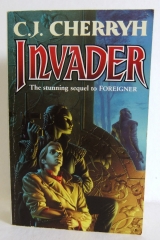

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

INVADER

Caroline J. Cherryh

the second foreigner series novel

CHAPTER 1

The plane had entered the steep bank and descent that heralded a landing at Shejidan. Bren Cameron knew that approach for the north runway in his sleep and with his eyes shut.

Which had been the case. The painkillers had kicked in with a vengeance. He'd been watching the clouds over Mospheira Strait, the last he knew, and the attendants must have rescued his drink, because the glass was gone from the napkin-covered tray.

One arm in a sling and multiple contusions. Surgery.

This morning – he was sure it had been this morning, if he retained any real grasp of time – he'd waked with a Foreign Office staffer, not his mother, not Barb, leaning over his bed and telling him . . .God, he'd lost half of it, something about an urgent meeting, the aiji demanding his immediate presence, a governmental set-to that didn't wait for him to convalesce from the last one, that he thought he'd settled at least enough to wait a few days. Tabini had given him leave, told him go – consult his own doctors.

But the crisis over their heads wouldn't wait, evidently :he'd had no precise details from the staffer regarding the situation on the mainland – not in itself surprising, since the human government on Mospheira and the aiji's association centered at Shejidan didn't talk to each other with that level of frankness regarding internal affairs.

The two governments didn't, as a matter of fact, talk at all without him to translate and mediate. He wasn't sure just how Shejidan had made the request for his presence without him to translate it, but whoever had made the call had evidently made Mospheira believe it was a life-and-death urgency.

"Mr. Cameron, let me put the tray up."

"Thanks." The sling was a first for him. He skied, aggressively, when he got the chance; in his twenty-seven years he'd spent two sessions on crutches. But an arm out of commission was a new experience, and a real inconvenience, he'd already discovered, to anything clerical he needed to do.

The tray went up and locked. The attendant helped him with the seat back, extracted the ends of the safety belt from his seat – and would have snapped it for him: being casted from his collarbone to his knuckles and taped about the chest didn't make bending or reaching easier. But at least the cast had left his fingers free, just enough to hold on to things. He managed to take the belt in his own fingers, pull the belt sideways and forward and fasten the buckle himself, before he let it snap back against his chest, small triumph in a day of drugged, dim-witted frustrations.

He wished he hadn't taken the painkiller. He'd had no idea it was as strong as it was. They'd said, if you need it, and he'd thought, after the scramble to get his affairs in the office in order and then to get to the airport, that he'd needed it to take the edge off the pain.

And woke up an hour later in descent over the capital.

He hoped Shejidan had gotten its signals straight, and that somebody besides the airport officials knew what time he was coming in. Flights between Mospheira and the mainland, several a day, only carried freight on their regular schedule. This small, forward, windowed compartment, which most times served for fragile medical freight, acquired, on any flight he was aboard, two part-time flight attendants, two seats, a wine list and a microwave. It constituted the only passenger service between Mospheira and the mainland for the only passenger who regularly made trips between Mospheira and the mainland: himself, Bren Cameron, the paidhi-aiji.

The very closely guarded paidhi-aiji, not only the official translator, but the arbiter of technological research and development; and the mediator, regularly, between the atevi capital at Shejidan and the island enclave of human colonists on Mospheira.

Wheels down.

The clouds that had made a smooth gray carpet outside the window became a total, blind environment as the plane glided into the cloud deck.

Water spattered the window. The plane bounced in mild buffeting.

Unexpectedly rotten weather. Lightning whitened the wing. The attendants had mentioned rain moving in at Shejidan. But they hadn't said thunderstorm. He hoped the aiji had a car waiting for him. He hoped there wouldn't be a hike of any distance.

Rain streaked the windows, a heavy gray moil of cloud cutting off all view. He'd arrived in Malguri, far across the continent, on a day like this – what? a week or so ago. It seemed an incredibly long time. The whole world had changed in that week.

Changed in the whole balance of atevi power and threat – by the appearance of a single human ship that was now orbiting the planet. Atevi might reasonably suspect that this human ship came welcome. Atevi might easily have that misapprehension – after a hundred and seventy-eight years of silence from the heavens.

