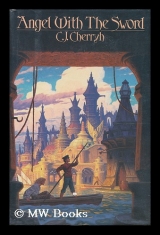

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

She had never told her how a woman dealt with getting a man onto her boat without having him get out of line and thinking he could take it over; and she had no idea at ail whether she was a fool for saying no when men made her offers. She didn't want to kill anybody, She didn't want to make a fatal mistake. She didn't know what the tight and wrong of things were—she knew well enough howit was to have a lover: a lot of things happened on barges right under the eye of God and everybody, on hot nights when the hidey was too hot. But her mother never had a man she ever saw. Her mother muttered ugly things when men shouted invitations. And Altair Jones pretended she was Retribution's son, not her daughter, as long as her mother lived. That was her mother's idea. And she did her bathing at night and wore loose clothes after she began to have breasts. She gave up some of the cautions after she showed too much, which was when she was twelve and after her mother died; but habits were hard, they were very hard. And she was a fool now. And scared.

And guilty, in a confused way, not sure whether it was a betrayal of her mother she contemplated, or something her mother would have looked at like her skimming up a struggling kitten and just hoping one would live, finally– Break your heart, her mother would say with a shake of her head. Poor thing's gone, Altair.

And she: Mama. Flatly. Never saying what ached inside her, snuffling back her tears when another thing died in her hands. So there was herself and her mother alone on the boat and never another living thing to touch. She saw cats in the rich houses, scampering through the balcony-gardens. She caught a feral cat once the year after her mother died, and it was so crazy it leapt into the Grand and swam for shore. She let it go; it had bitten her half a dozen times, and the bites went bad. She had imagined it would be soft to touch and would take to boat life. It would kitten and she would have kittens to sell to rich shore folk and do well for herself. But it was a shore creature. And her hand and her whole arm swelled. After that she had a chance to get a tame cat off a poleboatman—he wanted her, she wanted the cat. But in the end she got scared, mat we would get what he wanted and then maybe kill her and rob her: he was a back-canaler and maybe stole that cat from rich customers—who knew?

So she gave up on cats. Slowly gave up on chance-taking And men,

Till she got, in a confused way, step by step, to be a fool for something else floating down the canal.

Well, she said to herself this night—she talked to herself now and again, in her head, in her mother's voice—well, you finally got a man on your boat, didn't you, same as the damn kittens. Or maybe like that ingrate cat. And you got yourself a problem, don't you, Altair? What you going to do? Huh? Let him die?

He ain't any harm the way he is. Hasn't got a chance, the damn fool, without I do something.

So she stirred herself and she crawled into that shelter and heaved and hauled the blanket out from under him and over both of them, because she knew what it was when water-chill had gotten into one's bones. —"Tuck your feet up, fool, get all of you inside."

He moved. She tried to get her arms about his damp, cold body and keep the blanket snug, but he was too heavy to get an arm under; she pillowed his head on her arm and put herself up against him as close as she could get. The cold went from him to her, until the shivering started, great racking tremors that knotted him up for minutes on end until the last strength went out of him.

Then he was still.

That's the end of it, she thought. Out of strength. Fever comes now.

Rain-chill, winter-chill, river-chill: but there was a way to make a body warm. Her mother had done it for her; she had kept the sick kittens close against her heart, trying the same. And it was notthe same as her mother and the kittens; but it was dark inside the hidey; and he was clean, Ancestors knew, clean as old Det let anybody be; and more, he was dying, not going to tell anybody or snigger about it later.

It was selfish, more than anything, just for herself, scraps, which wouldn't hurt anything, and wouldn't go anywhere, since he was dying. The last living thing she had touched, really touched and held, was five years ago, when her mother was alive. So it was selfish; and perhaps every wicked act put the Retribution further away; but every good one brought it closer—so maybe what she did to make him easy balanced the wickedness in her mind.

Damn. It won't hurt. It might help.

She flung her arms up and wormed out of her sweater, undid her breeches and worked out of them too, till she could get her bare skin next to his full length—no great thrill: he was cold as a day-old fish. But she rubbed him till her arms ached and hugged him against her and bled the heat of her exertion into him, and did it again when she had caught her breath. He came to in the midst of this and started shivering again, which made him hard to hold on to, but she kept working—nothing sensual in the business at all: it was a fight that she kept up, chafe his skin till she had to rest and warm him with her sweat and do it again till finally either she was chilled or he was warm as she was. She gave a great sigh when she realized that; she put her arms about that human warmth and snuggled in without a twinge of guilt.

