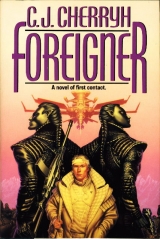

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

“Bren-ji.”

A second touch. He blinked at a black, yellow-eyed face, a warm and worried face.

“Jago!”

“Bren-ji, Bren-ji, you have to leave this province. Some people have come into Maidingi, following rumors—the same who’ve acted against you. We need to get you out of here, now—for your protection, and theirs. Far too many innocents, Bren-ji. We’ve received advisement from the aiji-dowager, from her people inside the rebel movement… certain of them will take her orders. Certain of that group she knows will not. The aijiin of two provinces are in rebellion—they’ve sent forces to come up the road and take you from Malguri.” The back of her fingers brushed his cheek a third time, her yellow eyes held him paralyzed. “We’ll hold them by what tactics we can use. Rely on Ilisidi. We’ll join you if we can.”

“Jago?”

“I’ve got to go. Gotto go, Bren-ji.”

He tried to delay her to ask where Banichi was or what they meant by hold them—but her fingers slipped through his, and Jago was away and out the door, her black braid swinging.

Alarm brought him to his feet—sore joints, headache, and lapful of blankets and all—with half that Jago had said ringing and rattling around a dazed and exhausted brain.

Hold them? Hold a mob off from Malguri? How in hell, Jago?

And for what? One damned more illusion, Jago? Is thisone real?

Innocents, Jago said.

People who wanted to kill him? Innocents?

People who were just scared, because the word had begun to spread of what had arrived in their skies. Malguri was still candle-lit and fire-lit. The countryside around about had had no lights. People in cities didn’t spend their time on rooftops looking at a station you couldn’t see in city haze without a telescope, no, but a quarter of Maidingi township had been in blackout, and ordinary atevi could have had pointed out to them what astronomers and amateurs would have seen in their telescopes days ago,

Now the panic began, the fear of landings, the rumor of attack on their planet from an enemy above their reach.

What were they to think of this apparition, absent a communication from the paidhi’s office, but a resumption of the War, another invasion, another, harsher imposition of human ways on the world? They’d had their experience of humans seeking a foothold in their territory.

He stood lost in the middle of a nightmare—realized Ilisidi’s guards were watching him anxiously, and didn’t know what to do, except that the paidhi was the only voice, the onlyvoice that could represent atevi interests to Mospheira’s authorities—and to that ship up there.

No contact, the Guild had argued; but that principle had fallen in the first stiff challenge. To get the deal they wanted out of the station… to go on getting the means to search for Earth, they’d given in and allowed the initial personnel and equipment drops.

And two hundred years now from the War of the Landing, what did any human on earth know… but this world, and a way of life they’d gotten used to, and neighbors they’d reached at least a hope of understanding at distance?

Damn, he thought, angry, outragedat the intrusion over their heads, and he didn’t imagine that there was overmuch joy in Mospheira’s conversations with the ship, either.

Charges and counter-charges. Charges his office could answer with some authority—but when Phoenixasked, Where isthis interpreter, where is the paidhi-aiji, what opinion does hehold and why can’t we find him?… what could Mospheira say? Sorry—we don’t know?

Sorry, we’ve never lost track of him before?

And couldn’t the Commission office, knowing what they knew, realize that, with that ship appearing in the skies, they’d better callhis office in Shejidan? Or realize, if their call didn’t go through, that he was in trouble, that atevi knew what was going on, and that he might be undergoing interrogation somewhere?

Damned right, Hanks knew. Deana Nuke-the-Opposition Hankswas making decisions in his name on Mospheira, because he was out of touch.

He needed a phone, a radio, anything. “I have to talk to my own security,” he said, “about that ship up there. Please, nadiin, can you send someone to bring Jago back, or Banichi… anyone of my staff? I’ll talk to Cenedi. Or the dowager.”

“I fear not, nand’ paidhi. Things are moving very quickly now. Someone’s gone for your coat and for heavier clothes. If you’d care for breakfast…”

“My coat. Where are we going, nadiin? Whenare we going? I need to get to a phone or a radio. I need to reach my office. It’s extremely important they know that I’m all right. Someone could take very stupid, very dangerous actions, nadiin!”

“We can present your request to Cenedi,” Giri said. “In the meantime, the water’s already hot, nand’ paidhi. Tea can be ready in a very small moment. Breakfast is waiting. We would very much advise you to have breakfast now. Please, nand’ paidhi. I’ll personally take your request to Cenedi.”

