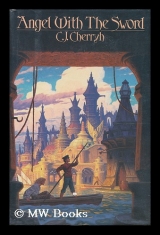

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

"You go on in with him, gran," Altair said. "He won't mind."

"I got a cap for 'im," Mintaka said, and bent down. "Son, c'n you feel about a bit and find a sack, she'll be right over to the starb'd—"

There was a bit of to-do. There were several sacks. Altair poled them out into starlight and sent the little skip scudding along at a fair rate; and Mintaka kept on at her chatter, hunting the proper sack.

"Gran," Mondragon said from inside, "come on in, I truly wish you would."

"Well," Mintaka said, and finally dithered her way inside. A nervous chuckle then, over the gentle whisper of the water. "Been a long time since I had a handsome fellow to myself in the hidey, you're such a nice boy. You got a wife?"

"No," Mondragon said in a small, definite voice. Altair gave the boat a cheerful shove.

That for you, Mondragon. Serves you right, got yourself cornered, have you? Old woman's not so old as that, is she, Mondragon?

"Here she be," came the old voice, "here she be—got all my yarns. Ogh, you do be wet, don't you? Here, here, here we be. Folk give me yarn scrap, sometime give me yarn to do up for 'em—I knit real fancy, me hands being stiff all the same—here, here, I wish I had a light, can't afford a light, 'cept my little cookstove. I do up sweaters, real fine sweaters, ain't no man wearing one of my sweaters going to catch sick, I make the stitches fine, I tell you, you ever want a good sweater, you give me the yarn, I do you a sweater better'n you get in hightown. Do you a scarf, do you nice warm socks…"

The skip glided under the starlight and Altair watched the canalside at every weaving step, this side and that. Barred windows and iron shutters showed on canal level; old brick and old board and old stone, and here and there one of Merovingen's feral cats, stopping to stare with fixed curiosity at the unusual sight of a solitary skip on a wide black canal.

Must be a good one, cat, that set-to down there. You can still see the glow. Lord, I bet a bridge caught. Probably cut 'er down quick, Lord, salvage to be had, even to the charcoal. If it don't spread.

"… I had me twenty, thirty lovers," Mintaka was saying to her prisoner. "Oh, I moved light in them days, I used ter wear a feather in me cap an' I used to work that skip with me ma and me pa—Min, pa used ter say—"

Altair looked back. It was black, empty water, dancing to city lights; a web of bridges above. Eerie solitude all about. Ahead, Midtown Bridge spanned the Grand, pilings abundant at either end and clear water to the middle where barge traffic came, a sheen of deep water there.

And beyond, down by Port outlet, a scattering of boats like shadows, reflecting nothing, on water-shine that reflected fire.

Lord. Is it on the Grand now? Those'll be boats after the city penny, them as got strong backs, keeping those fire-booms where they belong.

She kept up the pace, long since warmed, the feet long since numb.

Better to go barefoot, got no time to tend to it, don't hurt much now, anyhow.

She spared a hand to lift her cap and rake her hair with her fingers, settled it again. Took a sharp look to starboard where a small huddle of boats remained.

Old folk. Same as gran Mintaka. Same as Muggin.

The bow came into the open again, and Altair kept a steady pace, her hands swearing on the pole now as Port Canal outflow and the boats and the fire glare came closer and closer.

Questions, dammit, we don't need.

"… you buy that sweater uptown?" Mintaka was saying inside the tarp-shelter, with doubtless professional interest. "Lord, now they done used too big a needle, stuff stretches, them stitches got too much give. Now I could make ye one—"

Altair scanned the floating gathering ahead for the easiest course through, and suddenly thought wistful thoughts of taking the long way round, up the Foundry canal and up and around. It was a chancy backwater, old warehouses, an area where old Det was winning and buildings would have to be filled and torn down and built again. It had not happened yet.

Evade the questions, that was all. And oh, Lord, now there was Mintaka to reckon with.

