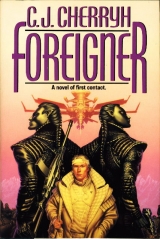

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

IX

« ^ »

Downstairs all the oil lamps were lit and a fire burned in the hearth. The outer hall, with its ancient weapons and its trophy heads and its faded, antique banners, was all golds and browns and faded reds. The upward stairs and the retreating hall below them were cast in shadow, interrupted by circles of lamplight from upstairs and down. Power was still out. Power looked to stay out, this time, and Bren regretted not wearing his coat downstairs. Someone must have had the front door open recently. The whole lower hall was cold.

But he expected no long meeting, no formality, and the fire moderated the chill. He stood warming his hands, waiting—heard someone coming from Ilisidi’s part of the house, and cast a glance toward that recessed, main-floor hallway.

It was indeed Cenedi, dark-uniformed, with sparks of metal about his person, epitome of the Guild-licensed personal bodyguard. He thought that Cenedi would come as far as the fire, and that Cenedi would deliver him some private word and then let him go back to his supper—but Cenedi walked only far enough to catch his eye and beckoned for him to follow.

Follow him—where? Bren asked himself, not as easy about this little shadow-play as about the simple summons downstairs—as difficult to refuse as the rest of Ilisidi’s invitations.

But in this turn of events he had a moment’s impulse to excuse himself upstairs on the pretext of getting his coat, and to send Djinana to find Banichi or Jago—which he knew now he should already have done. Dammit, he said to himself, if he had been half thinking upstairs…

But he no longer knew which side of many sides was dealing in truth tonight—no longer knew for certain how many sides there were. The gun was missing. Someone had it… possibly Cenedi, possibly Banichi. Possibly Banichi had taken it to keep Cenedi from finding it: the chances were too convoluted to figure. If Djinana and Maighi had discovered it and taken it to Cenedi, he believed in his heart of hearts that Djinana could not have faced him without some visible sign of guilt. Not every atevi was as self-controlled as Banichi or Jago.

But while his guards were out and about on whatever business they were pursuing, he had been making his own decisions this far and come to no grief, and if Cenedi did want to talk to him about the gun, best not try to bluff about it and make Cenedi doubt his truthfulness, bottom line. He could take responsibility on himself for it being there. Cenedi had no way of knowing he hadn’t packed the luggage himself. If the paidhi had to leave office in scandal… God knew, it was better than seeing Tabini implicated, and the Association weakened. It was his own mess. He might have to face the consequences of it.

But if Cenedi had the gun and the serial number, surely the aiji-dowager’s personal guard had the means to contact the police and have that gun traced through records– bythe very computers the paidhi had hoped to make a universal convenience. And a lie trying to cover Banichi could make matters worse.

There were just too damn many things out of place: Banichi’s behavior, Jago’s rushing off like that, this man, dead in the driveway, being some old schoolmate of Banichi’s… or whatever licensed assassins called their fellows.

Cenedi at least had missed opportunity after opportunity to fling the paidhi off the mountainside with no one the wiser. The near-fatal tea could have been stronger. If there was something sinister going on within the household, if Tabini had sent him here simply to get Banichi and Jago inside Ilisidi’s defenses—that was his own nightmare scenario—the paidhi was square in the middle of it; he likedIlisidi, dammit, Cenedi had never done him any harm, and what in the name of God had he gotten himself into, coming down here to talk to Cenedi in private? He could lie with an absolutely innocent face when he had an official, canned line to hand out. But he couldn’t lie effectively about things like guns, and whether Banichi was up to anything… he didn’t know any answers, either, but he couldn’t deal with the questions without showing an anxiety that an ateva would read as extreme.

He walked through the circles of lamplight, back and back into the mid-hall where Cenedi stood waiting for him, a tall shadow against the lamplight from an open door, a shadow that disappeared inside before he reached the door.

He expected only Cenedi. Another of Ilisidi’s guards was in the office, a man he’d ridden with that morning. He couldn’t remember the name, and he didn’t know at first, panicked thought what that man should have to do with him.

Cenedi sat down and offered the chair at the side of his desk. “Nand’ paidhi, please.” And with a wry irony: “Would you—I swear to its safety—care for tea?”

One could hardly refuse that courtesy. More, it explained the second man, there to handle the amenities, he supposed, in a discussion Cenedi might not want bruited about outside the office. “Thank you,” he said gratefully, and took the chair, while the guard poured a cup for him and one for Cenedi.

