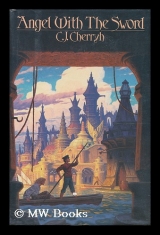

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

didcome and go with some regularity. The Signeury knows. It's just never been worth the bother."

Go to hell, Kalugin.

"So you were waiting in the harbor," Mondragon said.

"I was waiting. You see that not much passes by me."

"You make the point successfully."

"I'm glad. I plan to survive both my sibs. I want you to appreciate that fact. The terms, Mondragon. I'm going to turn you loose. Both of you. There's your skip, m'sera, tied to the Nikolaev yacht, in full view of God and everyone. I'm a guest of the Nikolaevs, no secret. There will be the gossip of your three companions. And should imagination utterly fail this town, my agents will loose certain vague rumors concerning your attachment to me and the fate of opposition who might think to lay hands on you. Do you see? If you serve my interests you'll find my arm is very long to protect you. Betray those interests in any particular or give me one false piece of information in our interviews and you'll discover the same. Does that satisfy you, m'sera? Will you not firebomb Kalugin?"

She shivered. Clenched her hands and drew a deep breath. O God. Alive. Outof this place alive. Mondragon, what's truth? What's a lie, from the devil?

"I don't need to wait till the rain stops, m'ser."

"What, not stay and enjoy Mondragon's I'm sure very entertaining company for the while?"

"You said you were letting him go!"

"Oh, but afterhe's told me all I want to hear. After he's sat with me and gone over my maps and helped me make my lists, m'sera."

"We're back to the beginning," Mondragon said. "You letting her go. Me here—not knowing what your word is worth."

"Oh, but she could stay. And you'd still wonder whether you'd leave alive. You have to trust me. In that little thing."

Mondragon reached for the brandy and drank it down to nothing. Set the empty glass down. "Compromise. She'll leave a message daily. At Moghi's, on Ventani. Your agents will deliver one from me."

"Elaborate. Wasteful."

"It gets her out of here."

"It gives her a chance to go to hiding if you slip her a suspicion of bad faith. Of course it does. I don't doubt you'll think of other little nuisances. Like telling her everything."

"I'm glad it was you who said that. I don't want you to think I have."

Kalugin sat expressionless a moment, then once and sharply an eyebrow twitched. "Very reckless, Mondragon."

"I'm quite serious."

"I'm sure you are. I also doubt you could have told her everything. I'm sure m'sera's expertise in statecraft has its limits; and her ability with maps probably greater limits. No, m'sera. Is your boat in running order?"

"Tank's holed; got a hole in her bottom, too. It's how you damn well caught us."

"Jones."

"I believe m'sera. A hole in the tank and a hole in the bottom. I don't think that should present much of a problem. Some of my staff will go down with you. I'm sure Rimmon is adequate to a repair of that size. You did say you had no need to wait on the weather."

"I changed my mind. I c'n wait. I c'n wait here a whole week. Two weeks."

"You'd not want to complicate matters. No, m'sera. I'm very anxious to have our friend's undivided attention. Your engine running. Supplies as you need them. Money if you require it. You arein my employ."

The hell I am. The hell I am if you lay a hand to him. I'll have your guts on a hook, Kalugin.

"M'sera, do you understand the arrangement? Each morning without fail, you'll leave a note with the Ventani tavern. Each morning a man will take that away. You do write, m'sera?"

"I write. I ain't got nothing to write on."

"Supplies. It's very simple. All that sort of thing is very simple. My staff takes care of details. All you have to do is ask. But you have to go now, m'sera, I very much regret, without any private word between you. This man would do something devious, I'm well sure, and I don't want you to bear that burden. Just say a public goodbye and go gather your belongings."

She looked at Mondragon. He nodded, with a private motion of the eyes. Truth, then. Go. Get out. Her eyes suddenly stung and threatened to spill over. She shoved herself to her feet.

Can't damn well walk. I can't walk, my legs'll go.

Mondragon reached his hand out. Took hers and squeezed it. She found life for her fingers and squeezed back till he let go. Fingers trailed apart.

She walked a few steps, looked back at Mondragon's back and Kalugin's white face above that ruby collar and black shirt—set her left hand on her hip, brushing her sweater aside, and cast what she pulled up.

The glass blade hit the carpet well to the side of Kalugin's chair and broke in half as guns came out of holsters all around the edge of the room. Mondragon started from his chair, stopped motionless as everyone else.

