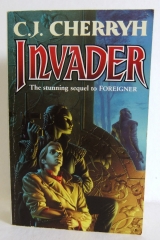

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

He'd thought he'd finished his duty. He thought he was going within the next few moments to his borrowed apartment and to his borrowed bed. The arm hurt. The tape around his ribs was its own special, knife-edged misery, growing more acute by the minute, and he couldn't do what Tabini wanted of him. He couldn't face it.

But Tabini was right about people dying while experts split semantic hairs; and God knew what rumors could be loose, or what Hanks could have said.

"Paidhi-ji, lives are at issue. The stability of the Association is at issue. The aiji of Shejidan can't askhelp of his associates. It would insult them. But so the paidhi understands, across the difficulty of our association —" Tabini couldn't imply his associates didn't share his needs – without implying they were traitors; Tabini was doing the paidhi's job again.

"I understand that," he said. "But I don't think I can walk far, aiji-ma." His voice wobbled. He felt irrationally close to tears. The shock of bombs in Malguri was still jolting through his nerves, the spatter of a close hit: not just dirt and rock chips, but fragments of a decent man he'd grown to like —

"It's just downstairs," Tabini said. "Just down the lift."

"I'll try," he said. He didn't even know how he was going to get to his feet. But Tabini stood up, and ignoring the pinch of tape around his ribs, Bren made it.

To do a job. To make sense of the incomprehensible, when the paidhi hardly conceived of the situation himself.

CHAPTER 4

Acable lift existed in the guarded back corridors of the aiji's apartment, a creaky thing, an antique of brass filigree and an alarming little bounce in the cables; but Bren rated it far, far better than a long walk. He went down with Tabini, with Banichi and with Tabini's senior personal guard, Naidiri, a two-floor descent into the constantly manned security post below, and out a series of doors which gave out onto a hall not available to the public.

By that back passage, one came to a small guard station with a choice of three other doors that were the secure access to separate meeting rooms which had, each, one outside general access. It was the closed route the Bu-javid residents used to reach the area where atevi commons and atevi lords met elbow to elbow, with all the vigorous give and take the legislatures employed.

On this route the lords of the Association, who held court at other appointed times, could reach their meetings safe from jostling by crowds and random, improper petitioners – and on this route one comparatively fragile and battered human could feel less threatened by collision in the halls.

More, the walk from the lift to the committee rooms was quite short, the room being, in this case, the small Blue Hall, which the Judiciary and Commerce Committees regularly used.

Jago and Tabini's second-rank security had preceded them down, were already at the doors, and briskly opened them on a noisy debate in progress among the twenty or so lords and people's representatives – the Minister of Finance shouting at the lord Minister of Transport with enough passion to jar the nerves of a weary, aching, and somewhat queasy human.

Perhaps they'd rather shout and finish the business they clearly had under consideration; and if he asked Tabini very nicely they might get him to his bed where he could fall unconscious.

But the debate died in mid-sentence, a quiet fell over the room, and lords and representatives of the Western Association bowed not just once to Tabini, but again to the paidhi, very clearly directing that courtesy at him.

Bren was taken quite aback – bowed before he thought clearly, and doubted then in muzzy embarrassment whether the second courtesy could be possibly aimed him at all.

"Nadiin," he murmured, confused and dizzy from the exertion, hoping only to make this short and not to have to answer more than a few questions.

Aides and pages hastened to draw out chairs and to settle him at the table, a flurry of courtesy, he thought, unaccustomed to the solicitousness and the attention, as if the paidhi looked to be apt to die on the spot.

Death wasn't an option, he thought, drawing a breath and feeling pain shoot through the shoulder, the wind from the air ducts cold on his perspiring face. But fainting dead away – that, he might dp. Voices came to him distantly, surreal and alternate with the beating of his heart.

"Nadiin," Tabini said quietly, having sat down at the other end of the table, "Bren-paidhi is straight from surgery and a long plane flight. Don't be too urgent with him. He's taxed himself just to walk down here."

