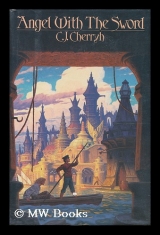

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

He turned and looked at her. The easy manner was gone, the humor fled. Yes. He was looking for them. For something. Plain as an answer.

"Yeah," she said. He said nothing. "Who were they?" she asked.

"I'll take care of it."

"Real fine. Maybe they'll be looking for me, you ever think of that?" She drew a breath, two. It was the Hanging Bridge ahead, and the current of the Snake's other exit. She fought it the moment it took.

"I thought of it."

"That's real nice."

"It wouldn't do you any good, Jones. It might do worse. Just stay clear of it. Far clear."

The sun was on them now, one of the only places on the Grand that had a view; which was what made the Hanging Bridge. It hove up, conspicuous with its fretworks and its angel and its ominous wooden arches.

"That's there's the Angel, shining there," Altair said, between pushes. "Revenantists say Merovingen'll stand long as the Angel stands on the bridge. Janes say he draws that sword a bit more every time the earth shakes. Adven-tists say he'll stand till Retribution."

"I've heard of him," Mondragon said. He turned his face to her again, looked ahead as they came closer to the bridge, looked back again.

She looked too, scanning the traffic. Her back prickled with the feeling she got skimming through some backwater. Running near crazies and rafters. Back to the starting-point. Fishmarket Bridge loomed beyond. There was Moghi's, dim and distant under Fishmarket shadow, Moghi's porch beyond Ventani Pier. There were skips and poleboats and the usual huddle of barges, the vegetable-sellers and the fish-sellers and the fish-freighters tied up to rings there by Fishmarket and spilling all the way along the edge. The wooden towers of Merovingen-above shone silver-gray in the sun above the dark, above the web of bridges beyond. And the Hanging Bridge Angel presided over it all, sword half-drawn. World half-ended.

Putting it away or taking it out again since the Great Quake?

Halfway between dooms.

She spied a place on the east bank and eased the bow over that way, there amongst the fish-sellers. Mondragon sat on the deck-edge, turned again to look up at her as they glided in.

Wondering what she wanted, maybe. Wondering how to make parting fast and clean. She was too busy; shipped the pole and took up the boathook. "Hey, Del," she hailed the old man of the neighboring skip, and snagged the ring, hauling mem close. She bent and took up the mooring rope one-handed, ran in through the ring and made them fast. Hopped down and walked up forward where her bow touched the other skip. "Hey, Del, you want to give me a bow tie-up there?"

"What you selling?"

"Not a thing. Not trading. Just a little stop."

No competition. Del Suleiman's old mouth snaggled into a grin. "I take 'er. Tie on."

"Well, you got to lend me the rope, I lost my anchor stem and bow."

White brows went up and lowered again. A scraggle-bearded chin worked. A gap-toothed woman sat aft on the half-deck, female mountain behind the baskets of eels. "How'd ye lose 'er?"

"Hey, got a lander." She reset her cap and in the move brushed knuckle to right eyebrow: got business going with this landsman; settle ours later. The old man grinned and the woman grinned and the old man got his boathook to do the tie-up.

She walked back to Mondragon, who stood in the well within a stride of the stone walk. Waiting on her.

He stood there a moment longer, looking into her eyes. And for a moment she remembered the sun on him in the morning.

Then he turned and skipped up onto the landing, barefoot as a canaler, in her misfit breeches, a blue sweater out at the elbows and a black turban that did nothing to hide that white, sun-burned skin of his. He looked back from that vantage. Once.

She stood with her hands in her waistband and her bare feet solid on her deck. "Luck," she said. "Mind your back next time."

It got a flicker from him, as if that had shot true. "Luck," he said, and turned and headed for the stairs.

Not another look back. Not one.

Not an offer to bring the clothes back. Too rich to think it was all she had but what she was wearing.

Or just not going to promise what he couldn't do.

She turned and walked down to the bow where old Del was tying up. She squatted down there. "Del, what I got to give you so's you watch my boat?"

The old man's wits were sharp. His face never looked it. He chewed the cud he had, spat a little green juice overside between her bow and his side. "Hey, watcher into, Jones? You clean?"

"Swear." She lifted a solemn hand. "What I got to give you?"

"I think on 'er."

