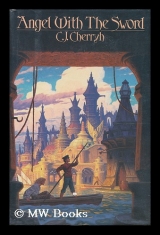

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

"Dizzy?" she asked. She preferred to talk to the fool. What she had seen in his face the moment before was not something to rouse. What she had seen flicker there told her she was a fool herself not to swing that tiller about and head back for the canals where there were witnesses and a way to get this fellow taken up by the law, if nothing else.

He nodded, looking drowned and dazed and compliant.

So he didn't want to run ashore with that rope and maybe be stranded if she took it in her head to do it. Standoff. Neither did she. She had a spot in view, let the boat chug up as close as put them in shore-shallows and killed the engine. She let down the tiller and dropped the stern-anchor, then skipped blithely off the halfdeck and down the well to pick up the bow anchor and heave that overboard.

Off-shore tieup. So they floated. That idea had its merits, considering the area.

She turned and looked at him where he sat on the deck, his feet in the well, on the slats. "Been managing this boat a long time with no help to hand," she said cheerfully.

"Safer to tie up here anyway. Crazies run the shore. With you all dizzy like that, I'd worry. Hate to think of you wobbling around like that if we had to put out real fast with shore under our bottom."

"Crazies."

She waved a hand off toward the rocks, the long ridge of the west Rim. "Rim there connects right onto the marsh. All sorts of crazies can walk here as well as float. Some won't hurt you. A lot will. You just sit there. I'll just set up work here, do a little fishing. If I sing out Pull the anchor, you get up to the bow and haul up on this rope here—" She put her bare foot on it. "That easy enough for you? I'll be aft hauling up the other, and there'll be some real good reason for it. Not likely to happen. But just so's we don't cross paths on the deck. Knock each other in the wash, we would. Rules of the deck; poleman has right of way. I move with that pole and you're in my way, you just fall down and be walked on. You foul me, we could hole this boat or I could hit you in the head and you don't need another lump, do you? Second rule: you don't touch my gear. It's right where I need it. I got two calls I use: I yell Deck, hey! you just fall flat, like with the pole: this here's a small boat, and it's real easy to get your skull cracked. If I yell Scup! that means something's loose and you grab it. Got no time on a boat to explain things." She drew breath. It hardly mattered. Getting rid of him was the idea. Not attracting undue attention with him was the principal problem. "Got to do something about that head of yours. Never saw hair that blond. Anybody looking for you, you shine like a beacon." She walked on up to the halfdeck and rummaged in the first drop-bin along the side. There was a scrap of a black shibba shawl she used for a towel. It was clean. Mostly. She sniffed it and threw it at him. "Wrap that round your head. Look like a proper rafter, you will."

He looked nonplussed. "Damn. Dumb." She came and snatched it out of his hands and wrapped it for him, turbanlike, herself up close against him.

She had not thought about it when she started; she did before she was done, and she backed off when she had given the cloth its final tuck, with the same embarrassed unease she had had in the night—that he was not a boy, not just anyone, and the only company in her whole life had been female. He was just—different. Touching him felt different; and it reminded her that when she had offered him what she thought was the most profoundly generous thing she had ever offered, he had flinched. Nothing so calculated as a No. Just a gut reaction from a dazed man, honest as it came. She had herself up in his face and he just sat there. Never did what a man ought to do, just tried not to notice.

I never thought I was pretty. I never thought I was that bad. She touched her nose where she and the pole had met, hard, when she was a girl struggling to learn the boat. When she was slow getting to safe mooring in a storm, and old Det got his knock in, back when she was first alone and not so strong as she was now: first time she had ever poled alone in bad storm, and got her nose broken. She had gotten to mooring choking on blood and half-blind with pain; but got to mooring. The nose was always a little flat, a little broad. Maybe it was that. It was sure the pole hadn't helped.

"Why are you helping me?"

She looked back. Hunted a quick answer and discovered it made no sense. "Huh. I dunno."

He thought a moment. He had that look, that there was thinking going on. "How did I get aboard?"

"I pulled you."

"Yourself?"

"Who else?" she asked. "You tried to climb aboard. I grabbed you and I pulled."

He shook his head. "I don't remember. That's gone, I remember the water. I remember a bridge."

"Half a dozen friendly fellows threw you off, nakeder 'n a newborn. Don't remember, huh?"

He said nothing. That saying nothing was a lie. She saw it in the little flicker of his eyes. He looked around. "What are we waiting for?"