He couldn’t get more than that. The chill was back, a sudden attack of cold and weakness that told him Giri was giving him good advice. He’d gone to see Cenedi last night before supper. His stomach was hollow to the backbone.

And if they’d kept breakfast waiting and water hot since his meeting with Ilisidi, it wasn’t that they meant to take the usual gracious forever about bringing it.

“All right,” he said. “Breakfast. But tell the dowager!”

Giri disappeared. The other guard stood where he’d been standing, and Bren strayed back to the fireside, with his hair inching loose again, falling about his shoulders. His clothes were smudged with dust from the cellars. His shirt was torn about the front, somewhere in the exchange—most likely in his escape attempt, he thought. It wasn’t humanity’s finest hour. Atevi around him, no matter the sleep they’d missed, too, looked impervious to dirt and exhaustion, impeccably braided, absolutely ramrod straight in their bearing. He lifted sore arms, both of them, this time, wincing with the effort, and separating his tangled hair, braided three or four turns to keep it out of his face—God knew what had happened to the clip. He’d probably lost it on the stairs outside. If they went out that way he might find it.

A servant carried in a heavy tray with a breakfast of fish, cheese, and stone-ground bread, along with a demi-pot of strong black tea, and set it on a small side table for him. He sat down to it with better appetite than he’d thought he could possibly find, in the savory smell and the recollection of Giri’s warning that meals might not be on schedule again… which, with the business about getting his coat, meant they were going to take action to get him out, maybe throughthe opposition down in Maidingi… on Ilisidi’s authority, it might be.

But breaking through a determined mob was a scary prospect. Trust an atevi lord to know how far he or she could push… atevi had that down to an art form.

Still, a mob under agitation might not respect the aiji-dowager. He gathered that Ilisidi had been with them and changed her mind last night; and if she tried to lie or threaten her way through a mob who might be perfectly content with assassinating the paidhi, there could well be shooting. A large enough mob could stop the van.

In which case the last night could turn out to be only a taste of what humanity’s radical opposition might do to him if it got its hands on him. If things got out of hand, and they couldn’t get to a plane—he could end up shot dead before today ended, himself, Ilisidi, God knew who else… and that could be a lot better than the alternative.

He ate his breakfast, drank his tea, and argued with himself that Cenedi knew what he was doing, at least. A man in Cenedi’s business didn’t get that many gray hairs or command the security of someone of Ilisidi’s rank without a certain finesse, and without a good sense of what he could get away with—legally and otherwise.

But he wanted Banichi and Jago, dammit, and if some political decision or Cenedi’s position with Ilisidi had meant Banichi and Jago had drawn the nasty end of the plan—

If he lost them…

“Nand’ paidhi.”

He turned about in the chair, surprised and heartened by a familiar voice, Djinana had come with his coat and what looked like a change of clothes, his personal kit and, thank God, his computer—whether Djinana had thought of it, whether Banichi or Jago had told him, or whoever had thought of it, it wasn’t going to lie there with everything it held for atevi to find and interpret out of context, and he wasn’t going to have to ask for it and plead for it back from Cenedi’s possession.

“Djinana-ji,” he said, with the appalled realization that if he was leaving and getting to safety this morning, Malguri’s staff wouldn’t have that option, not the servants whose man’chibelonged to Malguri itself. “They’re saying people down in Maidingi are coming up here looking for me. That two aijiin are supporting an attack on Malguri. You surely won’t try to deal with this yourselves, nadi. Capable as you may be—”

Djinana laid his load on the table. “The staff has no intention of surrendering Malguri to any ill-advised rabble.” Djinana whisked out a comb and brush from his kit, and came to his chair. “Forgive me, nand’ paidhi, please continue your breakfast—but they’re in some little hurry, and I can fix this.”

“You’re worth more than stones, Djinana!”

“Please.” Djinana pushed him about in the chair, pushed his head forward and brushed with a vengeance, then braided a neat, quick braid, while he ate a piece of bread gone too dry in his mouth and washed it down with bitter tea,

“Nadi-ji, did you know why they brought me here? Did you know about the ship? Doyou understand, it’s not an attack, it’s not aimed at you.”

“I knew. I knew they suspected that you had the answer to it.—And I knew very soon that you would never be our enemy, paidhi-ji.” Djinana had a clip from somewhere—the man was never at a loss. Djinana finished the braid, brushed off his shoulders, and went and took up his coat. “There’s no time to change clothes, I fear, and best you wait until you’re on the plane. I’ve packed warm clothing for a change this evening.”

