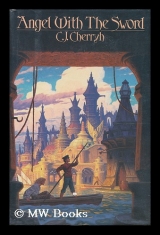

Текст книги "Angel with the Sword"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

The most universal holidays are 24 Harvest, which is the date on which the Scouring began, and 10 Prime, which is the generally accepted date of its ending. The 24th of Harvest is a day of mourning and sober reflection for all religions. The 10th of Prime is a day of celebration, sometimes of licentiousness. The 24th of Harvest is a particularly tense time for police in cities where there is a strong Adventist presence, as the melancholyas Merovans refer to it, may result in overindulgence, which in turn leads to hallucinations or to religiously-inspired and quite cold-blooded decisions on the part of groups or individuals to take direct action against real or imagined enemies. On one famous occasion a band of twenty Adventists from Soghon set out to destroy the sharrh ruins at Kevogi and fought their way through three companies of militia from Soghon and Merovingen who set out to stop them. They cost a hundred and fifty-two lives before the last of them was subdued. The sole survivor of the action was a twenty-two year old man named Tom Caney, wounded in the final assault and later hanged at Merovingen. The incident is generally referred to as the Faisal Rebellion, after its chief instigator.

Other holidays are pertinent to certain religious groups and are celebrated in certain locales but not in others; still others commemorate local events, such as the Festival of the Angel on 20th to 25th Fallow, in Merovingen, which unites a number of religious observances in a mutually agreed date. The general tenor of the festival is a purification and absolution in memory of divine intervention; but sects differ considerably in interpretation. The practice among almost all sects involves the giving of gifts and the mending of broken friendships and lapsed vows before the year's end: there is a belief in Merovingen that this festival is pre-Scouring; and that therefore it is the one festival which intervenes in the period between 24th Harvest and 10th Prime. There is even a legend that in the Det Valley, during the darkest day of the Winter, when sharrh were hunting humans up and down the valley, a band of starving humans decided to celebrate this ancient festival, and in a cave deep in the hills, with the attack going on in the valley, they gave each other gifts that became a miracle– since each of them had secreted things that, brought into the open, helped the whole company survive. The story is perhaps apocryphal; but the festival is observed by all sects and across sect lines throughout the Det Valley in some form; and the practice and the legend have been picked up by the Falkenaer, who devoutly insist that the site of the miracle was the Falkenaer Isles.

The Angel of Merovingen

The Angel, which is a copy of one which did predate the Scouring, was set in its present position in the year 55 After the Scouring, precisely on the 25th Fallow, in a civic ceremony. The original, discovered in about 22 AS in the ruins of Merovingen, disappeared when it was stolen by the governor of Nev Hettek in the intervention during the Adventist riots of 53 AS; the barge transporting it sank in the Det, some believe as a result of Adventist sabotage; some say that the barge was struck by lightning during a storm; and the implication is that the lightning was divinely directed.

Legend states various things about the Angel, which is a gilt figure twice lifesize, of a winged figure in flowing robes either drawing or sheathing a sword. Adventists say that the Angel's name is Retribution, and that he is in the act of drawing. Some say that the sword advances and retreats into the sheath by tiny degrees at each act of humankind that either advances or retards the day of Retribution. Of course this is immeasurable because of the number of people in the world, but some Adventists insist there has been measurable movement.

Revenantists state that the Angel's name is Michael and that he is sheathing the sword which caused the earthquake.

The Church of God agrees in the name and says that he is a divine witness to human affairs, and will remain to guard the world from the sharrh until the Church is restored to its former purity.

The Janes and the New Worlders incorporate him into their own beliefs as an entity of divine wrath which defends humanity from the sharrh: Janes call him the Watcher and New Worlders call him simply the Angel. Replicas of the Angel are venerated in Suttani, the Falken Isles, the Goth, and Kasparl.

The Scouring and Re-establishment

There is an event referred to as the Little Scouring, which was the purposeful demolition of structures and removal of dangerous information offworld by human forces in the face of the sharrh advance and in compliance with the sharrh-human treaty. This demolition was also designed to compel surrender of the holdouts.

