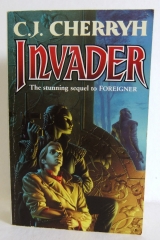

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

From a third of the seats filled there was a sudden abundance of legislators in the aisles, moving with some purpose, and he was not at all surprised, once that influx had found seats, that Tabini-aiji arrived by the same entry he'd used – but Tabini walked to the fore of the chamber. The gallery was jammed with observers, and while Jago and Tano stood steadfastly on guard near Bren, Tabini walked to the podium.

"Nand' paidhi," Tabini said, the speakers echoing out over both halls.

He got up, picked up the computer Jago had set near him, and began his trek down the aisle while Tabini received the standing, silent courtesy of the joint houses, and then declared that the paidhi would, for the first time in this administration, address the houses of government and the provinces conjointly, "to provide expert information on the event in the heavens."

He came up to the secondary microphone with no other fanfare, bowed to Tabini, bowed to the tashrid, to the hasdrawad, and set the computer down.

"Ladies and gentlemen of the Association," was the correct address, and, "Nand' paidhi," he heard back, as the members bowed to him in turn, then sat down.

He drew an insufficient breath, and found a convenient place to lean a supporting arm on the lower rails of a speaker's platform far too tall for him.

A sea of dark, listening, variously expectant faces confronted him.

"A long time ago," he began, "Nadiin, a ship set out from a distant world, intending to build a space station at a place they thought they were going to live. But some accident sent the ship out of sight of all the stars the navigators knew, into a place so heavy with radiation it was deadly to anyone working outside the hull. Very many of the crew died gathering the resources they had to have to take the ship to safety. The workers who were only passengers on this mission had no skills to save the ship: they voted the ship's crew extraordinary privilege and power so long as it was ship's crew who went outside the hull."

Atevi audiences didn't emote in a formal presentation. They sat. They kept impassive faces and absolute, respectful silence. They didn't cue a speaker what way they were thinking, or whether they were understanding, or whether they wanted to shoot the speaker. Atevi audiences just listened, disconcertingly so.

But the reason for the granting of rank and privilege was absolutely important to atevi thinking. And while privilege could arise from ancestral merit, it had to have constant merit, or it was suspect: thatwas the groundwork he was laying. Deliberately.

"Nadiin," he said, and fought for breath over the constriction of the tape around his ribs, damnably unforgiving of the fact the wearer was scared, needed to project his voice, and needed more air. "Brave people mined the fuel they needed to fly the ship to a more favorable and healthful place, which they had to choose on very little data. This world —" One avoided more precise cosmology. It had to come soon. Just, please God, not tonight. "This world was promising. But once they entered orbit here, they were vastly upset to learn it was an inhabited planet. They'd spent all their fuel. They'd lost so many lives they were growing fragile as a community. The ship crew wanted to withdraw to the fourth planet from the sun and build a station in orbit, thinking it then might be a long time before atevi discovered human presence – but after such a dangerous journey —"

Another pause for air, and he still had no reaction at all, good or bad, to what was mostly old information, with insights that weren't in the previous canon. "After such a terrible journey, nadiin, and so many lives lost, people were afraid of travel and harsh, unknown environments. They reasoned if they built their home in orbit around a life-bearing world, and if something went wrong in space, there was the planet below as a last resort. They saw that atevi were civilized and advanced – their telescopes told them so. They felt much safer where they were, and they voted against the ship's crew."

"But some Mospheirans say the crew of the ship was anxious to maintain the reason for their rank and privilege, and that was their real reason for wanting to take the ship back into deep space."

"Some argue, no, it was a true concern for disturbing atevi lives."

"Still others say that they simply were a space-faring people and saw themselves constricted by this long time at dock."

"But for whatever reason, the crew of the ship wanted to leave and wanted fuel. The workers' representatives opposed more expenditure of effort for the ship in a venture in which they saw no advantage for themselves. That was the point at which the association on the station truly began to fragment."

"Some said they should go down to the planet and establish a base there."

"Some said all resources should go to the station as a permanent human home in orbit, and that they wouldn't divert resources to a landing or to the ship for any new venture."

