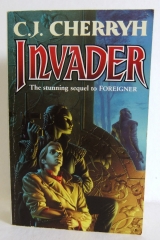

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

" Are they– easy to get along with? Can you talk to regular atevi? Or are you pretty well guarded?"

"I deal mostly with government people, but not exclusively. Atevi are honest, loyal to their associates, occasionally obscure, and occasionally blunt to the point of embarrassment. I'll be delighted to have another human face besides the one in the mirror, but I don't live a deprived life here. Let me ask a more technical question. What are your landing requirements? What do you need? A runway?"

" Actually– not, sir. I wish we did. We're using one of your pods."

"You're kidding."

"Afraid not. They found a couple in the station, packed up and everything."

"Good God. – Excuse me."

" So we've got no way back up again if somebody doesn't build a return vehicle. Between you and me, sir, in language you wouldn't tell my mother, who's not real happy with this– what risk am I running?"

"I'd sure want to know why those pods didn't get used."

"Mospheira says they were redundancies. There were three last ones. Because the last aboard the station were only six people. And if anything had gone wrong with one, they couldn't have built another. They had a rule about triple redundancy."

"That sounds reasonable. But I can't swear to it."

" So– if we have to build a ship that can get off the planet, how long is it going to take to get us back up again?"

"If we started today, if things went incredibly right, and that was our total objective in the program, we could maybe launch a manned capsule to low orbit inside a year, year and a half, on a rocket that's meant to launch communications satellites. No luxury accommodation, but we could get you up to low orbit and probably down again in one piece."

"But to reach high orbit?"

"Realistically, and I know this part of it, because I'm the technical translator, among my other jobs, if we want a meaningful high-orbit vehicle, we'd be wasting time building a small-scale chemical rocket. I'd much rather negotiate an orbit-and-return technology."

"And how long for that?"

"Depends on a lot of factors. Whether the materials meet design specs. How much cooperation you can get from the atevi. I'd say if you don't want to grow old down here, you'd better land on this side of the water and be damn nice to Tabini-aiji, who can single-handedly determine how fast the materials are going to meet design standard."

" That's– very persuasive, sir."

The whole business of haste – the rush to risk lives – bothered him. "A parachute two hundred years old? The glue on the heat shield —"

"We know. We propose to refit it. They say they can improve on it. Put us down pretty well on the mark. I don't personally like this parachute idea, but I guess it beats infalling without one."

"You've got more nerve than I'd have, Mr. Graham. I'll give you that. But our ancestors made it, or we wouldn't be here."

" I hate to ask, but what was the failure rate? Do you have any stats on that?"

"Percentage? Low. I know that one sank in the sea. One hard-landed. Fatally. One lost the heat shield and burned up. They mostly made it, that's all I know. But with all your technology – isn't there some way to take a little time, at least modify that thing into a guided system? Nothing you've got can possibly serve as a landing craft?"

A pause. Then: " Not for atmosphere. The moon– no problem. But that's a deep, deep well, sir."

"Gravity well."

"Yes, sir."

It wasn't just Mospheira versus atevi that had a language gap. He guessed the shortened expression. And out of the expertise the technological translator necessarily gained in his career, other, more critical problems immediately dawned on him.

"Mr. Graham, I hope to hell if they unpack that parachute to check it, they know how to put it back in its housing. There's an exact and certain way those things have to unfold. Otherwise they don't open."

"You're really making me very nervous, sir. But they've got specifications on the lander. That's in the station library, they tell me."

"When are they sending you down here?"

"About five, six days."

"God."

" I wish you'd be more confident."

"Five days is pushing real hard, Mr. Graham. Is there a particular reason to be in a hurry?"

"No reason not to– I mean, we've no problem with ablation surfaces. We can do better in no time. I'm less sure about the parachute, but I have to trust they can tell from records. That's all. I have to trust it. And they'll be done, they tell me, in four days. And they can shoot us out there on a real precise in/all, right down the path. I don't know what more they can do. They say it's no risk. That they've got all the results. When did they lose the three they lost? Early on?"

"I think – early on. They didn't lose any of the last ones." A slight gloss of the truth. But the truth didn't help a man about to fall that far.