It did secure some further compliance. It further and accidentally ensured human survival by driving the colonists into the hills to escape arrest; it also hardened the attitudes of the most determined resistance, the hard core of which was convinced (after repeated betrayal by authorities) that the whole alien threat was concocted by either the companies or the government to take their land.

But on 24th Harvest in the year 2657 of the old reckoning (still used for religious purposes and in official documents) the sharrh came down to eradicate the last remnant of human settlement on Merovin.

The first strike took out the space station, which by then was only a ransacked and stripped hulk. It also hit the major cities with C-fractional strikes, not, fortunately for the ecology and the remaining survivors, with atomics. Subsequent attacks were at close range with beamfire and finally with demolitions and air-to-ground missiles or with rifles as sharrh hunters carried out a site by site search for survivors, and perhaps, though sharrh motives remain obscure, a search for records.

Humans lost ground steadily, and finally devoted most of their energies not to attack but to evasion. This continued through the Long Winter of 2657-58, during which humans suffered from exposure and starvation.

By a time generally accepted as 10th Prime, the sharrh stopped shelling the hills and withdrew their patrols. After that, the sharrh left the world.

It was not until full spring that the first humans ventured out into their former lands. Some of these were true insistence fighters; others were human predators who were as apt to turn on other humans as on the sharrh. And for the next several years, that was the condition of the Det Valley and Megar and Kaspar River.

Eventually places like Kasparl sprang up, freewheeling trading posts founded on ruin; and places like Merovingen, Soghon and Nev Hettek, where farmers and traders reestablished themselves; and the hardy Falkenaer, who stripped their isles of trees in the making of boats of quite different sort than they had used in colonial days; but they had been fisherfolk from the founding of the colony.

This period of rebuilding is called the Re-establishment. It stretched on over fifty years before human life on Merovin achieved any feeling of permanence. These were rough years in which there were numbers of locally notorious bandits and leaders and would-be leaders who rose and fell and left little legacy. Noted in the area around Susain was the bandit Sager, whose band faded away into the elusive desert-dwelling folk who live mostly by trading and by petty theft in the outback around Susain; while in the Det Valley, Nev Hettek took its militia and marched south in 2672, sweeping up local militias by persuasion and threat until they reached the sea and Merovingen, using the Det as a highway for supply and communication which the bandits could not prevent. Generally this military action was hailed with relief, and it gave the Det Valley settlements the earliest start of any in the world in the Re-establishment of human trade and culture. Nev Hettek thereafter made a bid to be capital of the whole valley, but Merovingen refused to bow to its authority, and Merovingian resistance encouraged the militias to remember their regional loyalties, which more than any other factor served to put term to Nev Hettek's dream of being the world capital.

The Earthquake

Among disasters associated with the Scouring was the Great Earthquake. Merovan opinions differ as to whether the sharrh activated the Det Valley fault, or whether the calamity was merely a spectacularly unlucky natural disaster. In any case, quakes were known from the year after the Scouring, but subsided by 2662,

Then in 2690, an earthquake of great magnitude caused severe damage the length of the Det from Nev Hettek to Merovingen, with less disastrous effect for Merovingen, which had been among the most prosperous post-Scouring cities, building on the ruins of the Ancestors. There was a tidal disturbance and flooding in Merovingen, while Nev Hettek suffered extensive damage, but Rogon was completely leveled and abandoned.

The stubborn survivors rebuilt; but nature reserved a particularly cruel turn for the inhabitants of Merovingen. Less troubled by the aftershocks than Nev Hettek and certainly than miserable Soghon, they sent aid north to the relief of Soghon and the survivors of Rogon even in the midst of their own flooding.

But the area remained prey to seismic upheaval for years afterward; and there were floods in Merovingen in the summer of 2691, in 2695, in 2696, in 2698, 2699, and 2700, generally just a flooding of the streets, but in 2696 and 2700 the floods came high enough to cause extensive damage. The early floods were attributed to slight subsidence and unseasonal rams, which had indeed been known during and after the sharrh attacks. It was theorized the fires which attended the quake denuded the land and prevented the retention of water upland. Minor diking and sandbagging took care of the problem in most years.