"Now there were three factions, and the situation demanded compromise."

"The ship sided with the workers who wanted to maintain the station, because they needed the station for a dock and a source of repair and supply; but taking the ship out into deep space, which was their highest priority, demanded an immense amount of the resources the station wanted for itself. The workers who wanted to land on the planet switched sides and voted with the ship's crew, at least one human scholar suspects, in return for secret assurances the spacefarers wouldn't let the station dwellers block their activities."

"The human community became a nest of intrigue as the new sub-associations pulled each in their own directions. The ship sided with the would-be colonists to get the resources it needed —"

"But, because in this three-way standoff, the pro-Landing people couldn't get funding or resources for advanced landing craft, no one believed they could land, especially since the Pilots' Guild refused to fly the designs they had for a landing craft – or – the Landing faction began to suspect, any design they would ever come up with."

"So – that group built landers with old technology that didn't need Guild pilots. In effect, they fell toward the planet and parachuted in, the petal sails of the old account. Mospheira looked to them to have a lot of vacant land, and they thought if there were trouble, it would be easy to live in the north of the island and make agreements with atevi to the south in what they thought was an island government."

Atevi calm cracked in scattered laughter. Certain members clearly thought it was a joke. It wasfunny, if lives on both sides hadn't paid for it; he was relieved: they were following his logic. They were understanding this very critical point of human behavior.

"It actually got worse, nadiin. The Guild thought the Landing would lose credibility, either operationally, due to crashes, or practically, in atevi unwillingness to allow them on the planet."

"But the first down landed safely. The world seemed perfectly hospitable. Even the station workers and the Guild now believed, since atevi hadn't objected, that all the empty land on the planet was unowned land, where they'd bother no one."

"That, nadiin, was the situation when the ship left. That's the last it knows. It knows nothing about the war, it knows nothing about the Treaty, it knows nothing about the abandonment of the station and it knows nothing about the reasons that bar humans and atevi from dealing directly. You are faced, nadiin, in my estimation, with both marginal good will from the ship and an ignorance equaling the ignorance of my direct ancestors in that year, in that day, in that hourof their departure."

"Nadiin, humans in the early days had no idea how they'd disturbed atevi life – they didn't understand they'd transgressed associations when they'd followed a geographical feature they believed was a boundary. They blundered through association lines, they built roads with no remote thought that they were creating a problem, they brought technology to one association with no remote idea they were altering balances, and, baji-naji, there are humans on Mospheira who stillcan't make that leap out of their own mentality and into atevi understanding, just as there are doubtless atevi who dismiss human behavior as complete insanity."

"But we have that ship up there that left a planet with atevi just developing steam engines. Now it looks down on railroads, cities, airports, power plants alike on Mospheira and the mainland, and sees nothing there to tell it what the agreements are that let this happen peacefully."

"I report to my great regret a hitherto harmless minority of officials in my government, a faction who take the demands of cultural separation in the Treaty agreement as a major item of their belief: we call them separatists, but some of them go much further than mere cultural preservation, and believe that humans should exclude atevi from space, which, along with advanced technology, they view as their exclusive heritage. They may see the ship as a chance for them to recapture the past. They may try to urge the ship's crew that I'm a gullible fool and that they're being threatened by atevi, whom they have always apprehended as seeking to destroy human culture."

"The most serious danger is not the ship. It's in offering a reckless minority of my own people on this world the belief that they have alternatives to negotiation with atevi ifthey can mislead the crew of the ship to their own opinions, and particularly if they can get a presence of their own persuasion brought up to the station."

"I've not completely traced the origins of the human separatist movement, or analyzed its membership: in fact, most won't admit to it. But recall that the station had to be abandoned because of failing systems and lack of resources, that the faction which wanted the station maintained is on this planet with us, and I think likely the pro-space movement among humans logically contains those who wish we'd stayed in space. They in particular may be lured into an association with the separatists because the separatists could offer them a return to the station. It involves conjecture on my part, but I fear an association may suddenly be possible involving these two groups with a human return to space as its unifying purpose. I am utterly, morally, opposed to seeing a handful of Mospheirans go back into space with borrowed technology and entering into agreements that convey political power again on the ship crew. The space program this world develops must be jointly human and atevi, and control of the station must be jointly human and atevi."

