those of the esteemed lord Minister of Education, lead to monthly news conferences…

“He wants me to do a monthly news program! Do you knowabout this?”

“I plead not, nadi-ji. I’m sure, however, if Tabini-aiji has cleared these individuals to speak to you, they’re very reputable people.”

“Reputable people.” He scanned the letter for more devastating news, found only I know the weather in this season is not the best, but I hope that you have found pleasure in the library and accommodation with the esteemed aiji-dowager, to whom I hope you will convey my personal good wishes.

“This is impossible. I have to talk to Tabini.—Jago, I need a phone. Now.”

“I’ve no authorization, Bren-ji. There isn’ta phone here, and I’ve no authorization to remove you from our—”

“The hell, Jago!”

“I’ve no authorization, Bren-ji.”

“Does Banichi?”

“I doubt so, nadi-ji.”

“Well, neither do I. I can’t talk to these people.”

Jago’s frown grew anxious. “The paidhi tells me that Tabini-aiji has authorized these people. If Tabini-aiji has authorized this interview, the paidhi is surely aware that it would be a very great embarrassment to these people and their superior, extending even to the aiji’s court. If the paidhi has any authorization in this letter to refuse this, I must ask to see this letter.”

“It’s not Tabini. I’ve no authorization from Mospheira to do any interview. I absolutely can’t do this without contacting my office. I certainly can’t do it on any half-hour notice. I need to contact my office. Immediately.”

“Is not your man’chito Tabini? Is this not what you said?”

God, rightdown the predictable and unarguable slot.

“My man’chito Tabini doesn’t exclude my arguing with him or my protecting my position of authority among my own people. It’s my obligation to do that, nadi-ji. I have no force to use. It’s all on your side. But my man’chigives me the moral authority to call on you to do my job.”

The twists and turns of a trial lawyer were a necessary part of the paidhi’s job. But persuading Jago to reinterpret man’chiwas like pleading a brief against gravity.

“Banichi would have to authorize it,” Jago said with perfect composure, “if he has the authority, which I don’t think he does, Bren-ji. If you wish me to go down to the airport, I will tell him your objection, though I fear the television crew will come when their clearance says to come, which may be before any other thing can be arranged, and I cannot conceive how Tabini could withdraw a permission he seems to have granted without—”

“I feel faint. It must be the tea.”

“ Please, nadi, don’t joke.”

“I can’t deal with them!”

“This would reflect very badly on many people, nadi. Surely you understand—”

“I cannot decide such policy changes on my own, Jago! It’s not in the authority I was given—”

“Refusal of these people must necessarily have far-reaching effect. I could not possibly predict, Bren-ji, but can you not comply at least in form? This surely won’t air immediately, and if there should be policy considerations, surely there could be ameliorations. Tabini has recommended these people. Reputations are assuredly at stake in this.”

Jago was no mean lawyer herself—versed in man’chiand its obligations, at least, and the niceties on which her profession accepted or didn’t accept grievances. Life and death. Justified and not. And she had a point. She had serious points.

“May I see the letter, Bren-ji? I don’t, of course, insist on it, but it would make matters clearer.”

He handed it over, Jago walked over to the window to read it, not, he thought, because she needed the light.

“I believe,” she said, “you’re urged to be very frank with these people, nadi. I think I understand Tabini-aiji’s thinking, if I may be so forward. If anything should happen to you—it would be very useful to have popular sympathy.”

“If anything should happen to me.”

“Not fatally. But we have taken an atevi life.”

He stood stock still, hearing from Jago what he thought he heard. It was her impeccable honesty. She could not perceive that there was prejudice in what she said. She was thinking atevi politics. That was her job, for Tabini and for him.

“An atevi life.”

“We’ve taken it in defense of yours, nand’ paidhi. It’s our man’chito have done so. But not everyone would agree with that choice.”

He had to ask. “Do you, nadi?”

Jago delayed her answer a moment. She folded the letter. “For Tabini’s sake I certainly would agree. May I keep this in file, nadi?”

“Yes,” he said, and shoved the affront out of his mind. What did you expect? he asked himself, and asked himself what was he to do without consultation, what might they ask and what dared he say?

Jago simply took the letter and left, through his bedroom, without answering his question.

An honest woman, Jago was, and she’d given him no grounds at all to question her protection. It wasn’t precisely what he’d questioned—but she doubtless didn’t see it that way.

He’d alienated Banichi and now he’d offended Jago. He wasn’t doing well at all today.

“Jago,” he called after her. “Are you going down to the airport?”

Atevi manners didn’t approve yelling at people, either. Jago walked all the way back to answer him.

“If you wish. But what I read in the letter gives me little grounds on which to delay these people, nand’ paidhi. I can only advise Banichi of your feelings. I don’t see how I could do otherwise.”

He was at the end of his resources. He made a small, weary bow. “About what I said. I’m tired, nadi, I didn’t express myself well.”

“I take no offense, Bren-ji. The opinion of these people is uninformed. Shall I attempt to reach Banichi?”

“No,” he said in despair. “No. I’ll deal with them. Only suggest to Tabini on my behalf that he’s put me in a position which may cost me my job.”

“I’ll certainly convey that,” Jago said. And if Jago said it that way, he did believe it.

“Thank you, nadi,” he said, and Jago bowed and went on through the bedroom.

He followed, with a vacation advertisement and a crafts catalog, which he figured for bathtub reading.

Goodbye to the hour-long bath. He rang for Djinana to advise him of the change in plans, he shed the coat in the bedroom, limped down the hall into the bathroom and shed dusty, spit-stained clothes in the hamper on the way to the waiting tub.