Came then a murmur of sympathy and appreciation, the tall, black-skinned lords and representatives who set a lone, pale human at a childlike scale. A small tray with water and a small pot of hot tea arrived at Bren's place, as at every seat, then a small be-ribboned folder that would be, like the other such folders, the agenda of the meeting. He opened it, perfunctory courtesy. He wanted the water, but having settled at a relatively pain-free angle, didn't want to lean forward to get it.

"We were hearing the tape," lord Sigiadi said, the Minister of Commerce. "Does the paidhi have some notion, some least inkling, what the dialogue is between the island and the ship?"

"I haven't heard the tapes, nand' Minister. I'm promised to have them tomorrow."

"Would the paidhi listen briefly and tell us?"

The whole assembly murmured a quick agreement to that suggestion. "Yes," they said. "Play the tape."

At which point the paidhi suddenly knew, by the suspicious lack of special ceremony to Tabini's arrival, and by the equally elaborate courtesy to the paidhi, that the committee had almost certainly seen Tabini earlier in the same session.

And that the paidhi had just been, by a master of the art, sandbagged.

But it was a relief to sit still, at least, after a long day's jostling about. Even in the brief spell of sitting he'd had in Tabini's apartment, he'd exhausted himself, and the Council of Committees demanded nothing of him more than to sit in this late-night session and listen to the week's worth of tapes he urgently wanted to hear and get the gist of.

Which made it necessary to keep every reaction off his face, while men and women of the Western Association, themselves minimally expressive and capable of reading the little expression which high-ranking atevi did show in public, were watching his every twitch, shift of posture, and blink.

So he sat propped at his least painful angle, chin on hand, facial nerves deliberately disengaged – the paidhi had learned that atevi art early in his tenure – listening to the numeric blip and beep that atevi surveillance had picked up from Mospheira communications to the abandoned space station, machine talking to machine, the same as every week before the ship had arrived out of nowhere.

"This is computers talking," he murmured to the committee heads. "Either stored data exchange or one com puter trying to find the protocols of another. I leave the numbers therein to the experts, to tell if there's anything unusual. If the technician could go directly to the discernible voices —"

Then, with a hiccup of the running tape: " Ground Station Alpha, this isPhoenix. Please respond."

Even expecting it to happen, that thin voice hit human nerves – a voice from space, talking to a long-dead outpost, exactly as it would have done all those centuries ago.

But it was real, it was contemporary. It was the ship-dwelling presence orbiting the planet – a presence expecting all manner of things to be true that hadn't been true for longer than anyone alive could reckon.

"They're asking for an answer from the old landing site," he said, trying to look as blas6 as possible, while his pulse was doing otherwise. "They've no idea it's been dead for nearly two hundred years."

On that ship might even be – his scant expertise in relativity hinted at such – crew that rememberedthat site. The thought gave him gooseflesh as he listened through the brief squeal and blip, computers talking again: as he judged now, searching frequencies and sites for response from what optics had to tell the ship was an extensive settlement. He was about to indicate to the aide in charge of the tape to increase the playback rate.

"What are the numbers?" Judiciary asked. Loaded question.

"I believe they have to do with date, time, authorizations. That's the usual content."

Then he heard an obscure communications officer in charge of the all but defunct ground-station link answer that inquiry. " Say again?"

Which he rendered, and rare laughter touched the solemn faces about the table – surprise-reaction as humor being one of those few congruent points of atevi-human psychology; he was very glad of that reaction. It was an overwhelmingly important point to make with them, that humans had been as surprised as atevi; he hoped he'd scored it hard enough to get that fact told around.

That recorded call skipped rapidly through an increasingly high-ranking series of phone patches until he was experiencing the events, hewas waiting with those confused technicians – recovering the moments he'd missed while he was tucked away in remote places of the continent, and which, with Hanks sitting idle and unconsulted, atevi had had to experience without knowing what humans were saying.

After the first few exchanges, the realization that the contact was no hoax must have rocketed clear to the executive wing in less than an hour, because in a very scant chain of calls, the President of Mospheira was talking directly to the ship's captain.

"He's telling the ship's captain that he is in charge of the human community on Mospheira. The captain asks what that means, and the President answers that Mospheira is the island, that he is in charge…"

He lost a little of it then, or didn't lose it, just whited out on a wave of acute discomfort. He caught himself with a tightness around the mouth, and knew he had to keep his face calm. "Back the tape, please, just a little. The shoulder's hurting."