So she would dream about him after he had gone into the water and fish swam in and out the sockets of his eyes and picked the last little memory out of his brain who he had been, or why he had died; but he would not haunt her for it. Her mother had, for a while; until she came in a dream and cursed her gently the way she had when she snuffled over the kittens. Damn fool, Altair. Damn fool. Everything dies. Old Det gets it all. Love life and cuss death and be as good as you can.

She drew a great breath and gave a long sigh, relaxing further, inside as well as out. She made up memories for her bit of flotsam. He was a rich merchant's son, fallen on hard times. He had come downriver and met misfortune.

His father and his mother would send searchers. But they would be too late. They would find a trinket or two in the markets. His bones would He at the harbor bottom, under the keels of the moving ships. She would stand on the quay and watch the fine foreigners come ashore and she would hold the secret they wanted, a little canalrat would hold the secret all to herself and watch them in their fine clothes and their jewels offering rewards for the recovery of this rich man.

But he had come to her with never a thing, and she could not prove her claim to rescue. So there was no good to tell; and dangerous anyway, to meddle in the affairs of rich merchants. There would be the smugglers and the brigands and the gangs after the rich men left. Theywere the law on the river and in the harbor and in the canals of Merovingen. And the collection of fish-picked bones down there in the mire of the Det was already considerable. She had no wish to join them. Hence her silence.

Their ship would steam back upriver, the rich relatives uncomforted.

She held him close and let him sleep, so that the life would go out of him that gentle way the way it went out of drowning kittens and birds that fell in the winter ice, just quietly, on a breath. She would roll him overboard in the morning, slip, splash. Her secret. The closest secret almost-event in her life, when she had almostsaved a rich man's son and almosthad a lover.

Somewhen she fell asleep and woke in an unfamiliar tangle of male limbs. A gentle snoring had waked her. The snoring stopped. He had a hand on her breast—her knee was tucked up against him somewhere embarrassing. She held still. He shifted a leg and nestled closer there in the sightless black of the shelter, his head burrowed against her bare shoulder. Then she lay there with her heart pounding, thinking whether to get up or not to get up, and since she had to wonder about it, it seemed all too much effort to escape a man who was, well, if not dead, at least not in a way to make himself a nuisance by morning. He was only warm, and different, and temporarily all her own in a way no one but her mother had ever been.

Merovingen was out to take, that was all: body, soul, life and property if a woman was once fool enough to give up that line that said No; and fool enough ever to share that little portion of the world that a pole and a boathook and the habit of sleeping lightly could keep solitary and safe from men bent on mischief and murder.

So, well—once. Maybe once, for a few days when he got well, if he got well; and thenput him off somewhere. On her terms. And let him do what was natural for a man the gangs were after, which was get on the First boat up the

Det and keep going. Far away from Merovingen. So he would never talk, one way or the other. So he was a safe kind of lover. She mulled that over in her mind and came to that conclusion. He had no grudge against her. He had every motive to stay out of sight and let her get him to some destination; and if he looked like he had designs, well, then, she would pick that up: she was good at reading intentions. Then it was the boathook for him—or she would find out who his enemies were and give him to them if he looked to turn ugly. If he made any threat to take her boat.

Now that she had come this far she suddenly knew all sorts of ways to get a man off her boat. Like wait till he was asleep and do for him. Or hail a fellow like One-Eye Mergeser and start a fight; or a dozen strategems she could think of, if things went wrong.

But they would not. He was not like that. He had a gentle way about him, even if he was asleep. He would be grateful, for a few days, in the strange nowhen that had cast this pretty bit of flotsam up onto her boat.

Old Del gave a gift, that was what.

A lover from a past life?

Only if the Revenantists were right.

She doubted it.

One got what one took in this life. Her mother told her so.

Chapter 2

SHE waked again in that close, unfamiliar warmth– chagrined: she had not meant to sleep so long or so soundly. But her passenger was still warm without feeling fever-warm; healthily sweating, in fact, with the closeness, as the first stir of activity came in the dark outside the hidey, and some coaster out in the harbor churned up a wake with its engine as it beat along toward the shallow channel to the sea. Getting an early start on the world.

