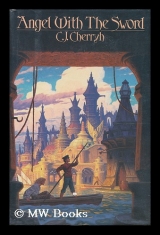

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

They looking for me? Lord.

She strained her eyes, arm clenched on the tiller, ready to swim about and try for the Splice, her other hand on the throttle, ready to throw it open wide and go roaring past the boat that kept the center-channel, between the two groups of pilings.

But someone was standing in that skip, an upright sil houette in the bow, a double glimmering of white in the starlight, one moving frantically. That was a flag-down. Someone waving.

Making a target of hisself, whoever.

That wake faltered, the engine cut back. She cut back her own, gathered her aching self up on her feet and strained her eyes into the dark as the gap narrowed. One skip was like most skips in the dark, in the bridge-shadow.

But that figure in the bow was gran Mintaka, one bit of white was her hair and the other a white rag that fluttered in her waving hand.

She waved back, tentatively. Her heart pounded against her ribs. What is this? What news?

They found 'im? Somebody found 'im? Is he alive?

"Jones," Mintaka's cracked voice hailed her.

She stopped the propeller, swung the bow to lose way, slewed till she had come to a crazed drift, and slowed the engine down to a low pop and thump. The other skip slowed and someone had a boathook out.

She got her own from the rack, leaving the steering to the other skip, let them meet her, them with several aboard. And it was not for the skip she had that hook.

"Jones," Mintaka said across the narrowing gap, her high voice cracking. "Jones—that young man—that young man o' yours—Moghi send word—"

She used the hook to grapple with after all, got to the side and hooked on as the hook took fromthe other side. It was Del wielding that hook, Del's skip; and the other with a hook was Mira. Beyond them was a stick-limbed shadow that came up to the side, and that was Tommy, Tommy from Moghi's.

"What word?" Altair shouted as Mintaka ran out of breath or good sense. "Where is he?"

"You got to talk to Moghi," Tommy blurted out. "Jones, he beat Ali—Ali was still talking when we left—"

"Figured we could stop you," Del said.

"Sword o' god," Mintaka said, her voice all a-wobble, her white hair wild in the wind. "Jones, that there was Sword o' God grabbed that nice boy—He wasn't running from no papa, that wasn't what he come running from, he told us a story, Jones—he's some kind o* foreigner—"

" Whereis he?" Sanity tottered. She appealed to Del. "Del, for the love o' God, where is he?"

"We dunno. We got a dozen boats gone down to harbor in the case they got that way, we got the word out east and west—"

"Thank God for that." She banged Del's pole with hers. "Hof, there. I got to get down there."

"Them crazies is who burned that bridge!" Mintaka cried. "Them damn fools trying to burn the town down, poisoning folks, cutting folks—"

Del got his pole clear. The boats began to drift. Altair flung the boathook end-down into the well and scrambled back to get the tiller.

Over by her, Del's engine came up quickly, the whole racket echoing off the walls of Wex and Spell man, shivering off the water.

Why? What's it to them what comes to me and mine?

It's what the Sword's done, that's what, it's burning that barge, it's gassing all them canalers, it's cutting old Wesh. Ain't nothing pushes the Trade, ain't nothing and no one pushes canalers without them pushing back.

Boats to the harbor! They got 'em stymied, they got 'em running.

But if the Sword was to know they was caught—

–What'd they do to him!

She shoved the throttle down hard, full-out.

There was a crowd of boats gathered at Moghi's, a jam-up of epic proportions. Altair cut the engine under the Fishmarket, steered up to the mass in front of Moghi's porch, there in Moghi's light, and bumped against the skips there. "Watch my boat!" Altair yelled at the nearest. " 'Scuse me!" She bounded off her bow into another well, handed her bow-rope to a man and kept going, onto the half-deck of another and down its length.

"Hoooo! Jones!" someone yelled. "That's Jones!" And: '"Here come Del and them!"

She traversed another skip and a poleboat at a run and clambered up Moghi's short ladder ahead of half a dozen curious.

"Moghi?" She hung in the doorway, in a gust of cold wind, facing a gathering of canalers in the main room; but their attention was all turned to inside. A scream came suddenly from the back, not a full-voiced scream but something uglier and hurt. " Moghi?"