"If the paidhi is too ill —" Finance said; but stern, suspicious Judiciary broke in: "This is what we most need to hear, nand' paidhi. If you possibly can, one would like to hear."

"Replay," he said. The paidhi survived at times on theater. If you had points with atevi you used them, and going on in evident pain did get points, while the pain might excuse any frown. He listened, as the President maintained indeed he was the head of state on an exclusively human-populated island —

God. It already hit sensitive topics. He was no longer sure of his own judgment in going on when he'd had a chance to stop and think; he thought wildly now of falling from his chair in a faint, and feared his face was dead white. But pain was still a better excuse than he'd have later.

"The captain asks about the President's authority. The President says, 'Mospheira is a sovereign nation, the sta tion is still under Mospheiran governance. The ship's captain then asks, 'Mr. President, where isthe station crew?' – he's found the station abandoned – and then the President asks, 'Why – ' " He tried not to let his face change as he played the question through and through his head in the space of a few seconds, trying not to lose the thread that was continuing on the tape.

"What, nand' paidhi?" the Minister of Transportation asked quietly, and Bren lifted his hand for silence, not quite venturing to silence an atevi lord, but Tabini himself moved a cautioning hand as the tape kept running.

"The President of Mospheira complains of the ship's abandonment of the colony. The ship's captain suggested that the humans on Mospheira had a duty to maintain the station."

And after several more uneasy exchanges, in which he knewhe'd gotten well over his head in this translation, came the conclusion from the ship: " Then you don't have a space capability."

Bluntly put.

He rendered it: "The ship's captain asks whether Mospheira has manned launch capability." But he understood something far more ominous, and there seemed suddenly to be a draft in the room, as if someone elsewhere had opened a door. He sat and listened to the end of that conversation, feeling small chills jolt through him – maybe lack of sleep, maybe recent anesthetic, he wasn't sure.

No. Mospheira didn't have a space capability. Atevi didn't have, either. Not to equal that ship. And there was clear apprehension on atevi faces, expression allowed to surface; these heads of committee were steeped in atevi suspicion of each other – in a society where assassins were a legal recourse.

Damn, he thought, damn. He didn't know what he could do. The ship was notflinging out open arms to its lost brethren. The Foreign Office had called the exchanges touchy, and they were clearly that. His expression couldn't be auspicious or reassuring at the moment, and he hoped they attributed it to the pain.

"Cut the tape off," he said, "please, nadi. I think we have the essential position they're taking. The two leaders are signing off. I'll give you a full transcript as soon as tomorrow, I'm just —" His voice wobbled. "Very shaky right now."

"So," Tabini said in the silence that followed. "What does the paidhi think?"

The paidhi's mind was whited out in thought after tumbling thought. He rested his elbow on the chair, chin on his hand, in the one comfortable position he'd discovered, and took a moment answering.

"Aiji-ma, nadiin-ji, give me one day and the rest of the tapes. I can tell you… there is no agreement between the ship and Mospheira on the abandonment of the station. It seems an angry issue." Set the hook. Convince the committee heads they were getting the real story. Make them valuetheir information from the paidhi, not Hanks and not the rumor mill. "Please understand," he said in a very deep, very profound silence, "that I haven't heard the full text, and that the bridge between the atevi and human languages is very difficult on some topics such as confidence or nonconfidence, for biological reasons. Even after my years of study I've discovered immense difference in what I thought versus what I now realize of atevi understanding. Words I've always been told are direct equivalents have turned out not to be equivalent at all. But that I do understand gives me hope, even if —" he laid a hand on the sling "– it was a painful acquisition – that if my brain can make the adjustment to your way of thinking, then there must be words; and if I can find the words I can deal with this. Believe me, tonight, that what I hear on that tape disturbs me, but does not alarm me. I hear no threat of war, rather typical posturing and position-taking, preface to negotiation, not to conflict."

"Have they, nadi, not mentioned atevi?" The question, coldly posed, came from the conservative Minister of Defense. "Am I mistaken that that word occurs?"