Cenedi dismissed the man then, and the man shut the door as he left. The two oil lamps on the wall behind the desk cast Cenedi’s broad-shouldered shape in exaggerated, overlapping shadows, emitted fumes that made the air heavy, as, one elbow on the desk, one hand occasionally for the teacup, Cenedi sorted through papers on his desk as if those had the reason of the summons and he had lost precisely the one he wanted.

Then Cenedi looked straight at him, a flash of lambent yellow, the quirk of a smile on his face.

“How are you sitting this evening, nand’ paidhi? Any better?”

“Better.” It set him off his guard, made him laugh, a little frayed nerves, there, and he sat on it. Fast

“Only one way to get over it,” Cenedi said, “The dowager’s guard sympathizes, nand’ paidhi. They laugh. But we’ve suffered. Don’t think their humor aimed at you.”

“I didn’t take it so, I assure you.”

“You’ve a fair seat for a beginner. I take it you don’t spend all your time at the desk.”

He was flattered. But not set off his guard a second time. “I spend it on the mountain, when I get the chance. About twice a year.”

“Climbing?”

“Skiing.”

“I’ve not tried that,” Cenedi said, shuffling more paper, trimming up a stack, “I’ve seen it on television.. Some young folk trying it, up in the Bergid. No offense, but I’d rather a live instructor than a picture in a contraband catalog and some promoter’s notion how not to break your neck.”

“Is thatwhere my mail’s been going?”

“Oh, there’s a market for it. The post tries to be careful. But things do slip.”

Is that what this is about? Bren asked himself. Someone stealing mail? Selling illicit catalogs?

“If you get me to the Bergid this winter,” he said, “I’d be glad to show you the basics. Fair trade for the riding lessons.”

Cenedi achieved a final, two-handed stack in his desk-straightening. “I’d like that, nand’ paidhi. On more than one account. I’d like to persuade the dowager back to Shejidan. Malguri is hellin the winter.”

They still hadn’t gotten to the subject. But it wasn’t uncommon in atevi business to meander, to set a tone. Atevi manners.

“Maybe we can do that,” he said, “I’d like to.”

Cenedi sipped his tea and set the cup down. “They don’t ride on Mospheira.”

“No. No mecheiti.”

“You hunt.”

“Sometimes.”

“On Mospheira?”

Were they talking about guns, now? Was that where this was going? “I have. A few times. Small game. Very small.”

“One remembers,” Cenedi said—as if any living atevi couldremember. “Is it very different, Mospheira?”

“From Malguri?” One didn’t quite go off one’s guard. “Very. From Shejidan—much less so.”

“It was reputed—quite beautiful before the War.”

“It still is. We have very strict rules—protection of the rivers, the scenic areas. Preservation of the species we found there.”

Cenedi leaned back in his chair. “Do you think, nadi, there’ll be a time Mospheira will open up—to either side of the strait?”

“I hope it will happen.”

“But do you think it willhappen, nand’ paidhi?”

Cenedi might have gotten to his subject, or might have led away from the matter of the gun simply to make him relax. He couldn’t figure—and he felt more than a mild unease. The question touched policy matters on which he couldn’t comment without consultation. He didn’t want to say no to Cenedi, when Cenedi was being pleasant. It could target whole new areas for Cenedi’s curiosity. “It’s my hope. That’s all I can say.” He took a sip of hot tea. “It’s what I work very hard for, someday to have that happen, but no paidhi can say when—it’s for aijiin and presidenti to work out.”

“Do you think this television interview is—what is your expression?—a step in the right direction?”

Is thatit? Publicity? Tabini’s campaign for association with Mospheira? “Honestly, nadi Cenedi, I was disappointed. I don’t think we got to any depth. There are things I wanted to say. And they never asked me those. I wasn’t sure what they wanted to do with it. It worried me—what they might put in, that I hadn’t meant.”

“I understand there’s some thought about monthly broadcasts. The paidhi to the masses.”

“I don’t know. I certainly don’t decide things like that on my own. I’m obliged to consult.”

“By human laws, you mean.”

“Yes.”

“You’re not autonomous.”

“No. I’m not.” Early on, atevi had expected paidhiin to make and keep agreements—but the court in Shejidan didn’t have this misconception now, and he didn’t believe Cenedi was any less informed. “Though in practicality, nadi, paidhiin aren’t often overruled. We just don’t promise what we don’t think our council will accept. Though we do argue with our council, and sometimes we win.”

“Do you favor more interviews? Will you argue for the idea?”