Folk turned and stared her way, stared the other as Moghi showed up from inside, a grim, draggled Moghi in a blue shirt that had more than grime on it. He wiped his hands on a towel and it came away red. "Jones." With a nod back to the hallway behind.

"Moghi, I got no—"

A second nod. She went, and Moghi grabbed her arm, bringing her through and into the back willy nilly, back into lanternlight and stink and blood and something Ali-like tied to a chair. Five of Moghi's other men were there. One was Jep, with a cut on his temple and an ugly look on his whole face. "This damn traitor," Moghi said, and grabbed a handful of Airs curly hair. Ali yelped and bubbled blood out the nose and over his mouth. "You tell 'er, you tell 'er, damn you, what you just told."

"It's Megarys," Ali blubbered, "Megarys—ow!"

"Why?"

"Moghi, don't, don't, Moghi– owl"

"Had a feller or two to dispose of now and again—This damnfool done sold 'em, sold 'em off to Megary. Ain't throwed 'em in the harbor proper, no, this thief's been selling 'em, live and dead, right down the canal. Been taking them poor bridgefolk. Crazies. Been getting along right prosperous, ain't ye, Ali?"

"Ow!"

"That wasn't any Megarys broke in here!" Altair objected. "Who'd he let in here? Where from?"

"He dunno. He was just to wait for a heller to start up front and set this poison off to the upstairs, to get that man o' yours. Thatwas what. Only it didn't work that way. They come on through the front. It weren't nothing quiet. That smoke knocked himcold. And they come through and got your man. Ain't that so, Ali?"

"That's so, that's so—Moghi, I ain't never meant harm to the place, I was going to carry 'im out quiet-like. They was going to tell, Moghi! They was going to tell you what I done—"

"You damn dumb fool! I'd've broke your arm for what you done. Now I'm going to see you take a trip to harbor!"

"No, Moghi, no, Moghi!"

"Then you better talk, you better talk good."

"I told you, I told you it, they give me all this money, they told me they got to get this blond fellow, I figured it was some gang—I was supposed to carry 'im out back, just like he'd gone out—just let 'im disappear natural-like. They didn't tell me they was going to do the other, they didn't tell me the damn gas was going to smell up the place, they didn't tell me they was coming in after 'im and all—"

"Damn you," Altair yelled, "where'd they go? Where d'you meet these people?"

"Megary, Megary, Megary—"

"And the Sword of God," Moghi said, wiping his hand on his shirt. "The minute this fool heard you put that name to what got your man, he ain't had good sense. He was up to kill you. Out on that canal. Good job you tossed him out, damn good job."

"I never was!" Ali cried, "I never would've—"

"Would've what?" Jep grabbed himself a fistful of Ali's shirt. "Sell 'er? Sell 'er too? You damn sneak!"

"I ain't never, I ain't never! Jones, I never laid hand to you, I was going to help, I swear I was! I was going to make amends! Tell 'im, Jones!"

"Go for me with my own boathook, ye sherk! Ye deserve what ye got!"

"Don't let 'em kill me, Jones!"

She stepped back, gave a shiver.

"Jones! Jones, I go get 'im, I go find 'im, I buy 'im back!"

"You damnfool! They're Sword of God, you don't buy 'em!—Moghi, Moghi, Jobe's got some canalers gone to the harbor, and if things get too hot the Sword'll kill 'im. You know they will. They won't let him go. Without him to talk, they'll slide into this town like fish to water. We got to get 'im out before somebody gets to them."

"Your money ain't worth my men, Jones."

"They broke up your place, Moghi! What's the matter, you getting old, Moghi? You going to be an old man, let them crazies get a man out of here, let them bribe your help—!"

'' Damn your mouth, girl!''

"It ain't girl, Moghi!"

"It ain't old man, either! You're a damn fool, meddling with them cults! What you want? What you want me to do?"

They were shouting. The room was full outside. She clenched her fists and brought her voice down. "What I need is about six, seven fellows to go with me, go break into Megary, that's what we got to do, we got to get him outof there before they got time to panic."

There was a muttering in the room, a general melting-away of bystanders.

"What with?" Moghi said. "Have we got that smoke, huh? that's a damnfool move."