The sweaty warmth against her stirred, burrowed closer and snuggled down with a sigh as if a woman's arms were part of his ordinary sleep. Or he was awake and damn well knew where his hands and his face were. She wriggled aside and out of the shelter, searching up her clothes as she went; and sat outside with the fresh wind chilling her skin and the gentle rocking of the boat all part of a strange, still-black morning, there beneath the wharves.

She ran a hand through her hair, found it itchy and none so nice. Her clothes were not as bad: she had washed them three days gone; but she was sweated and hated to get into them. She never minded a few days unbathed: weather sometimes set in with a chill that discouraged bathing, and she was alone on her boat; in fact she cultivated a certain griminess—too clean and a woman looked like she was looking, which invited all sorts of trouble. She made a spitting sound in self-disgust, not at the dirt, but at the silliness that made her care for a day; for once—well, not to be thought dirty. Hewas not; he was clean-shaven, without even a stubble, she recalled, until this morning when she had felt his chin against her shoulder—

(So he went fresh-shaven to his murder—A woman? Had he been meeting with some lover? But those black-hooded skulkers had had no look of someone's outraged kinfolk.)

–a fastidious man, at least. If there had been dirt on him the canal had left only its own fishy stink, which passed for clean in Merovingen-below. So could she be– fastidious when she wanted to be.

She had soap. She found the little cake of lye and lard and slipped over the side of the boat in the safe halflight before dawn, bobbed up again treading water in the gentle slap and toss of the chop. No danger of drift. She scrubbed her hair not once but twice and three times, and scrubbed herself with the white froth floating away on the waters beneath the pilings, while the sun came up enough to give a little rust color to the peeling paint of the boat-side.

And just as she surfaced from her final ducking she found herself staring up at a pale, very live face peering over the rim of the boat.

So there she was, with a naked man on her boat above her and herself at decided disadvantage down in the cold water. "Get back," she said, sharp and hostile. "Back." Thinking if he should turn surly there were still ways, and the knife and the hook for him, and the bones at the bottom of the bay. She glared up at him and bobbed there. Flung a splash of water up at him. "Back."

That seemed to wake his wits. He moved backward in some haste and retreated up a few feet toward the bow as she glared at him, elbows on the rim. He did not look threatening, rather dazed as a man might be who came back from the dead stark naked on a crisp morning.

She pitched the soap into its bucket and gave him a hard, misgiving look just to be sure he stayed put. He had settled as modestly as he could, knee tucked up and sideways. So she glared again, gave one great duck and heave and came up over the edge, slithered aboard in a wash of water and sat down and snatched after her clothes, dropped them all into her lap fast, and struggled into her sweater without a pause to dry her hair or to towel off. Pants next, quickly. She got up and hauled, not fool enough to turn her back in modesty. She just fixed him with her eye and glared to show she was in no way embarrassed and that he had only tentative welcome on her boat.

He stared. Not like the dirty boys that spied on the barges from the bridges; and hooted and called down insults, imagining they saw more than they did. He stared as if a naked woman was a holy and unexpected wonder to him, while the boat swayed in the chop a passing coaster kicked up; he sat leaning on his hands and swaying too, with the boat-motion.

He was so damn nice-looking. Her heart did a curious little quickening and she felt—warm. And oddly safe and unembarrassed and expansively content with what she had done. Reckless. Ancestors, she was not wont to be so soft-headed. But maybe it was natural that people took chances when they were in love. Like shooting the Det Bore when it came, though it tipped boats and took the unskilled; it was that kind of feeling, heart thumping, everything aslide and uncertain and by-the-Ancestors alive.

"My name's Jones," she said. "Altair Jones. This is my boat.*' And when he did not respond to that: "I've decided," she said, "you can be my lover."

He blinked and got a wary look, slid a bit back till his back hit the wood of the far side. In one heartbeat she was dismayed; in the next felt the fool; and in the third she knew for certain that she was. A man had a right to say no. She never heard of one who was inclined to, unless– Maybe he liked men, that was all. Which was a waste. But he was very pretty. Maybe too much so. She gazed at him with regret.