Ilisidi was on the conservative side of her years. Probably she didn’t like television cameras in Malguri, let alone the idea of the paidhi on regular network broadcasts. He could imagine what she might say to Tabini.

“I don’t know what position I’ll argue. Maybe I’ll wait and see how atevi like the first one. Whether people wantto see a human face—or not. I may frighten the children.”

Cenedi laughed. “Your face has already been on television, nand’ paidhi, at least the official clips. ‘The paidhi discussed the highway program with the minister of Works, the paidhi has indicated a major new release forthcoming in microelectronics…’ ”

“But that’s not an interview. And a still picture. I can’t understand why anyone would want to hear me discuss the relative merits of microcircuits for an hour-long program.”

“Ah, but your microcircuits work by numbers. Such intricate geometries. The hobbyists would deluge the phone system. ‘Give us the paidhi,’ they’d say. ‘Let us hear the numbers.’ ”

He wasn’t sure Cenedi was joking at first. A few days removed from the Bu-javid and one could forget the intensity, the passion of the devout number-counters. He decided it wasa joke—Tabini’s sort of joke, irreverent of the believers, impatient of the complications their factions created.

“Or people can think my proposals contain wicked numbers,” Bren said, himself taking a more serious turn. “As evidently some do think.” And a second diversion, Cenedi delaying to reveal his reasons. “– Isit a blown fuse, this time, nadi?”

“I think it’s a short somewhere. The breaker keeps going off. They’re trying to find the source.”

“Jago received some message from Banichi a while ago that distressed her, and she left. It worried me, nadi. So did your summons. Do you have any idea what’s going on?”

“Banichi’s working with the house maintenance staff. I don’t know what he might have found, but he’s extremely exacting. His subordinates do hurry when they’re asked.” Cenedi took another drink of tea, a large one, and set the cup down. “I wouldn’t worry about it. He’d have advised me, I think, if he’d found anything irregular. Certainly house maintenance would, independent of him.—Another cup, nadi?”

He’d diverted Cenedi from his conversation. He was obligated to another cup. “Thank you,” he said, and started to get up to get his own tea, in the absence of a servant, and not suggesting Cenedi do the office, but Cenedi signaled otherwise, reached a long arm across the corner of the desk, picked up the pot and poured for him and for himself.

“Nadi, a personal curiosity—and I’ve never had the paidhi at hand to ask: all these years you’ve been dealing out secrets. When will you be out of them? And what will you do then?”

Odd that no one had ever asked the paidhiin that quite that plainly… on thisside of the water, although God knew they agonized over it on Mospheira.

And perhaps that wasCenedi’s own and personal question, though not thequestion, he was sure, which Cenedi had called him downstairs specifically to answer. It was the sort of thing an astute news service might ask. The sort of thing a child might… not a political sophisticate like Cenedi, not officially.

But it was very much the sort of question he’d already begun to hint at in technical meetings, testing the waters, beginning, one hoped, to shift attitudes among atevi, and knowing atevi couldn’t go much farther down certain paths without developments resisted for years by vested interests in other departments.

“Things don’t only flow one way across the strait, nadi. We learn from yourscientists, quite often. Not to say we’ve stood still ourselves since the Landing. But the essential principles have been on the table for a hundred years. I’m not a scientist—but as I understand it, it’s the intervening steps, the things that atevi science has to do before the principles in other areas become clear—those are the things still missing. There’s materials science. There’s the kind of industry it takes to support the science. And the education necessary for new generations to understand it. The councils are still debating the shape of baffles in fuel tanks—when no one’s teaching the students in the schools whyyou need a slosh baffle in the first place.”

“You find us slow students?”

Thattrap was obvious as a pit in the floor. And damned right they’d expected atevi to pick things up faster—give or take aijiin who wouldn’t budge and committees that wouldn’t release a process until they’d debated it to death. An incredibly short path to flight and advanced metallurgy. An incredibly difficult one to get a damn bridge built as it needed to be to stand the stresses of heavy-hauling trains.

“Extremely quick students,” he said, “interminable debaters.”

Cenedi laughed. “And humans debate nothing.”

“But we don’t have to debate the technology, nadi Cenedi. We haveit. We useit.”

“Did it bring you success?”

Watch it, he thought. Watchit. He gave a self-deprecating shrug, atevi-style. “We’re comfortable in the association we’ve made. The last secrets arepotentially on the table, nadi. We just can’t get atevi conservatives to accept the essential parts of them. Our secrets are full of numbers. Our numbers describe the universe. And how can the universe be unfortunate? We are confused when certain people claim the numbers add in anything but felicitous combination. We can only believe nature.” He was talking to Ilisidi’sseniormost guard, Ilisidi, who chose to reside in Malguri. Ilisidi, who hunted for her table—but believed in the necessity of dragonettes. “Surely, in my own opinion, not an expert opinion, nadi, someone must have added in what nature didn’t put in the equations.”