" I'll tell you, I'm not looking forward to the experience. I keep telling myself I'm stark raving crazy. I don't know what Yolanda's thinking. But if we just get down—"

"The atevi would say, Trust the numbers. Get fortunate numbers out of the technicians."

" I certainly intend to. – What's that sound?"

"Sound – ?" He was suddenly aware of the outside, of the smell and feel of rain in the air. And anxiety in Graham's voice. "That was thunder. We're having a storm."

"Atmospheric disturbance."

"Rain."

"It must be loud."

"Thunder is. Can be. That was. It's right over us."

"It's not dangerous."

"Lightning is. Not a good idea to be on the phone much longer. But one thing I should mention before I sign off. We've never had much of a disease problem, there's not much we catch from atevi, and we were a pretty clean population when we landed. But on general principles the aiji will insist you undergo the process our ancestors did before they came down."

"We began it last watch. My stomach isn't happy, but that's the least of our worries."

"Sorry about that. I'll relay your assurance to the aiji and I assure you the aiji will be happy you've taken that precaution on your own initiative. You'll impress him as considerate, well-disposed people. I'll also inform him about your companion needing to get to a plane without delay, assuming that will be her wish. I'll fax up a map with the optimum sites marked, with text involving advantages and disadvantages. You can talk to your experts and make a choice, but it's just more convenient to the airports if you can come in on the public lands south of the capital."

"I'll pass that word along. I'd like to talk to you fairly frequently, if you can arrange it. I want to look over this material you're sending up. I'll probably have questions. "

"I'll fax up my meeting schedule. Tomorrow I'm going to be traveling out to an observatory in the mountains. I'll be back by evening. But if something comes up that needs information from me, wherever there are telephones, they can track me down. Even on the plane."

"To an observatory. Why?"

"To talk to a gentleman who may be able to answer some philosophical questions. Your arrival has – well, been pretty visible to anyone in the rural areas. And call it religious implications, as well as political ones. Say that concerned people have asked me questions."

"Is that part of the job?"

"I hope we'll be working together."

" I assure youI hope we II be working together, sir. I'd just as soon they dropped us someplace soft."

He couldn't help but grin, to a featureless phone. "I'll pick you out a soft one, Mr. Graham. My name is Bren. Call me that, please. I've never been 'sir.'"

"I'm Jase. Always been. I really look forward to this. After I'm down there."

"Jase. I'm going to be very depressed if you don't make it. Please have those techs double-check everything. Tell them the world will wait if they're not sure. The aiji will. Under no circumstance would he want you to compromise your safety."

"I'm glad to know that. But I guess we're on that schedule unless they find something. To tell the truth, I'd just as soon be done with that part of it."

"We're on the end of our time." Thunder crashed, shocked the nerves. "That was a loud one. I should sign off now."

"Understood. Talk to you later. Soon as I can, anyway. Thanks."

The tea had cooled. The wind from the open doors was fresh and damp. Toby'd been right, the storm had swept right on past Mospheira and on to them in all its strength. The plane with the requested tomato sauce probably still hadn't made it in, and the paidhi had let his tea cool in that wind, talking on the phone with a man born in space at a star other than the sun.

A star the man still hadn't named for reasons that might not be chance.

Jason Graham claimed twenty-eight as old Earth measured years. The faxed-down information that preceded the call gave his personal record – his and his companion's, Yolanda Mercheson, thirty-one and an engineer trainee. Nice, ordinary-looking woman with what might be freckles: the fax wasn't perfect. Jase had a thin, earnest face, close-clipped dark hair – which was going to have to grow: ateyi would be appalled, and understand, because, different from centuries ago, they understood that foreigners didn't always do things for atevi reasons.