"Well, you don't have to," she said sullenly. She pulled out her other breeches from the side of the hidey, the over-size ones; and pulled out a sweater (she had three, all twice the size she needed); and flung them both at him. "Try those."

He blinked and let them lie there on the slats.

"You want 'em in the bilge, dammit?"

He gathered them up hi one reach and never made another move. His face showed all white in the tentative dawn, his fair hair dried and curling. Another ship thumped to life, a fishing boat sending out a wake as it passed; and the water lapped and splashed against the pilings.

"You mute?"

He moved his head. No.

She squatted and rummaged the other little packet she had there by the hidey, unstopped a jug and took a bit of bread and cheese out of their wrapper. Offered it toward him. He shook his head.

Fool. Rushing at him like that. Man's been hit over the head, swallowed all that water. Offer him to be his lover, and him with a cracked skull. Damn silly, Jones. Try to use the brain you got. Probably thinks you're crazy. "You sick at your stomach, huh?"

A nod.

"Head hurt?"

A nod.

"You got a voice?"

"What am I doing here?"

Not what'm'i'doin'ere. Clear and pure as a voice could speak it, a quiet, immaculate voice that brought her and her outheld hand to a frozen stop.

She heard that kind of accent at distance, at the distance of lordly voices drifting from the heights of bridges and the insides of buildings and the other side of grilled doorways.

"I fished you out of the canal, that's what. You got a lump on your skull and you got that water in you. It'll rot your gut out." She came closer and squatted down again and offered the bottle at arm's-length, bare toes tensing on the slats against the heave of the boat. "Drink. Whiskey's best cure I know. Take it."

He took it and downed a sip with a grimace. He drank carefully. Grimaced and swallowed, once, twice, and handed it back, wiping tears from his eyes. He began to shiver then, as she stopped the bottle. "Get some clothes on," she said. "Want people to stare? I got a reputation to think of."

Another blink. Maybe, she thought, the blow to the head had addled his wits. She waved a hand at him, move, move, and in a rush of remorse for the mistakes she had made: "Hey, I'll boil you up some tea. Sugar'n all. Go get warm."

Sugarcost dear. She could have bit her tongue for that impulse she threw atop it all. A lover was one thing; sugar cost money. Sugar, she had a tiny lump of and had hoarded it for some special need, months and months. But he was it, she decided, he was that special need, plain and simple, and maybe it would be what he needed, ease his poor stomach and put a little life in him.

So she got out a match and the oil stove, an old metal oil can, with the bottom of an old lamp; set it up on the slats of the well and carefully boiled up water in one of two metal bowls she had. She dusted tea into it; then (with a wince) the precious sugar. Took a sip herself out of self-indulgence, then edged over to her passenger. "Here. Don't you spill it."

He had worked the loose breeches on, with a perilous wobble when he essayed a rise to his knees; and lastly the baggy blue sweater—his wide shoulders and long arms were almost too much for it. He sat down again of a sudden on the bare slats of the well and for a moment swayed to the motion of the boat. But he took the bowl and drank in gingerly sips, there in the full dawn. All pale and scratched up and with a morning stubble on his beautiful face, and a swollen cut on his lip where they must have hit him. He drank; and she sat there on her haunches with her hands tucked up against her warm skin under her own sweater and thought and thought.

He wasa rich man's son.

And there were those who wanted him dead, who might not take kindly to her interference. They might be bullyboys and no great trouble; a chance meeting and a mugging and a quick toss of a body into the canals. That was no great novelty hereabouts, and bully boys of their ilk were secure in their very numbers and facelessness—until they crossed a canaler.

On the other hand—there were other possibilities to consider. Like him having personal enemies. Like uptown trouble. Like trouble that could wash down on Altair Jones and her little boat like the Det in flood, and her bones would settle down amongst the collection at the bottom of the bay. Rich man's trouble.