"I know that some atevi also ask, Why human presence at all? And, yes, ideally no human would ever have come down to this planet; but since humans haveno other planet in all of space around which to center their activity, and since humans are in orbit around this planet, it's reasonable that the ship, representing many factors of higher technology than any this world can manage right now, is up to activities that will inevitably involve this world on which atevi live. For that reason it becomes imperative that atevi secure a vote in human space activities."

"Nadiin, I do notintend to let a minority of humans put themselves forward as the only voice speaking for this planet. I wish to put forward the Treaty as the operative association of humans and atevi."

"I am willing to translate atevi voices to the ship, in order to see to it that whatever the ship wants or whatever the Mospheiran President or Mospheiran factions of whatever nature may do, the ship will not be conducting business in the same ignorance that led to the War of the Landing."

"I do know humans, nadiin, from the inside. I can assure you as I know the sun will rise tomorrow, that the ship crew won't be nearly as naive about Mospheira's humans as they may be about atevi. It's going to be very hard for any Mospheiran faction to persuade the ship that they're without ulterior motives, and very hard for any faction on Mospheira to persuade the ship to any course, not alone because the ship will suspect factionalism, but because the ship itself may have internal factions whose siding with one faction or the other on Mospheira may absolutely paralyze decision and produce new sub-associations with the potential for truly dangerous compromises."

"For that reason I foresee that the human government on Mospheira will respond to evidence of division among atevi with paralytic inaction on the part of the government, frenetic activity on the part of those out of power, and no rational decision will result."

"I therefore recommend, nadiin, that atevi speak with one voice when they speak to humans on the ship and on Mospheira, that your inner divisions and debates remain strictly secret, and that you treat Mospheira and the ship as two separate entities until they themselves can speak with one voice. I recommend you claim, not demand, claim as a factan equal share in the space station… for a mere beginning."

"I recommend that you speak to the ship directly and soon. I am the paidhi the Treaty appointed to deal between Mospheira and the atevi of the Western Association. I ask the Association to appoint me paidhi also to deal with the ship. This triangular arrangement —" one was never without awareness of the all-important numbers "– places the Western Association on equal footing with Mospheira, who has already delegated spokesmen to deal with the ship."

"The ship knows it must understand Mospheira as well as atevi before it can be confident of its actions. The permutations of advantage and disadvantage in this arrangement are complex, and I am convinced that atevi can secure equal advantage for themselves, particularly by securing agreements with both the elected government of Mospheira andwith the ship's authority. Again, a trilateral stability."

"I hope for your favorable consideration of the matters I've brought before you, my lords of the Association, most honorable representatives of the provinces, aiji-ma. Thank you. I stand for questions."

There it goes, he thought, made the requisite formal bow, and suffered a shortness of breath, a sweating of the palms, and a fleeting recollection, of all things, of Barb on the ski run: Barb laughing, all that white, and the whole world stretching on forever – that time, that chance, that life —

Gone – maybe gone for good, with the moves he was making.

And he had, with that disoriented sense of what now? and where now? a consuming fear that he hadn't been entirely dispassionate in his judgment, when he most, God help him, needed to be.

Slowly, in the way of atevi listeners, a murmur of comment had begun, then:

"Nand' paidhi." It was a distinguished member of the tashrid, rising to question, in the custom of the chambers. "Has your President assigned you this action against human interests in some sense of numeric balances?"

An intercultural minefield. Had the human government found inharmonious numbers for the whole situation or did it wish to create them for atevi? And the gentleman of the tashrid damn well knew humans didn't count numbers: he was playing to rural atevi paranoia and he was playing straight to the television.

So could he.

"Lord Aidin, I by no means see Mospheiran and atevi best interests as conflicting. Consider, too, my government returned me, in a crisis and under medical circumstances which clearly justified my staying on Mospheira for weeks – cooperating because Tabini-aiji requested my return. They know that if there weren't a paidhi, or if the aiji should break off relations with the paidhi-successor, as the aiji has done, no communication at all would be possible between atevi and humans. Had Mospheira wished to hold me hostage and cut off communication they might have done so. My return, literally rushing me from surgery to the airport, signals a very strong human desire to maintain communication with the mainland and their firm acknowledgment that the aiji is the ruler of the Western Association."