But two people of a disposition to fall miles down onto a planet and be separated from each other by politics, species, and boundaries for reasons common sense said surely weren't all altruism, or naive curiosity – he didn't understand such a mentality; or he thanked God it wasn't part of hisjob. He supposed if they talked very long, very hard —

He still didn't know, and he believed Jason Graham saying he was scared. The ship had come up with its volunteers very quickly. Which might be the habit of looking down on places, and the nerve it took to travel on such a ship – he had no remote knowledge what their lives were like on the ship. It was all theoretical, all primer-school study, all imagination. Atevi occasionally had a very reckless curiosity. But he didn't think that curiosity was all that motivated Jase Graham and his associate: humanly speaking, he couldn't see it, and he couldn't find it in himself to believe someone sounding so disarmingly – friendly. For no reason. No —

– reason such as he had to trust the tea he was drinking. Because the woman who served it had man'chito Damiri… he was relatively sure; and Damiri had, toward Tabini, whatever atevi felt for a lover… he was relatively sure. Above all else…

He supposed the ship folk had their own set of relatively-sures, and were prepared to risk his on his say-so. That that was the case… he was less sure; but it was the best bet, the only bet that led to a tolerable future.

It was just daybreak, and he was sitting in the absent lady's office. He shot his dataload up to the ship. Another war of dictionaries.

Of grammar texts and protocols.

He started, then, to phone down to Hanks, and stopped himself in time, remembering the hour was still godawful, and Hanks would justifiably kill him.

Doubtless Ilisidi was at breakfast, on her balcony below his. She might accept a visitor at this hour. He almost wished he were there. But Ilisidi's was a company too chancy for a man grown suddenly human and vulnerable this morning. He wished for bright sunlight, for the atevi world to take shape around him and make his existence rational again. He couldn't afford the impulses that were running through him now, things like instinctual trust, irrational belief in someone on a set of signals that touched something at a level he no longer trusted existed. Not really. It was safe to believe in some other business.

But not in international politics. Not when there were people, human and atevi, who were very, very good at being credible, whose whole stock-in-trade was sounding so straightforward you couldn't doubt. He wished to hell Jase Graham had affected him otherwise. But the man scared hell out of him – scared him forJase Graham, if he could believe the man, and scared him how ready he was to jump to those instincts, inside. If it was real, he hadn't time to give to another set of human relationships than the ones he had, flawed as they were, and it wasn't fair of fate to hand him a human being he could learn to like, that could waken instincts he couldn't otherwise trust, that could divert his attention from a very vital job —

Ironically – it was something like atevi described, that damned flocking instinct, that biological something that intervened in the machimi plays, and diverted some poor damned fool from the man'chihe'd thought he had to the man 'chihe really had, and the poor damned fool in question stood center stage and agonized over the shattering of his mistaken life and mistaken relationships – before he went on to wreak havoc on everything and everyone that remotely seemed to matter to him.

A human watched the plays, trying to puzzle out that moment of impact. A human studied all the clues and knew there was something there.

A human might have finally found it on his own doorstep, in this unformed dawn, this gray, slow-arriving day, shot through with lightning flashes.

One could see the Bergid, now. One could see the earliest lights in the misting rain.

He hadn't premeditated the invitation to informality, but he'd felt comfortable with Jase Graham, even —

Even knowing now that dawn and sanity were arriving, that he had a daunting task in the man – someone who might – what? Trail years behind him in fluency, have a different cultural bias, a constant matter of explaining, defining, reexplaining, a lifetime of study crammed into – what, a handful of years, after which the ship left and another human link went away, left, went dead.

They might not even get here if the pod failed. The thought upset his stomach, unsettled him at some basic level he wasn't accessing with understanding. It was beyond self-pity this morning, it was all the way to stark terror: he was feeling lonely and cut off from humanity, and that – say it – friendly– voice had shaken his preconceptions, gotten through his defenses. He ought to know better. You wanted something and it never, ever quite —

Matched up to expectations? Hell, he wasn't the first human in the world to marry a job, break off a human relationship. He talked to a human being he marginally responded to and all of a sudden his brain was scrambled and he was facing that parachute drop along with Jase Graham as if he had his own life riding on that chute opening.

All those forbidden things he'd disciplined himself to write off, except Barb, who'd turned out as temporary as he'd planned at the start of their association, and he couldn't fault that in Barb. He was the one who'd gotten too close, broken the rules, come to the end of what he shouldn't have relied on lasting in the first place.