"You got a place to go?"

He looked at her.

"You can rest," she said. "Sun's coming up warm, you just lie there and bake those scratches till you feel better. No hurry." She walked over to starboard and got the lines and poles from their ties, skipped up onto the halfdeck and drew the stern anchor tighter. She heard him move and looked around to find him clambering up onto the halfdeck, swaying perilously rimward. He staggered again. "Deck!" she yelled, gut instinct; and he wobbled there widelegged till she grabbed him. "Sit down! Damn, you near went in!"

He caught at her arm and sat down on the halfdeck, all wobbles. She squatted on secure bare feet and the facts slowly dawned on her. She became aware of the little scrunches her toes made, the constant shift of her leg muscles. She reached and shoved at his knees. "Hey, you keep your feet down in the well, huh? Don't you stand up on the halfdeck, and you be damn careful standing up in the well. You got landlegs, not to mention a cracked skull, which don't help. Little boat does pitch a bit. You'll get used to it. You're wearing all the dry clothes I got."

He swung his feet down onto the slats. Looked back at her. "What are the sanitary arrangements?"

"Sanitary?"

"Toilet." And when she blinked in dull amazement: " Piss!' he shouted at her.

"There's that pot there for'ard and there's over the side, you takes your pick. Either you got to do." An image occurred to her. "Piss over the side; you got to do something else, you use that bucket; Ican do't; you'll fall in sure if you try the other."

He looked at her and looked forward and aft and back again as if he hoped for something else. And sat where he was.

She felt genuinely sorry for him; and irritated. And personally insulted. Like the flinching-away from her. It was one and the same. She reached out and patted his hand much the same as she had touched the ingrate cat—quickly and carefully. "Hey, I'll be fishing off the stem, all right?

I won't look."

He stared at her as if he thought there was surely some better answer.

"You some kind of religious?" she asked, as the thought leaped into her head. Some Revenantists were extreme in their modesty.

"No," he said.

"You like men?"

"No." More emphatic than the last. He looked desperate.

"Just not me, huh? Fine. I won't jump you. You don't have to look so worried." She patted his hand again and got up and went over and squatted down on the half-deck at the drop-bin where the rest of the tackle was stowed, meticulously untied it and tied lines and uncapped the bait-jar, wrinkling up her nose at the stench. She wadded a bit of it on one hook and cast.

She sat down then crosslegged on the stern by the engine housing and watched the float and the water and the dancing sunlight, same as a thousand days and a thousand more. Until finally she felt the little difference in the boat his moving about made; felt it in the way the balance and character of the boat went right up her spine and into every nerve. She let him be. Eventually he came back toward the halfdeck; and got up on it. She turned around, but he was being careful, walking bent over with his hand ready to the deck.

He wanted the company, she guessed as he settled near her. It was all right. It was pleasant. "You ever fish?" she asked. It was not a hightowner kind of business, but it was a thing she liked to do when business was slow. Best thing in the world, to watch the water dance and hope for a bobble in the float; it was all hope. At any moment luck could turn. A fisher had to be an optimist. A pessimist could never stand it.

"I—" He edged closer and started to sit down and drop his feet off the side.

"Hey, you'll scare the fish. Keep your shadow off the water, huh?"

"I'm sorry." He got back and tucked his feet up in his long arms. She turned and gave him a look to say it was not unfriendliness. "I—" He tried again. "I'm really grateful," he said. "For everything."

She shrugged, suddenly dragged back to business and feeling a little chill in the world. Bridges at midnight and black-cloaked no-goods. She looked at him.

"It's not that I don't—like you," he said. "I just– don't know what's going on."

"You mean you don't know who threw you in."

That wasn'twhat he didn't know. She read the eyes, the quick unfocusing and dart elsewhere and back.

"How did you happen to be there?"

"I was making a pickup at the tavern. You went in right near my boat. You come up looking for anything to grab. I was it. Lucky, I s'pose."

He digested that for a moment. The eyes flickered. They were green like the sea. No, murkier. Like the sea on a bad day. Then the cloud in them went away and he reached toward her face. She flinched in startlement.

He drew back quickly and looked uncomfortable.

"Hey," she said. It scared her. Her heart was pounding. Ancestors knew, he could be crazy as half the rafters out here. She took up on the pole. "I think I got a bite." It was a lie. It got her out of an uncomfortable situation. She wound the line in and examined the dangling float and hook. The bait was gone. "Damn sneak." She got up and went after more bait.