It was a very reckless thing to say, on one level. On the other, he hadn’t said whichphilosophy of numbers he faulted and which he favored, out of half a dozen he personally knew in practice, and, human-wise, couldn’tdo in his head. He personally wanted to know where Cenedi, personally, stood—and Cenedi’s mouth tightened in a rare amusement.

“While the computers you design secretly assign unlucky attributes,” Cenedi said wryly. “And swing the stars in their courses.”

“Not that I’ve seen happen. The stars go where nature has them going, nadi Cenedi. The same with the reasons for slosh baffles.”

“Are we superstitious fools?”

“Assuredly not. There’s nothing wrongwith this world. There’s nothing wrong with Malguri. There’s nothing wrongwith the way things worked before we arrived. It’s just—if atevi want what we know—”

“Counting numbers is folly?”

Cenedi wanted him to admit to heresy. He had a sudden, panicked fear of a hidden tape recorder—and an equal fear of a lie to this man, a lie that would break the pretense of courtesy with Cenedi before he completely understood what the game was.

“We’ve given atevi true numbers, nadi, I’ll swear to that. Numbers that work, although some doubt them, even in the face of the evidence of nature right in front of them.”

“Some doubt human good will, more than they doubt the numbers.”

So it wasn’tcasual conversation Cenedi was making. They sat here by the light of oil lamps– hesat here, in Cenedi’s territory, with his own security elsewhere and, for all he knew, uninformed of his position, his conversation, his danger.

“Nadi, my predecessors in the office never made any secret how we came here. We arrived at this star completely by accident, and completely desperate. We’d no idea atevi existed. We didn’t want to starve to death. We saw our equipment damaged. We knew it was a risk to us and, I admit it, to you, for us to go down from the station and land—but we saw atevi already well advanced down a technological path very similar to ours. We thoughtwe could avoid harming anyone. We thoughtthe place where we landed was remote from any association—since it had no buildings. That was the first mistake.”

“Which party do you consider made the second?”

They were charting a course through ice floes. Nothing Cenedi asked was forbidden. Nothing he answered was controversial—right down the line of the accepted truth as paidhiin had told it for over a hundred years.

But he thought for a fleeting second about the mecheiti, and about atevi government, while Cenedi waited—too long, he thought, to let him refuse the man some gain.

“I blame the War,” he said, “on both sides giving wrong signals. We thought we’d received encouragement to things that turned out quite wrong, fatally wrong, as it turned out.”

“What sort of encouragement?”

“We thought we’d received encouragement to come close, encouragement to treat each other as…” There wasn’t a word. “Known. After we’d developed expectations. We went to all-out war afterwe’d had a promising beginning of a settlement. People who think they were betrayed don’t believe twice in assurances.”

“You’re saying you weren’t at fault.”

“I’m saying atevi weren’t, either. I believe that.”

Cenedi tapped the fingers of one hand, together, against the desk, thinking, it seemed. Then: “An accident brought you to us. Was it a mistake of numbers?”

He found breath scarce in the room, perhaps the oil lamps, perhaps having gone in over his head with a very well-prepared man.

“We don’t know,” he said. “Or I don’t. I’m not a scientist.”

“But don’t your numbers describe nature? Was it a supernatural accident?”

“I don’t think so, nadi. Machinery may have broken. Such things do happen. Space is a vacuum, but it has dust, it has rocks—like trying to figure which of millions of dust motes you might disturb by breathing.”

“Then your numbers aren’t perfect.”

Another pitfall of heresy. “Nadi, engineers approximate, and nature corrects them. We approachnature. Our numbers work, and nature doesn’t correct us constantly. Only sometimes. We’re good. We’re not perfect.”

“And the War was one of these imperfections?”

“A very great one.—But we can learn, nadi. I’ve insulted Jago at least twice, but she was patient until I figured it out. Banichi’s made me extremely unhappy—and I know for certain he didn’t know what he did, but I don’t cease to value associating with him. I’ve probably done harm to others I don’t know about,—but at least, at least, nadi, at very least we’re not angry with each other, and we each knowthat the other side means to be fair. We make a lot of mistakes… but people can make up their minds to be patient.”