"Where's your guts?" She looked around the room, at men edging farther and farther back.

"Not me," one said. "I ain't half that fool."

"Moghi—"

"They ain't too enthusiastic," Moghi said. "They ain't fools. I ain't. We'll get 'em, we'll get 'em, but I ain't ordering no man of mine to go breaking into Megary. Jep?"

"I ain't too enthused either." Jep shifted his feet and scratched his neck. " Blacklegsdon't go in there."

" I'llgo," Ali cried. And: " Ow!" when Moghi hit him.

"We can block the harbor out," Moghi said. "Do this the smart way. Carlos, Pavel, you're going round to the harbor, maybe help them canalers. Maybe talk to old Chance on that riverboat. Done him a few favors, he'll talk to me."

"Dammit, that won't help him!"

"I'm telling you, Jones, you leave the thinking to them that has to do the bleeding! You want to go out there, they'll get them damn Megarys a nice pretty piece of merchandise if they don't blow your head right off. And then they'll sell you all the same, to them doctors. You'll end up on a slab up to the College, that you will! Or in some whorehouse up to Nex. You want that?"

"I'll take care of myself, dammit! I'll find someonethat's got the—"

"Me!" Ali yelled, "Jones! Jones! I swear I never do it again, I made a mistake, Jones, I'll go, I'll go, I swear I will, I'll make it good, Jones, I'll make it, swear on my mother, Jones, I swear, I swear, I swear!"

"I give ye Ali," Moghi said, with that sweet-nasty look in his deepset eyes. "Go with you right to Nex, he would."

"Dammit, Moghi, I'll take him, you give 'im to me, I'll take him!"

"You're crazy."

"I ain't crazy. I'm looking for a manin this damn hole! If he's all I got, he's what I'll take!"

"Damn you, Jones!"

"You said it, give him to me! If he can walk I'll take him."

"I c'n walk," Ali said, hoarse and bubbly. "Jones, I c'n walk, I c'n—"

"You want this trash," Moghi said, "you got 'im." Moghi drew his belt-knife and cut the cords, one, two, three.

"Ow!" Ali yelled: Moghi grabbed him by the hair and flung him out of the chair and face around again.

"If she don't get back," Moghi said, looking close into Ali's eyes, "you'll die for it. But you die slower. And I'll find ye, ye know I will."

"With my life," Ali said, a faint, bubbly voice, "with my life, I swear, Moghi, I swear on my—"

"Get!" Moghi flung him. Altair turned her back and stalked out of the hall and through again to the main room, with Ali shuffling and limping along at her back, all bubbly and snuffling. Canalers stared.

"Ye eavesdroppers," Altair called out around her, "ears in a body's business, any of ye want a piece of the Megarys?"

Eyes shifted the other way, shoulders turned. Del was there. He stared at her, his white-stubbled chin working. "I'll go," Del said.

"You got responsibilities," Altair said, and evaded the took in the old man's eyes. "C'mon, Ali."

She went out the door onto the porch—looked back at Ali shambling along after her holding his gut, saw a ring of staring faces around them both, canalers on the porch, out in the boats. "Megarys!" she yelled out. "It was Megarys helped them that done this! Anybody want to go over there in my boat? We got a man to get out of there!"

No one stood up and volunteered.

"Well, damn," she said, "Then some of you might at least get out there round West and here and there and clutter up them canals so they don't get a boat through."

"I'll do 'er," Mintaka Fahd cried out, waving her scarf. "Lord and Glory, I'll do 'er!"

"Who's this fellow?" That was old Jess Gray calling up from the middle of the boats. "Who's this they got?"

"Name's Mondragon!" Thatfor you, Boregy, and all your secrets. "He come to town to get away from them devils up in Nev Hettek. Megary's been trading with Nev Hettek and they got foreign help, it was Nev Hettek gold bought that poison, it was Nev Hettek and Megarys carried him off. You got no stake in him, but you damn well got one in what the Megarys done tonight!"

"You want them canals blocked, Jones, they get blocked!"

"Good!" She swung off the porch onto the ladder. Ali came down after, faltering on the rungs. She stepped down to the well of the Newell skip and Ali made it behind her, a grunt of pain and a stagger that rocked the boat. Newell kids squatted with mouths agape and eyes wide as she took her bloody shadow through the well.

