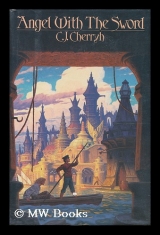

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Chapter 8

THE engine-sound echoed off the walls of the Signeury, those big blank walls that showed nothing but rifle-slits to the outside, and had precious few bridges for all its great bulk. Stone was under its foundations; it was all of stone itself, and while Merovingen-above glittered with its night-lights, while the high houses had their windows shining into the night and casting their reflections down into Merovingen-below, the Signeury crouched like a baneful giant in the dark water of the Grand, turning engine-sound into hollow thunder. No boats sheltered under Signeury Cross: it was prohibited. Nothinglurked about those bridges but the law themselves. Altair hugged the tiller under her arm, kneeling on the deck, and took the throttle down, letting the skip glide for Golden Bridge and Boregy. There was plenty of way on her, no need of the pole, here where the Grand itself went treacherous with Greve-current and none so far upcanal they had to sink great slabs of upriver stone to keep the bottom from washing. It was strange territory, uptown; it was all blank walls and high, suspicious Isles without the under-the-bridges conglomeration of shops and manufactories that was canalside life belowtown.

Boregy hove up beyond the dark web of the Golden, dark as the Signeury, merest shadow excepting a light or two in its uppermost levels. Its sides were deserted, It hadno tie-rings, being the Signeury's neighbor. It had one of the Signeury's bridges going to it alone; and by its balconies was the walk eastern hightowners had to take to council and to the Signeury: thatwas influence. That was the kind of place Boregy was.

But it got attacked, and people got killed; and the governor just arrested Gallandry, who was one of the victims.

O Lordand my Ancestors, I got to go inside this place, I got to make 'em help—

She wobbled to her feet, cut the motor and used the pole the last few feet, fending off a drift into Boregy's wall with a jolt that near took her off the deck. The pole shed a splinter into her palm with a faint far pain somewhere lost in the buzzing of her brain, the throbbing of a headache. She saw the gardeporte, a grim little pierced tile with a devil-face that was Boregy's canalside window. A bell-pole dangled a cord there in the reach of a skip deck. She maneuvered up to it and pulled.

A bell tinkled inside, a tiny sound against the water slap in the wide Grand.

She pulled the cord again, and the gardeporte rattled. The devil's mouth and eyes flared and shadowed as a human face looked out behind it.

"Who?" a gruff voice asked through the devil-mouth, a voice like thunder itself—Boregy's gate-warder, called from whatever occupied him. "Who are you?"

"Name's Jones. I got to talk with the Boregy."

"You say. Go to hell. Honest business can wait till morning." The face withdrew, the devil's eyes flared gold lamplight and went out as the port thunked shut.

"Dammit!" She grabbed the cord again and jangled it over and over. The devil-face fleered light and the man reappeared behind its grimace.

"You want I call the law?"

"Mondragon," she said. " Mondragon!" And her knees shook when she had said it. She felt sick inside. Forget my name, he had said. I was crazy out there.

"What's your name?"

"It's Jones."

"You alone on that boat?"

"I'm alone."

"Pull into the Cut, up to the door."

Thunk. The tile shut again. The devil-face returned to dark. She drifted a moment away from the wall, then moved her aching arms and put the pole in again, pushing toward the solid iron gate,

Now's done it. Now you got yourself uptowner trouble, Jones. They know your name and his together. Was that smart at all?

But, Mama, Angel, I got to go there. I ain't got nowhere else.

Have I?

She turned the skip. The pole grated on stone below the water, the bow slewed about and bumped the iron gates. Chain took up suddenly, hand-cranked gears rattled and clanked as the big valves grated, groaning their way apart enough to admit a skip. She drove on the pole. Nothing but black lay beyond those jaws.

Retribution's ghost perched on the bow, mending a bit of rope. Looked up at her, all dimly sunlit in the dark.

The ghost said not a thing. It was just company.

You was always into things, mama. You never let nobody near me. Never let none of your dealings touch me. Never knew how that was. Never knew why we didn't have no friends and I had to be a boy.

Dammit, mama, you could've said why that was. Now you come back. Nowyou got no advice either.

You were a kid, the ghost said finally. What could you tell a kid?

Tears stung her eyes. She poled blind in the dark. The chains rattled behind her and the doors slowly clanked shut, cutting off the wholesome breeze. For a breath or two there was total dark and she glided.