And there was one curious incident, when floodwaters revealed the Angel of Merovingen, which appeared from forgotten (some said miraculous) provenance, washed to light in the clearing of rubble from the original governor's residence. It was seized upon as a sign of hope by the desperate citizens and contributed to the resolve of Merovingians to stay on the site of their city.

But in 2701 the dikes broke and the floodwaters stayed into winter, shallow enough to wade in most districts, Desperate Merovingians filled basements with nibble, built bridges, and in general survived as best they could.

So Merovingen began to be a city of bridges, but the full extent of the calamity was not evident until 2702, when flooding became worse. Merovingians, prevented by fear of Nev Hettek and by inhospitable conditions to either side of their harbor, stayed put,

Conditions grew worse gradually, men seemed to stabilize by 2710, when Nev Hettek intervened in a flooded Merovingen and proved unable to hold it.

Nature, however, was not through with Merovingen, for in 2720, a quake and a subsequent storm combined to alter the contours of the harbor, which had been undergoing silting and which already had numerous difficulties. Many ships in the harbor were swept from moorings and ground together to their destruction, forming a sandbar that finished the harbor in the years that followed. A new, deeper anchorage was established on the other side of Rimmon Isle. The construction of massive dikes and the eventual lessening of the rate of subsidence helped stabilize both city and harbor.

Legends persist that drowned dead rise from the harbor in the worst storms and crew the ships buried in the shallows of the Dead Harbor, which are occasionally said to rise and sail in particularly bad storms. Further superstitions say that the dead recruit sailors to their midst; that all who die at sea are bound to sunken ships, and that at the final departure of the last human from Merovin, the Ghost Fleet will follow.

The Dead Harbor remains the refuge of the lost and the desperate, the outcasts of every city up and down the Det.

Merovan Names

Generally Merovan names reflect the frequency of names in the area of space from which colonists came: that area itself was a frontier and had, like most frontiers, a fairly polyglot and polyethnic population.

Many original place names honored a discoverer, for example the name Merovin itself: or were the whimsy of mapmakers or colonists; or were historical referents to geographical features of other worlds; and finally, some were sharrh names attached only after the initial terse communique identified certain sites in evidence of sharrh claims.

During the Re-establishment two forces operated within the language: first, a breakdown of formal education and the fact that a few groups were bilingual, using the ground-based equivalent of ship-speech: some small, remote areas were actually dominated by these family-languages, derived from Terran origins. Second, there was a realization in the latter part of the Re-establishment that a great deal had been lost, and there was a conscious attempt to restore original forms both in nomenclature and in speech and to adhere to them.

At the ordinary rate of linguistic change in a society without telecommunications, deepteach, or even minimal literacy in a great deal of the population, six hundred years of life on Merovin might have seen Merovin a patchwork of regional dialects so divergent that average citizens from widely separated regions could not understand each other. But to this tendency of language to change rapidly there was a counterbalance: the profound interest of Merovans in regaining contact with humankind, or in preserving their culture against these changes which Merovans of the Re-establishment saw accelerating in their own time.

The influence of religion on this preservation is extreme but varied: Adventists, believing that humankind will come to rescue them, believe that there is a very substantive reason to preserve the original language, so that they can comprehend instruction from their deliverers, who, they trust, will speak something unchanged: they preserve a recollection of deepteach. Revenantists on the other hand do not believe in an intervention, but believe that preserving the ways of the Ancestors gains merit and that a sort of collective karma or sympathy toward the rest of humanity increases the likelihood of rebirth on another world.

In practice, the priests and the wealthy religious speak an educated, conservative language of forms current six hundred years ago; while there exists even among the upper class educated a vernacular which changes much more rapidly, new words which pepper a more conservative speech and which generally disappear as out of vogue.. There is therefore change, but it is slow. The trades, on the other hand, have evolved a vernacular of their own to handle work and business with implements the Ancestors knew only in principle. And the illiterate (or the functionally illiterate, since some learn their letters for religious motives but cannot read with any skill) have a vernacular which is held to the conservative mainstream only by the necessity to communicate with the upper classes. As oper ative within the illiterate community is the tendency of alienated populations to develop jargon or cant specifically designed to shut out unwanted listeners. In some areas this has become impenetrable dialect; and in others, where Terran languages have compounded the problem, there might be said to exist new evolved languages. An example of this is the Falken Isles, where the original neo-Terran language and the creation of an entire new wooden-ship technology have created a language no outsider can understand.

