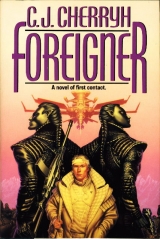

Текст книги "Foreigner"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

He cast about for what to do with himself, and thought about a resumption of his regular habits, watching the evening news… which, now that he thought about it, he had no television to receive.

He didn’t ask the servants about the matter. He opened cabinets and armoires, and finally made the entire circuit of the apartments, looking for nothing more basic now than a power tap.

Not one. Not a hint of accommodation for television or telephones.

Or computer recharges.

He thought about ringing the bell, rousing the servants and demanding an extension cord, at least, so he could use his almost depleted computer tonight, if they had to run the cord up from the kitchens or via an adapter, which had to exist in some electronics store in this benighted district, down from an electric light socket.

But Banichi hadn’t put in an appearance since they parted company downstairs, Jago had refused the request for a phone already, and after pacing the carpeted wooden floors awhile and investigating the small library for something to do, he went to bed in disgust—flung himself into the curtained bed among the skins of dead animals and discovered that one, there was no reading light, two, the lights were all controlled from a switch at the doorway; and, three, a dead and angry beast was staring straight at him, from the opposite wall.

It wasn’t me, he thought at it. It wasn’t my fault. I probably wasn’t born when you died.

My species probably hadn’t left the homeworld yet.

It’s not my fault, beast. We’re both stuck here.

IV

« ^ »

Morning dawned through a rain-spattered glass, and breakfast didn’t arrive automatically. He pulled the chain to call for it, delivered his request to Maigi, who was at least prompt to appear, and had Djinana light the fire for an after-breakfast bath.

Then there was the “accommodation” question; and, faced with trekking downstairs before breakfast in search of a modern bathroom, he opted for privacy and for coping with what evidently worked, in its fashion, which required no embarrassed questions and no (diplomatically speaking) appearance of despising what was—with effort—an elegant, historic hospitality. He managed. He decided that, left alone, he could get used to it.

The paidhi’s job, he thought, was to adapt. Somehow.

Breakfast, God, was four courses. He saw his waistline doubling before his eyes and ordered a simple poached fish and piece of fruit for lunch, then shooed the servants out and took his leisurely bath, thoroughly self-indulgent. Life in Malguri was of necessity a matter of planning ahead, not just turning a tap. But the water was hot.

He didn’t ask Tano and Algini in for their non-conversation while he bathed (“Yes, nadi, no, nadi.”) or their help in dressing. He found no actual purpose for dressing: no agenda, nowhere to go until lunch, so far as Banichi and Jago had advised him.

So he wrapped himself in his dressing gown and stared out the study window at a grayness in which the blue and amber glass edging was the only color. The lake was silver gray, set in dark gray bluffs and fog. The sky was milky gray, portending more rain. A last few drops jeweled the glass.

It was exotic. It damned sure wasn’t Shejidan. It wasn’t Mospheira, it wasn’t human, and it wasn’t so far as he could see any safer than Tabini’s own household, just less convenient. Without a plug-in for his computer.

Maybe the assassin wouldn’t spend a plane ticket on him.

Maybe boredom would send the rascal back to livelier climes.

Maybe after a week of this splendid luxury he would hike to the train station and join the assassin in an escape himself.

Fancies, all.

He took the guest book from its shelf—anything to occupy his mind—took it back to the window where there was better light and leafed through it, looking at the names, realizing—as the leaves were added forward, rather than the reverse, after the habit of atevi books—that he was holding an antiquity that went back seven hundred years, at least; and that most of the occupants of these rooms had been aijiin, or the in-laws of aijiin, some of them well-known in history, like Pagioni, like Dagina, who’d signed the Controlled Resources Development Treaty with Mospheira—a canny, hard-headed fellow, who, thank God, had knocked heads together and eliminated a few highly dangerous, warlike obstacles in ways humans couldn’t.

He was truly impressed. He opened it from the back, as atevi read—the right-left direction, and down—and discovered the foundation date of the first fortress on the site, as the van driver had said, was indeed an incredible two thousand years ago. Built of native stone, to hold the valuable water resource of Maidingi for the lowlands, and to prevent the constant raiding of hill tribes on the villages of the plain. The second, expanded, fortress—one supposed, including these very walls—dated from the sixty-first century.