"Well, think, ye damn sherk!" Altair sprang up in despair. Old Del knew how to wring advantage out of a bargain, and retreating quarry was a mighty lever. "I'll pay you, I'll pay you, my heart's blood I'll pay you; and heaven help you if I got a scratch on my boat!" She pelted up the slats, grabbed up the knife and the barrelhook and hit the stones running. Hooo—oo! The appreciation of other canalers followed that bit of theater. Hooo—Run for 'er, Jones! Hooo—Del!

Damn. He could get away, go either direction. She thumped up the age-smooth wood of the Hanging Stair, up and up the four turns to the wide bridge and its gallows-arches.

There, blue sweater and black turban heading over the bridge to Ventani.

Headed right for the neighborhood that dumped him into old man Det's jaws in the first place.

Man with his mind set on trouble, that was what. Crazy man. Crazy as the rafters.

She headed after him, bare feet soft-silent on the boards, belting on her knife and hanging the barrelhook from that belt too.

Chapter 4

NOW it was a real fool went racing across that bridge. And one following after him, barefoot on the sun-warmed planks, a canaler among the hightowners—the folk in plain chambrys and leather, the tradesfolk and the hightown shopfolk; and Signeury guards and sober Collegians and the highest of the hightowners, uptown folk all decked in lace and fine fabrics and dainty heeled shoes that rat-tat-tatted on the boards like a holiday drummer. A sweet-seller bawled her wares at bridgehead, beneath the ominous, thoughtful face of the Angel, whose gilt hand was on his sword. Altair strode past and imagined the sword regretfully shoved an immeasurable fraction back into its sheath: a fool's act put off the Retribution. Daughter, the Angel would say, his grave beautiful face very like Mondragon's, just whyare you doing this?

And she would stand and stammer and say: Retribution (the Angel had her mother's name), I dunno, but excuse me now (hasty mental curtsy), there's the other fool and he's off down the walk, I daren't run—Let me keep up with him, Angel, I'll mind my business tomorrow, I will—

She pattered off the bridge and along the side of Ventani Isle, on its balconies, with its higher-level bridges in still more layers above, that shadowed Margrave Canal and Coffin Bridge and sent a few bright stripes on sunlight right down onto the walk. A merchant had set a potted plant in one broad stripe, possessor of a bit of sun, precious commodity on this level. An old man dozed in another patch of light.

Ahead in the crowd, Mondragon walked more slowly now; so she did, keeping that black scarf and blue sweater in sight. A canaler moved quite freely on this level, nothing at all remarkable. Someone on an errand. Someone taking an order. Moghi's Tavern was on the waterfront down below, at the Ventani's opposite comer, that which supported Fishmarket Bridge; but Mondragon, if he was going to Fishmarket, was certainly taking a roundabout route.

No. He took the short span over to Princeton, where it was much harder to track him without being seen. She reached Princeton Bridge and lounged there against the post for a moment until she saw her quarry take out to the right, down Princeton Walk.

She hurried then, walked along with a canaler's habitually rolling gait.

See the fool up there. Dressed like a canalrat, he is, and walks like a landsman for all to see. Landsman might not notice. But a canaler would notice something wrong, and look twice at him, and that twice might be trouble for him, might for sure—

Right across to Calliste Isle. Headed uptown. She strolled along with ease, took her time and faded back against the shopfronts and the posts among the passers-by when he would stop and take a look around him.

–So he's worried. He thinks about who might see him. He's trying to act natural and he daren't take to the high bridges, no, got to keep to the low, got to creep about down here with us canalers and the rats, he does.

Thank ye, Angel. He's being real easy. And if he goes back for Fishmarket round the Calliste I'll know he's a proper fool.

No, It was on north again, over the bridge to Van Isle and never a hint of stopping. A canaler passed him and stopped against Van Bridge rail and stared at his back; it was halfblind Ness. And Ness was still doing that when Altair walked past trying her best to look nonchalant.

"Hey," Ness said. " 'lo."

"Hey," Altair said, not to make a scene; and Mondragon was plainly in sight and had to be as long as he was on that bridge. A man hailed you politely, you hailed back. "I got a 'pointment, Ness. How you doing?"

"Oh, fair. Hey, you dobe in some hurry—"

Altair simply left him, for Mondragon took an unexpected turn south. She hurried across the bridge, and took out on the same tack.

Round the band of Yan then, round and on round, and onto the short bridge and across to Williams and the Salazar, which fronted on Port Canal.

I could have ferried him here easy as not. Notthat much further. What's he into? Why's he afraid of me letting him out at Port? Afraid of who could see him? Not wanting meto see?

Why?