Across that skip and onto Lewis's and the Delacroix. To her own, and Ali struggling and gasping to keep up with her. She heard another thumping across boat-wells, and a second, lighter, behind that. A man besides Ali landed in her well, all shadow against the light, a big man with a ragged coat.

"You got my help," he said, a voice half-familiar. She remembered the coat then, the cant of the battered hat.

Mary Gentry's man. Rahman Diaz. Mary who had lost the baby. Mary still had a son left, and her man came volunteering. Rahman scared her, scared her with the whole karma of it.

"Damn," she said. And another scrambling figure reached her deck, skinny-limbed shadow, spiky hair blowing in the wind, "who's that? Who's that? Tommy? Damn, get off of here."

"I come along," Tommy said in that high adolescent voice of his. "I ain't scared."

"Ain't scared!" She headed past her troop to the halfdeck. "Ain't scared! Damn! Rahman, get that rope free!"

Rahman moved for the bow-rope. Ali hunched his bent way up to the deck-edge and sank down there, arm on the deck, the other holding his gut. "Jones. Jones, I swear I never, Jones, I never had no heart for killing."

"Sure you didn't." She ran out the pole while Rahman got the boathook from his position in the well and Tommy dithered this way and that. "You going or staying?" she yelled at Tommy. "Get yourself back here off that bow, dammit, make ballast out of yourself, you c'n at least do that much—"

"Jones," Ali said, "Jones, that place is a maze, they got doors and doors—"

"You going to tell me that now?" She put the pole in, shoved past Del's skip. "Watch 'im, Mira—"

Mira lifted a forlorn hand and waved, that was all, And Mintaka Fahd waved her scarf. "Hooo," Mintaka hooted after her. "Hooo, there."

Hooo-oo, from a dozen mouths,

Mary Gentry's face she never tried to see.

"You got to go south," Ali stammered; it came out all liquid. "Jones, they don't use no big boat, it's Wharf Gate, they take their cargo out Wharf Gate—"

"Rahman, yey." She left the stroke to Rahman, swung the pole inboard and squatted down where she stood, toes tense on the deck. Her shadow fell on Ali's face, Moghi's lights falling behind them. "You want to talk truth, you damn flesh-peddler? Where?"

"It's truth, it's truth, Wharf Gate. They take 'em all that way."

"You damn sneak. How d'I believe ye?"

"I ain't lying. I ain't, Jones, I swear to you. Wharf Gate. They got these riverrunners, they come right up by the Dead Wharf, I heard 'em talk. Jones, Moghi give me this poor old sod to throw in harbor—he come to, he begged me, he begged me, Jones, he didn't want to go in that water. I ain't no killer. I sold 'im. That was the first. Ain't they better off? Ain't they? They wantedit, Jones, they wanted it—I ain't never thrown nobody in harbor. Megarys don't kill 'em. They just—"

"—sell 'em. You got the morals of a sherk, Ali! How much you get for a body, huh?"

"They was going to tell! They was going to tell if I didn't do it this time—Jones, it wasn't supposed to go this way—"

"I'll bet it wasn't." She stood up, caught sight of Tommy's pale, round-eyed face.

Accomplice? Or innocent?

She ran the pole in, took up the stroke. "We're going over to Megary. First. Look it over. Know what we're dealing with."

"Jones!" Ali protested.

"You shut it down."

Rahman just made his stroke and never said a word.

Chapter 9

IT was easy work, moving the skip with Rahman on the other pole. No panic now, just the rhythmic move of water, the same as any night-time trip through Merovingen-below. Altair took her strokes sure and quiet, letting Rahman do most of the real push.

Man ain't been t' one end of town and the other tonight. Lord, how much time have we got? Just after dark when I was with Jobe; past midnight getting back from Boregy, damn his guts.

We got, what, three, four hours to dawn. Shy side of two hours before the tide clears boat-draft at those gates.

Ifthey're going to leave town tonight.