He leafed through changes and additions, found a tour schedule, of all things, once monthly, confined to the lower hall– (We ask our guests to ignore this monthly visit, which the aiji feels necessary and proper, as Malguri represents a treasure belonging to the people of the provinces. Should a guest wish to receive tour groups in formal or informal audience, please inform the staff and they will be most happy to make all arrangements. Certain guests have indeed done so, to the delight and honor of the visitors…)

Shock hell out of them, I would, Bren thought glumly. Send children screaming for their parents. None of the people here have seen a human face-to-face.

Too much television, Banichi would say. Children in Shejidan had to be reassured about Mospheira, that humans weren’t going to leave there and turn up in their houses at night—so the report went. Atevi children knew about assassins. From television they knew about the War of the Landing. And the space station the world hadn’t asked to have. Which was going to swoop down and destroy the earth.

His predecessor twice removed had tried to arrange to let humans tour the outlying towns. Several mayors had backed the idea. One had died for it.

Paranoia still might run that deep—in the outlying districts—and he had no wish to push it, not now, not at this critical juncture, with one attempt already on his life. Lie low and lie quiet, was the role Tabini had assigned him, in sending him here. And he still, dammit, didn’t know what else he could have done wiser than he had, once the opportunity had passed to have made a phone call to Mospheira.

If there’d ever been such an opportunity.

Human pilots, in alternation with atevi crews, flew cargo from Mospheira to Shejidan, and to several coastal towns and back again… that was the freedom humans had now, when their forebears had flown between stars none of them remembered.

Now the paidhi would be arrested, most likely, if he took a walk to town after an extension cord. His appearance could start riots, economic panics, rumors of descending space stations and death rays.

He was depressed, to tell the truth. He had thought he had a good rapport with Tabini, he had thought, in his human way of needing such things, that Tabini was as close to a friend as an ateva was capable of being.

Something was damned well wrong. At least wrong enough that Tabini couldn’t confide it to him. That was what everything added up to—either officially or personally. And he put the codex back on the shelf and took to pacing the floor, not that he intended to, but he found himself doing it, back and forth, back and forth, to the bedroom and back, and out to the sitting room, where the view of the lake at least afforded a ray of sunlight through the clouds. It struck brilliant silver on the water.

It was a beautiful lake. It was a glorious view, when it wasn’t gray.

He could be inspired, if his breakfast wasn’t lying like lead on his stomach.

Hell if he wanted to go on being patient. The paidhi’s job might demand it. The paidhi’s job might be to sit still and figure out how to keep the peace, and maybe he hadn’t done that very well by discharging firearms in the aiji’s household. But…

He hadn’t looked for the gun. He hadn’t even thought about it. Tano and Algini and Jago had done the actual packing and unpacking of his belongings.

He blazed a straight course back to the bedroom, got down on his knees and felt under the mattress.

His fingers met hard metal. Two pieces of hard metal, one a gun and one a clip of shells.

He pulled them out, sitting on the floor as he was, in his dressing robe, with the gun in his hands and a sudden dread of someone walking in on him. He shoved the gun and the clip back where they belonged, and sat there asking himself—what in hell is this about?

Nothing but that the paidhi’s in cold storage. And armed. And guarded. And his guards won’t tell him a cursed thing.

Well, damn, he thought.

And gathered himself up off the floor in a sudden fit of resolution, intending to push it as far as he had latitude and find out where the boundaries (however nebulous) might be. He went to the armoire and pulled out a good pair of pants; a sweater, obstinately human and impossible for atevi to judge for status statements; and his good brown hunting boots, that being the style of this country house.

His favorite casual coat, the leather one.

Then he walked out the impressive front doors of his suite and down the hall, an easy, idle stroll, down the stairs to the stone-floored main floor, making no attempt whatsoever at stealth, and along the hall to the grand central room, where a fire burned wastefully in the hearth, where the lights were all candles, and the massive front doors were shut.