Damn place, Altair, damnfool stunt, you're going to smack into a wall or a step—slow 'er down.

The ghost was gone. The dark was complete. Then light burst in a rectangle of an opening door, and scattered on the black water and the buff stone of the Cut walls.

She poled over to the porch-landing and blinked into the lamplight. The open door was invitation—from a place that had lately suffered murder and invasion.

Fool to go in there. Fool to come this far, Altair.

She bumped into the landing and caught a tie-ring with her bare hands, letting the pole-end fall in the well and the rest lie aslant across the deck-rim. Muscles strained, the way of the boat fighting back; sore joints protested. She braced bare feet, snatched the rope through and made fast.

Then she stepped across to that stone porch, climbed the single step and walked into the lighted stone hall.

The door swung to, kicked from behind it. She spun and staggered to a quick freeze, facing a man with a knife, as another door crashed open and poured armed men into the hall at her other side.

It was a climb up back stairs and into dim places, with men in front of her and behind. They had not taken her hook and her knife; and they had kept their hands off her, but they had their own weapons, and those were out, bare steel.

Up two turns of that inside stairs, with an electric here and there—she did not gawk; she had no mind for anything but the man in front of her and the men behind her and the haste in which they moved her along.

Then they opened a door onto a red stone hall that left her standing numb, mouth open until she realized it and shut it on a gulp of air,

Lord and my Ancestors.

Polished stone, white-veined red; columns, statues out of white and black stone. Light agleam as bright as day– the white light of electric, in a gold-and-glass lamp that broke up light and threw it everywhere. They had to shove her to get her moving again; and the cold red stone of the floor was like silk under her wounded feet.

More climbing, up a staircase wide as Moghi's whole front room. It dwarfed all her imaginations.

Money—O Lord, money enough to buy lives and souls. Money enough to drink down all the troubles in the world. Gallandry was nothingto this! O Mondragon, I see why ye backed up from me on that boat, belonging here. O Lord and Glory!

A great gilt table crowned the summit; a man in a blue and gilt bathrobe stood by it, a black-haired man with a fierce down-turning mustache and black eyes that burned her to ash even before she had climbed the last steps.

Get this man out of his bed, make 'em light all these electrics—This is a man don't talk to no canalrats, this man looks at me like something dead and floating—O Lord, I got to watch my mouth with this one, I got to talk uptown talk, make this m'ser believe I know Mondragon for sure or they'll take me downstairs and beat me. Is that The Boregy hisself, and him that young? No. Can'tbe. Boregy's old, ain't he? Got to be some son of his. I got to argue with himfirst and then Boregy.

O Lord, I'm all sweated, and them with all them baths.

She stopped and jerked her hat off and clutched it in both hands, there in front of this m'ser who was probably straight from his bed, whatever he was doing there, this m'ser with all these armed men standing around him.

"You mentioned a name," the Boregy said.

"Yessir," she murmured. If he was not going to say that name outright here, she reckoned she ought not to. She looked straight in those black eyes and felt like she was going underwater. Down in the dark of old Det.

"Well?"

"He's got trouble. I got to say its name?"

"You know its name?"

"They got 'im. they broke in where he was sleeping and they took 'im—I don't know where. You got to help. He said you was friends. He said—he had to get here. Now he can't. They got him."

"Who areyou?"

"Jones, ser, Altair Jones. You c'n ask anyone" No, fool. This man don't talkto the likes of us, this man don't ask his own questions.

'Cept now.

"It must be the girl from Gallandry," a man muttered.

"So he did get off that barge," the Boregy said.

"He got off," Altair said. "We jumped, him and me."

"Did you take him to your friends?"

"Only thing I could do—" O Lord, no, that ain't what he means, OLord, see his eyes, he's thinking about his basement right now. "Damn, I ain't turned him over to them, no, I didn't!"

The Boregy went on staring. Her knees went to jelly.

It's the basement, it's the basement sure. O Lord, save a fool! What do I say, do I tell him we was lovers, do I say anything at all until he wants to talk to me?

"Where is he now?" the Boregy asked.

"I dunno, I dunno where he is, I come to you to ask where they'd go."

"To me?"

"He give me your name. You got to go to the governor, get the law, get the hightown go find him—They didn't kill him, there wasn't any blood, it ain't killing him they want—not yet. You got to do something."

The Boregy stared and stared. Finally he moved his hand. "Chair," he said; and one of the men ran to the side of the hall where a chair was. Boregy turned the one already there, a great wooden chair at the table-end; and sat down, staring up at her. "Sit down," he said when the chair arrived, a spindly gilt thing with white and brown cloth. The man set it down across the angle of the table-corner. "Sit," Boregy said.