Her heart thumped. Mondragon had slipped aside into a galleria that pierced Salazar's second level. She headed after him at greater speed, closing the gap in this darker place, this wooden cavern teeming with marketers and crowded with leather goods and shoemakers. Merchants bawled after shoppers. Merchants shouted at leather-dealers. The whole place smelled of leathers and oils above the prevalent canal-smell. And sunlight pierced it all by portsoleils and at the end, throwing figures into silhouette where the galleria turned out onto Port Canal, making everyone alike and without detail. She kept going, having lost her quarry for a moment, blinked when she came out into the sunlight and then caught sight of him on the bridge that led over north, to Mars.

Lord, the man's trying to kill me. No. Hehad rested the entire trip up from the harbor, that was how he moved so quick. Her side hurt again. Her feet felt stripped of calluses. He kept going round the side of Mars and over the bridge to Gallandry and around the corner.

And he vanished, before she could round the side of Gallandry. She took a running step, plastered herself to the stone side of Gallandry and took a quick look down the cut that led most of the way through Gallandry Isle, roofed with a solid next floor overhead, but not below, where an iron-failed balcony overlooked the water: narrow dark little nook of Gallandry business, the Gallandrys being shippers, factors, importers who sent their big motor-barges up and down the Port and the Grand.

Down that brick-floored balcony Mondragon knocked at a door. And talked with someone and got in.

So. Altair slumped against the wall, disheartened.

Gallandry. Gallandry was hardly interesting. Importers. Freighters. Traders. Certainly not among the uptown families.

Well, how could anything that came to her be more wonderful than that? How could he be more than that, some upriver merchant's son in difficulty in a canalside dive. Offend one of the Families, insult someone like the Mantovans or even some canalside riffraff, and get dumped in to feed the fishes. Easy as that.

So he went to his Merovingian factor to get money and clothes on his papa's name, and maybe to hire revenge. Simple. Simple done. Thento the Det and the boat before it left, probably on one of the Gallandry barges, probably hiding till they could spirit him out of town, safe and proper.

She gave a great sigh. It ached all the way to the bottom of her heart and she nursed an aching side and sore feet. It was nothing she could pursue further. It was nothing she had any more claim on—unless she walked up and rapped on the door and said Mondragon, give me my domes back.

He might talk the Gallandrys into giving her a reward. And wish to his Ancestors she was not there in front of his business partners.

If she was not a fool she would embarrass him right proper, get all the money she could. Maybe hold out for doing light freight for the Gallandrys. That favor was worth a damnsight more than any coin. Canalers would respect her then, by the Ancestors.

She slid down to squat on her heels, pushed her cap back and ran a hand through her hair.

Fool. Triple fool. I'm sorry, Angel. I'll be sane tomorrow; but hanged if I'll beg, damn him. Could have said right out Jones, take me to Port Canal, take me to Gallandry. Icould have done 'er, easy as spit.

Come up with me, he could have said, come on, Jones, want you to meet these folk.

He could have given me my damn clothes back.

Could have said goodbye proper at the Gallandry landing, he could. 'Bye, Jones. Been nice. Don't'spect I'll see you again, but good luck to ye.

She gnawed a hangnail, spat, cast a look back down the stone wall to the door, invisible from her angle.

Why didn't he have me take him here?

What's he up to?

The pain stopped. There began to be prickling up her back.

What's the fool up to? What's he doing in there?

Is he all right in there?

Damn, no, it ain't all on the table. Skulk over here, dive in a door in this damn gallery, disappear like that—Whoever he's meeting here is somebody he knows, somebody maybe a friend, but he ain't wanting to be seen, ain't wanting me to know—

– Stay out of my business, Jones.

Damnfool. Trust the Gallandrys. Maybe. Maybe about as far as you can trust any of the breed. They'll cut your throat, Mondragon, fool.

Or maybe you're a meaner fellow than they want to take on.

Not if they didn't push you so's you knew it, maybe. Not if you didn't see it coming, and, Lord and Ancestors, you didn't see that coming that near cracked your skull for you, now, did you? And you don't damn well know Merovingen, had to ask me things a man ought to know if he knew Merovingen, didn't you, Mondragon?

She reset her cap on her head, jammed it down and finally got up—walked quietly down the deserted dark gallery and stopped at the door. She took a further chance and set her ear against it.

There were voices. None of them were raised. The words were all a mumble.