He got up from the chair, turned his back to Djinana, and toward the window. “Are they sending a van up?”

“No, paidhi-ji. A number of people are on their way up here now, I hear, on buses. I truly don’t think they’re the ones to fear. But you’re in very good hands. Do as they say.” Djinana shoved him about by the shoulder, helped him on with the coat, and straightened his braid over the collar. “There. You look the gentleman, nadi. Perhaps you’ll come back to Malguri. Tell the aiji the staff demands it.”

“Djinana,—” One couldn’t even say I like. “I’ll certainly tell him that. Please, thank everyone in my name.” He went so far as to touch Djinana’s arm. “Please see that you’re here when I come visiting, or I’ll be greatly distressed.”

That seemed to please Djinana, who nodded and quietly took his leave past a disturbance in the next room—Ilisidi’s voice, insisting, “They won’t lay a hand on me!”

And Cenedi’s, likewise determined:

“ ’Sidi-ji, we’re getting out, damned if they won’t come inside! Shut up and get your coat!”

“Cenedi, it’s quite enough to remove him out of range…”

“Giri, get ’Sidi’s coat! Now!”

The guards’ eyes had shifted in that direction. Nothing of their stance had altered. He gathered up his change of clothes and wrapped it about his computer, waiting with that in his arms and his kit in his hand, listening as Cenedi gave orders for the locking of doors and the extinguishing of fires.

But Djinana’s voice, distantly, said that the staff would see to those matters, that they should go, quickly, please, and take the paidhi to safety.

He stood there, the center of everyone’s difficulty, the reason for the danger to Malguri. He felt that the absolute least he could do was put himself conveniently where they wanted him. He supposed that they would go out through the hall and down; he ventured as far as the door to the reception room, but Cenedi burst through that door headed in the opposite direction, bringing Ilisidi with him, on a clear course toward the rearmost of Ilisidi’s rooms, with a number of guards following.

“Where’s Banichi?” he tried to ask as they went through the bedroom, with the guards trailing him, but Cenedi was arguing with Ilisidi, hastening her on through the hallways at the back of the apartments, to a back stairs. A man he thought he recognized from last night stood at the landing, holding a weapon he didn’tknow, shoving shells into the butt from a box on the post of the stairs.

That gun wasn’t supposed to exist. He had never seen that man on staff in Malguri. Banichi and Jago, and presumably Tano and Algini, with them, had gone somewhere he didn’t know, a mob wanted to turn him over to rebels against Tabini—and they were bound down to the back side of Malguri, down, he realized as Cenedi and Ilisidi opened the doors onto shadowed stone—to a stairway beside the stable, where the hisses and grumbling of mecheiti out in the courtyard told him howthey were leaving Malguri, unless they were taking this route only to divert pursuit—

This is mad, he thought as they came out onto the landing overlooking the courtyard, seeing that the mecheiti were rigged out in all their gear, with, moreover, saddle packs and other accoutrements they’d never used on their morning rides.

This isn’t two hundred years ago. They’ve planes, they’ve guns like that one back on the stairs…

Something exploded, shaking the stones, a vibration that went straight to his knees and his gut. Someone wasn’t waiting for the mob in the buses.

“Come on!” Cenedi yelled up at them from the courtyard, and he hurried down the steps, with some of Cenedi’s men behind him, and the handlers trying to get the mecheiti sorted out.

It was a crazed plan. Reason told him it was beyond lunacy to take out across the country like this. There was the lake. They might have arranged a boat across to another province.

If the provinces across the lake weren’t the ones in rebellion,

A second explosion hammered at the stones. Itisidi looked back and up, and swore; but Cenedi grabbed her arm and hurried her along where handlers held Babs waiting.

He spotted Nokhada, darted, arms encumbered, among the towering, shifting bodies; and wondered how he was to load the saddle packs with his bundled clothes and the computer, but the handlers took his belongings from him.

“Careful!” he said, wincing as the handler almost dropped the computer, the weight of which he hadn’t anticipated. His computer went into one bag, the clothes and the kit went into the other, on the other side of Nokhada’s lean and lofty rump, Nokhada fidgeting and fighting the rein. The mecheiti this morning all had a glimmer of brass about the jaw, not blunt caps on the rooting-tusks, but a sharp-pointed fitting he’d seen only in machimi—brass to protect the tusks.