They got to. Too damn many people looking for Mondragon– Sword'll get wind of that gathering over by Moghi's—they'll sure know when them canals get blocked and they try to get anywhere. And what's Megary doing with all of this? Megarys has got to be scared, is what. Megarys bought themselves trouble, got their arm twisted right good with their foreign friends—

Sword's running this. Nobody else. I got to get him loose, I got to be ready when the Trade gets those canals blocked. Got to be ready to do something, got to have it figured.

Got to get him out of there before they know they're trapped.

–Got to get 'im out of Merovingen.

Find him some ship, out to sea.

Get him out of here. For good.

Never see 'im again.

What else can I do?

She shoved hard, til her arms hurt more and her gut hurt less.

Damnfool, Jones. Tomorrow ain't in reach, is it? Ain't nothing good there, is there?

So stop thinking on it.

Mama, mama, you gone away tonight? I don't blame you. This is a proper mess I made. No wonder you ain't too proud of me.

The way bent to Old Grand, and shadow closed darker still beneath the maze of bridges that roofed the Old Harbor's onetime thoroughfare.

Boats were moving, somewhere at their backs. Those skips and poleboats tied up here were few and far between, mere shadows along the edges of buildings. Old folk. The disinterested. The isolate.

Those so far into the dark ways that they had no part or traffic with honest canalers.

Those same honest canalers back at Moghi's were making haste as fast as canalers were apt to, and trying to sort out just where what boat was going: she could figure how long that would take. And the canals and those sea-gates would get blocked. In about an hour or so, when enough of them got organized and got into position. When they had talked enough hardheaded water-rats never atMoghi's into going along with a jam-up around Megary, and settled who was going to block those places where there was likely to be shooting.

More talk and more delay.

"Cut over to Factory," she said to Rahman, and swung the bow over for that turn. The eddy of the Old Grand jog was shoving at the skip; wind hit in a gust. It slewed, but practice borrowed the slew into the turn, her pole down for the moment it took, Rahman picked up the push again with never a word, not a piece of advice since he had come aboard.

Rahman never did talk. He never did talk all those years ago when I brought his and Mary's baby up from Det-bottom, when he come up from hunting that bottom empty-handed.

He knew, that's what, he knew that baby was gone, even when it was still alive. Mama knew and he knew, him standing there and never saying thank-you. He don't talk now. What's he know that I don't?

Lord, he's Revenantist. I put karma on 'im, didn't I, bringing that baby up alive. I laid karma on that dead baby's soul, on all of 'em, Rahman and Mary and Javi, and Rahman ain't having me get killed without he clears that debt, he's got to save all their souls from what I done saving that baby, or they can't never get free of this world till they and me all get born together again and they pay me off. He's thinking on his next life, that's what he's doing, Lord and my Ancestors, I got a suicide on my hands.

Tommy—he's just plain fool, coming out here, whatever brought him. And I knowwhy I got Ali.

A suicide, a fool, and a damn traitor.

They passed Mendez Isle and Fife, where vermin scampered along the narrow ledges and squeaked and squealed at a passing skip. A cat eeled round a starlit corner of Mendez, shadow as much as its intended victims.

"Hey, we got a marker up there," she breathed, spotting the standing pole at Ulger's crumbling corner. "Hin."

"Yey," Rahman agreed. "Ware hook," The bow swung under his strong push.

"Ware afore." She swung the pole into me well past Ali's head and squatted where she stood, let her bookman cross past her to grapple the tie-up nearest that marker. She read that aged pole where she squatted, peering through the dark at the rope-banding on the pole while she made the jury tie to hold them at the ring. "Damn place," she said, seeing how the topmost rope was rotted and gait-crusted. "Level's changed here and they ain't fixed this thing in a ten-year."

"Running in fast," Rahman said. "Tide'll go high, we got that seawind."

"Smugglers is bound to be wise to that too," she said, and sat there and gnawed her knuckle. The wind gusted. then something boomed, boomed and rumbled with authority. Explosion? It seemed a trick of the wind for the moment. Then she took that instinctive look skyward all the same, and it rumbled out again. "O God, that's thunder."

"Sounds like something'sblowing in," Rahman said, crouched by her.

Nothing showed yet. The stars were still clear above the black hulks of Tidewater isles. Her mind built sea-storm, black wall rolling in, pregnant with lightnings, the way such storms came. Calm before it, and the winds—the winds—

Thunder rumbled again, distant and not distant enough.