She padded back where she had come from. Over the iron rail beside her, the gallery ended in a black watt and a watery bottom, a cut where a big barge could moor safely for loading. Green-black water, beyond all direct touch of sun. She went back into the sunlight on her end, where she could pretend to be about some honest business—but traffic was sparse here. A few passers-by. She sat herself down on the brick balcony with her feet adangle under the iron rail that overlooked wide Port Canal, just sat, elbows on the bottom rail, feet swinging, like any idle canaler waiting on a bit of business in a Gallandry office. And meanwhile she had that door under the tail of her eye and not a way in the world he could get out on this level without her knowing.

On this level. That was what gnawed at her. There were inside stairs in such buildings. There were ways to come and go. He could go in here and come out up above, on some upper level, clear across the building. Bridges laced back and forth to Gallandry on still another level, going back across the Port, over the West Canal to Mars or diNero and places north. Near a dozen bridges, most of them blind from where she sat. It was hopeless, if that was what he did. Unless—

She suddenly realized another fixture of the area, a man sitting the same as she was, over on the balcony of Arden Isle, next level up.

She did not look quick, but after a moment she glanced up again and scanned the area as if she were surveying the bridges.

Watcher on the West Arden bridge, too, on her level, just sitting.

Her heart beat faster. Gallandry folk? They might be. There were a lot of things they might be. She got up slowly, dusted herself off and leaned her elbows on the rail, looking down Port Canal, watching the traffic go, watching a slow barge and a flotilla of skips and poleboats. Shifted her eye back to Arden again. The watcher up there had moved, sat with one leg over the balcony rim; his hands made motions like whittling.

Damn. Damn. Real nervous sorts.

They got him under their eye.

They got me, too.

Fool, Jones, you got no protection.

Hope he walks right out that door with a dozen Gallandrys.

No, damn, I hope he don't. Him and all the Gallandrys'd walk right into it. Lord knows—they could be law watching the place. What if they're the law. What's Mondragon into?

If they're blacklegs, they can sweep me up right with the Gallandrys and all. Sweep me up to talk to even if they can't get him, if they're close enough to see me clear.

They might not belaw either.

Oh, Jones, what have you got yourself into?

How'd they pick him up? Waiting ail up and down the Grand? On the Ventani? No, dammit, there're too many, they'd have to get word out—They were watching Gallandry already. Either they're Gallandry or blacklegs or maybe some gang, and what's mychances of walking out of here by any bridge, huh, Jones?

Mondragon goes his way and some damn Gallandry knifes me on a bridge, he does, just precautionary. What's a dead water-rat, come floating down the Port tomorrow morning with the garbage?

She drew in a slow breath, shifted her eye toward the barge-gallery and worked her fingers together.

Law could have been watching Gallandry all this time. Anybodycould. Mondragon, you walked into a trap, you're in it up to your ears, Mondragon.

She rose and dusted off her breeches again, shoved her cap back and scratched her head. Put her hands in her hip pockets and strolled a dozen paces down the balcony toward Mars. Then back again. Stop. Take the pose of a canaler tired of waiting. She stood on one foot, brought the other up to her knee and examined the calluses, pretended to pick a splinter. Then she took a stroll down the shadowed gallery again, hands in pockets, the very image of a boatman gone impatient over a wait.

She knocked at the door. Knocked again.

It opened. A man in work-clothes towered in the doorway. "Hey," she said, "is my partner through in here yet?"

The man had a heavy face; big gut. He filled the door way but around the edges of him there was sight of windows on the canalside that let in light; there was the expected lot of desks and clutter; another man, the same sort, standing back alongside a lot of boxes. The heavy-faced man looked disturbed and confused. Then: "Come on in." He moved his bulk aside and Altair stepped up on the sill and got through that little space he left into the room.

Boxes and desk and papers and more boxes. Two windows. A door that made this room only half the space available on this floor. No Mondragon. And Man Two was moving up like a fish on bait, while Man One shoved the door shut at her side and set his bulk ominously in front of it.

"What's this about a partner?" Man Two asked.

Altair swallowed hard. Her heart was trying to come up her windpipe. She hooked a thumb toward Port Canal in general.''What you got out there, ser, is eyes all over this place. I got two watchers in sight meself, and they don't look friendly. I figure they got all the bridges off Gallandry blocked. So if you'd kindly tell my partner, I think I'd like to talk to him."

"What partner?" Man Two asked.

Oh, here it is. Body sinks real good, Jones, with a couple of rocks. Right to the bottom of Gallandry-dock and nobody the wiser.