"Only insofar as, nandi, in the discussion of territory, Mospheira asserted its sovereignty over humans."

"Sovereignty," Judiciary repeated.

Loaded word. Very.

"Sovereignty over humans was the phrase, nand' Minister. Remember, please, the President can't use the atevi word 'association' to them and make the ship's captain understand it. He has to use words – as do I in translation – which carry inconvenient historical baggage. We don't have a perfect translation for every thought. This is why the paidhi exists, and I will be very sure the President understands his Treaty obligations and that he's sensitive to implications in translation. The Treaty will stand."

Suspicions remained evident, but tempers were settling, judgment at least deferred. The shoulder ached, muscle tension, perhaps, and he tried to relax – impossible thought, when he was beginning to shiver in the draft from the doorway.

"There is a rumor," Finance said, "that humans have built more ships."

"I believe I can deny that, nand' Minister, unless someone besides the paidhi understands that from some tape I haven't heard." He said it, and Hankslanded on his mind like a hammer blow. "I ask you, nadiin, please, when you hear such things, make me aware of them, so that I can address them as they deserve in information I give to you. I'll certainly listen to the tapes with that in mind, nandi, and I thank you for the information."

Finance gave a mollified bow of assent, her face entirely expressionless as she leaned back and regarded him under lowered brows.

Meanwhile the room was swinging around and around, and there was no good trying to request to leave until it stopped – the waves of dizziness when they started having at least a few minutes to run. "Be assured," he said, "that I'm back in business – a little weak today, but don't hesitate to send me queries and information at any hour. That's my job."

"The paidhi," Tabini interjected, "is staying in the Atigeini residence for security reasons. You may direct your phone calls and your messages there. Hanks is not here officially. We have cleared up that matter and are proceeding to clear it up with Mospheira."

Some little consternation and curiosity attended on that remark.

"What of the Treaty?" Judiciary asked. " Onehuman."

"They apparently thought I'd died," Bren said. "And since I'm alive, but injured, it's possible they left Hanks in place thinking I wasn't up to my duties. I left Mospheira very rapidly after surgery this morning, and it's possible they briefed me on a number of things immediately after I came to, but I fear I didn't retain them. I by no means dispute she's in violation, but it's likely only a confusion of signals in a very rapidly evolving situation. While I'm paidhi, I promise you, nadiin, ship or no ship, Mospheira will stay within the Treaty."

Triti, in the atevi language. Which they roughly defined as a human concept of association – as humans thought atevi association meant government or confederation, not feelingthe instinctual level of it. Bandy "treaty" about in the atevi language in most quarters with any suggestion of it as a paper document and one risked real confusion of human motives.

"But this 'sovereignty,' " Transportation objected.

"Is a difficult word," he said. "A rebel word to you, but it doesn't have such connotations in Mosphei'. It applies to their relations with each other, not with atevi, nand' Minister. How does it stand now? Has there been much more conversation?"

"Not between these two individuals," Defense said, dour-faced, and finding preoccupation in his pen and a paper clip. "We do have numerous exchanges between what we suspect to be lower-level authorities."

"Probably correct, nadi." He felt a sense of panic, sorting wildly through two languages, two psychological, historical realities, trying to make them seamless. "The fact that they've turned talk over to subordinates doesn't mean a settlement or a feud, merely that there's no agreement substantial enough to enable two leaders to talk."

"Two leaders, nadi." Defense was unwontedly peremptory, even rude in that "nadi," evidencing disturbance in his voice. "Two, is it?"

"It's not certain." He fought for calm. It wasn't terri tory he wanted to explore. "Not at all certain, nand' Minister. I think they're trying to see if association exists. I think historically they'll conclude it does. But if they can't find it, I can't imagine that one ship could think it outranks the entire population of Mospheira. At worst, or best, the ship might withdraw to elsewhere in the solar system. I just can't – can't – be definitive right now —"

"The paidhi," Tabini said, "is very tired, and in pain, nadiin. Thank him for his extraordinary effort on this matter, and let him go to his bed and rest tonight. Will you not, nand' paidhi?"