"My pants is dirty." It came out all strangled. Heat rushed to her face.

"Sit down anyway."

She sat.

"Wine." He made another gesture aside. "Where was this? What happened?"

"I put him up to Moghi's. This tavern, down on Ventani-bottom. 'Neath Fishmarket Stair. I went for my boat, friend had 'er, I come back and some damn—Somebody broke in there—" Her teeth started to chatter and her eyes to water, and she drew a great breath and fought bom tendencies down. She spread her hands to cover the interval. Her palms were blistered, calluses and all. "They flung this smoke stuff. Knocked out the whole d—whole tavern. They got him that way."

"Pathati."

She blinked stupidly.

"Pathati. Gas. It's a sharrist weapon."

'' Sharrist.''The whole world tumbled in and reason fell after it. "O Lord, what's sharrh to do with it?"

Boregy did not answer. A man brought the wine up, red wine in a bottle all of cut glass; and stem-glasses the same. The man set it down and poured, gave Boregy one glass and set the other beside her on the big table. She picked it up and her hand shook. She used both to get it steady, and drank a sip.

"The law," Boregy said, "is not an option in this matter."

She blinked at him, helpless.

"The police will not be interested," Boregy said.

"They flung him off the bridge."

"What?"

"The law flung him off Fishmarket Bridge. I pulled him out." Her teeth wanted to chatter again. There was an ache in her gut, in her bones, in her skull behind the eyes. "I figured maybe—maybe you got friends could put the shove on the law on the other side, that's why I come here, I mean, someone's bribed 'em against him, a bribe from the other side'll work forhim. Won't it?"

"You don't appreciate the difficulty.

"I don't." The words muddled up, made no sense. It sounded like no. She held the glass in both hands to keep it from shaking. She made a shift of her eyes about the room, where a half dozen men stood waiting on a Boregy and a canalrat to drink their wine. She made that look a gesture. "You got them, don't you?" Landsmen that they were, they looked dangerous. They looked more dangerous than the law ever looked. "If you know where they went—Lord, we got to do something, they gothim, they could be doing anything—"

"They might well." Boregy turned his glass on the tabletop, fingers long and white and slender. He shot a glance up at her. "You have to understand the inconvenience. Your coming here is an embarrassment, one we can ill afford. You weren't in a position to understand that, perhaps. But if the police did, as you say, throw him off the bridge, that does indicate the governor's official posi tion, doesn't it? Or someone's opinion—very high and influential. It's virtually the same."

" Lord, them blacklegs'll sell for a penny!"

"Not in this case. No. Nor for coin. It takes a different currency. Neither of us has it. Your coming here is inconvenient, to say the least."

"You're his friends!"

"We were his family's friends." The glass made another revolution and Boregy never looked down to see what his hands did. "That family no longer exists. Presently he's a hazard. Consider Gallandry's fortunes, if you doubt it. Mondragon's a contagion."

She set the wine down, shoved the chair back and started to get up, hat in hand. A man stepped up and shoved her down and shoved the chair forward.

"Damn you!" Her yell echoed round the hall. A heavy hand descended onto her shoulder and men moved uneasily where they stood. Her knife occurred to her. Draw and she was dead. She understood that. She glared at Boregy, and Boregy waved his man off. The weight left her shoulder.

"Your loyalty does you credit," he said. "You've done as much for him as a girl could. I don't say I don't appreciate that quality—you don't have to be afraid of us. I could use a resourceful employee. What are you—a poleboater? You'd be in Boregy service, have a place for the rest of your life, a very well-paid place."

"I'm a skip freighter," she muttered. "And I'll come back later if ye want me, and I won't say I was here if you want, but I got to go, I got to find him if you won't say where they'd've took him—You could tell me that! You could give me that much!"

Boregy stared at her with that black gaze of his and never blinked. "Why are you so interested?"

"'Cause he ain't got no damn help from you!"

"Drink your wine."

"I ain't drinking any wine, Let me out of here!"

"Jones, your name is. Do you have a first name?"