Lord Aidin sat down, having planted what he'd chosen to plant, all the same, for minds set on number conspiracies, damn him; but he'd gotten his own little drama in front of the cameras, too.

Then, in the evenhanded alternation of questions, a member of the hasdrawad rose, a woman he didn't know, with an abrupt: "Then who, nadi, sent Hanks-paidhi?"

Nadi, to an official speaker on the platform, was not fully respectful, and it roused a rare stir in the chambers – a sharp look from Tabini.

He answered, nonetheless, to an ateva who might have either been offended by Hanks, or leaned to Hanks as a source and now found herself embarrassed in Hanks' lack of authority:

"By the Treaty, nadi, there is only one paidhi. And, nadi, nadiin, Hanks is my successor-designate, doubtless confused by the rapidity of events. She should have received a recall order, but events have moved perhaps faster than ordinary lines of communication. She has as yet received no such orders, and feels it incumbent on her to stay until she does. I've requested of the aiji to allow her presence temporarily. If you have doubt of the delivery of your messages to the paidhi during this transition, please don't hesitate to resend. No slight is intended, nadi."

So, so quietly posed. It was really the most byzantine atevi warning he'd ever managed to deliver, and he was quite satisfied with his performance – injecting into the atevi consciousness at basement level an insight into human decision-making, and not just the hasdrawad and the tashrid, thanks to the television cameras. He had had the option, being only human, of ducking the after-address questions ordinary for an atevi speaker; but he saw those cameras, and daunting as they'd been at the outset, he'd managed, sure in his own mind it was useful for atevi out in the provinces to see the paidhi and get a sense of his face, his reactions, his nature.

"Nand' paidhi." It was a conservative member of the tashrid, rising to speak in turn. "What do youbelieve the ship is doing up there?"

Old, old, lord Madinais, blunt, and very common-man in his approaches. A respected grandfather, he always thought of the man; but that misapprehended the real power Madinais had, through seniority in a network of sub-associations many of which werecommon-man, broad-based and powerful.

"Lord Madinais, I can only conjecture: I think the ship broke down again. I think they've managed to fix it, get it running, and get back to what they hoped would be a thriving human community. It is thriving – but it's certainly complicated their position."

Dissident interests, not far from lord Madinais, had tried to kill Bren last week. But there was nothing personal in it.

"What about the trade rules?" a member of the hasdrawad shouted out. "What about the negotiations?"

"I don't think there'll be any progress in the trade talks until this ship question is settled, quite frankly, nadi. Although —"

Behind the glare of television lights someone else was on his feet, in the hasdrawad, and that wasn't by the rules.

Nerves twitched, hesitated at alarm – Fall down, his information told him; but, Possibly mistaken, his fore-brain was saying.

At that moment a body hit him like a thunderbolt from the casted side and a shot boomed out and echoed and reechoed in the chambers.

He was on his side, with a sore hip, a bump on the side of his head where he'd hit the podium, and a crushing atevi weight half on him – Tano, he was suddenly aware. He was grateful, was stunned and apprehensive: he didn't see Jago. But he didn't see damn much of anything but the base of the podium and Tano's anxious face looking out toward the chambers. He didn't even protest to Tano that he was in pain, Tano's attention being clearly directed outward for hostile movements – but by the buzz of talk and the tenor of voices in the chamber, he could guess there'd been at least one fatality, and that the crisis was done, meaning the fatality was the person who'd threatened the paidhi.

Confirmed, as Tano began to get to one knee.

The recipient of such devoted guardianship knew he should still keep his head down and better his position only with extreme care. But he hurt. Members and security alike were converging on the podium – Tabini himself among them, which surely meant it was safe to get up, and he began to, first with Tano's help, then with Tabini's, and last with Tabini's security holding his arm and being very careful of his bandages and the cast.