She cast again and fished standing up until he stretched out on the warm halfdeck boards and just went to sleep. Then she sat down, and fished, and reminded herself all she had to do was give him one good shove: that landsman wobble of his was no pretense, whatever the rest of it was.

He lay there, sprawled like an innocent in the sun, and she caught a little fish. She chopped it up for bait and fished the morning away with the heavy tackle.

He waked when she brought the first good one in. He scrambled in a hurry when it landed on the half-deck flapping and flopping and spattered water all over him.

"Lively," she snapped at him, because he was within reach of it. He grabbed and got finned and grabbed it again. "Line!" she said, and he grabbed that and got it under control.

She got the hook out and put the fish on the stringer and dropped it over the side. "How's the hand?"

He showed a wound he had been sucking on, a good few punctures.

"You really are a son of the Ancestors, ain't you? That'll be sore."

He looked at her in offense and never said a word.

"I know," she said, "they don't teach you about fish uptown, you just eat 'em, My fault. Never thought you'd grab it on the back. Behind the fin and by the line. Least it didn't have teeth. Redfin, now, I wouldn't have had you grab that. Bad fins and they got teeth besides. You use a glove with that, that's all. Same with yellowbellies. Take a nice nip out of you. And deathangels, they're just what they say, they got poison'll kill you dead quicker'n you can turn around. Nice eating, but one of them spines can kill you three days after that fish was supper."

"I know that," he said somberly; and she remembered about assassins and deathangels; and the high bridges; and got another chill in the daylight. She rebaited her hook and turned and cast again. A flight of seabirds landed out by the Ghost Fleet, and raft-dwellers began a slow, drifting stalk. She watched them till the flock took flight.

By noon it was fish cooking on her little stove; and full stomachs and a nap afterward, herself on one side of the halfdeck, himself sleeping sitting up, where he had fallen asleep after lunch, down in the well. On a good slug of Hafiz's cheap whiskey and a bellyful of Dead Harbor fish.

She woke from time to time, looked over her pillowing arm to have a look at the shore, which was bare brown rock and yellow shingle; and at the passenger, whose only move had been to lie down on his side on the slats with his head on his arm. There he stayed, tucked up like a baby, one bare foot engagingly lucked behind the other knee.

The sun was warm, the night had been hard, and she blinked out and let her head down to her arm again, too sleepy to do otherwise.

By late afternoon she fried some pan-bread to have with cold fish; and Mondragon-whatever came up and looked at the proceedings. "Have you got a razor?" he asked.

"Got a good knife," she said, thinking about it. "She's razor-sharp." She had the boathook in reach, and it was an honest question: he had a good stubble by now. She ducked aside and handed him up her ribbon-thin sheath knife, notthe one she beheaded fish with. He looked doubtful till he tried his thumb on the edge and then he looked respectful of it.

"What do you use, whetstone?"

"Bluestone and you be damn careful." She drew the stone from her left pocket and handed it up.

"Soap."

"'S in the can. There first as you go in the hidey. Little black can. You wait. We got supper coming."

"I reckoned to be clean for dinner."

"Lord, you gota bath last night."

He looked at her with such dumbfounded offense that she shut her mouth outright while he bent down and got the soap out of the can. A bath. After near drowning. With soap.

He went off to the rail and pulled off his sweater.

"I bet you hope I got clean clothes, too!" she yelled in derision.

He turned around. "I wish you had," he said fervently. And turned again and stripped off the too-large breeches, gathered up the knife and soap-cake in one hand, and launched himself in a shallow dive off the side.

"Damn!" It was not particularly deep at that side of the boat. She sprang up and ran to see if he had broken his neck, but there he was, swimming quite nicely. "You ever look where you are?"

"I'm all right."

"Damn, you lose my knife I'll make you find it before you get aboard."

He stood up, water at mid-chest, and held it up. Along with the soap. He wrinkled his nose. "Is something burning?"

" Damn!" she yelled, and ran back.

It was burned. She turned out the black-bottomed bread onto the cold fish, put out the fire and sat there staring at the mess.

Then she pulled her sweater off, unfastened her breeches and went off the other side of the boat.

Second bath in a day. If he could be clean, she could be cleaner. She came up and kept the boat between them.

"You all right?" he asked from his side.

"I'm fine. Dinner's already burned. Might as well be cold too." She ducked again. The bottom was silty sand and felt awful. She tucked her feet up, swam a few strokes out and flipped and started to swim back.