In war.

It was surreal. The fighting-brass was, with Nokhada’s head-butting tendencies, not a weapon he wanted to argue with or even stay on the ground with. He took the rein one handler gave him, couldn’t manage it with the sore arm, shifted hands and hit Nokhada with his fist, trying to make the creature drop a shoulder. Riders all around him were already up. Nokhada objected, fidgeted up again, and resisted a second order, circling him, wild-eyed in all the surrounding haste and excitement. Thatwas how things were going to go, he thought, unsure he could restrain the creature in an emergency—scared of its strength and that jaw as he hadn’t been since the first.

“Nadi,” a handler said, offering a hand, and atevi strength snared and held the rein.

He grabbed the mounting-strap, relied on the unceremonious shove of the handlers, shoved his foot in the stirrup on the way up and landed, sore-boned, and with a wrench of his sore shoulders, on the pad, with his heart pounding. He took a quick fistful of rein to bring Nokhada under control in the general confusion, as someone opened the outward gate.

Cold morning wind blasted through the court, stinging his face as all the mecheiti began to move. He looked distractedly for Babs and Ilisidi. He brought Nokhada another circle, and Nokhada found a fix on Babs before he even saw Ilisidi.

He couldn’thold Nokhada, then, with Babs headed for the gate. Nokhada shouldered other mecheiti and struck a loping pace in Babs’ wake, into the teeth of an incoming gust that felt like a wall of ice.

The arch passed around him as a blur of shadow and stone. The vast gray of the lake was a momentary, giddy nothingness first in front of him and then at his right as Nokhada veered sharply along the edge and up the mountainside.

Follow Babs to hell, Nokhada would.

XII

« ^ »

It was across the mountainside, and up and up the brushy slope, across the gully, the very course he’d bashed his lip taking, the first time he’d ridden after Ilisidi.

And ten or so of Ilisidi’s guard, when he snatched a glance back on the uphill, were right behind him… along with a half a dozen saddled but riderless mecheiti.

They’d turned out the whole stable to follow, leaving nothing for anyone to use catching them—he knew that trick from the machimi. He found himself ina machimi, war-gear and armed riders and all of it. It only wanted the banners and the lances… no place for a human, he kept thinking. He didn’t know how to manage Nokhada if they had to break through a mob, he didn’t know whether he could even stay on if they took any harder obstacles.

And ride across a continent to reach Shejidan? Not damned likely.

Jago had said believe Ilisidi. Djinana had said believe Cenedi.

But they were headed to the north and west, cut off, by the sound of the explosions, from the airport—cut off from communications, from his own staff, from everything and everyone of any resource he knew, unless Tabini was sending forces into Maidingi province to get possession of the airport—which the rebels held.

Which meant the rebels could go by air—while they went at whatever pace mecheiti flesh and bone could sustain. The rebels could track them, harass them as they liked, on the ground and from the air.

Only hope they hadn’t planes rigged to let them shoot at targets. Damned right they could think of it—no damned biichi-giabout it: Mospheira had designed atevi planes to make that modification as difficult as possible—they’d stuck to fixed-wing and generally faster aircraft, but it couldn’t preclude some atevi with a reason putting his mind to it. Finesse, he’d heard it said in the machimi, didn’t apply in war—and war was what two rebel aijiin were trying to start here.

Push Tabini to the brink, break up the Western Association and reform it around some other leader—like Ilisidi?

And she, twice passed over by the hasdrawad, was double-crossing the rebels?

Dared he believethat?

An explosion echoed off Malguri’s walls.

He risked a second glance back and saw a plume of smoke going up until the wind whipped it completely away over the western wall. That was inside, he thought with a rising sense of panic, and as he swung his head about, he saw the crest of the ridge ahead of them, looming up with its promise of safety from weapons-fire that might come up at them from Malguri’s grounds.

And maybe their disappearance over that ridge would stopthe attack on Malguri, if the staff could convince a mob and armed professionals they weren’t there—God help Djinana and Maighi, who had never asked to be fighters, who had strangers like that man with the gun standing on the stairway, people Ilisidi and Cenedi must have brought in… people who might not put Malguri’s historic walls at such a high premium.