The water was hot, frothed with herbs, and he would have cheerfully spent half the day in it, if Djinana would only keep pouring in warm water. He drowned the crafts catalog, falling asleep in mid-scan—just dropped his hand and soaked it: he found himself that tired and that little in possession of his faculties.

But of course Tano came in to say a van had pulled up in the portico, and it was television people, with Banichi, and they were going to set up downstairs. Would the paidhi care to dress?

The paidhi would care to drown, rather than put on court formality and that damned tailored coat, but Tabini had other plans.

He’d not brought his notes on the transportation problems. He thought he should have. It went to question after question, until at least numbness had set in where he met the chair and where an empty stomach protested the lack of lunch.

“What,” the interviewer asked then, “determines the rate of turnover of information? Isn’t it true that all these systems exist on Mospheira?”

“Many do.”

“What wouldn’t?”

“We don’t use as much rail. Local air is easier. The interior elevations make air more practical for us.”

“But you didn’t present that as an option to the aiji two hundred years ago.”

“We frankly worried that we’d be attacked.”

“So there areother considerations than the environment.”

Sharp interviewer. And empowered by someone to ask questions that might not make the broadcast, but—might, still. Tabini had confidence in this man, and sent him.

“There’s also the risk,” he said, “of creating problems among atevi. You had rail—you almost had rail at the time of the Landing. If we’d thrown air travel into Shejidan immediately, it might have provoked disturbances among the outlying Associations. Not everyone believed Barjida-aiji would share the technology. And better steam trains were a lot less threatening. We could have turned over rockets. We could have said, in the very first negotiations—here’s the formula for dynamite. And maybe irresponsible people would have decided to drop explosives on each other’s cities. We’d just been through a war. It was hard enough to get it stopped. We didn’t want to provide new weapons for another one. Wecould have dropped explosives from planes, when we built them. But we didn’t want to do that.”

“That’s a good point,” the interviewer said.

He hoped it was. He hoped people thought about it.

“We don’t ever want a war,” he said. “We didn’t have much choice about being on this planet. We caused harm we didn’t intend or want. It seems a fair repayment, what the Treaty asked.”

“Is there a limit to what you’ll turn over?”

He shook his head. “No.”

“What about highways?”

Damn, thatquestion again. He drew a breath to think about it. “Certainly I’ve seen the realities of transportation in the mountains. I intend to take my observations to ourcouncil. And I’m sure the nai-aijiin will have recommendations to me, too.”

A little laughter at that. And a sober next question: “Yet you alone, rather than the legislature, determine whether a town gets the transport it needs.”

“Not myself alone. In consultation with the aiji, with the councils, with the legislatures.”

“Why not road development?”

“Because—”

Because mecheiti followed the leader. Because Babs was the leader, and Nokhada hadn’t a choice, without fighting that Nokhada didn’t want, damned stupid idea, and he had to say something to that question, something that didn’t insult atevi.

“Because,” he said, trapped. “We couldn’t predict what might happen. Because we saw the difficulties of regulation.” He panicked. He was losing the threads of it, not making sense, and not making sense sounded like a lie. “We feared at the outset the allocation of road funds might cause division within the Association. A breakdown of an authority we didn’t understand.”

The interviewer hesitated, politely expressionless. “Are you saying, nand’ paidhi, that this policy was based on misapprehension?”

Oh, God. “Initially, perhaps.” The mind snapped back into focus. The villageproblem was the atevi concern. “But we don’t think it would have led to a solution for the villages. Ifthere’d been highways a hundred, two hundred years ago, there’d have been a growth in unregulated commerce. If thathad happened—the commercial interests would build where the biggest highways were, and the straighter the highways, the more big population centers in a row, the more attraction they’d be—while no one but the aiji would have defended the remote villages, who stillwould have trouble getting transportation, very much what we have now, but we’d also have the pollution from the motors and the concentration of even more political power into the major population strings, along those roads. I see a place for a road system—in the villages, not the population centers, as spur lines to the centralized transport system.”

He didn’t engage the interviewer’s interest. He’d gotten too detailed, too technical, or at least promised to lead to technical matters the interviewer didn’t want or felt his audience didn’t want. He sensed the shift in intention, as the interviewer shifted position and frowned. He was glad of it. The interviewer posed a few more questions, about where he lived, about family associations, about what he did on vacation, thank God, none of them critical. He was sweating under the lights when the interview wound to its close and the interviewer went through the obligatory courtesies.

‘Thank you, nand’ paidhi,“ the man said, and Bren withheld the sigh of relief as the lights went out.

“I’m sorry,” he said at once, “I’m not used to cameras. I’m afraid I wasn’t very coherent at all.”

“You speak very well, nand’ paidhi, muchbetter than some of our assignments, I assure you. We’re very pleased you found the time for us.” The interviewer stood up, he stood up, Banichi stood up, from the shadowed fringes, where the lights had obscured his presence. Everyone bowed. The interviewer offered a hand to shake. Someone must have told him that.

“You’ve been informed on our customs,” he ventured to say, and the interviewer was pleased and bowed, shaking hands with a crushing grip.

There was the commercial plane returning at sunset. The news crew had another assignment in Maidingi, on the electrical outage. Thank God. The crew was packing up lights, disconnecting cable run like an infestation of red and black vines across the ancient carpets, from the remote hallways. Maigi went to retrieve the far end somewhere near the kitchens, where, Bren was sure, the staff was not eager to admit strangers. Everything folded away into boxes, The glass-eyed animals stared back from the walls, as amazed and dazed as the paidhi.

What have I done? he asked himself, asked himself if he could justify everything he’d said, when he wrote his report to Mospheira, but they’d kept off sensitive topics—he’d accomplished that much, give or take his mental lapse on the highway question.