"Aiji-ma, if I had the strength I'd stay, but, yes, I – think that's wise. The shoulder's hurting – quite sharply."

"Then I'll turn you back to your escort and wish you good night, paidhi-ji. I ask you to consider your safety extremely important, and extremely threatened, perhaps even from human agencies. Stay to your security, night and day, nand' paidhi."

Why? was the question that leaped up, disturbing his composure in front of a table full of lords and representatives, some of whom might have been in consultation with Hanks. He wished Tabini hadn't added that – and tumbling to why, he thought: to let the troublemakers in the Association think about the hazard of making associations no ateva understood – like Hanks.

Clever of the man, Bren thought. One could admire Tabini's artistry at a distance. One just didn't want to be the subject of it – and he couldn't protest to the contrary, or call the aiji a liar. He certainly couldn't say that Hanks was an innocent in Tabini's difficulties.

One just, with the help of the table, struggled to his feet, bowed to the assembled committee chairmen – and lost the coat off his shoulders – another twinge as he tried to save it.

Banichi quietly intervened to save his dignity, adjusted the coat, and the lords and representatives gave him the courtesy of bows from their seats, two even rising in respect of his performance, when he was less than certain it was credible or creditable.

"See he rests," Tabini said to Banichi and Jago. "Straight to bed. No formalities, no excuses."

The paidhi had no argument at all with that instruction. He'd believed only giddy minutes ago that he'd controlled that conversation at least enough to hold his own.

But once out of Tabini's immediate presence the spell was broken, the excitement ebbed, and adrenaline was shifting from second-to-second performance to the raw fear that he had a human situation on his hands and that he'd given atevi far too much information.

It hadn't been a total mistake to agree to Tabini's requests. Sometimes he'd gotten extraordinary results when Tabini pulled one of his must-talks. Sometimes he'd been able to skate along on dangerously thin ice, maybe giving just a shade more to Tabini's demands for information than the Department would ever feel comfortable with —

But, dammit, getting concessions back, too – more cooperation between this aiji and Mospheira in his few years in Shejidan than his predecessor had gotten from Tabini's father in his whole career. He'd won expansions of the Treaty, he'd increased trade —

He hadn't said anything that, by the Treaty, they weren't entitled to have, or done anything that he hadn't promised to do when he got back to Shejidan, but he walked the lower hall from the meeting room under the escort of Banichi and Jago, in increasing distress over the tone and tenor of the meeting – definite deterioration in atevi confidence. Definite unease. And maybe justified unease. He needed to talk to Hanks – find out what she'd done and said, and what she understood as the truth.

Meanwhile Banichi talked to someone on his pocket-com, the device against his ear, and directed him to an express lift he was well familiar with, the one he'd used «n his other visits to the third floor. He rode it up with Banichi, seeing the conference room downstairs more vividly than the utilitarian metal around them – reviewing the nuance of remembered dialogue, and agonizing over how, without going back and forth with Mospheira, he was going to straighten out concepts.

More, there were names in the text, which made it a human Rosetta Stone for atevi grammarians. An extensive text limited to topics on which atevi already knew certain Mosphei' words – and knowing words didn't mean knowing the language. Words like loyalty that didn't quite mean man'chi;and propriety that didn't quite mean kabiu;and, on the atevi side, tritithat, unknown to most humans, didn't mean treaty, but a homing instinct under fire – damnHanks and her assumptions.

Her campaigning for atevi partisans of her own couldn't be Foreign Office policy. The faction behind Hanks had absolutely no interest in screwing up on that dangerous a level. Hankswanted the job; Hanks wanted what she'd trained for all her life, heunderstood that – and she was flattered to be making real headway with the likes of lord Geigi and the hard-to-handle fringes of the Association, real proof of her competency, the hell with the university liberals who couldn'tbe right about the associational fringe elements…

Damn, damn, and damn.

They exited into the upper hall, near the door, walked the hand-loomed carpet runner past extravagant porcelain bouquets in glass cases.

He ought to call Mospheira and brief someone – tonight, if he could get a call through – if he could keep his wits about him to make a report, no surety at all.