"They'll hear that. Lord, that boat coming in—they'll have their eye to that, they'll move in early—"

"Or pull out."

"I ain't betting on it. O Lord, it's usgot the trouble, we got that sea coming in and they ain't organized back at Moghi's yet—I knowthey ain't—"

"They hear the thunder," Tommy said, "they hear it, Jones."

"So do the damn slavers! They'll go early, go while it's still dark. Lord knows who else is moving—We got to go, we got no time to wait around."

Rahman grunted, shrugged his big shoulders and spat off the deck. "Yey."

Karma.

Suicide. Thunder rumbled again.

"Dammit—" Her focus shortened to the dark, curly-headed lump huddled there in front of her. She shifted the pole in her hands and nudged him so that he looked up at her. "Ali. How d'they go out? Megary Cut?"

"I don't know."

She nudged him hard. "Ali, I thought you was going to be more helpful than that."

"I ain't lying!"

"Well, you ain't helping, either."

"There's this landing south. By the Cut."

"I know it."

"An old freight door, little slip there." Ali's breath hissed and faltered. Wind rattled a board somewhere. "I

run Moghi's boat right up there on the slip. I knock at that door. They come out and they take—take the delivery."

" Thathow it works."

"Jones." He shifted up, leaned on the deck-rim. "My God, Jones, you ain't getting in that way, you can'tget in, they'll kill us."

"They won't kill us. They'll sell us right up the river, won't they? Rahman, I got some things to ask our friend here. You want to top off that tank? I got a full can down in the well."

"I'll help," Tommy said, a whisper too close to voice.

"Keep it down," Altair said. "You got to learn to keep that voice down—" Retribution had said it to her in these same tidewater canals, taught her to pitch down, snapped her on the ear when she forgot—

–Taught me the dark ways, mama. I thought ever'one knew 'em.

"Now, Ali," she said in her softest, lowest voice. Wind sighed down the canal, stirred her hair at the front of her cap. "I killed folk before this, Ali. That's truth. It don't scare me. Just in case you think of shouting out." Quiet movement in the well to their left, where Rahman found the fuel can. He set it on the deck and came up after it, cat-footed, big as he was. "Ali," she said. "You hear me? You hear me good?"

"I hear you," Ali said. He leaned his forehead on the deck, one arm tucked across his gut. "Jones, Wharf gate, I swear on my mother it's Wharf Gate, I ain't lying, we can't go into that place, they got doors and bars—"

"You been in there, huh?"

The whites of Ali's eyes shone as he looked up. "I never."

"Lie, Ali. You wasn't going to lie to me. Your mama's gathering a lot of karma, ain't she?"

"Once, Once, I was inside."

"Deeper and deeper, ain't ye? Selling bridge-folk—"

"In the winter, in the winter—Jones, they lie there freezing, Megarys give 'em food, they got a warm bed—"

"Just like my partner."

"That was different!"

"I tell you, Ali, you remember that little scene back to Moghi's porch. Now, it takes a lot to get the Trade stirred up, but they're stirred. And there you stood up in public with me when I said it, about the Megarys. You know what that makes you?"

"A dead man."

"About three different ways. Me or Moghi or them Megarys. Or 'bout any canaler in town. Lot of folks ain't too fond of you right now."

"I ain't never lied to you!"

"You got a way to buy out with me. MaybeI could put it right with Moghi. You understand me? You know what those Megarys'd give ye? Ye know that, Ali?"

"I know." His breath came through chattering teeth. "But I don't know the rest. I swear I don't know, I never done that end."

"You know what I want you to do for me, Ali?"

"O God, Jones. I can't. I won't."

"You c'n lie real good, Ali. I know ye can." Fuel-smell wafted to her. She heard Rahman and Tommy quiet at their work, liquid gurgling and thumping its way into the tank. "Rahman. Save some of that back. I got this bottle down in the number-five. You want to fill that thing for me? Stick an old rag in it."

"You got matches?" Rahman asked, matter of fact.

"Plenty."

"Jones," Ali said, half a whisper. "What'ye think you're doing?"

