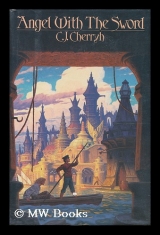

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

A hand came up over their rim, the boat felt it– " Mondragon! Boarder!"

He saw it, handled the boathook with a right smart reverse and the boarder went back where he came from; but they were too near, they were coming far too close, men were pouring off the second raft to come at them through the shallows—She fired; and the surge of bodies went every which way. Screams.

An arm and a head came up over the deckrim near her. " Aft, Mondragon! Ware aft!" She saved her bullet for the raft they were passing. Let it off to save them from the hooks. The man was climbing up the portside by her, one fast surge and he was rising—" Mondragon!"

The pole appeared out of nowhere and the man went under. The screw hit something: she felt the slight resistance; but the boat tunked on, the third raft beside them now, hooks reaching, bodies pouring off the raft. She fired. Mondragon yelled and poles cracked together.

A hook snagged the wood. " Ware hook!" she screamed, slewed the tiller; and the boat kept moving; the whack-whack-whack of poles was sharp and keen over the scream ing and the engine noise. She saw open water, drove for it, as her own position came too near the hooks. She could see feral men, their spiky hair, their eyes agleam and their mouths howling in the starlight, the whole mass moving and reaching like some bad dream. One shot left. One shot. She clung to the tiller and kept judging that distance.

The bottom scraped sand on starboard. Her heart jumped. The scrape stopped; the boat went on, scraped again, silent in the deafening yells to port side, the reach of hooks Mondragon fended as he could. Blood ran on him. He staggered to a crack against the pole, caught his balance and swung a hard, sweeping blow that took a crazy off. More blows came back; and then they were passing the corner, hewas in the clear, and the hooks reached for her, men jumped after the boat; but they were late. The boat chugged on, the water between them widened, and Altair heaved the tiller over to take them out into the harbor.

God, they could have had bows. One of them could have had a gun. She was shaking.

I killed five people. Maybe a dozen. Her whole arm ached. She remembered the man the screw had chopped and tried not to remember. Mondragon was looking at her, sitting on the deckrim, agleam with sweat in the starlight. The boathook lay aslant over side and deckrim, under his hand.

Altair set the tiller and squatted down and opened the ammunition box. She broke the old gun, rammed five new cartridges in and clicked the cylinder into place again. Her mother always told her not to fire the last round—"You never empty your gun, hear, you reload on five; you finish a fight, you damn well better have one bullet left." Why was not a question you asked Retribution Jones. You just said Yes, mama, and you did it. And she had. Her hands shook when she put the gun away, but Retribution's slim tanned fingers had handled that old gun like it was a metal part of them. Her whole body shook. She felt her mother crack her one for that, could feelthe sting on her ear; and she sucked a breath and sobered up and remembered she was sitting half naked on her deck and the engine was running, drinking up precious fuel.

Damn. Damn. It was no time to cruise the harbor; if they spent fuel, they spent it getting acrossthe harbor, which spent it the way she had planned. She had no money to buy more. She had about enough for Moghi's barrels without taking a loan. And she had two bottles of whiskey and a handful of flour and a paper of tea and two mouths to feed. Damn, damn, damn. She throttled back to a fuel-saving speed; they were crossing on the backflow of the tide and they would feel it about the time they crossed the Rimwash current: it would eat fuel like a drunk takes whiskey. They would make it on what was in the tank. And then she would be about flat.

She looked at Mondragon, who looked at her. Not awkward. No. She remembered him in motion, not well-skilled with that pole, but he took to it fast, he found his balance, he hadn't gotten snagged or let them get past his guard.

"Didn't know you had a gun," he said finally. His breath still came hard.

"Don't like to use it." As if she did it now and again. Better he believe that, and not get ideas. She stood up with a hand on the tiller for balance. The wind was cold on her sweat. She gave her head a shake and drew the wind into her nostrils as she scanned the water ahead. City lights were mostly out now, only a couple of sparks snowing; and the way was clean—give or take the passage under the pillars of the Rimmon Isle bridges. Thatcould be a sticky spot at night.

She thought about it more and shut the engine down all the way.

"Where are we going?" he asked.

"Dunno." And then because she wanted to appear to have the answers: "Had enough trouble tonight. I'm too tired to pole her through the bridges and I sure as hell don't want to tie up there; we had enough crazies tonight."