And he was damned close to another dangerous precipice, an expectation of some outcome for what he did. Write that off double-fast: it didn't happen, any more than for the paidhiin before him, that he'd ever look back at the accomplishments of a lifetime and say, We won; let alone, It's all solved. It wasn't that kind of a job: it didn't just happen in one paidhi's lifetime. Atevi in space, humans returned to the station, the whole bispecies world enabled to break down the cultural and psychological barriers and live and work together in some Utopian paradise of understanding —

That was the God complex they warned you about when you embarked on the program and reminded you of it anytime you grew extravagant in your proposals to the committee. They showed you the pictures of the dead and the wounded in the war and they told you that was where too much progress too fast led you, right down the fabled primrose path to the kind of damage atevi and humans could do each other now that atevi and humans had much more advanced weapons – not only because certain ideas could be dangerous, but because change had to reverberate slowly through atevi society, and that it wasn't wise to add another set of vibrations before the first set had dissipated down to harmlessness, or one risked an untoward combination of effects that humans just weren't able to foresee.

Damned sure it wasn't the moment to lose his head and start expecting things were going to work. It was his job constantly to anticipate the worst, and to expect the parachute wasn't going to open. Most of all, baji-naji, the demon in the design: never expect common sense on both sides of the strait at the same time.

He walked out of the office and toward the breakfast room, as servants, some doubtless nursing hangovers, paid rapid bows and hurried off to that communications network they had that assured him if he sat down at the table his breakfast would turn up very soon.

He opened the glass doors onto the balcony and enjoyed the cool, damp wind. He had to brief Tabini, he ought to brief Hanks, he ought to brief Mospheira if he could get a call through to the Foreign Office.

God knew – he really ought to call the presidential staff and explain to George. Take a couple of antacids and see if he could work up the stomach to talk directly to the head of staff on the phone – assuming that Mospheira let the phones work this morning, and that the FO could get him patched through.

But he had a Policy Committee meeting before noon. He had a meeting with Tabini to set up. He had an interview upcoming with network news – a request had been waiting for him with the morning tea, and he'd confirmed it: the news service had found out, one assumed, that the paidhiin were holding conferences, that there were answers, that there was, in fact, another Landing imminent. He had a flight out to the Bergid and back staring him in the face.

He ate breakfast while he ran a voice-to-written copy of the tape, one of the mind-saving as well as finger-saving pieces of software he'd cajoled the censors into allowing across the strait. The program wasn't worth using for dictation; he was far more fluent without thinking about it and the damn thing mistook phonemes with no consistency or logic whatsoever, that he could discover: it took more head work to figure out what word in Mosphei' the thing had distorted than it did to do it in the first place, but on a transcript of a considerable amount of recorded speech it was a help.

Especially if it let the paidhi have breakfast while it ran. And a little fuss with spell-check and a visual once over let him fix the truly inane conversions that had gotten past the software and send it through the second phase translation, that at least gave him a framework to render into atevi script.

Half an hour's work and he had two sets of copies: of the tape itself, for the Foreign Office, for his records, and for Hanks – With my compliments,' he sent to Deana, expecting a retaliatory note. And, while he had a line to Mospheira, with his mother's number: Drop me a line on the system. I'm worried about you.

Of the translation – a copy first to Tabini, with: Aiji-ma, I find the tone and purpose encouraging. I have undertaken to meet their descent and to find a suitable landing site such as serves for the petal sails. I wonder is the plain below Taiben suitable and reasonable, being public land? To the hasdrawad: nadiin, I present you the transcript of my first conversation with the chosen paidhi from the ship. I find him a personable and reasonable man. And to Ilisidi, with: One has reason to hope, nand' dowager.

To his own security, then, via the house security office: I am encouraged by the tone and content of my initial conversation I have had with this individual. I hope that he and his companion make a safe descent. I look forward to dealing with this gentleman.

"This seems a judgment of feeling," Tabini observed, when they had a chance, over lunch, to talk in Tabini's apartment. "Not of fact. There is no actual undertaking on their part to perform in any significant regard – and they're dealing with Mospheira. One would think they mean to bargain down to the last moment."

Right to the soft spot. Count on Tabini.