He walked about, idly examined the bric-a-brac, and objects on tables that might be functional and might be purely decorative—he didn’t know. He didn’t know what to call a good many of the objects on the walls, particularly the lethal ones. He didn’t recognize the odder heads and hides—he determined to find out the species and the status of those species, and add them to the data files for Mospheira, with illustrations, if he could get a book… or a copy machine…

… or plug in the computer.

His frustration hit new levels, at the latter thoughts. He thought about trying the front doors to see if they were locked, taking a walk out in the front courtyard, if they weren’t—maybe having a close up look at the cannon, and maybe at the gates and the road.

Then he decided that that was probably pushing Banichi’s good humor much too far; possibly, too, and more to the point, risking Banichi’s carefully laid security arrangements… which might catch him instead of an assassin.

So he opted to take a stroll back into the rest of the building instead, down an ornate corridor, and into plain ones, past doors he didn’t venture to open. If assassins might venture in here looking for him, especially in the dark, he wanted a mental map of the halls and the rooms and the stairways that might become escape routes.

He located the kitchens. And the storerooms.

And a hall at a right angle, which offered slit windows and a view out toward the mountains. He took that turn, having discovered, he supposed, the outside wall, and he walked the long corridor to the end, where he found a choice: one hallway tending off to the left and another to the right.

The left must be another wing of the building, he decided, and, seeing double doors down that direction, and those doors shut, he had a sudden chilling thought of personal residence areas, wires, and security systems.

He reasoned then that the more prudent direction for him to take, if he had come to private apartments of some sort, where security arrangements might be far more modern than the lighting, was back toward the front of the building, boxing the square toward the front hall and the foyer.

The hall he walked was going that direction, at about the right distance of separation, he was increasingly confident, to end up as the corridor that exited near the stairs leading up to his floor. He walked past one more side hall and a left-right-straight-ahead choice, and, indeed, ended in the archway entry to the grand hall in front of the lain doors, where the fireplace was.

Fairly good navigation, he thought, and walked back to the warmth of the fireplace, where he had started his exploration of the back halls.

“Well,” someone said, close behind him.

He had thought the fireside unoccupied. He turned in alarm to see a wizened little ateva, with white in her black hair, sitting in one of the high-backed leather chairs… diminutive woman—for her kind.

“Well?” she said again, and snapped her book closed. “You’re Bren. Yes?”

“You’re…” He struggled with titles and politics—different honorifics, when one was face to face with an atevi lord. “The esteemed aiji-dowager.”

“Esteemed, hell. Tell that to the hasdrawad.” She beckoned with a thin, wrinkled hand. “Come here.”

He moved without even thinking to move. That was the command in Ilisidi. Her finger indicated the spot in front of her chair, and he moved there and stood while she looked him up and down, with pale yellow eyes that had to be a family trait. They made the recipient of that stare think of everything he’d done in the last thirty hours.

“Puny sort,” she said.

People didn’t cross the dowager. That was well reputed.

“Not for my species, nand’ dowager.”

“Machines to open doors. Machines to climb stairs. Small wonder.”

“Machines to fly. Machines to fly between stars.” Maybe she reminded him of Tabini. He was suddenly over the edge of courtesy between strangers. He had forgotten the honorifics and argued with her. He found no way back from his position. Tabini would never respect a retreat. Neither would Ilisidi, he was convinced of that in the instant he saw the tightening of the jaw, the spark of fire in the eyes that were Tabini’s own.

“And you let us have what suits our backward selves.”

Gave him back the direct retort, indeed. He bowed.

“I recall you won the War, nand’ dowager.”

“ Didwe?”

Those yellow, pale eyes were quick, the wrinkles around her mouth all said decisiveness. She shot at him. He shot back,

“Tabini-aiji also says it’s questionable. We argue.”

“Sit down!”

It was progress, of a kind. He bowed, and drew up the convenient footstool rather than fuss with a chair, which he didn’t think would further his case with the old lady.

“I’m dying,” Ilisidi snapped. “Do you know that?”

“Everyone is dying, nand’ dowager. I know that.”

Yellow eyes still held his, cruel and cold, and the aiji-dowager’s mouth drew down at the corners. “Impudent whelp.”

“Respectful, nand’ dowager, of one who hassurvived.”

The flesh at the corner of the eyes crinkled. The chin lifted, stern and square. “Cheap philosophy.”

“Not for your enemies, nand’ dowager.”