Lover, indeed. Thatwas why he was repulsed by her. He was too high for her, that was all. Probably he had never thought of sharing a canalrat's bed. Might get bugs. She scowled over that thought and reckoned she need not be personallyoffended at the turn-down. So she was seventeen and he was the first man she ever asked. So she started a shade high, that was all. Woman could always try. And he was merchandise. This was money she was looking at, by the Ancestors, she had in her hands the most valuable bit of flotsam she had ever gathered out of the Det. And perhaps—she looked curiously at that fine, lost figure that sipped its tea and looked so out of place against the bare old boards of her boat—perhaps hewould just as soon see her sunk to the depths the minute he was safe with his own kind. Handsome did not mean fair-minded. Or generous. That pretty face and that worried look of his might mask a thorough-going villain.

Damn. He probably never even knew what that sugar was worth, probably had it every day, heaped and piled on his food.

There had to be a way to figure out what he was worth and where. He was wobbly, but not weak enough to handle carelessly. He showed signs of increasing steadiness, in fact, which made her think of her knife and hook under the rag-pile, and the boathook and the pole, which she could wield a lot more deftly than a landsman would think. And there was a paper of blueangel, which was for the fever; but the whole paper in a man's tea and he would be in no shape to protest being rolled overboard and in even less shape to swim.

Not that she wanted to do these things. If he was worth something, that might well mean collecting from his enemies, and Lord, she did not want to do that.

Not that, and not any deal with the damn Megarys either, who dealt in disappear-able live bodies and sold them to outbound ships and upriver slavers. The trade went on. The law knew. Every canaler knew. But not a sick cat would she trade to the Megarys.

Not to say he might not be a scoundrel after all and deserving of all he got.

Lord, he was so pretty. He was so damn pretty. He looked up from his tea-sipping while she was looking at him and thinking that, so she was caught with her guard down.

"You got a name?" she asked, sitting on the edge of the halfdeck and finger-combing her damp hair.

"Tom," he said.

It was certainly more than Tom. It was Tom-something. Something-Thomas-something, him being a high towner; so he was not willing to hand out his whole name to her. He was not all trusting, then. Not by a far ways.

"Tom. That all of it?" She reached for the empty tea-bowl. "You got a home?"

He did not answer that either. Not right away. "No."

"Live with the fishes, do you? Just follow the tides and dine on minnows and seaweed. Well, I don't doubt you'll be falling back in, then, having drunk up my tea and all."

She had not meant it for a threat. But he had a wary look when she said back in, and she saw he took it that way.

"Look, six bullylads threw you into the canal last night and I fished you out, having no better sense. Now if you've got any particular place you'd like to go, I c'n maybe get you there."

"I—" Long silence then. He sat and stared and a passing boat rocked the skip against the pilings.

"Who's after you?"

A blink. No more. Then: "My name's Mondragon. Thomas Mondragon.''

She ran that through her memory. There was no Mondragon she knew of. That meant a lie or that meant up-river, Soghon. Remote, hostile Nev Hettek, even, Farmer he certainly was not. She felt cold despite the sweater and the thick trousers. Money seemed a little farther away than it had been; and not just to Nev Hettek and back. She put her hands on her knees and drew a deep breath.

"You got a place to go?"

Silence.

"Well, I'll tell you this, Mondragon. Whatever your name is. You better wrap up real good. You better get yourself back in that hidey and stay low, because it's getting light and I don't want folk seeing you; and you better think real hard what I'm going to do with you, because you got one day, and if you ain't got it by morning I'm going to come back up here to the harbor and let you off and you can just find your own way uptown."

"Where are we going?"

"Well. Someone's awake. You got a place in mind? You got a place up there on the Rock? Rimmon Isle?" Rimmon was a haven for foreigners among the rich. "Got friends?"

Blink. A long moment he sat there, passed a hand over the back of his head. Stared at her.

"Well?"

Wits addled for sure, she reckoned. He looked dazed. Lost. It was too good to be an act.

"Crack on the head'll do that for you," she muttered, "Damn. Damn mess. Look, Tom-whoever. Get yourself down under that hidey there and tuck yourself up and sleep it off, huh?" She got up on the deck, tugged on the mooring rope and slipped it, then walked back aft to throw up the engine cover. She gave it a crank. Gave it another while they drifted free beneath the pier.

"Where are we going?"

"No matter to you. Lord! don't you fall in—"

He was on his feet and the boat bumped a piling. He went down on one knee, caught himself and sat down hard on his backside.