Cold blurred his eyes. The shooting pains in his shoulders took on a steady rhythm in Nokhada’s lurching climb. There was one craggy knoll between them and sharpshooters that might be trying to set up outside Malguri’s mountain ward walls—but Banichi and Jago were seeing to that, he told himself so. Brush and rock came up in front of them, then blue sky. Perspective went crazy for a moment as first Ilisidi and Cenedi went over the edge and then Nokhada nosed down and plunged down the other side, a giddy, intoxicating flurry of strides down a landscape of rough rock and scrub that his subconscious painted snow-white and sanity jerked into browns and earth again. Pain rode the jolts of Nokhada’s footfalls—torn joints, sore muscles, hands and legs losing feeling in the cold.

No damned place to take a fall. He suffered a moment of panic, then feltthe mountain, God save his neck—Nokhada ran with the same logic and the same necessities as he knew, and he clenched the holding strap in his good hand and wrapped the rein into the fingers of the weaker one, beginning to take the wind in his face with an adrenaline rush, hyper-awareness of the slope and whereNokhada’s feet had to touch, however briefly, to make the next stride.

He was plotting a course down the mountain, drunk on understanding, that was the crazed part, his eye saw the course and his heart was racing. His ears felt the shock an explosion made, but it was distant and he was hellbent for catching the riders ahead of him—not sane. Not responsible. Enjoyingit. He’d damned near caught up to Ilisidi when Babs gave a whip of the tail and took a course that Nokhada nearly killed them both trying to reach.

“ ’ Sidi!” he heard Cenedi yell at their backs behind them.

He suffered a second of sane, cold panic, realizing that he’d maneuvered past Cenedi and Ilisidi knewhe was at her tail.

A rock exploded near them, just blew up as it sat on the hillside. Babs took the slot beside a narrow waterfall and struck out uphill among stones the size of houses, higher and higher into the mountains.

Sniper, sanity said. They were still in range.

But he followed Ilisidi, slower now, more sheltered among the boulders, and he had time and breath to realize the foolishness he’d just committed, that he’d pushed himself next behind Ilisidi, that Cenedi was at his back, and that Nokhada was sensibly unwilling to slow down now and lose momentum on the uphill climb.

Fool, he thought. He’d lost his good sense on the mountain. Knowing the responsibility he carried, he’d risked his neck becausehe carried it, and because of the things he couldn’t do and didn’t have, and he didn’t care, didn’t damned well care, during those few selfish highspeed minutes that were nothing but now, risking his life, damn them all, damn Tabini, damn the atevi, damn his mother, Toby, Barb, and the whole human race.

He could have died. He could easily have died in that crazed course. And he discovered so much bitter, secret anger in him—so much rage he shook with it, while Nokhada’s saner, more reasoned strides carried him up and up among the protecting rocks. What sent him down a mountain wasn’t, then, the delirious freedom he told himself it was, it was what he’d just experienced: a spiteful, irrational death wish, aiming his own destruction at everyone and everything he served– thatwas what he was courting.

Not damned fair. The only thing in his life he enjoyed with complete abandon. And it was a damned death wish.

He hated the pressures at home on Mospheira, the job-generated pressures and most of all the emotional, human ones. At the moment he hated atevi, at least in the abstract, he hated their passionless violence and the lies and the endless, schizophrenic analysis he had to do, among them, of every conclusion, every emotion, every feeling he owned, just to decide whether it came of human hardwiring or logical processing.

And most of all he hated hurting for people who didn’t hurt back. He didn’t trust his feelings any longer. He was drained, he was exhausted, he hurt, and he wasn’t dealing with either reality sanely anymore.

It was the second personal truth he’d faced—since that dark moment with the gun at his head. It told him that the paidhi wasn’t handling the job stress. That the paidhi was scared as hell and not sure of the people around him, and no longer sure he’d done the right thing in anything he’d done.

You didn’t know, you didn’t damned well knowwith atevi, what went on at gut level, on any given point, not because you couldn’t translate it, but because you couldn’t feel it, couldn’t resonate to it, couldn’t remotely guess what it felt like inside.

They were on the verge of war, atevi were shooting each other over what to do about humans, and the paidhi was coming apart—they’d taken too much away from him last night. Maybe they hadn’t meant to do it, maybe they didn’t know they’d done it, and he could reason with himself, he knew all the psychological labels: that there was too much unresolved, that there were even physiological reasons behind the sudden fit of chill and fear and the morbid self-dissection this morning that had their only origins in the business last night.

And, no, they’d notbeen playing games last night. It had never been a false threat they’d posed; Cenedi was damned good at what he did, and Cenedi hadn’t weighed his mental condition heavily against the answers Cenedi had to have.