Closer and closer, watching that fire-sheen and the drift of boats. She managed a steady pace, sweating now despite the chill of her clothing, breathing in great raw gasps.

It's all right, you're just Altair Jones, coming back with old gran Mintaka, doing a kindly act, just mind your own business—

She glided in amongst the first boats that anchored there, anchored, no less, right in the Grand channel. Families huddled on skip half decks, all wrapped in blankets, watching the commotion like it was holiday or a hanging. Intent on the fire and not on her, thank the Ancestors. Intent on the commotion of distant shouting round the bend where Port met Grand, where fire still showed, but dimmer now. Boats clustered there too, black and busy against the glare.

Mind your business, Jones, knock into someone and you'll have more than one question to answer, that you will.

There was a great deal of commotion now, noise from other boats as she worked and glided her way through. And the tarp stirred. "Lord, look at this," Mintaka's high voice said, and Altair cringed and kept poling.

"Ain't nothing, gran," she said. "You found that cap for him yet?"

"Oh, that I do." Mintaka hauled herself up and staggered perilously in the well, hunched, irregular silhouette against the fire-reflections and the passing shadows of boats. "Look at this, look at this—I tell you I ain't seen such a to-do since them two barges jammed up in the Grand. I tell you, they ought ter have a law, governor ought to do something, them damn bargefolk got no respect for nothing."

"They don't," Altair agreed.

Damn, the lonely old soul was a tale-teller. Chatter your brains away.

And come dawn gran Mintaka would have a good one, how Jones and a fair-haired uptowner showed up all wet and draggled and poled her back to safety. O Lord, Jones, now what do you do?

Scatter stories wide, that's all.

"I heard this barge run down a poleboater," she said. "There she was all blazing fire and come grinding up the bank there by Mars Bridge; and this poler, he jumped and his passenger did; and here was this uptown man swimming down the Port—did you know who that was, ser?"

"No," Mondragon said from beneath the tarp. "Myself —I had to jump when I ran afoul of a crew bringing a boom up. I hardly knew what hit me."

"I saw him go," Altair said cheerfully. "Right off the Mars walk, he went, damn fools rushing off to get to the fire. I got down and gave him a hand and this damn fool trod on me, never a care in the wide world. Stepped right on me leg. I tell you I'd like to've got up right men and settled with him, but it was bad enough this m'ser got shoved in, I couldn't leave off pulling him out. I asked him did he swallow any of that water, he said no. I just get my boat off old Del Suleiman and get to moving—"

The sight off the starboard distracted her: a welter of boats; watchers clustered there: and beyond that, fire-glare, a huge black hulk run up against a wall, something else ablaze in the river. One of the bridges was missing, thatwas what was burning in the river, and that black, dead hulk listing down onto the bottom—that was the barge they had been in.

A cold feeling hit her, belated shock. She glided a moment, recovered her wits and moved quickly to turn the bow from a potential scrape along another boat's anchor cable. She rocked them. Heads turned her way, silhouettes. The light was at their backs and on her.

"Oh, she were close,*' Mintaka said.

"Sorry, gran." She sweated and made a close turn amid the still boats and anchor-ropes.

We were onthat black thing. We were under that deck. Lord, if we'd been a second slower to get out of that hidey we'd have been trapped in there, that fuel running back in the slats under us—cinders and bits of bone. They never would've told us from the rest of the charcoal. Did everybody get offthat thing?

What kind of folk'd do a thing like that?

"Ain't no place t' anchor," Mintaka said. And shouted at the next boat: " Ain't no place t' anchor, hear?"

" Shut it down!" a voice yelled back, and voices yelled other things. " Who's that?"

" I'm Mintaka Fahd," the old woman yelled back, " and this here's Retribution working my boat, no thanks to you that left me!"

" She's crazy," someone else sang out. " Who is that?"