Likewise a canaler from Merovingen or a fanner from the upper Det can lapse deliberately into an accent so extreme that an outsider might hear few intelligible words; and might misunderstand the contextual meanings of those.

Generally personal names and family names have withstood changes far better than place names. This link with persona] Ancestors is a tie which few Merovans will abandon, particularly in the surname. More flexibility appears in the personal name, which is religiously influenced; but even many sharrists are reluctant to abandon the advantages of an Ancestor-name: some names in particular have social or financial advantage, establishing ties to wealthy families or heroes of the Re-establishment, or establishing ties to privileges which have attached to certain names. In Nev Hettek the Schuler name entails the right to the first booth in the main row of the autumn fair, and in Merovingen the Ebers have the right to direct petition of the governor without going through the Justiciary.

Merovin and Money

In general the world runs on the gold standard, each bank or city able to mint its own coin.

Merovingen and other cities of the Det have a basically standard monetary system, although the coinages differ in imprint.

Examples of such, their colloquial names, and their values in ounces arc as follows; and reckoning gold at $425 and silver at $8 an ounce, a comparison in late 20th century coinage is appended.

Merovingian Coinage

gold coinage sol(dek) 1.60 ounces $680

demi (dem) .70 ounce $297

dece (tenner) .35 ounce $148.75

gram (piece) .035 ounce $14.87

silver coinage lune (silver) 1.60 ounces $12.80

half (half) .70 ounce $ 5.60

dece silver (silverbit) .35 ounce $ 2.80.

gram silver (libby) ,035 ounce $ ,28

bronze coinage

(bronze and copper are reckoned as portions of a silver lune, and fluctuate with the value of the lune.)

penny 1/10 lune $1.28

halfpenny (pennybit) 1/20 lune $ .64

cent 1/100 lune $ .128

copper coinage copper (bit) 1/10 cent $ .0128

Chattalen Coinage

gold coinage credit (cred) 1.60 ounces $680

demis (derni) .80 ounces $340

dekas (dek) . 16 ounces $ 68

silver coinage standard (round) .35 ounces $2.80

silver penny (skimmer) .035 ounces $ .28

copper coinage penny (flor) 1/10 standard $ .28

halfpenny (half) 1/20 standard $ .14

cent 1/100 standards .03

Some idea of the true value of currencies may be gained by knowing the value per ounce of gold and silver on the current market; but where living standards vary widely or where there is a great difference in technological level or a wide gap between rich and poor, a good measure is the cost of a staple such as a day's supply of bread.

In Merovingen 2 cents will buy a loaf of bread or a decent fish; but you would pay 2 or 3 lunes for a pound of imported meat; and while a sweater on a canalside (a better measure than a pair of shoes, since shoes are a luxury there) might sell for a halftone, the very same sweater might go for 8 lunes in an uptown shop; and a silk scarf (imported fabric) could go for a gold dece or 4 lunes silver, Thereis a vast difference between luxury and necessity in Merovingen.

Banking

Each city stamps its own coinage, in gold, silver and base metal. There is also scrip, as traders and bankers exchange letters of credit which are very like banknotes—transferable with appropriate seals and signature—to avoid physical shipment of gold and other valuables from city to city with attendent risks of loss. But a clever thief with a good fence can manage to steal and negotiate letters of credit: corruption does go high up. The common thief, unless well-placed, does not receive near face value: this is the principle deterrent to thievery of such paper. It does notstop those high enough to wash it illegally through cooperative agencies.

Manufacturing and Trade

There are some heavy manufacturing centers on Merovin, Most such industry is located well away from population centers. Some few industries such as the iron and steel mills, the few refineries and the small plastics industry are well organized with permanent employment of skilled staff, but it is considered a hazardous occupation and there are fewer people anxious for employment in what might become prime targets in another Scouring—than might be imagined. Cities generally will not tolerate such centers near them, so they are isolated, which further diminishes the number of job-seekers.