She set hands on hips. "Him as I delivered to your door."

"Did you now?" Man One hitched up his belt and a good weight of belly. "You got a good imagination, girl."

Jones, that's Jones, damn great fool. Altair bristled and choked it down. Mondragon said forget his name in town; won't be a bigger fool and give them mine. "What I got," she said equably, "is a partner I brought here. You don't want to talk to me you can talk to the law that's all round this place."

Uh-uh. The eyes went opaque in a way that said wrong guess.

"So it ain'tthe law out there, then. That means Gallandry folk. Or it means Gallandry's got troubles." She folded her arms and planted her bare feet on their floor. "You got a damnsight more if you don't fetch up my partner.**

"I think," said Man Two, "you'd better go upstairs with us."

"I ain't going nowhere. You bring 'im here– hey!" The man reached and she moved, one jerk at her belt and the barrelhook was in her hand, meaning business. " Don'tyou try it, man. You get him down here or I'll carve up yourpartner here—hook him good, I will. You get up those stairs and you get my partner down here."

It was standoff. Man One, by the door, showed no enthusiasm to be the one hooked. Man Two backed out of range.

"Get him." Altair said. "Get him down here."

"What's it matter?" Man One said. His voice was high with panic.

"This is ridiculous," Man Two said, made an advance and snatched his hand out of range in a hurry.

"I ain't particular which, really," Altair said, and backed and kept her eye on both of them. "Now, you Gallan-drys—I'm guessing you're Gallandrys—you ain't of the Trade, but you ain't hightown either; maybe you seen up close what one of these things can do. I can hook up a barrel full to the brim and put 'er where I want—just where you hook it and how you sling. Want to see? One of you might weigh about the same."

Man Two walked over the desk, walked further still, taking himself out of her line of sight. She drew her knife left-handed, right hand to jerk a man into range and left hand to slice or stab.

"On the other hand," she said, "you go and split up like that, I'm going to have to stick him so's I can watch you."

"Hale," Man One said earnestly, against the door. "Hale, get up those damn stairs and get him down here. We don't want to get somebody hurt. He mighthave hired some boatman. Let him answer it."

There was a profound silence. Altair kept both of them in sight; but Man Two, the one he called Hale, had stopped his stalking.

4'Let's be sensible," Hale said. "You put that sticker and that hook away and you can come upstairs."

*'Let's be better than that. Let's you get him down here. He'll come, right ready. Friendof mine. If he won't I'll know you done him some harm, won't I?"

"Get him," Man One said. "Dammit, Hale, get up there."

Hale thought about it. "All right, " he said. "All right. Jon, you stay in front of that door."

Jon thought about that one too. And there was a fine sweat on his face.

"That's all right," Altair said as Hale opened the door and headed up a stairwell, "Jonny-lad, I got no hurry. You just don't move and I'll wait on my partner."

And how much else, Jones? That Hale, he'll either get Mondragon or he'll get a great lot of men and them with swords, and what do you do then, Jones? You're going to die here, Mondragon's going to be real sorry, but this is business, and a tumble and a night out on Dead Harbor don't mean a thing in the world's scales. Way the world runs, Jones. Sorry, Jones. You're about to die here, make part of Gallandry's foundations, you will, or you'll just wash right on down to the boneheap in the bottom of the harbor. Feed the fishes. Real stupid, Jones. What are you doing here? Why ain't you back at your boat?

Mama, I'm sorry. You got any suggestions?

Don't be here.

I wish I wasn't.

Her heart hammered against her ribs now that the imminent threat was abated. Steps creaked across the floor above. Her knees felt like water. She could maybe scare this man out of the way and get that door open before he came at her back—

But there were the bridges to pass. There were either Gallandrys or some other kind of watchers out there and it was the devil's own choice.

She grinned at Jonny-lad, her most engaging let's-be-friends kind of grin. The man looked nervous. "Hey," she said, "you think your partner's got any ideas about bringing back a whole mess of people? I sure hope not."

"Who are you?"

"Ask my partner. Really, I ain't the sort that goes breaking into places. But those fellows out there on the bridges don't look real inviting. You want me to fall into their hands with all Iknow?"

Jonny looked worried at that thought.

"Uhhh. They ain't Gallandry, are they? Who? Who would they be?"

Jonny kept his mouth shut.