"That," she said, with heat all over where the cold had been, "that was in case."

She turned and walked out. "Sit down," she heard Kalugin say behind her. She heard guns go back into holsters and several men walk after her.

Can't hurt me. Yet. They got to have them letters, don't they?"

Moghi had a down look this morning, Moghi behind the bar himself this breakfast-time, his sullen jowls all set in a tuck of his chin as he polished away at glasses. Ali stopped his sweeping—Ali with the last traces of his black eye; and started it up again when Altair looked his way.

She went up to the bar with tomorrow's letter, all done up with yarn-tie, and there seemed an uncommon quiet about the tavern's morning patrons too, poleboatmen and Ventani regulars, mostly, having their breakfasts. They knew her. Everyone in Merovingen-below knew Altair Jones and knew mysterious letters passed between her and an uptowner-man who came to Moghi's every morning.

"It ain't here," Moghi said, and polished away at a glass too scratched to be helped, "Ain't come yet."

"What time is it?"

"Dunno, 'bout time."

She stood there a moment. Put the letter on the counter. Her hand shook when she did it. "Well, put that with my other. Man can take 'em both. Just late, that's all."

"Right," Moghi said. "Have an egg. On the house."

Generosity. From Moghi. Moghi thought it was bad.

"Thanks. Thanks." She walked back through the rear door to the kitchen, "Tea and egg," she said, and Jep gave her a look. "No," she said, "it ain't come."

"Unh." Jep got a gray-speckled egg from the tray, looked it over and got a second one. Broke them both onto the grill and added a slice of bread.

She slouched over and got the plate when the food came off. Took that and a cup of tea back to the main room and sat down to eat it.

Late. That's all it is, just late, they got some kind of tangle-up, some damned hire-on taking his damn time.

Eat your breakfast, Jones, damnfool, it don't cost you nothing.

She pushed the egg around on the plate, ate it in too-large bites and got the bread and tea down.

She waited. The boy came and tilled up her tea again and she drank that.

Damnfools, staring at me.

She shoved the chair back finally, a scrape on the wooden floor. Walked over by the bar and had Moghi's attention before she got there. "Going for a walk," she said. "I'll be back in a while."

"Huh," Moghi said, and went on arranging his glasses.

She walked out the door into the full daylight, pulled her cap tightly down and stared out over the morning-gray waters of the Grand, between Fishmarket's towering span and the plainer gray wood of Hanging Bridge. Skips were gathered there, gathered at Fishmarket's far side; a couple of poleboatmen came out of Moghi's at her back and headed down the ladder to the boats moored at Moghi's porch, a gathering like so many black fish with her own bigger boat moored beyond.

"Hey," she yelled from the porch, "you back out all right, you want me back my skip?"

"Ney, we got room."

It was tight. The poleboats began to move out, one and the other. More boatmen came out from Moghi's, talking the day's business.

Damn. Never figured to be tied up that long.

"I move 'er," she muttered, and climbed down the ladder, walked across half a dozen tightly-packed poleboats and the length of one, stepped into her own bow and slipped the jury-tie. Boats backed, taking their own time about it. She kept the skip still with the pole, worked into a developing gap at the porch edge and racked the pole, moved fast to grab the bow-rope and tied on in the last ebb of poleboatmen outward bound and the retreating clogs-onboard thunder of shoresiders on their way to their shops.

She retreated to the stern and sat down on the halfdeck-rim, got the bluestone out of its storage by her foot, took out her thin-bladed knife and set to sharpening it since yesterday's use on a bit of line.

Damn hightowner sense of time.

I give 'im another hour.

Then I got to think of something. I got to get to Rimmon, that's what I got to do.

No. I find where Kalugin is. He's slippery. Could be in Nikolaev. Could be back to Kalugin. I don't do nothing stupid, just real slow and calm.

I give 'em a little present like I give that slaver-boat, they got to come running out. And me and this is waiting.

The blade blurred.

I give 'im an hour, then I got to go somewhere they don't find me so easy.

Water fell onto the steel. She wiped her eyes with the back of the knife-hand and kept to polishing.

Leather-shod steps came up onto the porch, reached porch-edge and stopped. She looked up at a blurred outline of a man in uptorn clothes standing there above. Blinked and saw the daylight catch the hair and hover there.

M'God.