In Merovingen as an example, there are traders, there are cottage industries and small operations like goldsmithing; there are services like taverns; a small iron foundry; there are tiny breweries and distilleries and importers and exporters. There arc those who move freight on the canals. There are the bankers and rich landlords and there are the latecomers and the victims of disasters like flood or political upheaval. And in this economy many transient and many poor live from hand to mouth, in the tradition of their spacefaring ancestors who well understood the benefits of recycling. Anything thrown out is sorted and claimed down the line until very little is actually thrown away.

Merovingen exports fish, salt, and what comes in by sea; artworks, crafts, lace and leatherwork, some drugs and medicines, and many cottage industry items; some weapons; fine metalsmithing; fertilizer.

It imports: petroleum products, some drugs, textiles, grains, meats, leathers, raw metals.

In various adjustments for local abundance (Nev Hettek, for instance, is in the grain belt for the whole Det Valley and has grazing animals, but imports some fish and produces some little amount of petroleum) this is representative of Det Valley trade; and quite representative as a unit of other areas.

The tropics produce other items which arrive at Merovingen, among them raw materials and exotic luxuries and exchange is for the petroleum the Chattalen totally lacks.

Clothing and Fashion

Since the technology of Merovin was mid-27th century gone backward, Merovan technology is a hodgepodge of the modern and the makeshift. Merovin has forgotten a great deal that it once knew; certain areas of the globe remember things that other areas have forgotten due to the presence of a particular group of individuals who retained the knowledge, due to the preservation of records, or due to the prevalence of an industry elsewhere in disuse—an example of the latter being the petroleum industry in a few areas around the globe.

It is an advanced technology reduced to an earlier technology and hindered by an artificial cap, ie, that advanced technology is frowned upon.

The tendency in furnishings and dress and even in manufacture is toward the baroque: ornament for ornament's sake, but founded on a Classic age (the 27th century) which was austerely simple and high-tech. So in many respects this tendency to the baroque wars with the Classic ideal, and the result is a combination of 27th century pragmatic simplicity—for example the idea that clothes and furniture should be comfortable above all else; and the tendency of Merovan craftsfolk to embellish and complicate what they produce. Fashion exists in a few larger cities, and particularly in the Det River cities, where the river affords more than usual movement of ordinary citizens (as opposed to traders) from one city to the other, and where there exists considerable social division. In the Det Valley and also (but differently) in the tropic Chattalen, exists a concept of modishness, with all the attendant expenditure on changing fashion.

There is, underlying all of this concept, that persistent Classic ideal, which looks back to the sleek, simple comfort of 27th century dress which relied on advanced materials, and which had no particular gender-distinction. So whatever local dress has become, it is worldwide from the same origin. Since the prosperity of the Colonial period established itself in the popular mind as the epitome of human development, the tendency was to preserve the basic garments and to add accoutrements and ornament.

In Merovingen-below, certain economic factors bear on style of dress. There are terrestrial cattle on Merovin, imported along with humans, but the term also includes native animals down to some the size and habits (but not the taste) of swine. There is no refrigeration except such amenities as rootcellars and springhouses, ice in the southlands being a very rare commodity. Most meat is smoked, dried, or preserved in brine or by canning. A city like Merovingen, with abundant fish, imports little meat, except for the palates of the rich; a few small towns to the north supply Merovingen with the little amount of fresh meat it gets. The fact that both Nev Hettek and Soghon are cattle-raising areas which supply most of their own needs combined with the problems in refrigeration and Mero vingen's own reliance on local beef, tend paradoxically to discourage the development of any major cattle industry in the north of Megon. Ifrefrigeration were common it would be a different matter. As it is, the only animal product which does come downriver from that industry in any great abundance is leather; but again, scarcity, relatively high price, and the very mundane realities of a city on canals dictate that the majority of Merovingians who live on the canalsides go in wooden clogs for work, even though they will keep a pair of leather shoes for going off thepremises or otherwise go barefoot more acceptably than wearing clogs onto the noisy bridges and balconies of Merovingen-above. Canalers on the other hand go barefoot in all but the coldest weather, simply because footgear is more often soaked than not: the worst weather usually sees an amazing variety of footgear, which varies from leather boots to (more commonly) ropesoled canvas. The only leather item a canaler will generally possess is a belt. Middletowners wear practical, heavy leather articles which are expected to last for years; and only the very rich remain to keep the cobblers well-to-do. But the rich as a class are not enough against other difficulties, to encourage a vast meat and leather industry to the north—all of which serves as a very small example of the intricacies of economics, trade, and Merovingian style.