"Is that what they were?"

"Crazies or rafters, small difference with some." She drew in another large breath, blotted the killing from her mind and drank in a certain pride. Herboat. Hersay, how it ran. She knew what she was doing and he knew she knew. She saw her mother, saw Retribution Jones handling that tiller in her earliest memories, sunlight on her face and those fine hands of hers so sure of what they did, the way she walked in those bright years, like the world had better move out of her way.

She hitched up her slipping towel and hopped off her halfdeck into the well, turned to Mondragon where he sat on the deck rim. "They got you a couple of times."

"Broke the skin." He stood up and caught her arms. "Damn, girl—"

She shook his hands off right quick. " Jones. Call me Jones."

"Jones." He stood there in the starlight and found nothing else to say.

Neither did she. The boat had lost most of its way, drifting with the chop.

"I got some salve," she said. And because she wanted to be clean again, sweat-slick and feeling the touch of the crazies still lingering: "I'm going to take a bath."

He said nothing. She dropped the towel, turned and stepped off the side, a straight drop.

Water shocked beside her, a gentle drift of bubbles against her skin as another body arrived. He found her, wrapped his arms around her. Damn fool, she thought, and in a moment of panic—Is he trying to drown me, a murderer after all, he wants the boat—?

Evidently not. She surfaced with him, rolled over in a sidestroke and felt him swimming at her back, stroke for stroke. She blinked back to sanity then, broke stroke and trod water. "Damn, we trying to lose the boat?" She saw it farther away and launched out for it with strong driving strokes,

He reached it first, none so far—held to the side and waited for her.

They almost lost it again when she caught up.

"Jones," he said in a way no one had ever said that word before. "Oh, Jones." And then they had to catch the boat a second time.

Chapter 3

MORNING was for slow waking; a little more of what they had done before under the stars on the halfdeck. And finally another swim: that was four baths in two days and Altair was amazed at herself. She washed her clothes too, soaped them up good and left them on the tiller to dry a bit in the wind, and he washed his, and they sat having breakfast in the afternoon wrapped in towels and letting the wind dry their hair. Hers went straight. His went curly and fine as pale silk. He was beautiful, every move he made was beautiful, the way the muscles stood when he reached for a bit of bread, the way the sun hit his face and turned his hair to light. She ate and stared at him every chance she got. And sighed.

"Where do we go now?" he asked finally, and she shrugged, not wanting to talk about it. He took that for his answer, it seemed.

But when she had put the breakfast dishes away, when she stood up and saw the rafters out floating like little islands on the Dead Harbor rim—she remembered the night and remembered what it might be like to try to find their way around the rim of the Dead Harbor, poling because they would be out of fuel. And that decided her. She sighed again and bent and took her pants from their hanging-spot over the tiller, and pulled them on. And the sweater.

"They're still wet, aren't they?" Mondragon asked, still wearing his towel, standing down in the well.

"We got to get moving is what, You want to tell me where?"

"Do we have some hurry?"

"Mondragon." She came and sat down where there was no need to yell it over the water-sound, on the declaim in front of him. "We go out there to the Rim again, that takes all the fuel I got. And poling back from there's a bitch. Through the rafters and the crazies." She hooked a thumb back toward the town, toward the low hazy hump of Rimmon Isle. "We got enough to get to the shallows under the Rimmon bridges. And I can pole her where you want to go after that, unless it's out in the bay. But I'm about out of everything except whiskey, I got a living to make, and the current here's going to generally drift us further and further toward me Ghost Fleet, which ain't a good place: crazies hang out there, 'gainst the sandbar, and it's opposite to Rimmon and I got only so much fuel to get us back; I been watching the drift. So all in all, I think you better tell me where you want to go, because where I'm going is back in the canals and I think you got reason not to want to do that. I reckon you've got a riverboat you'd like to get to, or maybe that Falkenaer ship. I can't pole you to the Det-landing, she's too deep, but I can set you out right at the dike, there's stairs at Harbormouth; and you just go up and over and right down the dike to the Det-pier and down again, easy walk. Best I can do."

He was quiet a moment. He looked down at the slats and up again, arms folded. "Let me out in the town," he said.

Her heart did a skip-beat and tightened up again. "You going to go hunt up trouble? Once in the canal not enough for you. Tell me where they'll throw you next, I'll keep my boat waiting."