It didn’t change the fact they’d shaken things loose inside—ricochets that were still racketing about a psyche that hadn’t been all that steady to start with.

He couldn’t afford to break. Not now. Ignore the introspection and figure out the minimal things he was going to tell atevi and humans that would silence the guns and discredit the madmen who wanted this war.

That was what he had to do.

At least the gunshots had stopped coming. They’d passed out of earshot of the explosions, whatever might be happening back at Malguri, and struck a slower, saner pace on easier ground, where they might have run—a more level course, interspersed with sometimes a jolting climb, sometimes a jogging diagonal descent—generally much more to the south now, and only occasionally to the west, which seemed to add up to a slant toward Maidingi Airport, where the worst trouble was.

And maybe to a meeting with help from Tabini, if Tabini had any idea what was happening here… and trust Banichi that Tabini did know, in specifics, if Banichi could get to a phone, or if the radio could reach someone who could get the word across half a continent.

“We’re heading south,” he said to Cenedi, when they came close enough together. “Nadi, are we going to Maidingi?”

“We’ve a rendezvous point on the west road,” Cenedi said. “Just past a place called the Spires. We’ll pick up your staff there, assuming they make it.”

That was a relief. And a negation of some of his suspicions. “And from there?”

“West and north, to a man we think is safe. Watch out, nand’ paidhi!”

They’d run out of space. Cenedi’s mecheita, Tali, forged ahead, making Nokhada throw up her head and back-step. Nokhada gave a snap at Tali’s departing rump, but there was no overtaking her in that narrow space between two room-sized boulders.

Pick up his staff, Cenedi said. He was decidedly relieved on that score. The rest, avoiding the airport, getting to someone who mighthave motorized transport, sounded much more sane than he’d feared Cenedi was up to. Rather than a mapless void, their course began to lie toward points he could guess, toward provinces the other side of the mountains, westward, ultimately—he knew his geography. And firmer than borders could ever be among atevi, where individual towns and houses hazed from one man’chito another, even on the same street—Cenedi knew a definite name, a specific man’chiCenedi said was safe.

Cenedi, in his profession, wasn’t going to make that judgment on a guess. Ilisidi might be double-crossing her associates—but aijiin hadn’ta man’chito anyone higher, that was the nature of what they were: her associates knew it and knew they had to keep her satisfied.

Which they hadn’t, evidently. Tabini had made his play, a wide and even a desperate one, sending the paidhi to Malguri, and letting Ilisidi satisfy her curiosity, ask her questions—running the risk that Ilisidi might in fact deliver him to the opposition. Tabini had evidently been sure of something—perhaps (thinking as atevi and not as a human being) knowing that the rebels couldn’tsatisfy Ilisidi, or meant to double-cross her: never count that Ilisidi wouldn’t smell it in the wind. The woman was too sharp, too astute to be taken in by the number-counters and the fear-merchants… and if he was, personally, the overture Tabini made to her, Ilisidi might have found Tabini’s subtle hint that he foreknew her slippage toward the rebels quite disturbing; and found his tacit offer of peace more attractive at her age than a chancier deal with some ambitious cabal of provincial lords who meant to challenge a human power Tabini might deal with.

A deal with conspirators who might well, in the way of atevi lords, end up attacking each other.

He wasn’t in a position with Ilisidi or Cenedi to ask those critical questions. Things felt touchy as they were. He tried now to keep the company’s hierarchy of importance, always Babs first, Cenedi’s mecheita mostly second, and Nokhada politicking with Cenedi’s Tali for number two spot every time they took to a run, politics that hadn’t anything to do with the motives of their riders, but dangerous if their riders’ personal politics got into it, he had sopped that fact up from the machimi, and knew that he shouldn’t let Nokhada push into that dual association ahead of him, not with the fighting-brass on the tusks. Cenedi wouldn’t thank him, Tali wouldn’t tolerate it, and he had enough to do with the bad arm, just to hold on to Nokhada.

He’d recovered from his insanity, at least by the measure he now had some idea where they were going.

But he daren’t push. He’d gotten Ilisidi’s help, but it was a chancy, conditional support for him and for Tabini that he still daren’t be sure of… never trust that the woman Tabini called ’Sidi-ji wasn’t pursuing some course toward her own advantage, and toward her own power in the Western Association, if not in some other venue.

From one giddy moment to the next, he trusted none of them.

Fourteen words, the language had for betrayal, and one of them doubled for ‘taking the obvious course.’