Altair gave a shove on the pole. ' ' It's Altair Jones,'' she yelled to the night at large, " taking this boat to dock, no thanks to them that ran off and left her! Who's seen Del Suleiman?"

A moment of relative silence and no answer. "You tell 'em," Mintaka said, and waddled forward. " You hear?"

"I think they did," Altair muttered. "Gran, your arthritis is going to do you bad, you better sit."

"I'm doing fine," Mintaka said, standing wide-legged in the bow. Probably she was not doing fine. Too cussed to agree.

And Del had not answered the hail.

The crowd of boats went right under Foundry Bridge, in the center as well as on the sides by the pilings. Altair went gingerly, fearing collision in that dark place; while Mintaka waddled back closer to the tarp.

"Almost there, gran," Altair said. "You want to sit a while?"

"Hey," Mintaka said; and Altair heard the silence too.

The great bell had stopped, proclaiming the emergency done.

"They got 'er," Altair said. Of course they had. Merovingen could not burn, her people were too canny and moved too quick, whatever the hood-wearing crazies did. Whatever she had gotten herself involved in.

She gave a shrug to rid herself of the chill it gave her, and shoved the boat on, past other moored boats, these with sense to clear the channel, boats tied up thick as birds at roost. Safer territory. The skip moved faster now, easy in the water on the outflow. Southtown Bridge loomed up, and the tall triple span of Fishmarket Bridge was the imagination of a shadow behind that.

"Oh," Mintaka said, standing by the tarp, "she do move, she do move. I used ter push her like this."

"She's a good boat," Altair said.

Mintaka said nothing then. Folded her arms up till she made a roundish lump in the dark.

Southtown bridge shadow went over them, narrowest span in the city. A body listened sharp for a barge bell here at night or early morning and got over right smartly if one sounded.

"Where you got in mind?" Mintaka asked. "Love, I ain't got no strength to fight Snake current."

"Well, I wouldn't leave you at the Southtown narrows, gran. I tell you, how's Ventani corner do you?"

"Oh, Ventani's fine, love. I tell you I don't know what I'd of done."

"Good thing I come along, that's what." Altair put her over to the side, where dozens of boats were moored, some few to each other thinning down as they came down to shallows where Ventani's rock stood firm, one of four upthrusts of stone in all of sinking Merovingen. "Hey," she said, spotting a vacancy. "There's one. Uptown canalers probably scared of the bottom, you got no problem light as she rides. Tide's already run." She gasped after breath, walking the skip in. "You want to tie her in, gran?"

They slid in next a number of skips—"How's she doing down there?" one man asked as they tied in, "They got that out?"

"They got 'er out," Mintaka said, walking to the side. And started filling in the details.

Lord. At it already.

Altair ran in the pole and got down on her knees on the halfdeck. Likely Mintaka collapsed and raised the tarp to get about, what times she moved at all. But there was no tie to the halfdeck and Altair slid down into the shelter, got head and shoulders under, into that closeness. It stank of old blankets and wet wool and mildew. "You awake?" she asked Mondragon,

"I assure you," he said in a voice all frosty cold. " Nowwhere?"

"Forward." She found him in the dark and gave him a push, reaching then to keep her cap on as she crawled out the curtain after him into the dark.

"—Jones here got me in," Mintaka was saying to the folk next over, and: "Lord, here's the nice uptown lad, ain't he fine? And Jones here pulled him from the water—I got to tell ye that—"

"Gran," Altair said, and took her by one thick sweatered arm and drew her across the well to the other side. "Gran, I got to go, I got to get my boat and take this nice m'ser uptown. And I'll pay you next week."

"You sure you want to go? You want to take me around while you find Suleiman—why, I'd even ride along when you go take the m'ser home."

"Gran, she's right across the way, right over Fishmarket, not a bit of trouble, and I don't want that arthritis to bother you."

"Gran Mintaka," Mondragon said, and fished in his pocket and came up with coin two of which were silver-pale among the copper-dark. "I want you to have this. For the loan of your boat."