He came round the edge of the boat, "You want the soap?"

She trod water, not standing up; and swam to his outstretched hand and got it. He went back around to his side. She scrubbed and spat and swore, and when she had scrubbed enough for ten women she laid the soap up on the half-deck and swam round to the side, came up over the rim on her belly and slid over into the well.

Back in possession of the boat. He had a good view out where he was. She refused to notice that or to look his way. She walked up on the halfdeck and put her breeches and her sweater on, stowed the soap, and sat there and ate her dinner with her hair dripping onto her shoulders.

So hehad to come back aboard. She stared mercilessly, while he turned his back to dress and pretended quite as well that she was not there. He had come back with the knife. She saw that. And when he came her way with it she had the barrelhook down by her foot just in case. She looked up as he sat down with the bluestone from his pocket and caught a little grease up from the skillet; he proceeded to care for the blade (she had to admit) right properly.

"You can eat," she said.

"I'm taking care of your property."

"I can do it fine. Eat."

He kept working at it. A long while. She finished and went to the side and swept the bones of her portion off; wiped the plate off to stow it.

Then he ate his own and took the skillet to the side. Dunked it.

"Damn, what are you doing?"

He looked back at her. "Washing. Does washever—?" He cut that off before it went too far, but she caught it well enough.

"You don't wash an iron skillet, Mondragon. You wipe it. Just gets better. And you go washing your plates in the harbor, you get sick. You go wash too damn much you get sick. I don't like being dirty. But there ain't no damn place to wash, Mondragon, till it rains, and then it's too damn cold!"

She screamed it at him. Realized she was screaming, and shut it down with an exasperated heave of breath.

"I'm sorry," he said.

"Hey, you do all right for a landsman. You didn't even lose the soap."

"What do I do with the skillet?"

"Here." She took it and wiped it with a rag and stowed it. "First heat-up'll kill the germs. Skillet's the safest thing you could dunk."

"Bread wasn't bad."

"Thanks." She put the number two droplid down on the dishes and sat down on the halfdeck rim, bent down and got the whiskey bottle. She wanteda drink. Lord and Ancestors, he made a body want a drink.

She held it out to him then, figuring she might make him want one too. "Trade you for my knife."

He passed it and the bluestone, and took the whiskey and drank.

The bottle went back and forth several times; and she sighed then and looked at the bottle. An inch of amber fluid remained. "Oh, hell," she said, and passed it to him. He drank. She finished it.

Then she went back and fished some more, finding tranquility in the business. Across the water lights showed from Merovingen, a scatter of gold above the darkening waters. The water lapped and slapped and glittered, broken reflection of the fading sky. The float bobbed away, untroubled.

He moved up beside her on the deck, sat crosslegged. Silent. Water-watching. Thinking mist-thoughts, maybe, how old Det had tried for him and lost.

"You're real lucky," she said finally, out of her own. "Drink that old canal water, you get fever. You must've drunk a liter of it. Kept waiting all night for you to fever up. Maybe the whiskey killed the germs."

"Pills," he said. "I took a lot of pills against the water."

She turned her head. Pills. "You mean you knew somebody was going to throw you in?"

"No. The water all over Merovingen. Bad pipes. They say you have to be born here to drink it."

"You weren't."

"No."

"Where from?"

Silence.

She shrugged. A lot of river-rats and canalers had the same habit. Keeping to their own business. She got a nibble and missed the set when she jerked it. "Damn." She reeled the line in peered at the hook in the gathering night and had to take it in her hand to discover the hook had been cleaned. "Fish was supposed to be our breakfast. Didn't go to give him his."

"You live alone?"

That question made her nervous. "Sometimes. Got a lot of friends." She looked at the onsetting dark and sighed. "Well, no luck." She secured the tackle and put it away, lashed it neatly to the side near the rim-rail of the halfdeck.

And turned where she sat and looked at him where he sat, none so far on the narrow deck, in the last visible light. Her heart was beating hard again, for no sensible reason. Is that reasonable? What'm I scared of?

Oh, nothing. Six black skulkers who murder people and a man sitting in my boat in the dark, that's nothing.

They're probably looking all over for him. What if they found us?

He knows who they were.

She slid off the halfdeck and stood up in the well. He slid to the edge and set his feet over, got them out of the way as she bent and pulled a blanket from the hidey. "I'll sleep on the deck," she said, and did not add: you'd fall off. But she thought it. She stepped up on the deck and felt his hand on her ankle, not holding, just—there, and on her calf when she did stop.