He looked down at her with a tightening of the mouth. It turned into a wry smile "Stay out of my business"

"Right. Sure. Get your clothes on."

"Jones—" He took her face between his hands and made her look up at him. "I like you a lot, Jones."

That hurt. She drew a great breath and it felt like something would break. "Hey, you get me a kid, man, I'll kill you." Had her mother been that stupid? Was that how shehad happened into the world? One time her mother let her guard down and liked a man like Mondragon? Or was it just some ugly accident or a rape somewhere her mother had lost a fight? She could not imagine her mother losing.

He brushed her hair back, kept looking at her. And let her go finally and skipped up onto the halfdeck to get his own clothes. When had he found his legs? When had he learned to move on the boat? Last night when he had to, when he stood there wielding that boathook with skill that grew by the minute—

–blade fighter, she thought. Fencer. Hightowner. They came in all types. Street rowdies. Duelists. The hightown had those too—some of them very rich. Some of them who would talk in that silk-soft kind of voice and not know spit about not dipping a iron skillet in the water or grabbing a prickleback round the fins.

He knew about deathangel spines all right. He knew how to take care of a good knife.

He had had no bad scars till the boathook caught him in the shoulder last night and he would carry that for the rest of his life—not a deep one, but wide as that blunt hook could make it. (He'll remember me, won't he? Rest of his life. Everytime some soft uptown woman asks about that scar.)

He knew how to fight. Which meant he was no easy prey for those black-cloaked devils on the bridge. How had they got him, anyway?

The knot was on the back of his head, that was what.

He pulled his pants on, wet around the seams as they would be. Sun would go on drying them: no worry of taking fever.

Altair sighed again, men bent down beside the hidey and swept up her well-worn cap, pulled it on hard against the wind, and winced and suffered a jolt of the heart: there was a knot on the back of her skull too, right where the band touched. She settled the cap a little back of that, tilted on her head, jammed it down and skipped up onto the halfdeck.

The traitor engine started on the third crank, regular as could be.

* * *

She shut the engine down finally with maybe enough fuel left for a startup, maybe a little more—"Never you run nothing down to empty." Her mother had dinned that into her. "You plan so's you don't. You lay yourself open and Murfy'll get you, sure he will." Even Adventists believed in Murfy. He was a saint in the Janist pantheon. "You gave old Murfy a chance," her mother would say when she slipped up. "I tell you, you can't give chances away. You need all you got."

She hauled the rudder up, pulled the tiller-pin and let the bar fall to be hooked stationary to the engine-box. So the boat coasted toward the tall pilings between the dike and Rimmon Isle on the way they had left; and she gauged it right. The bow skimmed over shallow water, the line that was dark and not green, without a pole to push it; and while it was crossing that line she unshipped the pole and walked to the front of the halfdeck to put it in, walking it along on starboard; then crossed over and walked it on port, while Mondragon stood out of her way in the well.

"Can I help with that?"

"Hell, no! You'd be clinging to that pole and the boat off on her own. I seen many a beginner go right off the deck."

Back to starboard. She was flatly showing off, keeping the boat moving at a reckless clip, making it look easy as it headed for the pilings. Moving cheered her. His bright face in the sunlight did, for what time she still had his company. Not raining on tomorrow, Retribution Jones would say. Or the afternoon. Her bare feet were sure on the deck. Not hard shoves. Deft ones. At the right time. "This kind of boat's called a skip, dunno why. Skip's got a halfdeck and an engine and she's bigger'n any poleboat. Moves real sweet in the water if you know her tricks; any boat's got'em. She's engine-heavy and she slews bad, but you can use that on the turns, if you know what to do with the pole. She starts slow and she stops the same way when she's loaded; then you use the currents much as you can—canals have 'em, same as the harbor or old Det himself, and some of 'em's fierce. You plan way ahead. You don't feel that load right, she can ram a wall or another boat and tip everybody right over if her load shifts."

They were coming up on the pilings. Mondragon turned as the shadow fell on them, and staggered when he faced that perspective, the black maze of pillars that was coming fast. "Jones—"

"I know my way.'* She worked it fast, this side and that. "Better be right, hey?"

They shot in amongst the pilings, into the dark of the bridges that linked the city to Rimmon Isle and its fortified mansions. Light gleamed hurting-bright at the end, which was the harbor, and the pilings rushed by them. Mondragon stood in silhouette against that light.