It had also been a hundred seventy-eight years of stranded, ground-bound humans on Mospheira making their own decisions and arranging their own accommodations with the earth of the atevi. Humans had been well satisfied – until this ship appeared, not only confounding individual humans whose lives had been calm, predictable, and prosperous in their isolation – but suddenly giving atevi twohuman presences to deal with, when they'd only in the most recent years reached a thoroughly peaceful accommodation with the humans on the island off their shores.

So, one could imagine that the aiji in Shejidan, lord of the Western Association, quite reasonably wanted to know what was in those transmissions that now flowed between that ship and the earth station on Mospheira.

The paidhi wanted to know that answer himself. Something in the last twenty-four hours had changed in the urgency of his presence here – but he had no special brief from the President or State Department to provide those answers, not one damned bit of instruction at least that he'd been conscious enough to remember. He did have a firsthand and still fresh understanding that if things went badly and relations between humans and atevi blew up, this side of the strait would not be a safe place for a human to be: humans and atevi had already fought one bloody war over mistaken intentions. He didn't know if he could single-handedly prevent another; but there was always, constantly inherent in the paidhi's job, the knowledge that if the future of humankind on Mospheira and in this end of the universe wasn't in his power to direct – it was damned sure within his power to screw up.

One fracture in the essential Western Association – one essential leader like the aiji of Shejidan losing position.

One damned fool human with a radio transmitter or one atevi hothead with a hunting rifle – and of the latter, there were entirely too many available on the mainland for his own peace of mind: guns meant food on the table out in the countryside. Atevi youngsters learned to shoot when human kids were learning to ride bikes – and some atevi got damned good at it. Some atevi became licensed professionals, in a society where assassination was a regular legal recourse.

And if Tabini-aiji lost his grip on the Western Association, and if that started fragmenting, everything came undone. Atevi had provinces, but they didn't have borders. Atevi couldn't understand lines on maps by anything logical or reasonable except an approximation of where the householders on that line happened to side on various and reasonable grounds affecting their area, their culture, their scattered loyalties to other associations with nothing in the world to dowith geography.

In more than that respect, it wasn't a human society in the world beyond the island of Mospheira, and if the established atevi authority went down, after nearly two hundred years of building an industrial complex and an interlinked power structure uniting hundreds of small atevi associations —

– it would be his personal fault.

The plane broke through the cloud deck, rain making trails on the window, crooked patterns that fractured the outward view of a city skyline with no tall buildings, a few smokestacks. Tiled roofs, organized by auspicious geometries atevi eyes understood, marched up and down the rain-veiled hills.

The wing dipped, the slats extended as they passed near the vast governmental complex that was his destination: the Bu-javid, the aiji's residence, dominating the highest hill on the edge of Shejidan, a hill footed by hotels and hostels of every class, a little glimmer of – God – audacious neon in the gray haze.

Witness atevi democracy in plain evidence, in those hotels. In the regular audiences and in emergency matters, petitioners lodged there, ordinary people seeking personal audience with the ruler of the greatest association in the world.

In their seasons of legislative duty, lawmakers of the elected hasdrawad occupied the same hotel rooms, with their security and their staffs. Even a handful of the tashrid, those newly ennobled who lacked ancestral arrangements within the Bu-javid itself, found lodging for themselves and their staffs in those pay-by-the-night rooms at the foot of the hill, shoulder to shoulder with shopkeepers, bricklayers, numerologists and television news crews.

With the long-absent emergency hanging literally over the world, the hotels down there were crammed right now and service in the restaurants was, bet on it, in collapse. The legislative committees would all be in session. The hasdrawad and the tashrid would be in full cry. Unseasonal petitioners would barter the doors of the aiji's numerous secretaries, seeking exception for immediate audience for whatever special, threatened interests they represented. Technical experts, fanatic number-counters and crackpot theorists would be jostling each other in the halls of the Bu-javid – because in atevi thinking, all the universe was describable in numbers; numbers were felicitous or not felicitous: numbers blessed or doomed a project, and there were a thousand different systems for reckoning the significant numbers in a matter – all of them backed by absolute, wild-eyed believers.

God help the process of intelligent decisions.