"I've tried very analytically to abstract emotion from my judgment," Bren said. "I agree that there's a hazard in my interpretation: I'm apprehensive of my own instinctive reactions to the man I talked to, aiji-ma, and I'm trying to be extraordinarily cautious at each step. I do judge that these are brave people, which makes them valuable to their captain, there's that about them: among humans, their willingness to take risk means either the risk is small, they're sensation-seeking fools – neither of which I think is the case – or they're people with an extraordinary sense of duty above self-interest."

"This man 'chi-like'duty.' To whom?"

"That's always the question, aiji-ma. They're very plain-spoken, very forthcoming with their worries about the descent, their worries about being stranded down here. They asked straightforward questions… well, you'll see when you read the transcript. We discussed landing sites. I did warn them very plainly they should land here rather than Mospheira, and that it was a matter of protocol. I hope I was convincing."

"This choice of Taiben," Tabini said. It was a private lunch, only Eidi to serve them, while Tano waited outside with Tabini's other security. The violence of the morning storms had passed and the daylight was, however gray, far stronger beyond the white gauze of the curtains. "Taiben – is an interesting idea. Among other sites with other advantages. Let's see what the ship people think important. Speed of transport – Taiben certainly has. And with public lands, there's no clearance to obtain."

"The south range is flat," Bren said. "And unwooded. It's a very dangerous thing they're attempting. I've serious doubts they understand this technology very well. There's a knack to stone axes, so I'm told, that makes it no sure thing for moderns to do."

"Why, do you think, they've no better choice?" Tabini asked. "Are these not the lords of technology? The explorers of the bounds of the universe?"

"I find it – though it's only a guess, aiji-ma – very logical that they have no means to go down into an atmosphere. Our ancestors left their home planet to build a station in space, not to land on a world. They certainly had no craft adequate when our ancestors wanted to come down here. The station folk refused to build one then: if they had, all of history would be different. And if the Pilots' Guild had been willing to fly the craft, those who did land might have built better. The landing capsules, the petal sails, were the only alternative my ancestors had, then – and it's ironic that they're all that exist now."

"All this vast knowledge," Tabini said, "and they fling themselves into the world like wi'itkitiin off the cliffs."

"Without even the ability to glide." A thought came to him. "I halfway suspect they don't know how to fly in air. It surely takes different skills. They wouldn't be trained for it. Flaps and rudder. They don't work in space."

"Meaning these lords of the universe can't land? They only exist in space, where you say is no air, no breath at all? They've forgotten how to fly?"

"In storms like this? There aren't any in space, aiji-ma. Other things, other dangers, I'm sure – but weather and air currents have to be very different for them."

"Which means all the pilots that cannavigate the air – are Mospheiran humans and atevi."

"Meaning that, yes, I would suspect so."

One saw the estimation of advantage dawning in Tabini's eyes. Thought, and plan.

"There is, then," Tabini said, "– if one builds this go-and-return craft you talk about – a point at which it is actually an airplane, dependent on air and winds."

"Yes, aiji-ma."

"I likethis notion, nand' paidhi."

Nobody put anything over on Tabini. And one had to count on Tabini understanding exactly where his advantage was.

They talked also about the office expenses. Tano had sent a proposed budget, and Tabini passed it off with, "Household expense. Doesn't the Treaty say we would bear such expenses?"

Household expenses. A member of the tashrid had that kind of staff. A lord of a province. The paidhi was embarrassed – literally – and said, "Thank you, aiji-ma," very quietly, mentioning no more of it.

Tano, meeting him at the door, simply said, "One thought so. The elderly retired gentleman will be very pleased. He's of my clan."

"Ah," Bren said. On Mospheira one called it nepotism. On the mainland, one was simply relieved one understood where man 'chilay, definitively and absolutely. Noelderly retired gentleman would disgrace even a junior member of the Guild. "What is he retired from, actually, Tano-ji?"

"He was Senior Director of External Communications for the Commission on Public Lands, and very skilled at politics," Tano said. "The commission has very many serious disputes and inquiries."

"That seems appropriate," he said. "I'm very grateful, Tano. I'll meet with the people as soon as they've set up the office. Please tell them so. Does one send flowers?"

"It's not strictly required, but a felicitous arrangement and good wishes from the paidhi, also ribbons, if there were time —"

"Can we do it now? Before the press conference?"

"One could. I could find the ribbons. I could work the seal, nadi Bren."