"Altair." Lord, now her mouth was going to go weak, her chin was going to tremble like a baby's. O Lord, I

could kill this man. I could kill him, and then they'd kill me, if they ain't going to do it already—

"I'm Vega Boregy." He folded his white hands in front of him on the table. "So we have something in common. You'll understand when I say our influence is limited in this. I have a cousin and two of my men dead yesterday. The Sword has reached into this hall: that'swhy Gallandry was arrested and we were not—the governor has that for evidence that we are victims and not perpetrators. We dare not speak for Gallandry. Are you understanding me? As Adventists, we cannot afford a tie to the Mondragons, except a historical one. Your friend is an irritance, a dangerous inconvenience."

"He trusted you!"

"That he might have, had he come quietly. But someone betrayed him. Someone he trusted, surely. Fear, you understand. They set the law on his track and that led his enemies to him—by extension, to all his possible allies. Don'timagine that the Sword doesn't extend even into the militia. Or that sharristinfluence might not extend to Merovingen. Do you see what you've involved yourself in?"

"I don't see. I don't understand. I don't want to see. Let me out of here and I won't say a thing."

"Do you intend to go searching for him?"

"I ain't saying what I'll do."

"What canyou do?"

"I got my knife."

"Your knife! Do you know what the Sword of God is?"

"I know as much as any honest canaler knows, which is that I don't want nothing to do with 'em. But I ain't going to quit. You sleep good, m'ser, you sleep real good, and just let me go do what I got to do and I ain't going to repeat to no other soul what you told me."

"Girl, you're a fool."

"I am. I been one for days. But I ain't going to leave him to 'em."

"You know he's from Nev Hettek."

"I never knew that proper, but that was high on my guesses."

"The governor of Nev Hettek is a man named Karl Fon. Do you know Fon is in the Sword?"

Her heart lurched a few painful thumps harder than it had been."I heard that rumor."

"The Mondragons were ordinary Adventists, like most of Nev Hettek. An old, well-placed household. Thomas– the youngest son—was drawn into the Sword. Does that shock you?"

"He told me he was, once. He said he quit them."

"What more did he say?"

She shook her head.

"That's important, you see. Whyhe quit them. And how far he was in on their councils. He was Fon's close friend: he was in very high councils in Nev Hettek, above even his father's access to those levels. Perhaps Mondragon learned more than he wanted to know. But whatever involvement he had with them—terminated. The whole family was killed. Except Thomas Mondragon. He was put up on trial as a sharrist saboteur."

"He ain't!"

"That was the standard accusation—for any enemy of the governor. He was sentenced to death. His execution was set three times and three times postponed. Then he escaped, escaped the governor's own residence, so the rumor came down the river. With everything he knows. Do you see why our own governor might urge him to get out of Merovingen? He's trouble. He's truth on two feet. He knows things our governor doesn't—officially—ever want to know about Nev Hettek's internal workings. The word is war, girl. War against wicked Nev Hettek and its apostate governor—if certain forces in the Signeury can get public confirmation of the things Thomas Mondragon knows. They'dwant him too. The sharrists assuredly want him: he knows intimate details about Sword of God operations and tactics against them. The police here would question him if they dared know the answers officially. The Sword absolutely wants him back: they'reagents of Karl Fon. And if the Priest of the College finds out what they've got within their reach, and they get their hands on him, the Revenantists will want to extract a public confes sion from him before they hang him. While our governor– the governor just wants him out of town before Nev Hettek becomes convinced Merovingen has the wherewithal to stir up a war. He's old and he has the succession to worry about and this is the kind of thing that could create—great difficulty with the heirs. Shifts in power. The Sword has been here for years; and that fact is known in very high places. So are the sharrists active here—but that's not a thing you'd better breathe even to yourself, young woman."

"Was it sharriststhat got him? This pathat—patha—"

" Allthe terrorists borrow from each other. Sword uses pathati. So do the sharrists and the Janes. That tells you nothing. It was likeliest the Sword. But I don't rule the other out. I don't rule it out even if they declared what they were. The factions lie. It's their great weapon. They blame their actions on each other. And Mondragon knows what all those lies are. He's been inside their most intimate councils."

"But—But you got these men—" She passed a gesture round them, at the armed guards. "Man, they killed your cousin, they broke into your house, ain't you anxious to do nothing—"

"Don't you see past the moment? Boregy can'tact. We could start that war. We could touch it all off—and your friend Mondragon will still end up with his head in a noose—at best. No matter which faction gets hold of him. And some are worse. I'd rather not have any of my house standing with him in the Justiciary."

"Well, I ain't gotnobody, I ain't got nothing in my way. You damn well let me out of here, you let me go, I'll find them sons of damnation, I'll have their damn guts out—" It was yell or cry. She shoved the chair back but the man behind her stopped it with a grip on the back of it. "Damn you all."