"Brain's kind of shook," she said, and adjusted the choke. She gave the engine yet another crank. It gave a hollow cough. A fourth try and holding the choke against the suction did it. The engine tanked away, churning up a white surge on the dark water. She loosed the hook on the long tiller and put the holding pin in to get it in action before they hit another piling. Dropped the rudder and set its pin. "Go on, get under cover. If we meet anybody, hear, if you hear me talk, whatever, you don't put that blond head of yours out of that hidey."

The boat tunked along, moving slowly in the chop beneath the deserted piers. Not wasting fuel. She put the tiller farther over and kept her course under the pilings, which was the quietest way to move. Mondragon got down on his knees and slid backward into the hidey under her feet, disappearing from her vantage.

"Thanks is fine," she said above the engine-noise, as the boat labored its way along under the pilings, eating up fuel that cost nearly as dear as the sugar. "I'm glad you're so grateful. That's real nice."

After a moment a hand caught hold of the deck-edge; an arm followed, and he put his head up. "Thanks," he said.

"Doing what I say is best," It was her mother's line. She delivered it sternly and with all the righteousness her mother had ever used. "What if them bullyboys get sight of you, huh, and come after me? Maybe you don't remember. Maybe you need time to get your brain unscrambled, huh? All right. I'll hide you out that long. You eat my food. You sleep in the hidey. You damn well do what I say. Hear? Now get back in there."

He let go all at once and vanished.

She held onto the tiller and drew a great amazed breath.

So. She said and this rich man, this handsome uptowner, ducked and did as he was told. She drew yet another breath, with the timbers passing in insane perspective toward dawnlit brown water. She was in control of things on this her deck, this morning. She swung the tiller as the boat passed from under the New Wharves and headed under the Rimmon Isle bridges, a dark, dark passage toward the dawn-lit water of the Old Harbor.

It was open running after that—shallow water in places, so a body could go aground and maybe hurt a boat doing it, if a body did not look sharp and know the currents that swept the Dead Harbor, at least in principle, Knowing them thoroughly was a matter of sailing the harbor every day; which some did—the harbor-dwellers were out here, looking like tiny floating islands on their rag-canopied rafts. Some were pathetic, a lot old, riverfolk just gone beyond their prime and down on their luck, surviving till the end. Some were not old; some were downright dangerous. A lot of crazy had come down from the Ancestors, curse them; and the really lunatic haunted the marshes and ventured out on the Rim in numbers. Of those, the pathetic ones died and the dangerous ones flourished, having no more scruples than a razorfin and about as much hesitation when it came to prey. It was evolution at work. The cannycrazy ones survived best, and occasionally the Governor declared a cleanup, and the law and the sporting uptowners came down and scoured the Rim until they had routed out the current crop.

Naturally the canny-crazies took to rafts and most got away, and laid low for a few days, to return again.

So it was wise to go wary crossing the water out here, steer well clear of others, and when it came to a harborage on the Rim in this season, a body just coasted along looking for an unoccupied niche, something with good visibility and a bit of beach.

Mondragon put his head out again, up over the edge of the hidey.

"You can come out," Altair said over the low mutter of the engine and the slap of the water. "Just as well someone does see you out here." He looked doubtfully leftward, where the bleak rocky shore of the Rim showed nothing but shallow anchorages and floating garbage that even the fish disdained. "Rough place," she said. "Just as soon have folks see I got a man with me. Understand?"

He gripped the edge of the halfdeck and slid out, kneeling there after with his arms on the deck surface. He still looked a little dazed.

"Look lively. I bring her in and you get up for'ard and step off with that bow rope and just give her a pull. You strong enough to do that?"

"Where are we?"

"You ain't local for sure."

No answer.

"This is the Rim. Old seawall, most natural, some the Ancestors built. Back there—" She waved an arm off toward the open water. "That dark spot in the water is the Ghost Fleet. And further back, on that shore, that's the Dead Wharf; and over from it's the marsh; and that great hazy flat out there's the old port."

He twisted about to see, then got to his knees and got up, wobbling this way and that,

He sat down, thump! on the slats, with a wild wave of his arms and a quick catch of one hand against the deck.

"Damn, you're a lot of help."

He twisted round with a scowl– nother gentle bewildered fool; it was for a moment a hard-planed face that looked at her, looking somehow older and more dangerous. Then the planes relaxed. The fool was back.