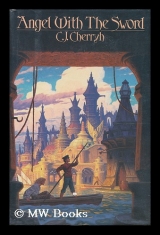

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Bells happened many times a night in Merovingen. A shop got broken into, a shopkeeper hailed the blacklegs and his neighbors. Nothing unusual.

But she cursed and got the knot loose, stood up and rattled and fumbled with the pole as she ran it out, gritting her teeth against the pain of her arms. She nearly had her legs go out from under her as she skipped down into the well and hurried up forward to put the pole in and turn the skip about.

"Jones." It was Del. Del had made it back to his boat, Mira panting a distance behind. "Jones, I got to talk to you. Mira—"

"I ain't got time." She fended a bit from Del's boat, shoved the bow out against the Snake's current and let the current slew her hard as she ran back to stern again, getting underway.

"Jones," Del called out. And: "Altair!" from Mira.

"Where's she going?" someone asked.

Water lapped noisily at the sides of Bogar and Mantovan, and voices dimmed as she came out and got moving.

Damn fool panic, ain't no cause of it, folk'll see you.

Slow down, Retribution said in her mind. You want those fools back there to see you run like this? What you thinking of, Altair?

I dunno, I dunno, mama. I don't care, damn them all. I got to get back again to Moghi's. I got to find Mondragon, something's wrong, something's wrong somewhere.

And wrong's got this way of finding him.

Breath came hard, came on an edge of grinding pain as the pilings of Hanging Bridge closed all about her, with the skip riding the Snake current. No boats, her eye picked up not a single skip or poleboat moored under Hanging Bridge, nowhere about the point—there had been a single skip making its slow way down the Margrave, under Coffin Bridge. No one else. The desertion was ominous, but the boats that belonged hereabouts were mostly down at Bogar—Council called was a good enough draw to account for scarce boats: she had seen it scarcer on a rumor or a wedding or a wake—A hundred reasons.

Past Hanging Bridge shadow. Ventani Pier loomed blackly into the sheen of water and bright light glittered on the water in front of Moghi's open door, showed a half-dozen or so boats moored to Moghi's porch. Thatwas normal. The windows were unshuttered, the door wide.

Fool. See? Kill yourself for nothing. Mondragon's abed, sleeping all nice and warm and never knowing a thing.

Got to get him up and moving. Got to get him up to Boregy fast as we can. Lord, my arms, my hand. Oh, damn, damn, my finger hurts.

But where's the music?

Where's the noise?

I ain't hearing music, not a voice. O Lord! Lord—why ain't there any noise yonder?

She poled another stroke, let the skip glide, wind cooling her skin through the sweater.

Tie up to the porch, slip round back, by the shed?

Walk that dark cut, back into who knows what kind of trap?

O Lord, O Lord! It washere, it wasMoghi's bell– Where's the watch? Ain't the damn blacklegs going to come?

What'm I going into?

She veered off toward Ventani Pier, so sharply the skip crabbed along sideways and made way slowly toward that dark set of pilings and the sloping freight-dock.

Her mouth tasted of blood. Her ribs ached. She drove in hard toward the pilings, scraped the skip side against them so hard it staggered her in her footing.

No watchers along the stone rim. No homeless and no mendicants waiting there to pilfer a boat's goods. Nothing. The poor and the cats—they knew when to move. They had more sense than a fool canaler, than a meddler in others' business. They were gone. Safe. They saw nothing. And everything.

She turned the bow again and poled along the dark, shallow edge up to the south side of Moghi's porch, snagged a piling rope with the barrel hook, wrapped the portside tie around it and scrambled up the ladder in the light and the unnatural quiet from inside.

She stopped dead in her tracks then, numb at the sight of bodies all over the well-lit floor, slumped at tables, in chairs, as if catastrophe had been sudden and violent,

"Moghi!" She wavered there in the impulse to run, to bolt back to the safety of her own boat and take herself where a canaler belonged.

But Mondragon—but him, asleep upstairs—

She took her knife and her hook in either hand and walked in, looking this way and that, finding nothing astir. She walked the length of the room, through puddles of spilled drinks. There was a lingering acrid smell, a haziness in the air. The smell made her head ache.

Through the back curtain, into the hall, and through that narrow doorway where the stairs were. Another body. More bodies. One moved.

"Ali!" She got to one unsteady knee and shook at him. "Ali! What happened? Where's Moghi? What's—"

"Uhhnn," Ali said, and raised a hand to point upstairs. It fell again. He made another effort. There was blood on his mouth. "Moghi—out back—" He was trying to get up. Altair left him and scrambled up the stairs.