Trip through hell. Or purgatory.

She had her line planned. No way the boat was going to skew from it, except at the end when they hit the inflow from the harbor. They kited out into the dazzling light, the water throwing it back off its surface and swirling brown into the lucent jade of the deep bay.

"Ware!" she sang out, meaning she was about to turn, and bottomed the pole and swung the bow over so smartly and shoved her off so deftly there was never a jolt. Mondragon kept his footing with a little stagger, turned and looked up at her as if he thought that was a trick designed to unsettle him.

"Hey, you got your legs, Mondragon." She grinned at him. "You'll roll like a proper canaler when you walk ashore."

"I don't drown easy, Jones."

She grinned wider. A light sweat stood on her and the breeze cooled her skin. The wind smelled of waterfront and old wood, which was the smell of Merovingen and its harbor alike. They went into the dark again, under another pier. An idle boat was tied up there down the way, likely a fisher cursing the luck that kept him in for repair. The sound of hammering came to her, and echoed off the docks and the dikes. They slowed: they had lost a little way in the turn and she did not pick it up again. She just headed for the series of bright-dark water stripes ahead, between the series of water-blackened pilings.

"Where you going in town, Mondragon?" she asked. "You didn't tell me that."

He turned again and looked up at her. Sun hit his face as they skimmed into the light again, and he grimaced and shaded his eyes. "Jones, forget my name. Don't talk it around, just say you had a passenger, say my name was– whatever's common here."

"You won't pass for a Hafiz or a Gossen, not with that complexion. You got a burn, you know that?"

He took a reflexive look at his arm, which was reddened, raised it to shade his eyes again. "Believe me. Forget that name."

"Why'd you tell me?"

A moment's silence. He stood there with the hand up and let it fall again as they headed under another pier and into deep shadow. "Must have been the rap on the head," he said, quieter.

"You got real troubles. You sure you don't want me to take you to the Det-landing?"

"I'm sure."

Mondragon—She stopped herself short of the name, wiped it out of her reflexes. "You want my help?" Fool! "You want me to keep you under cover awhile?" She hoped suddenly. She took the chance the way she took the chance with the pilings, because she knew the maze, she knew the ways, she was adept at surviving and took some chances because it was style. It was—whatever made life worth having. He was one. "I could do that. Do it easy."

He stood there with a look on his face that said it tempted him. With a look in his eyes that said he was thinking. "No," he said. "No, you better not."

"You being a fool?"

"No."

"You already got a cracked skull. You going to go back where they can get another swing at it? Second time they'll split it. Second time I might not be there to pull you out."

"Hey, you going to take me for another night out there with the crazies?"

Her accent on his tongue; it was deft, too. She grinned in spite of herself. "Not bad. Not bad hit."

"Jones—" The light came back and he squinted. "Jones—thanks."

They had reached the Mouth, where the dike towered up before them and the warehouses of Ramseyhead were at their left. Her bare feet hit the deck in short, quick strides as she positioned for the turn, touched the pole on that side and drove them hard for the Mouth; a little hard work now: the Mouth was always a hard crossing, where some of the sewer effluent created a wash. She heard that thanksand there was no time to handle it, just the boat, just that quick, hard rhythm of her life, which went on before him and would go on after him. And maybe there was nothing worth saying.

Something stupid like Come back?

He was going to end up in the canal again; or he was going to take off those canaler's rags and dress himself in hightowners' velvet and silk and walk the high bridges with no more interest in the boats that plied the shadows than he had in the vermin and the feral cats that conducted their war in Merovingen's sinks and bowels. Velvet and silk. Not his back on bare boards and a dirty blanket. Whether he was one of the shady sort of hightowner or something else—he had no business with her.

Unless he maybe wanted a bit of freight moved.

Or a cheap night.

He had turned his back again, the ridiculous too-large breeches having slipped a bit—Lord and Ancestors, he'll be a fine sight where he's bound. They jump him, the damn pants will trip him. Maybe old Kilim's got a pair he'd trade for.

What am I thinking of? Like I got time? Like he's staying? He'll throw those damn things in the canal when he's uptown and back with his own. No, he'll have some servant do it.

Can't be out of the gangs. He can't. Not with that way he talks. Not the way he talks when he's got his hands on me, not then–couldn't talk fine words then except they come natural as breathing. I can't open my mouth, I can't think pretty, I wish I could. Wish I could.