"I don't want to put you out of your bed."

"That's fine. You want it, Iwon't roll over the side." She shook free and sat down, flinging the blanket around her. "I'll be just fine."

He reached out and put his hand on her knee this time. "Jones. Listen—I never meant to put you off. I just—hell, I'm shaken up, Jones, I don't know what I said. I think I insulted you. Come on. Come on inside."

"Cleaner up here." Of a sudden it was going the way she wanted lastnight; but it was not last night, she was not half that crazy, and she was scared.

"Come on," he said, rocked at her knee. "Come on, Jones."

Coward, she told herself. She sat there a good long while, and he sat still, showing no sign of going away.

"All right," she said, and edged toward the rim of the deck. He reached out a hand and steadied her—as if hecould keep his feet. She got down on her knees and dragged the blanket into the hidey, and he came in after. Then came a great muddle of blanket-arranging, so that she banged her head in her nervousness. "Damn." Nothing went quite right. She lay down and he just lay there. "You going to do anything?" she asked finally.

"You want me to?"

"Damn! You son of the Ancestors, you—" She flung herself up on her elbows and began wriggling out as if the boat were afire.

He grabbed at her and she elbowed him hard enough to get a sound out of him. He grabbed her hard then and got a knee over her midriff, holding onto her hands. "Jones. Jones—" And then he worked that far down the hidey too, and it was clear he had made up his mind.

In a little while she made up hers at least for the time being; clothes got shoved to this side and that and the blankets got tangled; she hit her head again in the throes of what he was doing and nearly knocked herself dim-witted. She fell right back down on him and lay there swearing while he gently probed the egg on the back of her skull. "Oh, damn, Jones, I'm sorry."

4'Got a matching set," she said. He had a good one on his. She knew. She lay there warm and comfortable on a breathing human body, with someone's arms around her for the first time in years. And it was somewhere far and above the way she expected. He was clean and tried not to hurt her: ("Damn, girl, this your first?"—"Shut up! Don't you call me girl!" He shut up. And was worried about her, and when it got beyond hurting he made her forget it hurt.) He told her things and taught her things in his polite way, so she didn't say them hers: somehow it belonged with fine words, what he did; and what she expected belonged with hers.

Somehow it fit that she banged her head twice on her own overhead. She felt awkward; and kept quiet the way she took two baths in one day, not to have him look down on her. But karma took a hand and she made a fool of herself twice in the same night. And landed dazed on his chest and had his fine hands to take the hurt away.

She was in love. For at least the night.

You got no sense, Jones. You're a real daughter of the Ancestors. You know this Mondragon? You got any idea why six people want to throw him in the Grand? Maybe they had reason.

He couldn'tbe on the wrong side of it. If he was a murderer or a thief or a crazy I'd know it by now.

He's got to go back where he belongs. I got to get him there. He don't belong in a place like this.

Her heart hurt. It knotted up and hurt as if her whole self was trying to shrink up in that small space. His fingers worked at her shoulders.

"Jones, something wrong?"

"Nothing's wrong." Her shoulders were tight. She realized he was working at over-tense muscles and tried to relax.

"You sorry?"

"No. No." She sucked in her breath. Spilling tomorrow on today, her mother called it. Damn nonsense. Today was fine. Tomorrow—well, tomorrow could maybe be twodays away. Then it was time to use her wits and get him back where he belonged. She drew a breath and let it go. And snuggled up against his shoulder and tried to shut her eyes.

She opened them again at once. Sometimes she heard things at the edge of sleep, time doing tricks, things that might or might not be there.

But the waves had a rhythm. It was always there. The boat had a way of moving. The world rocked and moved forever in certain ways and with certain sounds; and right now, for no reason she had heard clearly, a cold bit of fear gathered in her gut. She tensed and started to get up; his hand pressed against her back. She put a quick hand over his mouth. "I think I heard something. I'm going to back out real easy. Stay put."

She eased back and felt him start to follow. She pushed him back. "No. Stay out of it." She had a vision of him stumbling about in the dark. "I got ways." She went on sliding, the wind cold on bare skin; came out into the starlight on her belly and came up on her hands ever so carefully to peer over the deck-rim.