A great deal of knowledge of textiles survived the Scouring. There is no industry supporting synthetics and in the abundance of local natural fibers and materials, and the universal fear of technology, there is no driving impetus to create a large plastics industry. In the Det Valley, as an example, there is some wool industry, the majority of which is used in the colder north; there is abundant cultivation of a local flax-like plant which produces a very serviceable linen or cotton-like material; and on one occasion angry Revenantist farmers burned a barge of a Nev Hettek refinery which experimented with sheet plastics, which they saw as a threat to their livelihood and a Provocation against the sharrh.

Weaving is a very advanced art, using some power looms; jacquards and corduroys are not out of reach. There is a very tough sailcloth-derived weave called chambrys. Chambrys is dyed a variety of colors (mostly indigo and brown and black) and is universal among working classes: of a fiber tougher and more resilient than cotton, it resists abrasion and takes amazing abuse. The same linen fiber is also widely used, though differently prepared, for knitting. There is silk, imported from the Chattalen, of high quality. There is felt and fur; and there is (another import) an airy vegetable-derived fiber very like fine combed cotton which is rarely seen in the lands of the Sundance. Waterproofing is accomplished generally by oil and wax, though the Wold is beginning a rubber industry which has met several setbacks similar in nature to the incident of the Det Valley farmers.

The mode of dress almost universal in the Det Valley is a pair of durable trousers and a sweater, be it Merovingian canal-rat or hightowner from the uppermost ranks of society, or a citizen of industrial Nev Hettek. But while the northern lands favor knee-high boots in all seasons, the Merovingian poleboatman will go shod as a rule, and have his trousers no longer than mid-calf; and wear black or brown stockings which show no effects of an occasional wetting or of dirt. The skip-boatman will go barefoot; the canalsider will dress much the same except for stockings and clogs or occasionally leather shoes; while the uptown resident will maintain a certain flair of fashion, fine knee boots, a scarf, a sweater designed to expose an embroidered high collar, or one flared silk sleeve, always with a certain coordination of color, usually dark, which distinguishes one of the gentry going casual: and not uncommonly accompanied with a very utilitarian sword-belt or belt-knife. A scarf for the head, tied bandanna-fashion, is not improper in Merovingen, where seasonal fogs wreak havoc with careful coiffure; and not uncommonly this is crowned with a hat, usually of sweeping brim which serves a practical purpose in inclement weather. Hats are a practical development in which a great deal of local character manifests itself; a few are of traditional form, like the canaler's cap; but vanity runs rampant among the gentry.

There is one gender distinction which was present in the

Classic period and which still remains, in the Det Valley and in most other places: women of the upper classes particularly, but generally of all classes, use cosmetics. There are communities particularly among those dominated by certain Revenantist sects, where this is not the case. Cosmetics among both men and women are common in the Chattalen. Jewelry ranges from elaborate (the Chattalen and the Suttani region) to the stylishly restrained (Mero-vingen). In Merovingen, ringer rings are virtually universal, a solitary earring is not uncommon in either gender, and necklaces for formal occasions are a throat-encircling collar sometimes worn over a shirt's self-collar (either gender) but among the truly elite the jewelry is actually stitched to the collar—so that one is obliged to have quite a lot of jewelry to maintain a wardrobe. Many an aspirant to the upper society may tax his or her servant in the constant transfer and re-arrangement of jewelry to a variety of shirts.

The ordinary dress of the Merovingian hightowner is boots and close-fitting trousers, usually dark but not always; and a shirt of white (or in some years, almost any color) linen or silk usually hiplength and belted, having flaring sleeves embroidered about the cuffs and about the high, throat-circling collar with floral patterns; in modification this is also the pattern of the workman's shirt, which is of more durable fabric.