“How ismy grandson’s health?”

Almost she shook him. Almost. “As well as it deserves to be, nand’ dowager.”

“How well does it deserve to be?” She seized the cane beside her chair in a knobby hand and banged the ferule against the floor, once, twice, three times. “Damn you!” she shouted at no one in particular. “ Where’s the tea?”

The conversation was over, evidently. He was glad to find it was her servants who had trespassed her good will. “I’m sorry to have bothered you,” he began to say, and began to get up.

The cane hammered the stones. She swung her scowl on him. “Sit down!”

“I beg the dowager’s pardon, I—” Have a pressing engagement, he wanted to say, but he didn’t. In this place the lie was impossible.

Bang! went the cane. Bang! “Damnable layabouts! Cenedi! The tea!”

Was she sane? he asked himself. He sat. He didn’t know what else he could do, but sit. He wasn’t even sure there were servants, or that tea had been in the equation until it crossed her mind, but he supposed the aiji-dowager’s personal staff knew what to do with her.

Old staffers, Jago had said. Dangerous, Banichi had hinted.

Bang! Bang! “Cenedi! Do you hear me?”

Cenedi might be twenty years dead for all he knew. He sat frozen like a child on a footstool, arms about his knees, ready to defend his head and shoulders if Ilisidi’s whim turned the cane on him.

But to his relief, someone did show up, an atevi servant he took at first glance for Banichi, but it clearly wasn’t, on the second look. The same black uniform. But the face was lined with time and the hair was streaked liberally with gray,

“Two cups,” Ilisidi snapped.

“Easily, nand’ dowager,” the servant said.

Cenedi, Bren supposed, and he didn’t want tea, he had had his breakfast, all four courses of it. He was anxious to escape Ilisidi’s company and her hostile questions before he said or did something to cause trouble for Banichi, wherever Banichi was.

Or for Tabini.

If Tabini’s grandmother was, as she claimed, dying… she was possibly out of reasons to be patient with the world, which in Ilisidi’s declared opinion, had not done wisely to pass over her. This could be a dangerous and angry woman.

But a tea service regularly had six cups, and Cenedi set one filled cup in the dowager’s hand, and offered another to him, a cup which clearly he was to drink, and for a moment he could hear what wise atevi adults told every toddling child, don’t take, don’t touch, don’t talk with strangers—

Ilisidi took a delicate sip, and her implacable stare was on him. She was amused, he was sure. Perhaps she thought him a fool that he didn’t set down the cup at once and run for Banichi’s advice, or that he’d gotten himself this far in over his head, arguing with a woman no few atevi feared, and not for her insanity.

He took the sip. He found no other choice but abject flight, and that wasn’t the course the paidhi ever had open to him. He stared Ilisidi in the eyes when he did drink, and when he didn’t feel any strangeness from the cup or the tea, he took a second sip.

A web of wrinkles tightened about Ilisidi’s eyelids as she drank. He couldn’t see her mouth behind her hand and the cup, and when she lowered that cup, the web had all relaxed, leaving only the unrealized map of her years and her intentions, a maze of lines in the firelit black gloss of her skin.

“So what vices does the paidhi have in his spare time? Gambling? Sex with the servants?”

“It’s the paidhi’s business to be circumspect.”

“And celibate?”

It wasn’t a polite question. Nor politely meant, he feared. “Mospheira is an easy flight away, nand’ dowager. When I have the time to go home, I do. The last time…” He didn’t feel invited to chatter. But he preferred it to Ilisidi’s interrogation. “… was the 28th Madara.”

“So.” Another sip of tea. A flick of long, thin fingers. “Doubtless a tale of perversions.”

“I paid respects to my mother and brother.”

“And your father?”

A more difficult question. “Estranged.”

“On an island?”

“The aiji-dowager may know, we don’t pursue blood-feud. Only law.”

“A cold-blooded lot.”

“Historically, we practiced feud.”

“Ah. And is this anotherthing your great wisdom found unwise?”

He sensed, perhaps, the core of her resentments. He wasn’t sure. But he had trod that minefield before—it was known territory, and he looked her straight in the face. “The paidhi’s job is to advise. If the aiji rejects our advice…”

“You wait,” she finished for him, “for another aiji, another paidhi. But you expect to get your way.”