"Just something my mama taught me."

"What's she mean?" Tommy asked. "What's she mean?" But no one answered him. Rahman went down on one knee, got the bottle and the rag.

More fuel-smell, carried away on the fickle wind.

"Got two bottles," Rahman said.

"That ain't too many." She sat there and chewed thoughtfully at a callus-shred.

You sure he's in there, Jones? No, you ain't. You ain't dealing with the Megarys, you know it. Sword of God—

Sword is rich folk.

City's Revenantist. And what else could get foreigners in and out of the city as well as them Megary boats?

Lord, they got the law bought, they trade corpses to the doctors up at the College, nobody ever questions 'em, ain't no way them boats get searched.

Lord, questions, Boregy said. They want to ask him questions. What are they doing to him?

"Where do they keep 'em?" she asked Ali. "Top floor or bottom?"

"Bottom. I think it's bottom."

Damn, all barred. Ain't no way to break in there; they'll have took real good care so's no one could break out.

Lord and Glory. So no one could break out. Who else in town don't ever have to worry about burglars breaking in?

"How's that bottom floor? How's it set?"

"They got—" Ali traced a design on the deck at the side of her foot, trembling finger moving on worn paint. "Got the hall I seen. South door. You go in. You got these hallways left and right and these stairs—"

"Where do they go?"

"I don't know, up—up. They got some kind of warehouse, I think they got this big place over here they put the regular stuff, the legal stuff; that's here. All above, I dunno, Megarys live up there. Maybe they got other things, I don't know. They just got two stories."

"You going to do me that favor?"

"Jones—" Ali's teeth fairly chattered. "I hurt, dammit. I can't—"

"Hey, you're still alive, ain't ye? You ain't at harbor-bottom. It don't hurt a bit down in Old Det's gut. You want I tell Moghi you went back on me?"

"No." They did chatter. "No."

"You going to do it for me?"

"I—All right, all right–"

"Rahman. Let's move 'er up a bit, you ready?"

"Yey," he agreed. The fuel was capped up. Loose stuff was stowed. Rahman squatted resting on the deck and Tommy had gotten down to the well. Rahman got to his feet as she slipped the tie and stood up with the pole.

She pushed gently off the ledge. Rahman pushed from his side and the skip moved along smoothly under way, off Ulger's comer and back to Factory's narrow center.

Calder and Ulger's length inched past, dimly starlit. Bridges were rarer in the Tidewater. Most of the isles were two-storey now, their old first-floors filled and mostly sunken. Calder had no ledge at all, just a balcony round the upstairs, and the last bridge off Ulger showed as a decrepit low span that hardly admitted a skip with the poler standing.

Rahman grunted, having seen it too.

"Little port there," she said to Rahman as they headed under. "Hin. Hin cinte."

"Yey." He nudged the boat to the high center of the bridge and dodged a hanging board with small headroom to spare. No pilings. It was a jury-bridge between two second-storey doorways, abandoned as flood and rot took Calder's canalside.

"Damn, city ought to take that thing." Her head was clear, quite clear. She smelled fuel-stink, very faint over the canal-smell. "Where you got them bottles?"

"Number five."

"Port, ya-hin."

Factory jogged, bent toward broad West; the boat edged northerly with the push off West Canal. A solitary, rag-canopied skip occupied the jog. A waft of bad air came down the wind as they passed.

Muggin. O Lord, it's Old Man Muggin—Lord, Angel, keep him sleeping.

What does he doto keep that damn skip running?

Megarys? He couldn't. Old fool don't have the wit left. Couldn't catch them bridgefolk.

"Muggin, ne," Rahman breathed.

"Yey," she whispered. "Starb'd, hin."

The bow swung gently. Wind hit them as they entered West Canal and she cast a look up, blinked in dismay at the shadow in the black, a third of the way up the sky, No stars, just that gold-through-smoke flicker of lightnings. She shortened her glance down to Megary Isle, to a barren, scant-windowed face of aged brick and board. They were exposed now, under those grim barred windows. But they were just a skip on its business. A skip with no more aboard than might be family, ordinary traffic passing in this night—they might well be the only ordinary-looking thing on the canal, boats being scarce in the Tidewater tonight.