The runway was close now. He watched the warehouses and factories of Shejidan glide under the wing: factory-tops, at the last, rain-pocked puddles on their asphalt and gravel, a drowned view of ventilation fans and a company logo outlined in gravel. He'd never seen Aqidan Pipe & Fittings from file ground. But it, along with the spire of Western Mining and Industry and the roof of Patanandi Aerospace, was the reassuring landmark of all his homecomings to this side of the strait.

Curious notion, that Shejidan had become a refuge.

He hadn't even seen his mother this trip to Mospheira. She hadn't come to the hospital. He'd phoned her when he'd gotten in – he'd gotten time for three phone calls in his hospital room before they knocked him halfway out with painkillers and ran him off for tests. He distinctly remembered he'd phoned her, spoken with her, told her where he was, said he'd be in surgery in the morning. He'd told her, playing down the matter, that she didn't need to come, she could call the hospital for a report when he came to. But he'd honestly and secretly hoped she'd come, maybe show a little maternal concern.

He'd phoned his brother Toby, too, long distance to the northern seacoast where Toby and his wife lived. Toby had said he was sure he was all right, he was very glad he'd turned up back on the job under the present conditions – which the paidhi couldn't, of course, discuss with his family, so they didn't discuss it; and that had been that.

He'd called Barb last: he'd known beyond any doubt that Barb would come to the hospital, but Barb hadn't answered her phone. He'd left a message on the system: Hi, Barb, don't believe the news reports, I'm all right. Hope to see you while I'm here.

But it had been just a Departmental staffer leaning over his bed when he woke, saying, How are you feeling, Mr. Cameron?

And: We really hope you're up to this ....

Thanks, he'd said.

What else could you say? Thanks for the flowers?

Wheels touched, squeaked on wet pavement. He stared out through water-streaked windows at an ash-colored sky, a rainy concrete vista of taxiways, terminal, a functional, blockish architecture, that could, if he didn't know better, be the corresponding international airport on Mospheira.

A team from National Security had taken charge of his computer while he was down-timed on a hospital gurney; State Department experts and the NSA had probably walked all through his files, from his personal letters to his notes for his speeches and his dictionary notes, but they'd had to rush. He'd expected, even knowing his recall would be soon, at least one day to lie in the sun.

But something having hit crisis level, when the security team had picked him up at the hospital emergency desk to take him to his office, they'd handed his computer back to him and given him thirty minutes in his office on the way to the airport – thirty whole minutes, on the systemic remnant of anesthetic and painkillers, to access the files he expected to need, load in the new security overlay codes, and dispose of a request from the President's secretary for a briefing the President apparently wasn't going to get. Meanwhile he'd sent his personal Seeker through the system with all flags flying, to get what it could – whatever his staff, the Foreign Office, the State Department and his various correspondents had sent to him.

In the rush, he didn't even know what files he'd actually gotten, what he might have gotten if he'd argued vigorously with the State Department censors, or what in the main DB might have changed. They'd had an uncommonly narrow window of authorization for their plane to enter atevi airspace, itself an indicator of increased tensions: they'd driven like hell getting to the airport, bumped all Mospheiran local aircraft out of schedule, as it was, and when he'd just gotten served a fruit juice and they'd reached altitude, where he planned to work for his hour in the air, he'd dropped off to sleep watching the clouds.

He'd thought – just rest his eyes. Just shut out the sunlight, such a fierce lot of sunlight, above the clouds. He wasn't sure even now the damned painkiller was out of his system. Things floated. His thoughts skittered about at random, no idea what he was facing, no solid memory what the man from the Department had told him.

The plane made the relatively short taxi not to the regular debarkation point but to the blind, windowless end of the passenger terminal. He managed to get unbelted, and as the plane shut down its engines, cast an expectant look at the attendants for help with his stowed luggage, and gathered himself up carefully out of the seat.

One attendant pulled his luggage from the stowage by the galley. He defended his computer as his own problem, despite the other attendant's reach to help him with that. "The coat, please," he said, and turned his back for help to get it on – one slightly edge-of-season coat he'd had in reserve in Mospheira, atevi-style, many-buttoned and knee-length. He got the one arm in the sleeve, accepted the other onto his immobile shoulder – the damned coat tended to slide, and if it were Mospheira, in summer, he wouldn't bother; but this was Shejidan and a gentleman absolutely wore a coat in public.