She smiled and shoved the pole this side and that as the towering black wall of the dike glided past. As they went under Harbor Bridge and headed onto the Grand. Mondragon turned round and hitched the pants up on reflex. "You cover that hair of yours," she said. "And you put that sweater on. You're too white."

He climbed up onto the deck to retrieve the sweater; she snagged it one-handed off the engine housing as she switched sides, tossed it at him. He worked it on, tugged it down and hitched the pants again before he sat down on the half deck edge to pick up the black scarf where it lay. He wrapped it round with several deft turns and tucked the end. "You can take me to the Hanging Bridge."

"Easy done, but this boat can do the little canals too if you need 'em."

"Hanging Bridge is fine."

She kept the boat moving, push and switch and push. Her feet were warm on the deck. Her breath came hard. Traffic ahead. She kept her side, starboard of a slow-moving pole-barge. She let the boat slow more, city-pace.

"You always work this boat alone?"

Uhnn. Now it comes. Spends a night or so and now the man gets to meddling. So much for love, Jones. Mama said.

"Jones?"

"Sure." She was breathing hard. Sweat rolled down her face and she wished she had a man's option to take the sweater off in the town. She lifted the cap and resettled it on the knot on the back of her head before she thought, set it again and made the next stroke in time. Her feet burned on the deck. Damn showoff. "Do right well for myself." Liar. She sucked a breath and gave him a half-grin and a tilt of the head while she was on the crosspace. "Little different than your hightown sorts, bet they're all soft."

" I'mnot."

She grinned wide. "Hightowner." Gasp. "Be you?"

"What would you have done out there—last night—when the crazies came at you?"

Damn, here he goes. Damn fool question. His damn fault, too, "Hey, man, I wouldn't have been sleeping deaf and blind in the hidey, then, would I? You can bless your

Ancestors I got good ears, that's the truth. Never came so close. I tie up to the Rim, I sleep on the deck, I sleep like a cat, and they don't get up on me like that."

"What if that engine had failed?"

The thought chilled her. She weighed things like that before she did them; she was not prone to mull them over after. "Well, it didn't."

"It might someday."

"Look, usually I go to the Rim in bad seasons; then (here's more canalers and fewer crazies. If my engine goes down I get a tow and it costs me a hell of a lot—did it once." That was a lie. It was what she had done for another canaler, her fuel and theirs together in her struggling engine, and she had taken pay in bits and pieces for a month. "Any more of my business you want to know?"

He kept his mouth shut.

"Takes a damn fool man," she said, "to throw me off my regular ways. Take 'im out where his enemies can't get at him, risk my damn neck, I mean, you want a fool– that'sa fool. How'd I know you wasn't a murderer? How'd I know but what that wasn't some uptown woman's kinfolk throwing you in because you up and jumped her, huh? That'sa fool, being out there alone with you in my boat."

"Why did you do it?"

"Damnfool, that's why. Need a better reason?"

He was quiet a moment. Then: "Jones, what's wrong?"

"Nothing."

"Jones, slow down."

Current hit the bow. She gasped for breath and shifted hard, staggered a bit and lost her balance in the shift of current. Tired. Her sides ached. Her arms were leaden. Sweat ran in her eyes.

"Jones, dammit. Are you trying to kill yourself? We're not in a race."

She ignored him for another barge, maneuvered across the influx from the Snake's harborside loop across the Grand, and avoided the slew the current wanted to give her. It was no place to stop, folk would swear her deaf if she parked at the Jut and had herself in the traffic. Some barge would crack into her and just deserts for a fool. If she was alone she would pull off to the Snake's nearest tie-up and rest. She had shown him a fancy bit of moving; now the damn landsman had that worry-look on his face and that damn insistence in his voice– Fool woman. Quit. Pull off. Let me, lei me, let me—pushing right in to have the boat, his way, tell her what to do, when to breathe and when to spit, and then walk out again with things a damn mess, because he had more important things in life than a damn woman. Walking through the damn world messing folk up and so damn smug-sure it was help. Man with that tone didn't deserve to be listened to. Her mother never would. Spit in their eye, she would. Man catcalled from other barges– Hey, sweet, that boat's too big for you! And worse things. Hey, you want some help? Followed by just what help the bastard thought she needed.