"I'm very sorry," he said, embarrassed, not realizing the microphone was on. It boomed out over the hall and provoked laughter. Provoked, more, the solemn, unison clapping of hands that was the atevi notion of formal applause —

They hadn't been sure he was alive. They were pleased that he was. At least – the majority seemed to be.

Clearly there'd been one vote to the contrary.

The network television clip showed Tano's tackle andtake-down, the sight of which sent repeated shocks through his nerves, and a house camera showed the gunman, who'd put a bullet into a thirteenth-century chandelier when Jago had put a bullet through his head. They ran it, ran it back and ran it again and again in slow motion.

Bren, elbow on the counter, put his knuckle in front of his mouth and tried to be objective. He'd seenshots fired before, he'd seen people hit, he'd felt the ground he was standing on jump to far heavier ordnance, and he told himself he ought to take it in an atevi sort of calm, safe as he was in the security station.

He didn't feel that at all.

The chief of Bu-javid security laid a black-and-white photo on the desk, showing him an older man, a man who ought to have had sense.

"The representative from Eighin," the chief said, "Beiguri, house of the Guisi. Any personal cause with this man or the Guisi?"

"No, nadi." His voice came out faint. He sat up, tried to ignore the pain of bruised ribs. "I know him – as politically opposed to the trade cities. He's never shown any – any such behavior. He's never been impolite ..."

Tabini was out in the chambers, vehemently pressing his point. There was talk of a vote on the paidhi's representation to the ship, a debate on an initiative to Mospheira. The police and Bu-javid security were rounding up Beiguri's aides and office staff.

The tape around the ribs was hell. He hoped Tano hadn't popped stitches, bone, or seams. He hurt. Tano kept hovering, worse than Jago, who hadn't used him for a landing zone; and Jago —

Jago was suffering the aftermath, he thought: the awareness how easily she might have missed that snap shot. She quivered with unspent energy and anger, she hugged it in with arms clenched across her chest, and she wanted, Bren was sure, to be out there scouring the representative's office for what the junior security agents were most likely going to lay all too-casual hands on, in Jago's probably accurate estimation.

Jago wasn't senior in her own team. She was probably also worrying about Banichi's opinion. Or Banichi's whereabouts.

Or knewwhere Banichi was. And still worried.

More investigators came into the security station, reporting that the death office had taken the body away. A respectable and sensible man, a father of children, an elected representative of his province, had died trying to take the paidhi's life.

Bren shivered. Tano set hands on his shoulder and argued with the police that the paidhi would be perfectly safe upstairs in his own bed, and should be there.

"The aiji —" the chief of police began.

"We have the aiji's orders," Jago said shortly, taking her eyes from the constant replay. "And we have the responsibility, nand' Marin. It's been a very long day for him, and yesterday was longer. If the paidhi wishes to go upstairs —"

"The paidhi wishes," Bren said. He put himself on his feet as a way to accelerate matters. He wanted his room, he wanted his bed, he wanted quiet.

And he'd seen enough of the television replays.

He'd not have given anything for his chance of enduring police questions and playback after playback of the event, which assumed a surreal slow motion in his mind.

But after deciding one impossible thing after the other was the order of the hour, he had to do it, that was all. The next walk, Jago assured him, was only down to the lift – the press was excluded from this area, under special order – Tabini-aiji would handle the reporters in a news conference to follow his speech, and upstairs to his room and his bed was the direct order of business.

He made the lift, found himself with Jago and Tano alone in the car, and gratefully collapsed back against the wall. Tano was quiet; Jago was still in a glum, angry mood.

"Thank you," he said to her and Tano. He wasn't certain he hadmanaged somehow to express that.

"My job, nadi," Jago muttered, somewhat curtly, if a human could judge. If a human could judge, Jago was distracted in her own glum thoughts, maybe about Banichi's whereabouts, and the fact she'd had to peg a risky shot clear across, God help them, the halls of government. Maybe she'd gotten a reprimand from senior security, he wasn't sure.

It more than shook him. It whited out his logic about the situation. He realized Jago still had his computer, was still carrying it. Jago didn't make mistakes. Jago had had custody of his computer in the instant she was killing a man – and hadn't lost track of it.