M'God. She sheathed the knife, dropped the stone and got to her feet in the well, staring up at the elegant man on the porch, the man who took the ladder-rail and came down it to step off onto the slats of her well.

He looked all right. He stood there as if he no longer knew his balance on a skip. Pretty sword at his side. Nice clothes.

You get along with Kalugin all right, then, Mondragon?

"Jones—"

All pretty again. You got an eel's turns, sure enough. Woman breaks her heart over you and you come back smelling like an uptowner, and no mark on you.

"Got room for a passenger?"

"Hey, I ain't loaded. You going somewhere's in particular, dressed like that?"

"Jones, dammit."

She pushed her cap back and resettled it, wiped her fingers on her sweater. "You're looking all right."

"I'm all right."

"You leaving town?"

"No, I—" He gestured vaguely toward uptown, motion of a lace-cuffed hand. "I'm staying in Boregy. Till I can find somewhere else. Moved late last night. Boregy's boat delivered me down at the corner—" His voice trailed off. "I'm late, aren't I?"

"Hell, not much." Her eyelashes prickled with damp when she blinked. Damnfool man. Can he tell I was crying? Did he see me? "You look real nice."

"You too." He came close to her, all perfume-smelling, all clean and fancy lace-front and wool coat, and she backed and held her knife-blacked hands out of the way as her leg hit the half-deck. "Jones, let's go somewhere."

She stared at him. "You in hire to Kalugin, are you?"

A little tautness came to his mouth. "I have a patron. That's the way a foreigner lives in this town."

"Damn, you trust that—"

"He's very likely to be governor someday. I know his kind. They often win."

"Yey. They do."

"I haven't got a choice, Jones."

She drew several quick, short breaths. "Huh." She wiped her hands again. "Well, that's another thing, ain't it?"

"You want me to untie?"

She blinked, flung up a bewildered gesture. "Hell, uptowner don't do the work." She edged past him, went her barefoot way forward and jerked the tie. Looked up at Ali standing there on the porch rim. At Jep behind him. "Dammit, ye looking for gossip?" She waved a go-away at them. "Tell Moghi I got 'im!"

"Where you going, Jones?" Moghi's voice bellowed out.

"I dunno. Ware, aft!" She unracked the pole and pushed off. "We'll know it when we get there." Pole down. The bow came about into Fishmarket shadow, for up-Grand.

"And don't you dare open them letters, Moghi! I know how I tied them knots!"

APPENDIX

Of Union, Alliance, and Merovin A Concise History of Merovin

THE history of Merovin is a history of mistake. There was from early in Alliance and Union history (2530 AD) a proclamation colloquially known as the Gehenna Doctrine: it declared as a matter of policy that no Terran genetic material should be introduced into any compatible alien ecology; and that humanity should not contact any alien species onworld, and should not land on any planet unless invited by a dominant sapient species. The practical sense of it was this: that humanity would keep to space and leave developing worlds free to develop without contamination traveling in either direction; and that humanity would contact no species that had not advanced into spaceflight. The theory behind this was that such a species had (1) avoided blowing itself up with advanced power systems and (2) learned enough about its own planetary ecology to devise protections against contamination at critical levels. The Gehenna Doctrine guided humanity in the twenty sixth century; by the twenty seventh, it was suffering some erosion. Humanity spread out not in a coherent sphere from Earth, but outward from Tau Ceti and in the general direction of Vega and Sinus in thin threads of lanes along routes ships could use, to stars humankind could use; and the lack of centralization spelled lack of central control.

Of the two human superpowers, Alliance (near the center of human space) was more nearly a coherent territory and actually had a coherent government. Union spread outward in a series of threads that more resembled a network of corridors of diminishing cohesiveness; Union realized early on that it was never going to bea coherent, compact government, that it was doomed to sprawl. It had taken certain educational measures with its citizens to assure an underlying conformity (Alliance called it mind-washing) and simply shrugged as the lines of colonization extended outward beyond its reach or understanding. Union asked peace of its component parts; and violated the Gehenna Doctrine not as collective policy (it had none) but locally. In effect Union applied the Gehenna Doctrine to humanity more than to alien contacts: it cared very little what went on within a local unit, down an isolate star lane, or on a particular world—as long as what exited that unit and came into another unit's space left its neighbors alone and generally obeyed Union law.

Merovingen was an example of the kind of accident Union was prone to: a wildcat colony launched in 2608 by someone far from Union's capital at Cyteen, at a little G-class star with an earthlike planet—just too attractive for certain economic interests to resist. It was a general period of expansion, and in the confidence of new science, worlds were no longer exempt.