Cenedi sat staring at him, giving him the feeling… he didn’t know why… that he had entered on very shaky ground with Cenedi. But he hadn’t lost yet. He hadn’t made a fatal mistake. He wished he knew whether Banichi knew where he was at the moment.

“Yet,” Cenedi said, “someone wasn’t patient. Someone attempted your life.”

“Evidently.”

“Do you have any idea why?”

“I have noidea, nadi. I truly don’t, in specific, but I’m aware some people just don’t like humans.”

Cenedi opened the drawer of his desk and took out a roll of paper heavy with the red and black ribbons of the aiji’s house.

Ilisidi’s, he thought apprehensively, as Cenedi passed it across the desk to him. He unrolled it and saw instead a familiar hand.

Tabini’s.

I send you a man, ’Sidi-ji, for your disposition. I have filed Intent on his behalf, for his protection from faceless agencies, not, I think, agencies faceless to you, but I make no complaint against you regarding a course of action which under extraordinary circumstances you personally may have considered necessary.

What is this? he thought and, in the sudden, frantic sense of limited time, read again, trying to understand was it Tabini’s threat againstIlisidi or was he saying Ilisidi was behindthe attack on him?

And Tabini sent him here?

Therefore I relieve you of that unpleasant and dangerous necessity, ’Sidi-ji, my favorite enemy, knowing that others may have acted against me invidiously, or for personal gain, but that you, alone, have consistently taken a stand of principle and policy against the Treaty.

Neither I nor my agents will oppose your inquiries or your disposition of the paidhi-aiji at this most dangerous juncture. I require only that you inform me of your considered conclusions, and we will discuss solutions and choices.

Disposition of the paidhi? Tabini, Tabini, for God’s sake, what are you doingto me?

My agents have instructions to remain but not to interfere.

Tabini-aiji with profound respect

To Ilisidi of Malguri, in Malguri, in Maidingi Province…

His hands shook. He tried not to let them. He read the letter two and three times, and found no other possible interpretation. It wasTabini’s handwriting. It wasTabini’s seal. There was no possible forgery. He tried to memorize the wording in the little time he reasonably had to hold the document, but the elaborate letters blurred in his eyes. Reason tried to intervene, interposing the professional, intellectual understanding that Tabini wasatevi, that friendship didn’t guide him, that Tabini couldn’t even comprehend the word.

That Tabini, in the long run, had to act in atevi interests, and as an ateva, not in any human-influenced way that needed to make sense to him.

Intellect argued that he couldn’t waste time feeling anything, or interpreting anything by human rules. Intellect argued that he was in dire and deep trouble in this place, that he had a slim hope in the indication that Banichi and Jago were to stay here—an even wilder hope in the possibility Tabini might have been compelled to betray him, and that Tabini had kept Banichi and Jago on hand for a reason… a wild and improbable rescue…

But it was all a very thin, very remote possibility, considering that Tabini had felt constrained to write such a letter at all.

And if Tabini was willing to risk the paidhi’s life and along with it the advantage of Mospheira’s technology, one could only conclude that Tabini’s power was threatened in some substantial way that Tabini couldn’t resist.

Or one could argue that the paidhi had completely failed to understand the situation he was in.

Which offered no hope, either.

He handed Cenedi back the letter with, he hoped, not quite so obvious a tremor in his hands as might have been. He wasn’t afraid. He found that curious. He was aware only of a knot in his throat, and a chill lack of sensation in his fingers.

“Nadi,” he said quietly. “I don’t understand. Are you the ones trying to kill me in Shejidan?”

“Not directly. But denial wouldn’t serve the truth, either.”

Tabini had armed him contrary to the treaty.

Cenedi had killedan assassin on the grounds. Hadn’t he?

The confusion piled up around him.

“Where’s Banichi? And Jago? Do they know about this? Do they know where I am?”

“They know. I say that denial of responsibility would be a lie. But I will also own that we are embarrassed by the actions of an associate who called on a licensed professional for a disgraceful action. The Guild has been embarrassed by the actions of a single individual acting for personal conviction. I personally—embarrassed myself, in the incident of the tea. More, you accepted my apology, which makes my duty at this moment no easier, nand’ paidhi. I assure you there is nothingpersonal in this confrontation. But I will do whatever I feel sufficient to find the truth in this situation.”

“What situation?”

“Nand’ paidhi. Do you ever mislead us? Do you ever tell us less—or more—than the truth?”

His hazard didn’t warrant rushing to judgment headlong—or dealing in on-the-spot absolutes, with a man the extent of whose information or misinformation he didn’t know. He tried to think. He tried to be absolutely careful.