Mintaka's face was a cipher in the shadow.

"Will you take it?"

She cupped her hands beneath his, and took the coins. "That be fine," she said, and there was a quaver in her voice."That be right fine."

"I'd like to come back and get that sweater sometime."

"Oh, I be by Miller's Bridge a lot." It was reverence in her voice. It was adoration.

Damn you, Mondragon, you got no heart, lead an old woman on like that. She believes you, you know it?

"Come on," Altair said.

"M'sera," he said to Mintaka, "but say I was small and dark, because if my father knew I was down on Port he'd take his stick to me. There's this girl down there, and our families—It's trouble for her too, do you see?"

4'Oh," said Mintaka, "oh, I do."

"Come on, ser," Altair said, and swept off her cap and beckoned sternly shoreward.

Chapter 6

THE shore was a brick rim that held the tie-rings and made a walk all uneven and shadowy around Ventani's great bulk and the towering triple structure of Fishmarket Bridge. Altair walked along rapidly, dodged her way along the storefront on the corner and headed for the bridgehead and a gleam of light from Moghi's. Till Mondragon caught her by the arm. "That's Fishmarket," he hissed. "That she is."

"Dammit!" It was a whisper, but his voice cracked doing it. "I told you uptown!"

"You want to get there alive?" she hissed back. "We've come in a circle! We're back behind where we started, dammitall! You think it's some damn joke?"

"Shut it down, you want gran to hear? Come on."

"Where are we going?"

"We're going to get you under cover whiles I get my boat. You got any more coin?"

"Some." It was a reasonable voice. Scantly. "For what?"

"How much?"

"I don't damn well know. Maybe a dem in change. I gave you—"

"I just wanted to know." She hooked his arm and slid her fingers down to his hand. "Come on."

"Where are we going?"

"Round here." One of Merovingen-below's rare walkways opened behind the stonework that supported the stair timbers, a dark cut between two buildings that became one building up above. "Leads over to Moghi's. Back way.

You know this place. You ought to. This is where they dumped you off the bridge. Now we can go in here or we can go over the bridge; or we can sort of slip round the Ventani on the other side and I can find you a hole that ain't occupied while I go hunt my boat. But Moghi's is dry and I can deal with him. Which d'you want?"

He had stopped. He had her hand or she had his and he was gentle about it, but she remembered that strength of his.

Lord, Mondragon, you got a twisty mind and I wish I knew which way it was turning.

"Sun's coming up," she said, " 'bout now. See that sky over there? Thatain't fire. Now we can just walk after my boat together if you want. But I got the feeling you'd like to stay out of sight. And you ain't particularly scared of this place, for all it done to you—not when you told me to tie up over there at Hanging Bridge, you didn't."

"I didn't tell you to tie up there. Let me off, I said."

"Well, it's lucky for you I followed you, ain't it?"

He jerked his hand loose and motioned her ahead.

"'S truth," she said; and walked on into the alley. She slipped her hook loose and carried it, the wood crosspiece firm in her fist. In case. She heard Mondragon's steps behind her, grit on stone in this maze that crooked round to Moghi's backside.

The door to the shed there was always unlocked. And strangely nothing got stolen, not so much as a stray bit of wood when the rains washed the boards loose. She pulled the rickety door open and walked in, heard Mondragon still behind her. "Close that."

"It's dark enough as it is."

"You show a light here Moghi'll slit our throats. Close the damn door."

It closed. She found a rope along the wall and pulled it, so that elsewhere in Moghi's rambling little den a bell rang.

"Is this it?"

"Will be. I just rang. They'll come. Don't get so nervous."

"Dammit, I don't take to being kidnapped from one end of town to the other."

"Just go coasting up to Boregy, huh?"