A gentleman absolutely took care to have his braid neatly done, too, with the included ribbons indicative of his status and his lineage; but the atevi public would have to forgive him: he'd had no one but the orderly at the hospital to put his hair in the requisite braid. He'd intended to protect it from the seat-rest during the flight, but after his unintended nap, he didn't know what condition it was in. He bowed his head now and managed one-handed to pull it from under the coat collar without losing the coat off his shoulder, felt an unwelcome wisp of flyaway by his cheek and tried to tuck it in.

Then he picked up his computer, eased the strap onto his good shoulder and made his unhurried way forward, an embarrassingly disreputable figure, he feared, by court standards.

But he'd gotten here, he hoped withthe files he needed to work with, and he hoped to get to the Bu-javid without undue delay and without public notice. If everyone who was supposed to communicate had communicated and if the aiji hadn't been in nonstop meetings, he should have a car waiting as soon as they moved the ladder up. It thundered, sounding right overhead, and the paidhi prayed that he at least had a car waiting.

He had to remember, too, that he was now leaving the venue where seats and tables and doorways fit people his size: the stairs out there had a higher rise, and he was, lacking the use of one hand, feeling chill and rather petulantly fragile at the moment.

"Thank you," he said to the attendants who opened the aircraft door. The staircase was moving up – notthe canopied portable, much less the covered walk: it bumped into contact, rocking the plane, and one attendant set his luggage out on the rainy landing at the top of a shaky, rain-wet, metal ladder.

No car. It wasn't going well. Everything had the feeling of haste exceeding planning. Wind-driven mist whipped through the open doorway, and he was ready to go back where it was dry, when a van with the airport security logo whisked from around the nose and braked just short of an epic puddle, so abrupt an arrival his security-conscious nerves had twitched, his whole body poised to fling himself backward.

"Take care, sir. The steps are higher."

"I know. I know, thank you, though. Good flight. Thank you so much. Thank the crew." He raised a shoulder to keep the computer strap in place and felt a sudden, perilous challenge of balance as he ventured out onto the stairs into the wind-borne spatter of rain. He grabbed the rail, shoulder still canted, struggling not to let the computer strap slip off.

The van's side door opened. An armed atevi, a brisk dark giant in the silver-studded black of Bu-javid security and the aiji's personal guard, exited the van and raced up the steps, making the stairs rattle and shake under atevi muscle.

"Nadi Bren!" a woman's voice hailed him, and a bleak day brightened.

"Jago!"

"I'll take that, nadi Bren. Give me your hand." Two steps below him, Jago stood eye to eye with him. She seized the computer strap on his shoulder, took it from him in relentless courtesy and captured his chilled white hand in her large black one, competency, solidity in a thunderous, wind-blown world. He had no doubt at all Jago could catch him if he slipped – no doubt that she could carry him down the steps in one arm if she had to.

And on his tottery, rain-blasted way down the ladder, he was not at all surprised, having encountered Jago, to see Banichi exit the van more slowly to welcome them.

He was glad it was them. God, he was relieved —

He was so relieved he had a dizzy spell, forgot the scale of the next step, and if Jago hadn't had an instant and solid grip under his good arm he'd have gone down for sure.

"Careful," she said, hauling him back to balance. "Careful, Bren-ji, the steps are slick."

Slick. Lightning flashed overhead, whiting out detail, glancing off the puddle. He reached the bottom rubber-legged as Banichi stepped out of the way for him and for Jago, who helped him into the van and climbed in after.

Banichi brought up the rear, swung up and in and slammed the door, sealing out the rain and the thunder. Like Jago, black leather and silver studs, black skin, black hair, gold eyes, Banichi fell into the available door-side seat, saving his leg from flexing, Bren didn't fail to note, as he settled next to the far window.

"Go," Jago said to the driver.

"My luggage," Bren protested as the van jerked into motion.

"Tano will bring it. There's a second van."

Tano was another familiar name, a man he was exceedingly glad to know was alive.

"Algini?" he asked, meaning Tano's partner.

"Malguri Hospital," Banichi said. "How areyou, Bren-ji?"

Far better than he'd thought. People were alive that he'd feared dead.

But other people, good people, had died for mistaken, stupid reasons.

"Is there word —" His voice cracked as he leaned back against the seat. "Is there word from Malguri? From Djinana? Are they all right?"