"Girl. What's your name again?"

"Jones. It's Jones, damn your heart to hell. You ain't no use, you ain't nothing, you can damn well let me go, it don't cost you nothing."

"But it could cost me a great deal, sera. It could cost us everything." He stood up, stood looking down at her trapped there against the table, reached down and lifted her chin with his hand.

Spit at him. Lord, they'd gut me. Here and now.

"But you don't think in those terms, do you? You don't understand a thing I'm saying."

4'What's it to me?"

"What's a war more or less? Maybe nothing to you. Maybe it makes no difference to you. I assure you it does to me. How much time have they had?"

"Maybe—maybe an hour, hour and a half—" Her chin trembled in his hand. He let her go. She clenched her fists and ground her cap to shapelessness in her hands. "Why?"

"I can't tell you where he is. I can make two guesses. One is the riverboat out there in the harbor: it brought him here and it might well take him out again. They might have taken him straight aboard. It's also possible they didn't—since that ship is the first place any opposition might look, and opposition is more than a possibility, once this news spreads. I'd place my bet they haven't gone at once and they won't use so conspicuous a boat. Something less evident, a fishing-boat, a coaster. There are sea-gates all along the Old Dike. That'sthe quarter I'd bet on. They'll have to find their boat, get their prisoner to it—"

"Then they can't've moved 'im out yet! Ye don't move nothing by them gates at ebb. Ye got four deces difference in them Tidewater canals, high tide to low—"

"There's another reason, however unpleasant to contemplate. They'll have questions to ask. We're not talking about the gangs, understand. We're talking about an organization that penetrates into the Signeury, one that knows he's been here long enough to expose certain of them if he chose to do it. Certain people might be very interested in discovering all his contacts here. Their safety is at stake and Karl Fon's orders may well take second place to their own concerns. They'll want a place and a time to question him on their own behalf, a place close to the harbor, a place where neighbors don't call the police."

"That's the whole damn Tidewater!"

"So I understand." Boregy made a motion to his men. "She'll be leaving."

Altair shoved the chair back, and this time it moved. She levered herself up and got her knees locked.

"I'm sending you, you understand. That's the help I can provide. I personally advise you take what you know and what I've told you and say nothing and do nothing. But I doubt you'll regard that. Do you want food? Money?"

She shook her head. "I got to go, is all." Lord, he's got me tagged, he's told me too much, I'll drop into a canal some night real soon, by his intention. I got to make the door, is all, that's all I can do, I can't think about food, can't stomach nothing, can't sleep while they got their hands on him—

Prison. O God. And what else?

"M'sera." She heard Boregy. Distantly. Talking to some woman. "Jones." Thatwas her. She turned around at the dizzy edge of the stairs, caught her balance and stared at him staring at her.

So what's he want? He going to stop me after all?

"Who have you mentioned our name to?"

"Nobody." She shook her head violently. "I ain't—"

Lord, is mat the thing he needs to know, 'fore they make some accident? Who's to care? Who's to care here?

"No one?"

"That's for me to know," she said, and turned and negotiated the stairs. Balance faltered. The whole world came closer and farther by turns, went fuzzy and came clear again, the hall with its veined red stone, its glare of electrics.

A hand caught her elbow. She shook it off and it came back. So she walked to the door and down the steps, the rough stone steps that led down and down to the hall, to the porch-landing, to her boat that rode there in the rectangle of lamplight from the open door. She drew a breath to clear her aching head. The air was cold with the water, dank with the stone of the Cut vault. Iron and stone and rot. She started down the step. An elbow nudged her.

"Here," a man said, one of the three who had brought here downstairs. Coins shone in his outstretched hand, a scatter of silver and bronze in the lamplight. She stared down at it and up at him.

"That ain't no help," she said, not even bitter. A choking lump rose in her throat. "Damn, that ain't no help at all."

She stepped across to the deck, jerked the tie loose. " You mind if I start the motor in here?"

"The family would appreciate it if you'd—"

"Sure, sure." Tears dried and strength roared through her veins like a blast of heat. " 'Predate yourself to hell." She ran out the pole, with the water widening between herself and the Boregys. "Ye damn cowards!"

It was work turning the skip. Part of it was in the dark, when the men went back in and shut the door. Then wheels squealed, chain rattled, and the big Watergate began to admit the ghostly starlight-on-water of the canal outside. The breeze came back, skirled free into Boregy Cut, raced out again.