"That's what I thought you'd do, I kept thinking you had some back way in mind; the old woman's boat was the best thing we could have used—no one would look twice at it. Jones is smart, I told myself, I go along with it. Then, no, we weren't going uptown; but you were going to find that boat of yours and we'd get uptown on our own. Dammit, you didn't have to get into that jam-up on the canal if it was going to take all night. Now we've got an old woman telling the tale up and down the city, we've got one more of your damn ideas here, and no boat; and if you think you're playing some damn petty childish trick to hang yourself round my neck, you're playing a damn dangerous game."

There was a hook in her hand. She held that hand still; and drew in a breath and another one and a third before she had her throat under control. "I'd damn well hit you," she said. "I wish I could. Sure, I did it to get back at you. I been doing the work, ye damned lay around, I been waked out of sleep and scorched and flung in the canal and run half dead, and I poled you up and down this damned city till my gut hurts—" Her throat closed up. She tried for air and shoved hard with the heel of her hand when he tried to lay hands on her. "I'll find my boat, dammit, I'll take you to hell, but don't you go telling me how to do it!"

"Jones—"

"You keep your damn hands off me!"

She hit his arm. Hard. The door rattled and opened, and lantern-light glared into their faces. She turned and held up a hand to shade her eyes. "It's Jones," she said.

"Who you got? Who you got?"

"Name's Carlesson."

"Falkenaer?"

"Not him. Hey, I know him, Jep. You c'n let us in. I need that upstairs room. Private stuff."

There was silence. Then a chuckle. "Well. The ice done thawed."

"Shut it down, Jep, and let me talk to Moghi."

"You come right on in." The lantern shifted, held higher. "Ser, you come along and don't mistake us, we're a quiet house."

"They'll kill you," Altair translated. There were men outside by now, blocking the alley; the door beyond Jep was locked. If it had been trouble, the trouble would have gone into a little boat and out to harbor, slip-splash. End of it. But there was no rough talk in Moghi's house. Moghi insisted. And Moghi never tried to take a weapon away from anyone: another rule. Man wants ter carry an arsenal, Moghi would say, that's his business; we don't never argue with a customer.

Slip-splash.

She stepped up to the sill and passed Jep, walked through the cluttered storeroom to the inside door and waited for Jep and Mondragon. Jep bolted up. And the watcher through the peephole inside (Altair always suspected) came and unlocked the inside door.

"'Morning, Ali."

"Morning." Curly-headed Ali blinked in the lanternlight and looked to be in pain, his broad brown face all screwed up. "House just going to sleep with all this ruckus. You got no decency?"

"I want the quiet room, Ali."

"You got the cash?"

"I got it. Now you tell Moghi when he wakes up I'm going to be in and out the front way. And I want my friend here left alone. I'll talk to Moghi about it."

Ali's dark eyes shifted and shifted again in the lantern-light. "Room, huh? Come on. We got one."

Slip-splash. Moghi had another saying about debts.

Or business associates who caused trouble.

The Room Upstairs (there might in fact, Altair thought, be more than one Room) was a tidy place with a lamp– Jep lit it with a certain elegant flair of wrist, from a match in his callused fingers. And a wide bed and a hard chair and a table with a little vase of Chattalen jade flowers (the vase was cheap). No window. One wall was brick, the other three were lathing and plaster.

"Bath's across the hall," Ali said. "Heater's got fuel, water's fine for washing, come from a tank atop: boy empties it, and the can. Drinking water in the jug there. You're paying for a first class room here, we don't stint on nothing." Ali walked over to a tall cabinet. "We got bathrobes, got towels, got genuine brandy here, clean glasses, extra blankets. Boy'll set a breakfast by the door in about an hour. We don't disturb our clients. They don't got to leave the room if they don't want to."

"That's real fine," Altair said.

"You got a little scorch on your face, Jones."

She almost reached; stopped herself. "Sunburn. Been out fishing."

"You want them clothes cleaned up?"

"He will. I got to go out again."

"You can wait," Mondragon said. "Get some food in you."

She did not look at him. "I tell you what," she said to Ali, "you tell Moghi when he wakes up I want to talk to him."