No one had ever put it so bluntly to him. He had wondered if the atevi did understand, though he had thought they had.

“Situations change, nand’ dowager.”

“Your tea’s getting cold.” He sipped it. It was indeed cold, quickly chilled, in the small cups. He wondered if she knew what had brought him to Malguri. He had had the image of an old woman out of touch with the world, and now he thought not. He emptied the cup.

Ilisidi emptied hers, and flung it at the fire. Porcelain shattered. He jumped—shaken by the violence, asking himself again if Ilisidi was mad.

“I never favored that tea service,” Ilisidi said.

He had the momentary impulse to send his cup after it. If Tabini had said the like, Tabini would have been testing him, and he would have thrown it. But he didn’t know Ilisidi. He had to take that into account for good and all. He rose and handed his cup to Cenedi, who waited with the tray.

Cenedi hurled the whole set at the fireplace. Tea hissed in the coals. Porcelain lay shattered.

Bren bowed, as if he had received a compliment, and saw an old woman who, dying, sitting in the midst of this prized antiquity, destroyed what offended her preferences, broke what was ancient and priceless, because shedidn’t like it. He looked for escape, murmured, “I thank the aiji-dowager for her attention,” and got two steps away before bang! went the cane on the stones, and he stopped and faced back again, constrained by atevi custom—and the suspicion what service Cenedi was to her.

He had amused the aiji-dowager. She was grinning, laughing with a humor that shook her thin body, as she leaned both hands on the cane. “Run,” she said. “Run, nand’ paidhi. But where’s safe? Do you know?”

“This place,” he shot back. One didn’tretreat from direct challenges—not if one wasn’t a child, and wasn’t anyone’s servant. “Your residence. The aiji thought so.”

She didn’t say a thing, just grinned and laughed and rocked back and forth on the pivot of the cane. After an anxious moment he decided he was dismissed, and bowed, and headed away, hoping she was through with jokes, and asking himself was Ilisidi sane, or had Tabini known, or whyhad she destroyed the tea service?

Because a human had profaned it?

Or because there was something in the tea, that now was vapor on the winds above the chimney? His stomach was upset. He told himself it was suggestion. He reminded himself there were some teas humans shouldn’t drink.

His pulse was hammering as he walked the hall and climbed the stairs, and he wondered if he should try to throw up, or where, or if he could get to his own bathroom to do it… not to upset the staff… or lose his dignity…

Which was stupid, if he was poisoned. Possibly it was fear that was making his heart race. Possibly it was one of those stimulants like midarga, which in overdoses could put a human in the emergency room, and he should find Banichi or Jago and tell them what he’d done, and what he’d drunk, that was already making its way into his bloodstream.

A clammy sweat was on his skin as he reached the upper hall. It might be nothing more than fear, and suggestion, but he couldn’t get air enough, and there was a darkening around the edges of his vision. The hall became a nightmare, echoing with his steps on the wooden floor. He put out a hand to the wall to steady himself and his hand vanished into a strange dark nowhere at the side of his vision.

I’m in serious trouble, he thought. I have to get to the door. I mustn’t fall in the hallway. I mustn’t make it obvious I’m reacting to the stuff… never show fear, never show discomfort…

The door wobbled closer and larger in the midst of the dark tunnel. He had a blurred view of the latch, pushed down on it. The door opened and let him into the blinding glare of the windows, white as molten metal.

Close the door, he thought. Lock it. I’m going to bed. I might fall asleep awhile. Can’t sleep with the door unlocked.

The latch caught. He was sure of that. He faced the glare of the windows, staggered a few steps and then found he was going the wrong way, into the light.

“Nadi Bren!”

He swung around, frightened by the echoing sound, frightened by the darkness that loomed up on every side of him, around the edges and now in the center of his vision, darkness that reached out arms and caught him and swept him off his feet in a whirling of all his concept of up and down.

Then it was white, white, until the vision went gray again and violent, and he was bent over a stone edge, with someone shouting orders that echoed in his ears, and peeling his sweater off over his head.