Stay out of my business, she wanted to say. But it was not the kind of parting she wanted; Mondragon wasn't to blame for the world. He just did what others did. Slept with a woman and thought he could get his hands into her life and fix it all before he went back to his hightown ways. Never even thought he'd just seen the fanciest bit of boatmanship he was like to see on the canals. A skip-freighter never got to show off to passengers like the flashy poleboaters; she had just showed him a dozen tricks of the sort canalers showed when they wanted to impress each other, the kind that made a difference in the trade, how a boat could move and handle the tight places. She showed a landsman that kind of thing. And he just saw a woman sweat and got all bothered.

Dammit.

Damned if she'd rest. Take him to the damn bridge and dump him in, she would. Put him back where she found him. Ask for the domes back. That'dfix him good.

She sucked a quieter breath, easier now the strokes were fewer, up past the Jog, under Parley Bridge, and her breath rasped in her throat. She was resting. That was a canaler trick too, getting wind back while she worked. But he was blind to it, same as what it took to shoot the piers and all their currents.

"Jones—" he insisted, looking up at her from the well.

She managed a grin. "You got a problem?"

He evidently thought better of it. She grinned wider. And took it slower still, breathing easier. *'I tell you, man, there's places you don't stop. Park at the Jog back there, some barge'll run right over you. Current takes 'em real close to that wall and they don't see you. Don't care either. Bargemen got no regard for a boat."

That seemed to put some respect into him. He kept his mouth shut, maybe having realized he knew less than he thought.

Fine for you, Mondragon. Got a brain even if they did rattle it. I wouldn't do so good in your hightown. Be a real embarrassment, I would. Leave my boat to me, all right, Mondragon? You don't own everything.

I'll have me a dozen lovers.

Take precautions too, I will.

O God, if he's got me pregnant.

I'd work this boat same's mama did, that's what I'd do; have my kid; wouldn't be alone then. Have a daughter with hair like that—

Lord, I'd have to fight off the bridge-boys with the boathook; have to teach her to use a knife same as mama did me…

Give her to her damn father, that's what. I'd march right up to hightown wherever he's got to and hand him the brat and wish him luck.

Take precautions next time. Going to cost you a week's work, old Mag's drugshop's supposed to be good. Should of had the stuff aboard before now.

Have to walk in that shop in front of God and everybody and ask for that stuff, old Mag'll grin; she'll tell that sister of hers, Lord, it'll be all up and down the river by sunset and I'llbe fending off boarders.

Hey the icewoman's done thawed!

Hey, Jones-pretty. You wanta see what I got?

Damn, nothing's simple.

The bridge-shadows came over them, the air went cold with that deep dankness of Merovingen's depths. The shadows went darker still, a moment of blindness that swept past to daylight. There was a copper taste in her mouth, the loom of a black boat passing beside her—she fended and evaded it, and evaded the gray rough-hewn stone of Mantovan's Jut on starboard. Another skip was ahead, dead-stopped at a mooring ring. "Damnfool." She maneuvered around it, slow drives of aching muscles. 4'Park in the Grand in daylight—" She reached out and rammed the pole end against the boat. " Damnfool, you!"

"Damn bitch!"

"Old man Muggin." She sucked wind as they passed. Looked at Mondragon standing just off the deckrim, gazing back at the boat and its ragged occupant. "Old man thinks he owns the water. He don't handle that boat so good nowadays, long stretches get him, and he won't stay off the Grand." She recovered her breath and poled along with steady strokes again. "You got rules here. You obey 'em, you get along."

"You want to rest, Jones?"

"Hey, I got no need. She's light today. You want to see work, push her when her well's full of cargo, then'swork." She coughed from the bottom of her lungs, missed a stroke. "Just a little—" A second cough seized her, payment for the long push. "Damn." She coughed again, swallowed and got the spasm under control. "Cold. Change always does that to me. Going from sunlight in under the bridges." They passed a poleboat, out fareless. Hunting. It was true, they were well under Merovingen's bridges now, and the water was dark and the walls on either side un-tended and cheerless, their windows and doors barred with iron. No canal-level entry here, except to the lowest sorts of places, that served canalmen. The big isles took their canalside deliveries down guarded bays, within iron gates that guaranteed they got only what they ordered. "What's at Hanging Bridge?"

There was no answer. But it stopped the questions. She worked quietly, wiped the sweat. So much for clean clothes. Hardly dry yet and the sweat soaked them.

"You looking for Them?" she asked him,