One-handed sealing was a problem. But atevi set great store by cards, ribboned with the colors of office or rank, and stamped with official seals, as keepsakes, mementos of service or meeting.

"We should have them for all the staff, too," he decided. "Those that have served as well as those that will."

"That's a good thought," Tano said.

"I wouldn't offend the security staff if I gave them ribbons?"

Tano looked actually shy, at the moment. "One would treasure such a gift, nand' paidhi."

"You saved my life, Tano-ji. If ribbons would please you – by all means. Or anything else I can do."

"Nand' paidhi," Tano said, and caught-step and bowed as they walked the hall. "If yougive a ribbon, my father will believe I've achieved distinction. Give me one for me to give to him, paidhi-ji, and I'll hear no more of being an engineer."

Such gestures counted. He'd never thought of doing it for the staff, and wished he had. He had a list, by now, of people he should send cards to. Everyone on staff at Malguri. Certainly every man and woman who'd risked his life for the paidhi's.

That had grown, he realized with some dismay, to a very long list.

CHAPTER 14

The reporters had notepads full of questions: having found a chance to have the paidhi-aiji alone to themselves in a room, they'd naturally come armed with very specific and sometimes unanswerable questions, such as, Where does the ship come from, nand' paidhi? And: What does the ship want, nand' paidhi?

The first of which he couldn't answer, and didn't dare try to surmise: he didn't want to touch the topic of stars and suns; he segued desperately to the second question, which he could answer honestly enough on a level anyone not on the ship could possibly know: "Nadiin, by all it's said so far, the ship folk want the station restored to operation. They expected to find things the way they left them. And of course nothing's the same, not even the station they expected to be waiting for them. They're puzzled, and they're trying to find out what's happened to the world since they left."

He didn't mention the ship's desire to get a fair number of workers from the planet up to orbit, and left that to the reporters to ask if they thought of it. But one reporter asked how he viewed the Association's economic outlook, and what the impact was on relations with Mospheira.

To which he answered, "Nadiin, the Treaty was never more important to us or to Mospheira than it is now. Experience shows us how we can moderate the effects of change: history tells us that atevi will, in the long run, profit from this event, and the ones willing to research their investments thoroughly – I stress 'thoroughly' – should fare very well in industry. Space science is not a new proposition in Shejidan. Many companies already have important positions in space-age manufacturing, communications, and commerce."

"I also have a message for all the thousands of children who've written to the paidhi, asking if the machines will come down again or if the station will come down and shoot at people. And the answer is, No, the machines won't come down. No one will shoot at anyone. Tabini-aiji and the ship captain and the President of Mospheira are all talking by radio about how to fix the space station so that people can live there again – as I hope some of you may live there when you're grown. I've talked to a man on the ship who'll come down very soon to live in the Bu-javid, and be paidhi for the ship and the atevi. He's a young man, he's quite pleasant and polite, and he wishes to help atevi and humans to build a ship that will fly back and forth between the station, something like an ordinary airplane. You may see this ship-paidhi soon on television. He's been a teacher, just like your teachers in school, and he's coming to learn about atevi so he can tell his people about you."

"Ask your parents and your teachers about living in space, and what you'd do if you lived there and looked at the world every day from much higher up than an airplane flies. I may not be able to answer each and every letter you send to me, but I do thank you for writing and asking, nadiin-sai, thank you very much for your good questions."

He drew a deep breath. And thought – God help us. Where do you start with the kids? What are they seeing but invasions and battles on television?

He said to the reporters, "Nadiin, please urge your station managers to think carefully what the children see on television, at least until the news is better. The paidhi asks this, on his own advice, no other."

"Bren-paidhi, what isthis news about another paidhi?"

"Two, actually, a man who'll come to Shejidan and a woman who'll go to Mospheira, each invited, each anxious and willing to assure a good relationship with the planet. Our talk was, as I've said to the children, pleasant, informative, and dwelt on the good of both humans and atevi. They've no other way at the moment to descend to the planet but to use the petal-sails our ancestors used. Only two such craft remain, and they'll use one for the two of them to come down – as early as five days from now. It's very dangerous, to my thinking, but perhaps ship folk believe they can moderate the dangers."