"One can inquire," Jago said.

He hadn't remotely realized he was so shaky. Maybe it was the sudden feeling of safety. Maybe it was the haste he'd been in back on Mospheira to gather everything he needed. His mind wandered back into the web of atevi proprieties, lost in the mindset that didn't allow Banichi or Jago the simple opportunity to inquire about —

Atevi didn't have friends. God, God, wipe the word from his mind. Twenty-four hours across the strait and he was thinking in Mosphei', making psychological slips like that, a dim-witted slide toward what was human, when he was no longer in human territory.

The van swerved around a corner, and they all leaned. It was summer in Shejidan, but they seemed to have the heater on, all the same, because the clammy chill was gone. He leaned his head back on the seat, blinked his stinging eyes and asked, as the straightening of the course rolled his head toward Banichi, "Are we taking the subway out, or what?"

"Yes," Banichi told him.

Banichi hadn't come up the ramp after him.

"The leg, Banichi?"

"No detriment, nand' paidhi. I assure you."

To his efficiency, Banichi meant. Back on mainland soil and he'd assigned Jago a diplomatically touchy inter-staff inquiry and insulted Banichi's judgment and competency. He didn't know how he could improve on it.

"Ignore my stupid questions," he said. "Drugs. Just got out of hospital. I took a painkiller. I shouldn't have."

"How did the surgery go?" Jago asked.

He tried to remember. "I forgot to ask," he admitted, and didn't know why he hadn't, except that in some convoluted, drug-hazed fashion he'd taken for granted he was going to have a shoulder that worked. He hoped so.

Hell, it felt as if he'd picked up where he'd left his life yesterday – was it yesterday? – and everything about Mospheira was a passing dream. It felt good, it felt safeto be back with these two. He wasn't tracking outstandingly well on anything at the moment, except that between these two individuals he felt he could handle anything.

If these two were here, he knew that Tabini, none other, had sent them.

The van's tires made a wet sound on the airport pavement. He let his eyes shut. He could let down his propriety with these two, who'd lived intimately with him, who'd cared for him when he was far less than self-possessed – and he'd know even blind that he was in Shejidan, not Mospheira. He knew by the smells of rain-wet leather and the warmth of atevi bodies, the slight scent that attended them, which might be perfume, or might be natural – it was an odd thing that he'd never quite questioned it, but it was pleasant and familiar, in the way old rooms and accustomed places were comfortable to find.

The van nosed down an incline, and he blinked a look at his surroundings, knowing where they were before he used his eyes: the ramp down into the utilitarian concrete of the restricted underground terminal. The aiji used it – the aiji and others whose safety and privacy the government wanted to guarantee.

He'd discovered a comfortable position in which to sit, good shoulder against the van wall. He truly, truly didn't want to move right now.

"I trust," he said, shutting his eyes again, "that there'll be a chance for me to rest, nadiin. I really, really hope to rest a while before I have to think or do anything truly critical."

Jago's fingers brushed his shoulder. "Bren-ji, we can carry you to the car if you wish."

The van braked to a halt. "No," he said, and remember ing that these two afforded themselves no weakness and rarely a sign of pain, he opened his eyes and tried to drag himself back to the gray concrete and echoing world. "I'll manage, thank you, nadiin, but, please, let's just wait for my luggage. I have every confidence in Tano. But it's only a single case. It has my medical records."

"We've orders, nadi," Banichi said.

Tabini's orders. No question. No dawdling even in a secure area. Possibly there had been some filing of Intent against his life, but most likely it was simply Tabini's desire to have the paidhi in place, under a guard he trusted, and to have one more ragged-edged problem off his mind.

Banichi opened the door and stepped down to the pavement, Jago got out after, taking the computer, and Bren edged across the seat and stepped down with less assurance, into their competent and watchful care.

The subway had its own peculiar atmosphere: oil, cold concrete and echoes of machinery and voices – like any station in the city system, like any in the continent-spanning rail that linked to the city subway; a connection which argued there could be a small risk of some security breach, he supposed, but no one came into this station without a security clearance, not the baggage handlers, not the workmen: cars didn't stop here.