"Well, I'll bet you could guess," Altair said. She held the knife up and studied it, and carefully put it away into its sheath, at which Jonny-lad looked at first worried and then a great deal easier. The sweat stood in beads on his brow. And someone was walking upstairs again, a heavier squeaking of beams. The walking reached the landing and headed down at speed. More than one set of footsteps, like half a dozen, down the last steps to the door and the light.

Hale came out that door and something russet came behind him down the steps, ahead of others—Lord, Mondragon, all in velvet breeches and a red cost and his pale hair all damp—

–Another of his damned baths.

Beside her, Jonny moved, abandoning defense of the door to the men with drawn swords that poured out of the stairwell behind Mondragon and into the room and around the edges of it. Altair stared, not at them, but at Mondragon, at that lordly creature he had become; at the sight she had imagined suddenly standing there in front of her. Men poured all about her, swords to deal with one canaler and her hook and her knife—it was altogether too much. She stood still, not wanting to be skewered, and one of the long swords came up and batted her hook-hand aside– stand still, that meant plainly. She stood, while Jonny in a fit of bravery came up, grabbed the hook and took it away from her. Fool. If she had decided to die right then Jonny-lad would have gone on his own men's blades and with her foot where it hurt. She stared straight at Mondragon, never quit staring, though one of the Gallandrys came up and grabbed her by the arm, and a second did, hard, so it cut off the blood.

"I want my clothes back," she said. "Hear me, partner?"

His eyes met hers. He stood there staring.

"They going to break my arm?" she asked. And never used his name. "I tell you you got a lot of—" —people outside this place—she started to say; and then went cold inside.

Lord, maybe they're his! Maybe I just spilled something that puts him in a lot of trouble.

"Let her go," Mondragon said sternly. "Jones, you keep your hands from that knife. Hear me?"

He held out his hand, expecting to be obeyed. The men holding her arms let go and the swords angled away.

"Damn nonsense," she said, and advanced on Jonny-lad. "Give me that. Give me that here."

"Give it to her,'* Mondragon said, and she put out a hand for her barrelhook. To her humiliation that hand was shaking. Badly.

"Give it here, damn you." She held the hand steady as she could. "Or some night I'll hang your guts over the—*'

"Jones!" Mondragon said. "Gallandry, give it to her. She's not going to use it."

The big man held it out. She took it and stuck it in her belt, point down in the split place made for it; and dusted herself off and walked over toward Mondragon, who turned his back and walked off through the door and up the stairs.

She trod after him. Behind her Hale was saying something about bolting the door; and armed men followed them up.

Canal-bottom, Altair thought glumly, climbing the old board stairs at Mondragon's back. Bone-pile down at Det-mouth. Ancestor-fools, I've done it, I've done it good, old Del and his wife're going to have my boat and the Det's going to have me before all's said and done.

O Lord, Mondragon, what areyou?

There was a door at the top of the stairs. The Gallandry man in the lead, one of the swordsmen, opened it ahead of Mondragon, walked in and put himself by it as Mondragon and the rest of them came in.

Altair walked out into the room—it was a large room with too little furniture to fill it, a few tables, most small, one huge one, a handful of spindly chairs, a yellowed map hung on the wall. And windows, window after window, each tall as three men, panes clouded with neglect. Sparse. Rich men could afford to waste so much room. She had never imagined it. She turned and put her hands in her waist and looked at Mondragon, who stood there with the Gallandry men at his back.

She walked as far as the window and looked out the cloudy glass. The Port Canal was outside. The balcony over on third-level Arden was empty except for a casual stroller. She could not see the second-level bridge. Blue sky showed over Arden's wooden spires. She glanced back at Mondragon. "Cozy. You can see everything from up here."

Give me a cue, Mondragon.

"What are you doing here?"

"Hey, I told you. You owe me."

He stood very still. Finally he walked over to one of the side tables, unstopped a fine crystal holder and tipped a bit of amber liquid into one glass and another. He brought them back and gave her one.

"This poison?" she asked, with him up close and able to pass her hints with his eyes. Dammit, I'm scared, Mondragon. Where are the sides in this?

"I thought your taste was whiskey."

She sipped. It went down like water and hit like fire. The pleasantry went down even better, a little warmth after the coldness downstairs. He walked away from her as footsteps sounded on the board stairs and Hale came puffing into the room. "My transportation," Mondragon said to them. He took a sip of his own glass, held it outward in a warding-gesture to the others. "I owe her money."

Damn you, Mondragon,

"And a few other things," Mondragon said. He took another sip, came back and handed the glass to her. "Here, finish it, Jones. Hale, I want to talk with you."