The expedition moved in haste at all levels, worried about attracting attention from upper levels of the Union super-government (under the general apprehension that the Government tended to take interest in anything that went on too long and with too much local disruption). This haste had a foreseeable consequence: hasty geologic reports, hasty climatological studies, objections from field officers stifled by superiors whose superiors might be distressed if schedules were not met. Hasty zonal survey.

And a very illegal coverup of what the colonial officials tried to call a natural formation; fracture patterns. A geologist objected and found himself grounded. No archaeologist was consulted at all; it was quite evident that whatever it was, was deeply buried, thoroughly abandoned, and of no consequence to the colony. Someone a long time ago had colonized the world and abandoned it. That was the opinion behind the most securitied doors in the survey mission. And basaltic formationwas the word that got beyond those doors. Listening scan of nearby stars picked up no aliens and no activity. The world had none. It was all very safe. The people and the higher echelons did not have to know, until, well—later. Afterthe colony was in place.

Things went quite smoothly—like a fall over a cliff. The colonists debarked, built and built, the crops thrived, the colony achieved level II industry, the space station added new sections, the shuttle port enlarged its perimeters, the promoters became rich, and the companies back at the parent star were all smiles and complacency.

Thenthe former landlords showed up.

Sharrh was the name they called themselves. They communicated with humans in 2652: they permitted no contact from the other direction, and used their (quite excellent) command of human language to deliver an ultimatum. The colony at Merovin was to be removed. Or they would remove it.

Thiswas a disturbance that promised real trouble. The central government might be involved. The companies scrambled to disentangle themselves, which compromised any defense that might have been made; and in the scramble, all in the hasty tumble of events that brought Cyteen kiting in with warships—some minor functionary whose head was on the block had stolen some microfiches and spilled the whole business to interested Cyteen officials. Other heads rolled—figuratively. And me government at Cyteen realized that the whole colonization effort was a monumental series of coverups that meant norecords could be trusted.

Now the colossus that was Union central government could move with amazing dispatch in crisis. Around this time Union's attention was on another discovery, in that period of prosperity just preceding the Mri/regul Wars. It wished to be rid of an embarrassment to prevent a souring of its relations with the Alliance. So it simply advised the sharrh that the colony was not authorized and resurrected the Gehenna Doctrine to assure the sharrh that if the sharrh wanted no contact, no contact would occur. End of statement. No sharrh to enter human space. No humans to enter sharrh space. They were dealing with xenophobes and an alien government with unknown parameters and exigen ties; and dis-contact was the operative word. Discontact; disengagement; dismantlement.

Human warships arrived with transports, stripped the space station, stripped the cities on world of all documents that might benefit the sharrh; and ordered the colonists to board shuttles for transport to human space.

Colonists rushed the spaceport, and with the first few loads, there was more difficulty restraining the boarders than coaxing them.

Then it came down to the colonists who had other ideas. Troops landed to scour them out. Cities were torched. Independent-minded colonists took to the hills and fired back.

That was the end of it. Union had another policy: not to spend the lives of its troops protecting people who shot at them. Union ordered its forces off world in 2655, pulled its ships out of that region, packed up and left, with a final word to the sharrh that humanity would accept a peaceful contact but would regard that contact henceforth as the sharrh's business—if the sharrh cared to make it.

Union effectively slammed the door on that corridor and went on about its affairs, carefully skirting the whole region thereafter, but not without listening in that direction. The sharrh were territorially smaller than Union. Union might win a war. But there was no percentage in fighting it. If there was one lesson Union had learned, it was that its component parts tended to erupt in internal disturbance whenever the central government was tied down to a prolonged problem in some other area; and Union simply avoided conflicts unless it was cornered or its authority was questioned. It chose to regard this incident not as a questioning of its authority but as a chance to chastise a few companies which had gotten beyond themselves. The blame went to them. And Union, the central body of the octopus that was Union, simply grew a little and controlled that corridor of access a bit more tightly.

Merovin's problems, alas, were only beginning.

Chronology

Note: Some dates are given for general reference and time frame; Merovin-pertinent dates are asterisked.

AD LOCAL EVENT

2600* Erosion of Gehenna Doctrine.

2608* Merovin colony lands.