"You going to be having breakfast?"

"I'll have breakfast. I'll be back."

"Jones," Mondragon said.

She left by the open door and never looked back at him.

Down the double turn of stairs, quickly through another door and through a curtain and into Moghi's front room, where the tables were all vacant and the chairs stacked on them for sweeping. A night-lamp burned, and the front door was shut.

She opened that door carefully, and went out into the gray hint of morning, onto Moghi's canalside porch and off those boards again, down the gravelly canalside and up again onto the bricked-up rim. Fishmarket Stair loomed up, triple-tiered; she scanned the shadowy boats tied up beyond the Stair, by Lewyt's second-hand store. Their owners slept mostly down in the hideys, a couple on their halfdeck. There was no sign of Del Suleiman and her boat; and she felt the whole weight of Fishmarket Stair over her head, with constantly the feeling someone might be watching her.

A pale body hurtling off over the rail into the dark. Splash into dark water.

Why no clothes? Why not be sure of him? They damn near burned the town down—what's a knifing more or less?

She walked along—(walk, Jones, don't run, don't draw attention, stroll casual-like, canaler on a shore-jaunt)—the other way, up over Moghi's porch again and along the canalside toward Hanging Bridge.

The usual clutter of canalside homeless huddled asleep against the Ventani's brick wall, where the law would take a stick to them if the law happened by, along the bridge sides. But the law was too few and folk got hit and did it again, till the law got to a bad mood and took them on a boatride to Dead Harbor, to live with the crazies and the rafters. There had never seemed anything threatening about this pathetic sort, until now, until that she walked, helpless and afoot. Now and again a raggedy shape stirred and a pair of eyes fixed on someone who had more than they did.

Boats were tied up along the way. More sleepers, late stirring in this morning after calamity. She came to Hanging Stair and climbed up and up, padded past the Angel with his sword—'Morning, Angel, seen my boat? I know. I'm real sorry. I'm sorry I near burned the city down.

Perhaps the hand clenched tighter on the sword; in this light the Angel's face was grim and remote.

Sleepers lay here too—each one to a nook. She walked along hating the sound of her shod footsteps. She stopped finally in a sleeper-free spot and looked over the rail, scanning the east bank and the boats moored there.

Del was not where he had tied up yesterday. She pushed away from the rail and kept walking.

"Hey." She knocked at the door, stood back so that Mondragon could see her through the peephole. The bolt rattled back. The door opened wide. She limped in without a look at him holding the door.

"Find it?"

4'No." Breakfast was on the table, two of the house's big breakfasts, and her stomach turned over in nauseated exhaustion. Mondragon shut the door and shot the bolt. Mondragon had had his bath. Of course he had had his bath, he stood there in a nice borrowed robe and with the lamplight shining on curling pale hair and the ruddiness of burn about his face. She plumped down on the bed and contemplated her feet. Tears were in her eyes, not pain yet, just the suspicion that behind the numbness there was going to be a great deal of pain. Her feet had dried a bit. Now the right one went squish again, and she suspected why.

"Where would it be?" Mondragon asked.

"Well, if I knew that I'd go there, wouldn't I?"

"I don't know that. You want some breakfast?"

"No." She crossed an ankle over her knee and pulled off the shoe. She peeled down the black sock next, bit by careful bit.

"O Lord, Jones."

She looked curiously at the red stain between her toes and over most of her sole and heel. At missing skin and skin in bloody blistered strips. She changed feet and pulled off the left shoe and sock. It was only rubbed raw. She dropped the shoe and sock and sat there working her toes.

"I heated water for you," Mondragon said. "You want me to help you over there?"

"I just come back from across the bridge, I can walk." She got up and winced her way across the floor to the door, her right foot all sticky on the carpet. She shoved the doorlatch down and hobbled out.

Put her head back in. "You don't come in there," she said.

And slammed the door.