Which meant there was no burning reason now, in his unregarded and probably uninformed opinion, that the paidhi couldn't stand about for half a minute and wait for his luggage – but considering the wobble in his knees and the disorientation that came buzzing through his brain with the white noise of the echoing space, he let himself be moved along the trackside at Banichi's best limping pace.

A pair of Bu-javid guards, standing outside on the platform, opened the door of the car – seemingly a freight-carrier – that waited for them. They were guards he didn't know, but clearly Banichi did, sufficiently that Banichi sent Jago into the car for no more than a cursory look before letting Bren inside.

It was residential-style furnishing inside the car, false windows inside curtained in red velvet. It was the aiji's own traveling salon, plush appointments, the whole affair in muted reds and beige, a complete galley, soft chairs – Bren let himself down in one that wouldn't swallow him in its cushions, and Jago, setting the computer down, went immediately to open the galley, asking him did he want fruit juice?

"Tea, nadi, if you please." He still felt chilled, and his ears had felt stuffed with wool since the change in altitude. Tea sounded good. Alkaloids that atevi metabolisms didn't mind at all in ordinary doses were especially common in herbal teas and concentrated in some atevi liquor, a fact he'd proved the hard way: but Banichi's junior partner wouldn't make mistakes like that with her charge. He shut his eyes in complete confidence and only opened them when Jago gently announced the tea was ready, the train was about to couple the car on, and would he care for a cup now?

He would. He took the offered cup in his hand, as Banichi, having made it aboard, shut the outside door and went on talking to someone, doubtless official, on his pocket-com.

Jago cradled her cup against the gentle bump as the coupling engaged. "We're a three-car train," Jago said, settling opposite him.

"Tano's made it on," Banichi said as he came up and joined them. "Station security wouldn't let him in this car. I did point out he's in the same service, little that penetrates the minds in charge."

Bren didn't worry that much about his luggage at the moment. Climbing up the high step to the car had waked up the pain in his shoulder.

But after half a cup of tea, and with the train approaching the terminal in the Bu-javid's lower levels, he recovered a wistful hope of homecoming, his own bed – if security afforded him that favor.

"Do you think, nadiin, that I'll possibly have my garden apartment back?"

"No," Banichi said. "I fear not. I'll inquire. But it's a fine view of the mountains, where you're going."

"The mountains." He was dismayed. "The upper floor? – Or a hotel?"

"A very fine accommodation. A staunch partisan has made you her personal guest, openly preferring the aiji's apartment for the session."

A staunch partisan. Tabini-aiji's staunch partisan. Tabini's apartment.

The train began braking. Jago extended her hand for the cup.

Damiri?

Tabini's hitherto clandestine lover? Of the Atigeini opposition?

My God. Damiri had declared herself. Her relatives were going to riot in the streets.

And a humanfor Tabini's next-door neighbor, even temporarily, lodged in an area of the Bu-javid only the highest and most ancient lords of the Association attained?

A human didn't belong there. Not there – and certainly not in a noble and respectable lady's private quarters. There was bound to be gossip. Coarse jokes. Detriment to the lady and the lady's family, whose regional association had openly opposed Tabini's policies from the day of his accession as aiji-major.

Slipping indeed. He must have let his dismay reach his face: Banichi said, as the brakes squealed, "Tabini wants you alive at any cost, nand' paidhi. Things are very delicate. The lady has made her wager on Tabini, and on Tabini's resourcefulness, with the dice still falling."

Baji-naji. Fortune and chance, twin powers of atevi belief, intervenors in the rigid tyranny of numbers.

The car came to rest.

The doors opened. Banichi was easily on his feet, offering a hand. Bren moved more slowly, promising himself that in just a little while he could have a bed, a place to lie still and let his head quit buzzing.

Jago gathered up his computer. "I'll manage it, Bren-ji. Take care for yourself. Please don't fall."

"I assure you," he murmured, and followed Banichi's lead to the door, down again, off the steps, into what he assumed was tight security – at least as tight as afforded no chance of meetings.

"Bren Cameron," a voice echoed out, a female voice, sharp, human and angry.

" Deana?" Deana Hanks didn't belong in the equation. She'd been out of communication, the fogged brain added back in; he'd asked that her authorizations be pulled by the Foreign Office, and he'd assumed – assumedshe'd gone home. His successor had nolegitimate business on the mainland.