She drove with the pole, sent the skip scudding out the narrow opening, and made the turn that took it on in the dark, with the Signeury walls high and blank and grim, and Golden Bridge hung across the Grand like a dark webby strand across the Signeury's face.

She pushed it as far as the first bridge-pilings of the Golden, till her gut hurt and her sore feet burned on the deck. Then she lifted one hand in a rude gesture up at Boregy Isle and shipped the pole, went back to start the engine.

One try at the crank. Second, She fussed with the choke and her hands shook. A third jerk at the crank. Cough. A fourth. Cough and start. The breeze skipped and skirled round the corner of Boregy. She jammed her cap down, set the tiller and sat down to steer, the tiller tucked under her arm. The strength had gone, leaving cold behind, leaving shivers that drew her legs up and made her teeth chatter,

Prison, Him in prison,

A worse image occurred. She shut her eyes and opened them wide, trying to banish it, picture of a dark place and lamplight, like Bogar's basement, but no friends in sight, none, no hope and no help and no fair-minded council in judgment, only enemies.

O God. Tidewater. Tidewater and sea-gates. It's got to be. I come up the Snake onto the Grand just after that bell was ringing and they was there when that bell rung—they got Wesh for it—I wasn't that far behind, I almost saw 'em, I was that close, and I never saw any boat going down-Grand. Just that boat away on Margrave—on Margrave going west—Damn, I didsee 'em, they was going away, they had him in that boat, and me not knowing—

Of Tidewater gates there's Pogy and there's Wharf, and there's Marsh, over by Hafiz's. If it was flood they could go by the Port Gap, but they can't do that, they got to use the Gates, that prig Boregy's right in that. And tide don't crest till the top of the sixth. They got to—

She blinked, jerked her head up with the point of the Signeury wall coming up at her, veered wildly and veered again for the center of the channel as she headed for the massive pilings of Signeury Cross. She kept going into bridge-shadow, a place so dark there was no hint of obstacles and a body had to run it blind. The breeze gusted in sudden violence, turned colder. The motor echoed, a lonely throb that carried into her sore hand and aching elbow through the tiller, and she had not even the enthusiasm left to shift the bone off contact with the wood. Hurts, something distant told her. And: Good, her conscious mind answered back, because it kept her mind focused.

Damn stupid fool, where you going?

Mama, you got an answer for this one?

Hell, you got yourself a good one this time. Crazies. You ain't thinking, Altair. You checked that gun? You sure it's still there?

She reached in panic and opened the dropbox nearest the engine compartment. Her fingers found rags, burrowed to touch the smooth metal of the gun. Shells were there too, In their small box. She tested the weight. Intact. The blood sought its former course and her heart settled down to its exhausted throb, thumping along with the motor sound. She blinked, focused again. The headache was fiercest at the back and behind the eyes.

Damn smoke. Had that headache since the smoke. That pathat-stuff. All them that breathed it must be worse.

He's got to be sicker'n hell.

Mondragon—I'm trying. What'm I going to do, you knowing more'n I do—Sword of God and all, and what'm I? All them fellows and Moghi couldn't stop 'em, and they got canaler help, had to have been them on that canal, folk'd see 'em if they went to carrying a body very far over the bridges—

–Canalers. Canalers who'd do anything.

That's a longish list. That's the whole damn Tidewater and all the vermin in it.

Borg Isle passed, and Bucher.

Could turn off toward Malvino. Could go to them, maybe they got more guts than Boregy.

No. Uptowners. I was lucky once. I got out of there. I got all I can get. Next 'un might just cut my throat.

Where do I go? Which way? Cut off down by the Splice and go down West? Damn, where isever'body?

Under bridge shadow and on toward Porphyrio. Oldmarket Bridge was next. The tie-rings and the pilings had no boats, nothing, not even the shabby-canopied skip mat ought to be there. The engine throbbed on, drinking up the fuel.

I c'n turn off by Wex Bend—no. That damn bridge might be blocking it. Go off by Portmouth, pick up me Sanchez Branch and go by the West—

There wasa boat, a dark lump making rapid headway up the Grand from under Miller's Bridge, dead-center of the channel and spreading a starlit wake in a great V to either side.

Damn, it's under power, what is it, whois it up there?

The beat of that engine came off the walls, in and out of phase with hers. It was a skip. That could mean anybody. And the canal was deserted. That meant trouble.