More than the paidhi could say, who'd lingered on his feet analyzing why a man had risen out of turn – stood there, like a fool, and put Jago to making that desperate shot.

The lift let them out on the third level, and they walked the hall of porcelain flowers: ordinary homecoming, quite as if he were coming back from a day at the office, he thought in dazed detachment, standing at the door which Jago had to open with her device-disabling key.

The other side, in the pale, gilt foyer, the soul of atevi propriety, Saidin was there to take his coat.

"Just bed, nand' Saidin," he said. "I'm very tired." He deliberately didn't look at the message bowl. He didn't want to look.

"I think," he said, ticking down that mental list of things he'd reserved as priority, absolute must-dos, "I think I have to return the dowager's message tonight. Maybe we'd better talk very soon."

"You need your rest," Jago said severely.

"The dowager's goodwill is critical," he said. "Tomorrow morning would be a very good time. If there are repercussions – I can't let the dowager interpret my silence and my absence, Jago-ji. Am I mistaken? I believe I understand the woman."

Jago thought about it. Still wasn't pleased. Or was worried. "There is a danger, nadi. You know I can't go there."

"I don't think they're ready for open warfare. Therefore I'm safe."

Jago was not happy. Not at all. "I'll convey your message," she said. So Jago found his logic acceptable, atevi-fashion. And he thought he was right.

But the visible universe had shrunk to the immediate area of the foyer, and his sense of balance was uncertain – maybe relief, maybe just exhaustion. He felt quite shaky, quite short of breath in the constricting bandages.

"I'll go to bed, then," he said. "I think I've had a long day."

"Nand' paidhi," Tano said, and accompanied him.

He'd been amazed at his ability just to cross the speakers' platform without falling on his face.

But the bedroom was close, and he had not only Tano but a handful of female staff helping him, snatching up the laundry and murmuring that they were very glad the paidhi was unharmed. They'd seen the television. They were appalled at the goings-on.

He'd not had a review of his performance. "Nadiin," he said to them, "did you hear the things I said? Did they seem reasonable?"

"Nand' paidhi," one said, clearly taken aback, "it's not for us to offer opinion."

"If the paidhi asked."

"It was a very fine speech," one said. " Baji-naji, nand' paidhi. I don't understand such foreign things."

Another: "It was very risky for your ancestors to come down here."

And a third: "But where is this dangerous place, nand' paidhi? And where is the human earth? And where has the ship been?"

"All of these things, I wish I knew, nadi. The paidhi doesn't know. The wisest people on Mospheira don't know."

A servant lifted her hand, encompassing all things overhead. "Can't you find it with telescopes?"

"No. We're far, far, out of sight of where we came from. And there aren't any landmarks up there."

"Would you go there if you could, nand' paidhi?"

He faced a half dozen solemn female faces, dark, tall atevi, some standing, some kneeling, shadows in the light. He was the foreigner. He felt very much the foreigner in these premises.

"I was born on this planet," he said wearily. "I don't think I should be at home there, nadiin."

The faces gave him nothing.

"I regret," he said wearily, "I regret the matter tonight. He was a respectable man, nadiin. I regret – very much – he died. Please," he said, "Nadiin, I'm very tired. I have to go to bed."

There were multiple bows. The servants went away. But one turned back at the door and bowed. "Nand' paidhi," she said, "we hold to your side."

Another lingered and bowed, and in a moment more they were all back in the doorway, all talking at once, how they all wished him well, and how they hoped he would have a good night's sleep.

"Thank you, nadiin," he said, and began to arrange his nest of pillows to prop his arm as they went away into the central hall.

From which, in a moment, he heard a furious whispering about his white skin and his bruises, which he supposed he had more of, and remarking how he'd joked when Tabini had helped him up, and how he had very good composure.

Joked?

He didn't remember he'd done so well as that. He'd been scared as hell. He'd had to have Tano's help to get down the steps. He hadn't been able to walk up the aisle without his knees knocking – knowing – knowing the attempt was not only against him, who could be replaced, but against the entire established order. Atevi knew that. Atevi understood how much that bullet was supposed to destroy —