2623 First Alliance/Union contact with majat of A Hyi II (Cerdin). Crew eaten.

2652* Sharrh demand removal of colony from

Merovin.

2653* Union/sharrh treaty cedes Merovin.

2654* Union troops remove colonists.

2655* Merovin exodus complete.

2657* The Scouring of Merovin.

2658* 1 AS Sharrh withdraw; elsewhere the first Gehennan to leave his world reaches Fargone.

2659* 2 AS Minor quake in Det Valley, Merovingen. 2672* 14 Calendree of Nev Hettek organizes Det

Valley militias: beginning of Re-Establishment.

2679* 21 Merovingen defies Nev Hettek.

2680* 22 Merovingen joined by other militias rejecting Nev Hettek rule.

2690* 32 Great Quake in Det Valley.

2691* 33 Flood in Merovingen.

2695* 37 Flood in Merovingen.

2698* 40 Flood in Merovingen.

2699* 41 Flood in Merovingen.

2700* 42 Flood in Merovingen; Angel of Merovingen found.

2701* 43 First contact of Alliance with the regul and the mri; dike breaks in Merovingen.

2702* 44 Flood in Merovingen.

2703 45 The Mri Wars begin: generally throughout this period, since the regul/mri assault came from a side of Alliance not involving Union, the Alliance fought alone. The Alliance, moreover, in its long distrust of Union, feared an attack on its flank from Union, The Alliance security organization (AlSec) founded 300 years previously by Signy Mallory proved all too powerful against the constitution framed by Damon Konstantin. Alliance became a police state on the home front, repressive and suspicious. Union, while worried, was not able to intervene across Alliance space until the war worsened.

2710* 52 Adventist riots on Merovin; Nev Hettek intervenes in Merovingen and the original Angel is lost.

2712* 54 The Angel of Merovingen is set on the bridge. Nev Hettek is expelled from Merovingen.

2720* 62 Merovingen's harbor destroyed in major quake; sea gates jam open; boats are sunk. Miraculously the Angel continues to stand. A sandbar forms above the wrecked boats, completing the devastation.

2721 * 63 The New Harbor is begun in Merovingen.

2722 64 Alliance government center removed to

Haven from Pell, to bring the government center closer to the war zone and improve reaction time. Pell is reduced to a regional capital, but remains the cultural, if not the administrative, center of the Alliance.

2724* 66 The Faisal Rebellion; ends Re-Establishment.

2730 72 Fall of Haven to the mri: Alliance finally appeals for Union help. The help is debated in the Union Council while Haven falls, and Union forces when they do arrive are met with distrust and anger by Alliance forces who do not understand what restraints have operated on the home front. It has been AlSec policy to keep the war out of the home territory at Pell; but there is now intense economic suffering and the loss of life can no longer be concealed.

2743 85 End of the Mri Wars: Haven retaken.

2748 90 Regul reach internal crisis because of hu man contact and go totally xenophobic.

2749 91 The Alliance suffers revolution as AlSec is curtailed and the Konstantin constitution is restored. Union observes prudent silence during this period.

2779* 121 Earthquake in the Chattalen. 2805* 147 Minor Det Valley quake. 2907* 249 Major flood in Merovingen.

3141 483 Massacre of the Meth-marens of the Hydri Stars.

3187 529 The Hanan break from the Alliance in a minor fracas limited to a narrow string of stars, but the struggle will last a thousand years. Union is not involved.

3241* 583 Altair Jones born on Merovin. 3243* 585 Minor quake in Merovingen. 3253* 595 Retribution Jones dies in flood.

Religions of Merovin

Sharrists

Sharrists believe that if humans can become more like the sharrh the sharrh will relent and let Merovin back into space. The sharrh, of course, are not supposed to be bothering the humans of this world at all, except that there are some of their number with piratical inclinations and no scruples whatsoever about using their worshipers.

It should be noted that the humans involved with the Sharrist cult range from denominations which have no religious aspects, to those which have very metaphysical beliefs that they can becomesharrh physically, or be reborn as sharrh, by becoming more and more like the sharrh.