The door of the Room was open. She ran to it, ran inside, where the nightlight still burned and the bedclothes lay ripped half from the bed. She ran to the other side of the bed, and there was nothing lying there but Mondragon's sword.

She flung the bedclothes this way and that. Not a trace of blood, nowhere any blood. Or of Mondragon's clothes, except the knit cap. Thathung there. No boots. So he had been dressed when the trouble came. He had not been taken asleep. But he had been dragged across that bed– someonehad.

She grabbed up the sword in her hook-hand and went back around the end of the bed to discover her own shoes still lying where she had left them. She squatted there and shook out the one with her knife hand.

The gold piece thudded out onto the floor, lay mere shining in the lamplight.

So they—They—had not bothered to rob, either. Had not searched the place at all. It was nothing in the world they cared about but Mondragon himself—so they were not ordinary thieves, not hired help; and him gone without a trace of a struggle but the bedclothes ripped and the sword lying and the air filled with that acrid stench.

She pocketed the goldpiece, sheathed the useless knife and hook and pelted barefoot across the hall to check the bath, in one last vain thought of finding him.

Nothing. Her head pounded, her eyes watered and her nose ran—she swiped her sweater-sleeve across the latter, hearing a commotion below, men's voices and muffled oaths.

They were alive down there. Whatever noxious stuff had gotten loose in the building, someone was alive, and someone was down there walking around.

If it was not the Sword of God themselves, come back to kill them all.

O Lord, ain't nobody heard that bell? Don't even Ventani care, upstairs of us? Governor's police won't come, they won't about come down here, 'cepting they might want their hands on Mondragon—

–and now there's me, up here in the upstairs with no way down but them stairs—

There were clear voices and muzzy ones, all male; then:

"Jones!"

Moghi's distinct bellow, however strained and cracked. She clenched her fist on Mondragon's sword and headed stairward.

Moghi was down in the hall, propped on a bench against the hanging clutter of clothes and towels on the wall. Ali was there, with a half dozen of the bullylads and a single youth whose lavender-and-black silk shirt and outraged manner said Ventani all over him. Upstairs had come to call—the Ventani landlords sent to know what was amiss down in their basement and why the bell had rung. From the room beyond came thumps and weak oaths. A chair scraped and crashed. The pretty boy from Upstairs Ventani looked anxiously up at her and said something to Moghi: then he hurried out, avoiding witnesses, even if it was no more than a canaler headed downstairs with an uptowner's sword in her hand. Ventani got itself clear. It wouldbe clear, if and when the law came calling. Ventani would see to that.

"He there?" Moghi asked, a ghost of his ordinary voice. The handful of men hovered around him, all of them with dour, ugly looks " He there, Jones?"

She clutched the sword in her left fist and stopped on the bottom steps, outnumbered and outweighed and with no more place to run than canaler justice gave her. Not raise a sword against Moghi, nor take a hook to him. That was a way to die, right off or in a few days, slow and painfully.

"No," she said. "He ain't there." And stamped the last two steps down to stand square in Moghi's little court. 4'Dammit, Moghi—how'd they get him?*'

"Smoke," Moghi said, "this damn smoke—" He waved a pasty-hued hand. Sweat stood on his face. He looked like a man about to be sick. "They came in, all hoods and masks—Wesh got to the bell and they flung one of them Chat stars—Wesh's 'bout dead out there—" Moghi coughed, the spasm rocking his whole body. "Ain't seen Tommy or Jep. Damn them. Damn 'em anyhow!"

"I got to get help—*'

"Ain't no help going to come—Ain't no blacklegs going to mix in this."

"Well see about that." She started past, for the door, but that door got blocked. Two men moved into it. She turned around and looked Moghi's way. "I got to find 'im!"

"Wait," Moghi said. "Jones. Come back here."

She came. With that tone of voice, with Moghi's men in the way, she had no choice. She stood in front of Moghi and Moghi's mouth made a thin pale line in his sweating face.

"You going after him," Moghi said. "You know what you're after?"

"I got names. Boregy. Malvino. They c'n get help somewheres." She squatted down on her heels, the sword across her knees, so that Moghi did not have to look up. "They got gold to buy trouble for them bastards, they can get him back."