She glumly dressed again in the bathroom, having further business to take care of—new clothes and they looked like old, dusty and stained and the sweater still damp. So was her cap. She carried it in her hand when she went out of the warm little room and limped and winced down the stairs to the tavern-proper.

The help had been putting the chairs to rights when she came in; unshuttered windows and the open front door let sunlight in. Ali was behind the bar, serving a straggle of blear-eyed customers; Ali hooked a thumb toward Moghi's office.

So Ali had indicated when she came back to the front door that Moghi was stirring about. So now Moghi was up to talking. In the office.

She went to that door beside the bar. She had ventured only rarely into that cubbyhole full of papers and bits of this and that, once when she had started work, once when Moghi had told a gangling kid she had a couple of special barrels to handle, because someone who worked for him had taken sick. Fatally. Case of greed. Moghi towered in her memory of that night, bulked larger than reality. And she never could get rid of that shivery feeling when she stood at Moghi's door.

She knocked. "Moghi. It's Jones."

A grunt came back. "Yeah," that was. She shoved the latch down and walked into the cluttered office.

Dusty light streamed through two unshuttered windows– inside shutters folded back against the shelves inside; and thosecould be drop-barred top and bottom, backup to the iron gratings outside the dirty glass. Papers and crates were everywhere, a tide that rose around the littered surface of Moghi's desk. Moghi sat amid it all, a balding, jowled man with massive arms that said even that vast gut was not all fat.

"How you doin', Jones?"

"Good and bad."

He motioned to the well-worn chair by his desk-side. She dragged it over where she could look at him, and sat. Not a sound from Moghi. Her heart was beating hard of a sudden. —Lord, I got to be careful. I got to be real careful.

"Need your help," she said. "I got a boat missing."

"Where'd you leave it?"

"Del Suleiman, by Hanging Bridge."

"That all you need?"

"Quiet. Lot of quiet. It'd be real nice if that boat just showed up to the porch tonight."

Moghi's seam of a mouth went straight; his jaw clamped and calculation went on in his murky eyes. "Well, now, you come up in life, Jones, up there in the Room. Real pretty fellow, so I hear. And you a canaler. Now I know somehow you c'n afford all this. I got standing orders, anybody asks for that room, they gets it. And we don't talk about money. You get fancy stuff. You want a bottle of something special, you just tell the boys; you want a little favor, you just tell me. If there's expenses above and beyond I add 'em to the tab. You know me. I never ask into private business. It's characterI ask about. You I got no doubts of. But what's this pretty boy you took up with?"

"He's real quiet."

"Now that's nice to hear. But you know there's lots of trouble in town. Lots. And here comes Jones with money—I know you got money, Jones, you wouldn't run a tab you couldn't pay—and you got this pretty feller and you mislaid your boat. Now, I don't ask into your business. But look at things from my side. Would you want to take in a fellow you don't know right about now? I don't like noise. I sure don't want the blacklegs chasing nobody in here."

"Moghi." She lifted her right hand. "I swear. No blacklegs."

"What's his trouble?"

"Six guys trying to kill him."

"Ali says he talks real nice."

"He's no canaler."

"Now, Jones, you know there's a lot of difference there. Man has a set-to with the gangs, that's a little problem. Gang goes after an uptowner—big money's hired 'em. You c'n figure that all by yourself. You want to tell me, Jones; this nice-talking feller done talked nice to you? Maybe got you twisted all round? Maybe got hisself where nobody ever got with you, huh?"

Her face burned. "I ain't stupid, Moghi."

"Now you and me ain't talked since you was a kid.

Lord, first time I saw you, you went round in them baggy pants with that cap down round your ears—your ma lately dead; and I set you up with old Hafiz, didn't I? He didn't want to deal with no kid, had this feller all set up to do that job—some fellow going to do things a bit on old Hafiz' side, huh? And I told you then—what'd I tell you, Jones?"

"Said if I wasn't smarter that man'd send me to the bottom."