Adventists

Adventists expect humanity to return with superior weapons and defeat the sharrh and take Merovin into the human community by force. Adventists have an aggressive outlook and are often involved in forbidden technology and plots. They give their children tech-names or star names; or names like Hope or Retribution. By this can be seen their philosophy. Those of mystical inclination hope to hasten the day of Advent by prayers and believe in a God of retribution. They do in general believe in karma, but view karma as a collective karma of all Merovans, which must be purified to enable the Retribution. A subcult, the Immaterial Adventists, often known as the Preachers, believe that the Retribution will be more metaphysical and look for human life to improve only after humans have acquired virtue enough to atone for their past sins of greed and corruption. Another subcult, the Sword of God, trains its members in martial arts and devotes its energies to gaining temporal power, obliterating sharrist influence, and preparing for war, and in the belief that God will subject the world to a second Scouring before the Retribution, and will reward only those humans who join in obliterating the sharrh all the way back to their world of origin. From these two subcults various other cults depend, each differing in some point of dogma; but these are the two extremes of Adventist thought.

Many governments have laws restricting Adventists, but they are officially recognized in Soghon and Nev Hettek.

Revenantists

This religion believes in reincarnation, that Merovin is a testing-place for souls or a place of punishment (denominations differ on this point) and that by virtue it is possible to win rebirth higher up the scale of society on Merovin and ultimately to another human world, in a long progress of karma acquired and ties to Merovin diminished.

Revenantism is the most formal of Merovan religions, and the most widespread. It is the majority religion of Merovingen and Canbera.

It has elaborate rituals and ceremonies, particularly revolving around birth, death, and majority.

Church of God

This cult claims to follow the old human ways of worship based on revelation and documents rescued from the Scouring. They are mostly a Wold entity, but maintain a religious seat at Gothhead and are strong among the Falkenaers. They are divided into numerous denominations. Most believe in an afterlife of all species, sharrh as well as humans.

New Worlders

This cult is an offshoot of the Church of God, which maintains that true belief has been lost and that God must be reapproached and rediscovered without reference to documents or cult objects. The New Worlders have three denominations: the Scholiasts, who believe this approach should be intellectual; the Ecstatics, who seek revelation; and the Revisionists, who try to apply both theories. They are predominant in Megar.

Janes

Followers of Althea Jane Morgoth, generally polytheists who practice magic and healing rituals. Jane Morgoth was a farmer from the Upper Ligur who convinced a large following of her powers and led the Ligurian Riots until she was arrested and executed in 432. Her followers be lieve she became a spirit of two sorts: healing for believers and retribution for nonbelievers. This belief was encouraged by the deaths of three of her judges in the same year; and it is said that no member of the jury lived beyond the decade. Detractors claimed that this was due to assassination by members of the cult, and in three cases by heart failure which may have been attributable to harassment.

Janes are predominant in the rural Liger but not unknown in Suttani and the Isles of Fire.

Seasons and Time

The concept of time on Merovin is based on twenty-seventh-century practice, which looks back to military timekeeping of old Earth, all of which was modified by the exigencies of the Scouring.

The result is a twenty-four-hour clock and a twelvemonth year.

The months are (from a numerical origin modified by history and agricultural practice): Prime; Deuce; Planting; Greening; Quartin; Qinnte; Sexte; Septe; Harvest; Falling; Turning; Fallow.

The months have twenty eight days, excepting Fallow, which has twenty nine, There is also the Day of the Turn, which serves as an intercalary unit to trim up the irregularity of the year. This daymay actually be more than one day in length; and is set by the Astronomer of Merovingen, decreed by the governor, and by all other governors. In practice however, it is well known in advance that such a decree will be made, so the event is virtually simultaneous despite the slow speed of communications, there being more than one Astronomer in the world. This Day is celebrated variously: Revenantists consider it a time of meditation; Adventists consider it a day without record, and no act without permanent consequence is forbidden: it is a carnival in Adventist cities. In Merovingen it is said among Adventists that the Angel sleeps on that one day; Revenantists call this heresy.

The weeks are a uniform seven days excepting the last week of Fallow, which has eight. The days of the week are Sunday; Monday; Tuesday; Wensday; Thursday; Friday; Satterday. The origins of the names are forgotten.

The days have twenty-four hours on the civic clock; but popularly (going back to the Scouring and the Restoration when time was reckoned without the benefit of precise clocks) the day consists approximately of hours between six or so in the morning and runs down to the eighteenth hour or so, until dark, after which a variety of regional time descriptions take over. A Merovingian speaking other than officially will describe the dark hours as Watches, of which there are six before the dawn—as, for instance, the top of the first watch is the beginning of full dark; the bottom of the fifth is a couple of hours before dawn; the bottom of the sixth is the first perception of sunrise.