"They ain't no gang," Moghi said, his voice all hoarse. "I seen 'em walk in—bold as boils, them and them black masks—never spoke a word, just this smoking pot rolled through the door and these black devils came through, just walked through, with customers dropping to the floor and that damn smoke—They flung a star at Wesh. Old Lewy cussed 'em and I thought he was gone, but they walked on through like they knew where they was going—They damn well knew, Jones."

"Well, I never told 'em!"

"They walk in here like they own it all, like they know where they's going—They ain't no gang, Jones, they ain't nothing like that."

"I got t'other half of what I give you." She fished desperately in her pocket and came up with the gold piece. "Moghi, I pay ye, I make it good as I can, I go away."

Moghi hesitated, staring at the gold round—just staring at it and not taking it, as if Moghi had ever hesitated at money in his life. Then he clamped his jaw tight, reached out a waxy hand and took it between two fingers to carry it back and hold it up. "You 'member what I said, the time you come in here looking to haul barrels, Jones? You 'member what I told you about that, how I give you them two silvers and put you up against that bullyboy of Hafiz's? You 'member what I said? If you got the load back you was hired and if you got to harbor-bottom I had me an excuse."

"I come back, Moghi."

"I want these black fellows' guts on a hook, Jones. I ain't expecting to see you again. But I'm turning you loose. Ain't no lot of hooded bullies come into myplace and take none of my guests. I'll have their guts for breakfast, ain't no way they get away with that. Now you tell me, Jones—" He reached out and carefully gathered the neck of her sweater in his fist and pulled her close, up in his whiskey-laden breath. The sword was still in her lap; she dared not touch it, more than to keep it from falling. "Jones, you tell me true—everything. Or I gut ye. And you tell me ever'thing and I give you the same bet I give you five years ago—I give you anything you need. This ain't a money-thing. This is killing. You understand me, 'Jones? Who is he? What's these black fellers? Why'd they bust up my bar and poison my customers?"

"Sword of God." The breath came out strangled, choked on its way; Moghi meant it. meant it about the killing and meant it about sending her out. It was in his eyes that stared into hers, it was in the fist that held her sweater and shook with rage. "Sword of God – He run afoul of 'em, he run from somewheres north, I think—he's a rich man, Moghi, I never lied. He's got rich friends, he's got money– You'll get it back—"

"It ain't money." The fist tightened more, twisted at the sweater and cut off her wind. "You going to go to them friends, are you?"

"Yes."

"Sword of God." He shook her. Her eyes rattled in their sockets. She went to her knees and the sword hit the floor between them. "Sword of God! Why d'they want him? Huh?"

"I think—" Another shake. Her brain reeled. "I think they want to shut him up. He—knows too much."

"They ain't killed him! They took him right out the front door! Right in front of ever'one, they took him away!"

"Then—I dunno, Moghi, I dunno. I think they want him back."

"Back!"

"I dunno, Moghi!"

The fist relaxed, slowly. Moghi's face stayed all white and hectic-flushed and beaded with sweat.

"You said—" Altair sucked a mouthful of whiskey-tainted air. "You said you'd give me what I need. Give me a can of fuel. Give me one of your boys to go with me—Moghi, my arms is like to break, I poled from one end of this damn town to the other—I got to get uptown, Moghi, I got to be able to run."

"Folk'll think I'm getting old. Folk'll think they can walk in here anytime and cause trouble. Folk'll think they can do any damn thing they like to my boys in the town– Damn them, damn them anyhow! You get your fuel, you get any damn thing you want, Jones. And you get back here with what you find out, you let me know it, hear?"

"I hear you, I hear you, Moghi."

"Get two of them cans," Moghi said, motioning back at the storeroom. "Mako, Killy, all o' you, you get that stuff out to her boat. Jones, you go out there, you get that boat round to the landing, you get yourself uptown and you get them rich folks moving. And you be careful, Jones, or I'll sink ye!"

She grabbed Mondragon's sword, scrambled up and pushed her way through the men around Moghi, past Ali, who delayed bewildered in the doorway. She jogged out through the common-room, where dazed customers showed life, where several were busy heaving up their stomachs where they lay. Canalers. She saw familiar faces, saw one in the doorway, young and pimply-faced and spiky-haired, staring at the scene as if his wits had left him.

"Tommy!" She grabbed his skinny arm and shook him till his eyes showed he knew her. "Tommy! There's a lot of canalers off by Bogar Cut! You run, hear me, you run and tell 'em what happened here, run say I said there's a blond man been carried off by them as poisoned folks here– hear me, Tommy?"