Water blasted the back of his head, then, cold water, a battering flood that rattled his brain in his skull. He sucked in an involuntary, watery gasp of air, and tried to fight against drowning, but an iron grip held his arms and another—whoever it was had too many hands—gripped the back of his neck and kept him where he was. If he tried to turn his head, he choked. If he stayed where he was, head down to the torrent, he could breathe, between spasms of a gut that couldn’t get rid of any more than it had.

A pain stung his arm. Someone had stuck him and he was bleeding, or his arm was swelling, and whoever was holding him was still bent on drowning him. Waves of nausea rolled through his gut, he could feel the burning of tides in his blood that didn’t have anything to do with this world’s moons. They weren’t human, the things that surrounded him and constrained him, and they didn’t like him—even at best, atevi wished humanity had never been, never come here… there’d been so much blood, holding on to Mospheira, and they were guilty, but what else could they have done?

He began to chill. The cold of the water went deeper and deeper into his skull, until the dark began to go away, and he could see the gray stone, and the water in the tub, and feel the grip on his neck and his arms as painful. His knees hurt, on the stones. His arms were numb.

And his head began to feel light and strange. Is this dying? he wondered. Am I dying? Banichi’s going to be mad if that’s the case.

“Cut the water,” Banichi said, and of a sudden Bren found himself hauled over onto his back, dumped into what he vaguely decided was a lap, and felt a blanket, a very welcome but inadequate blanket, thrown over his chilled skin. Sight came and went. He thought it was a yellow blanket, he didn’t know why it mattered. He was scared as someone picked him up like a child and carried him, that that person was going to try to carry him down the stairs, which were somewhere about, the last he remembered. He didn’t feel at all secure, being carried.

The arms gave way and dumped him.

He yelled. His back and shoulders hit a mattress, and the rest of him followed.

Then someone rolled him roughly onto his face on silken, skidding furs, and pulled off his blanket, his boots and his trousers, while he just lay there, paralyzed, aware of all of it, but aware too of a pain in his temples that forecast a very bad headache. He heard Banichi’s voice out of the general murmur in the room, so it was all right now. It would be all right, since Banichi was here. He said, to help Banichi,

“I drank the tea.”

A blow exploded across his ear. “Fool!” Banichi said, from above him, and flung him over onto his back and covered him with furs.

It didn’t help the headache, which was rising at a rate that scared him and made his heart race. He thought of stroke, or aneurism, or an impending heart attack. Only where Banichi had hit his ear was hot and halfway numb. Banichi grabbed his arm and stuck him with a needle—it hurt, but not near the pain his head was beginning to have.

After that, he just wanted to lie there submerged in dead animal skins, and breathe. He listened to his own heartbeat, he timed his breaths, he found troughs between the waves of pain, and lived in those, while his eyes ran tears from the daylight and he wished he was sane enough to tell Banichi to draw the drapes.

“This isn’t Shejidan!” Banichi railed at him. “Things don’t come in plastic packages!”

He knew that. He wasn’t stupid. He remembered where he was, though he wasn’t sure what plastic packages had to do with anything. The headache reached a point he thought he was going to die and he wanted to have it over with—

But you didn’t say that to atevi, who didn’t think the same as humans, and Banichi was already mad at him.

Justifiably. This was the second time in a week Banichi had had to rescue him. He kept asking himself had the aiji-dowager tried to kill him, and tried to warn Banichi that Cenedi was an assassin—he was sure he was. He looked like Banichi—he wasn’t sure that was a compelling logic, but he tried to structure his arguments so Banichi wouldn’t think he was a total fool.

“Cenedi did this?”

He thought he’d said so. He wasn’t sure. His head hurt too much. He just wanted to lie there in the warm furs and go to sleep and not have it hurt when and if he woke up, but he was scared to let go, because he might never wake up and he hadn’t called Hanks.

Banichi crossed the room and talked to someone. He wasn’t sure, but he thought it was Jago. He hoped there wasn’t going to be trouble, and that they weren’t under attack of some kind. He wished he could follow what they were saying.

He shut his eyes. The light hurt them too much. Someone asked if he was all right, and he decided if he weren’t all right, Banichi would call doctors or something, so he nodded that he was, and slid off into the dark, thinking maybe he had called Hanks, or maybe just thought about calling Hanks. He wasn’t sure.