A raft was out there, dark, amorphous island in the starlit water. She got the knife at the hidey entrance and slithered on her elbows down the well, cut the anchor rope with one quick slice, backed up and around and hewas out in the starlight, keeping low as she was. She slithered back in a hurry. "Keep your head down," she whis pered under the water-noise. "We got a raft out there. Thing can't move for spit, but they're crazies for sure." They were in the deepest part of the well; she grabbed a towel off the slats, rolled to get it on and knotted it around her waist while he grabbed his pants. Then she rose up and put her hand on the deckrim; he grabbed her arm.

"Where are you going?"

"I'm going to start the engine. You want to crawl back there with me and cut that anchor rope?"

"Does that thing always start?"

"Fifty-fifty," she said. She did not like to think about that. She slapped the knife into his hand. "Get that rope cut. I know my engine."

She eeled up over the deck, slithered across quick as she could and got up on her knees behind the engine housing to lift the wooden cover, while Mondragon was at the rope.

Careful now, step by step and precise with the start-up. The old engine was fussy; it preferred the warm sun to damp nights.

The crazies saw her. There was an outright splash from the polers on the raft. A rising mutter of whispers in the dark: that became voices—

Pump some fuel up, set the switch, wish to God she'd cleaned the contact and checked the gap today—Ancestors, save a fool! Her eyes picked up another bobbing darkness, second raft beyond the first, and real terror went through her. Mondragon was on his knees beside her, the boat was slewing free and the traitor backsurge was carrying them toward the rafts—She heaved the crank round once, twice, steadied the choke against its tendency to suck in too far, heard howls break out across the water and heaved on the crank again, O God, not a sound from the engine. Adjust the throttle again; crank. A little hiccup. Back the choke out, just on the worn spot in the shaft; crank. Hiccup-hiccup.

"Jones-"

"Get the damn boathook! In the rack! Move!" Open the stop, drain the line down, she'll flood otherwise; the smell of fuel hit the air, and Mondragon was scrambling after the pole-rack, on his feet, the boat pitching as it slewed and bobbed to wave action and the rafts—God, God, threeof them, one on the other angle, moving in with howls and hoots and splashes of water—Steady that choke, remember the throttle, back her down, crank again—hiccup. Damnit, engine! Crank. The nearer raft bristled with boathooks, a spiny thing like a sea-star, all of them waving and the night filled with howls and hoots. Men leaped into the water and splashed toward them.

Crank, hiccup, cough. She let go the choke, feathered the throttle and lost it. The rafts were a wall of spines. Mondragon had the boathook in his hands. Reset the throttle. Back the choke. Crank. Double-cough. The engine started, solid. Feather the throttle back; engage the screw– Tiller bar up, fool! Rudder's still down. She snatched the bar up and set the pin, and scanned the shoreside water ahead, frantically searching the dark for rocks and sand as the boat gained a little way. No room, no damn room but a thread of water along the shore where rock or sand might set them aground and helpless.

She slowed the bow around, heading that way. Water splashed. Mondragon swung at something in the water– Don't hook 'em!" she yelled, "hit 'em! You can lose the pole—Yi" A swimmer was coming right up over the side. "Ware port, ware port, God, ware port!"

He finally saw it and swung the pole into the boarder's skull just as the man hit their deck. Altair swung the tiller over and gritted her teeth as the surge and the boat's own sluggish way took them closer to the rafts than she wanted; or the rafts were closer to shore, poling more effectively in the shallows, and God knew where the bottom was under them right now—"Ware, ware, Mondragon look out!''

He was going to lose it, they were going to snag his hook and jerk him off, or get a hook into him—

"They'll try to snag the side! Mondragon, switch ends, switch ends, don't let 'em hook ye! Ware afore—"

Because they were going to skim close to the third raft, too close. She caught the dropbox handle at her foot with her toe and flipped it open, held the tiller with one hand and dived down and grabbed the pistol out– aimed it dead into the living wall that loomed up at an angle and squeezed the trigger the recoil jolted her arm, the report jolted her ears, and the crazies screeched in one great shriek as something hit the water and one voice screamed above the rest. Pole cracked against pole: she looked left where Mondragon was in the finish of a swing, and aimed past him at the waving arms and hooks. A howl and a shriek; and she kept the tiller under her arm and put her third shot into the raft coming up closer, with similar result. Her right arm ached; she had the tiller under the left one and leaned on it, trying to keep the boat as far from the raft as she could, trying to judge it tight between the reach of those poles and the hazard of that near beach.