"Yeah," Tommy said through the chattering of his teeth.

"Moghi's alive. He'll skin you if you don't, hear that? Tell 'em report to Moghi, tell 'em to come here with what they know. Hear?"

"Huuuh," Tommy said when she shook him.

"Then git!"

He got. He turned and ran, was halfway to Hanging Bridge by the time she got down the porch ladder to her deck and looked to see. She shoved Mondragon's sword into the hidey, jerked the tie loose, ran out the pole and backed-Easy, Jones, use the wits, Jones. Hurry don't never move a boat from dead-stop.

She got it maneuvered around, used a shove from the bow and ran back to the halfdeck, fending from this and that piling, while a to-do down by the darker, deeper maze under the main bridgehead told her where Moghi's men were. She eased in there, and a hook out of the dark snagged her bow and helped her bring the bow in to the dark landing-slip.

Men brought two cans aboard, walked down to the slats, setting the skip to rocking—"You set one here," she said, tapping the spot with the pole-end. "You there—get 'er up here, tip 'er into the intake, she'll hold it." She racked the pole and hurried to fling up the engine cover to get at the fuel intake. A flip of the cap and Moghi's man unstopped the can and heaved the whole can nozzle-down into the intake, a fumy flood that gurgled into the empty tank.

If I'd've had time to work on the engine, if I could count on 'er starting, Lord and glory, I can't trust that thing less she's running and I known her to die outright when she goes cranky.

Thelast of the fuel spilled in. The man took the can and headed off the halfdeck in haste. "Who's staying?" she asked, seeing one and another man quit the deck. "Who's going with me?"

"It's me," a voice said, all hoarse and wobbly, and a smallish curly-headed man staggered his way up to his feet. "Moghi said."

"Ali?"

"I don't like boats," Ali said. "Jones, my belly hurts. My head's killing me."

"Damn, damn—" Thatwas Moghi's help. The refuse. A man too sick to crawl. She ran out the pole again, feeling the boat let loose from its grapple up forward. "Get the boat hook," she said to Ali."

"We poling!"

"We ain't going to run the motor and get them black bandits on our trail out of here, are we? Get that damn hook!"

Ali staggered to the rack and got the hook. "I dunno how," he said. "Jones, I ain't no—"

"Ye stroke opposite me up to bow and ye don't fall in, ye useless baggage! Ye just don't fall in, or I swear I'll leave ye to drown!" She shoved with the pole. "We got upcurrent to fight, damn ye, shove!''

Ali got to point and got the blunt end of the hook in. It was not much of a push, but it helped; breeze at their backs helped. She counted for him—"hin, Ali, hin, dammit, ain't you got no feeling what I'm doing?" —and drove with all the strength left in her shoulders and her back. "Get back to here, get back here aft and move 'er, man."

Then there was just breath enough to push with, and none left for talk. There were her gasps and Ali's, and the slap of the water as the skip moved along at all the speed one poler and unskilled help could manage.

Damn 'em. Damn 'em all.

No boots. Mondragon had lain down to sleep but he had never undressed again—he must'vebeen asleep and not heard the fracas below, til the smoke got to his door, til he was trapped in that room and the smoke got inside it.

She built a picture in her mind—Mondragon lying fully-clothed abed after she had gone. Falling back to sleep lying atop the covers til the smoke got to him and he knew something was wrong, til his kidnappers broke the door in and he put up a last railing defense, the sword falling to the floor on the far side of the bed as they overpowered him, a struggle that tore the sheets free and strewed them outward toward the door—

But the boots. The boots were gone. And the door—she did not remember any splintering about the doorframe.

A knock at the door? Mondragon being called to the door by a voice he knew—surprised and borne backward in a struggle that ended in a wild dive for the sword—

Mondragon handing her the money he had left. Holding the boot in his hand and complaining about her intentions.

Had he gone on to finish dressing?

She gasped for air and looked over to Ali—to the one who came and went in Moghi's Upstairs Room. "They get Jep?"

Ali turned a sickly, widemouthed grimace her way. "Dunno." Between breaths.

"You see 'em?"

"I saw 'em—Yow!" Ali wobbled, hanging his pole, and flailed wildly for balance on the edge of the deck. She crossed over and grabbed him by the back of the shirt.

"Who? How'd they get up there?"

"I dunno!" He swung about and his elbow grazed her ribs as she sucked air and skipped back. "I dunno!"