“Nadi, there are times I may know… some small technical detail, a circuit, a mode of operation—sometimes a whole technological field—that I haven’t brought to the appropriate committee; or that I haven’t put forward to the aiji. But it’s not that I don’t intend to bring it forward, no more than other paidhiin have ever withheld what they know. There is no technology we have that I intendto withhold—ever.”

“Have you ever, in collaboration with Tabini, rendered additional numbers into the transmissions from Mospheira to the station?”

God.

“Ask the aiji.”

“Have those numbers been supplied to you by the aiji?”

“Ask him.”

Cenedi looked through papers, and looked up again, his dark face absolutely impassive. “I’m asking you, nand’ paidhi. Have those numbers been supplied to you by the aiji?”

“That’s Tabini’s business. Not mine.” His hands were cold. He worked his fingers and tried to pretend to himself that the debate was no more serious than a council meeting, at which, very rarely, the questions grew hot and quick. “If Tabini-aiji sends to Mospheira, I render what he says accurately. That’s my job. I wouldn’t misrepresent him, or Mospheira. Thatis my integrity, nadi Cenedi. I don’t lie to either party.”

Another silence, long and tense, in which the thunder of an outside storm rumbled through the stones.

“Have you always told the truth, nadi?”

“In such transactions? Yes. To both sides.”

“ Ihave questions for you, in the name of the aiji-dowager. Will you answer them?”

The walls of the trap closed. It was the nightmare every paidhi had feared and no one had yet met, until, God help him, he had walked right into it, trusting atevi even though he couldn’t translate the concept of trust to them, persisting in trusting them when his own advisors said no, standing so doggedly by his belief in Tabini’s personal attachment to him that he hadn’tcalled his office when he’d received every possible warning things were going wrong.

If Cenedi wanted to use force now… he had no help. If Cenedi wanted him to swear that there wasa human plot against atevi… he had no idea whether he could hold out against saying whatever Cenedi wanted.

He gave a slight, atevi shrug, a move of one hand. “As best I can,” he said, ‘I’ll answer, as best I personally know the answers.”

“Mospheira has… how many people?”

“About four million.”

“No atevi.”

“No atevi.”

“Have atevi ever come there, since the Treaty?”

“No, nadi. There haven’t. Except the airline crews.”

“What do you think of the concept of a paidhi-atevi?”

“Early on, we wanted it. We tried to get it into the Treaty as a condition of the cease fire, because we wanted to understand atevi better than we did. We knew we’d misunderstood. We knew we were partially responsible for the War. But atevi refused. If atevi were willing, now, absolutely I’d support the idea.”

“You’ve nothing to hide, you as a people? It wouldn’t provoke resentment, to have an ateva resident on Mospheira, admitted to your councils?”

“I think it would be very useful for atevi to learn our customs. I’d sponsor it. I’d argue passionately in favor of it.”

“You don’t fear atevi spies any longer.”

“I’ve told you—there are no more secrets. There’s nothing to spy on. We live very similar lives. We have very similar conveniences. You wouldn’t know the difference between Adams Town and Shejidan.”

“I would not?”

“We’re very similar. And not—” he added deliberately, “not that all the influence has come from us to you, nadi. I tell you, we’ve found a good many atevi ideas very wise. You’d feel quite at home in some particulars. We have learned from you.”

He doubted Cenedi quite believed that. He saw the frown.

“Could there,” Cenedi asked him, “regarding the secrets you say you’ve provided—be any important area held back?”

“Biological research. Understanding of genetics. That’s the last, the most difficult.”

“Why is that the last?”

“Numbers. Like space. The size of the numbers. One hopes that computers will find more general acceptance among atevi. One needscomputers, nadi, adept as you are in mathematics—you still need them. I confess I can’t follow everything you do in your heads, but you have to have the computers for space science, for record-keeping, and for genetics as we practice it.”

“The number-counters don’t believe that. Some say computers are inauspicious and misleading.”

“Some also do admit a fascination with them. I’ve heard some numerologists are writing software… and criticizing our hardware. They’re quite right. Our scientists are very interested in their opinions.”

“In atevi invention.”

“Very much so.”

“What can we possibly invent? Humans have done it all.”

“Oh, no, no, nadi, far from all. It’s a wide universe. And our ship did once break down.”

“Wide enough, this universe?”

He almost said—beyond calculation. But that was heresy. “At least beyond what I know, nadi. Beyond any limit we’ve found with our ships.”