"I'll give that report to Moghi," She gripped the pole crosswise as she faced him. He had the boathook, but no landsman could use it right. "You want to try me with that thing?"

"You gone crazy?"

" How'd they get in? Why'd my partner have his boots on?"

"I dunno, I never saw—"

"Was it Moghi himself?"

"Front door." Ali's teeth chattered. "D-d-amn door was open, they walked in—"

"Smoke went off in the upstairs hall too. Didn't it?"

"Jep—Jep—done it."

" Youdid, ye damn sneak!"

He swung the boathook at her. She swung. Down. Ali slumped on the deck like a sack of meal, and she hit him with the pole-end when he showed signs of getting to his knees. The boathook rolled aft. She stamped on the pole and stopped it, No further sign of movement from Ali.

She gathered up the boathook and shoved Ali with her foot, thump, down into the well. He landed on his shoulders and twisted up.

"Damn! Moghi?"

No. Moghi weren't lying, that weren't no lie, I knowhim, I ought to take this traitor back to Moghi and let Moghi get truth out of him.

Lord, Lord, they got Mondragon somewheres, they want him alive—

What'll they be doing to him?

The timbers of Southtown Bridge hove up ahead. Canalers were night-tied there, along by Calliste. She put the pole in and shoved off in that direction, driving on pain in her ribs and pain in her arms. She came gliding in and fended off a poleboat with a clumsy scrape of hull against hull.

"' Damn fool!" a male voice yelled, a sleeper startled out of slumber with collision and damage to his boat,

"Name's Jones," she gasped, and squatted down there in the dark and tried to keep the skip immobile. "'I got to have help."

"Help– Jones, Jones, is it? There's a word out on you. You set that fire."

"Damned if I set it! I got that straight with Jobe an hour ago!"

"I ain't having no part of your business!"

"Go on!" someone else cried from another boat. "That's Jones, a'right. That's her what burned Mars Bridge!"

"You keep your distance!" She shoved with the pole and put water between her and the poleboatman. "This lander tried to kill me. There's been a fight down to Moghi's. This baggage of mine poisoned a dozen canalers, he's took a bribe from someone—Oh, damn!" There was life from the well. She sprang up and swung the pole, a sweeping crack across Ali's ribs—"Yow!" Ali screamed, and cartwheeled right out of the boat with a great splash of water.

"There," she said, "you better fish him out, I don't know if he swims!" She put the pole in and shoved off, and shoved again, with Ali flailing the water and choking in great shouts and gulps. "I don't think he does swim!" she amended that. "You tell Moghi ask him how come my partner didn't put up no fight and why that door weren't broke in! That fellow's worth money, there!"

More and more water between them. She faced about and kicked the engine cover up, primed it and pulled the choke and made the first try while shouts rose behind her. Thump, into a piling. The skip slewed around, dizzily following the current.

"Get after her!" someone yelled. "She's trying to start that engine."

Second try. Cough, tunk.

Come on, engine.

She heard the splashes, heard Ali screaming, heard boats moving. She never looked. She reset the choke. Tried again. Cougn-cough-chug-tunktunk.

She feathered it down, engaged the propeller and it faltered. Held. The skip lumbered forward, aimed at open water. Screams diminished over the noise of the engine.

She pulled the pin and got the rudder down; pulled the second pin and got the tiller up and home. She leaned on the bar and swung round as two canalers moved their boats out to stop her, stringing out from moorings.

Not fast enough. She put the throttle down and the engine lumbered away with more and more way on the skip. She let the pole lie abandoned on the deck, slanted into the well, put the tiller over hard to choose a clear way through the pilings of Southtown Bridge, and powered through. She looked back, where an unaccustomed white wake showed in the moonlight, and ahead where Foundry Bridge was.

All about her, boats were moored along the bridgehead, wherever the projection of pilings gave them shelter out of the Grand channel. All about her, eyes would peer into the dark and the commotion would spread. She thought of dodging round into Foundry Canal, getting at Boregy the quiet way—but there wasno quiet way, canalers could cut her off, block any canal but the wide, free-flowing Grand.

She put the throttle in full and spent fuel recklessly, took time to rack the poles when there was a moment's straightway between Foundry and Hightown bridges, and got back to the tiller before it slewed in the current.

Boregy had already been hit once. Opposite the Signeury. So much for town authorities and the governor and all his militia. Damnfool and his clockmaker son and his whole damn pet police.

The night kept its false quiet, with only the sound of one boat engine running hard through the town heart, alerting every enemy that might be watching and listening.