Worse, he wasn't sure, in view of Hanks' being left here, that he dared pick up a phone to make a call or even receive one. He'd started down a course of action he couldn't backtrack on – and he couldn't afford to have the upper echelons of the Department pull the rug out from under the Foreign Office or the paidhi with any wait-for-official-decision or a mandated consultation with Hanks.

The paidhi had damned sure better have authority in the field. Atevi certainly thought he did. The aiji of Shejidan wouldn't talk to anyone who didn't have authority to make a decision stick.

It was a situation you had to stand on both sides of: for the currently serving paidhi, it meant living up to your ears in real-time guesswork.

And yes, sometimes even that paragon of Departmental rectitude, his predecessor, Wilson-paidhi, hadn't consulted.

The hall was a haze of gold carpet patterns and pastel porcelain bouquets and he felt increasingly sick at his stomach. He wanted to be in his bed without fuss, unconscious.

He wanted to wake up in the morning with an arm that didn't hurt and with a clear-headed, logical insight into how he was going to keep everything humans and atevi had built together from blowing up in their faces.

He also wanted, pettishly, to have had more personal time at home, dammit, before they dropped him back into the boiling oil. He'd won his time off: he'd planned to sit for at least a day on his brother's white-railed porch watching the waves roll in and letting his mind go to the zero-state it longed to achieve —

Paidhiin had taken fast action before to keep an aiji of Shejidan in power. But they'd never – never – handed over the human fall-back positions in negotiating before the State Department ever got to the negotiations.

God – he thought suddenly, as that hit, asking himself what he'd done. Or what he'd actually said, or they'd implied. He suddenly couldn't remember. It was all coming apart in his mind, bleeding into confusion as they reached his door, as Jago keyed through the lock into state-of-the-art security systems which could, if forced, deal death on an intruder in ways that made a human unused to such conveniences feel very, very queasy.

Tano met them in the foyer. That was a welcome surprise. Tano might have been chasing them since the airport, but he hadn't actually seen Tano since Malguri, and in the surreal flux of events around him he was ever so glad to see the man in good health. Tano was security the same as Banichi and Jago were: deadly and grim and all of that. But Tano was on hisside, on Tabini's orders, more particularly on Banichi's, and Banichi ranked very, very high in the Guild of Assassins by all he could figure.

"Your luggage is safe, nand' paidhi," Tano said. "I've also set your computer in safekeeping."

"Thank you, nadi. I verymuch regret your difficulties. I hope to be a very quiet resident here and give you absolutely no adventures."

Tano took his coat. "One does hope so, nand' paidhi." Another, probably real, servant appeared a few steps ahead of the gracious nadi Saidin, captured the coat from Tano and whisked it away under Saidin's direction, one supposed for cleaning and pressing. "There are messages," Saidin said, indicating the reception table by the door, where filigree silver message cylinders in daunting abundance waited in a silver basket, along with one paper simply rolled and sealed.

"The paidhi is exhausted, nadi," Banichi objected, which was only sense. Bren knew he should let those messages alone, go to bed and sleep the uneasy sleep of the truly morally compromised, without knowing or imagining who would have sent him messages so urgently early in his return: every head of every committee he'd just talked to downstairs, he was certain; plus every atevi official who saw in his accession to this apartment, and his return to Shejidan, the new importance of the paidhiin.

And possibly ordinary citizens as far as Malguri had recently seen the paidhi on local television and seen the ship in their skies and just wanted to ask: Are we and our children safe in our towns?

Certain cylinders announced their nature at a cursory glance. And, dammit, he wasn't constitutionally capable of walking past that table without assuring himself there wasn't a life-and-death communication in the lot.

Or word from Mospheira.

"A moment, nadiin-ji. Just a moment," he said and, shaky with exhaustion, nipped out of the basket the ones in particular that had caught his eye – the plain, uncylindered one: that usually meant telegrams from Mospheira; men two more, one seal that he feared he recognized, and one he was damned well sure of. Other familiar seals he didn't need to question: the head of the Space Committee – who hadn't been at the meeting, and who would have urgent, businesslike and thoroughly reason able questions to ask the paidhi, such as: Is there still a space program, nand' paidhi? What do we do?

And, dead sure, What can we tell the Appropriations Committee?

One certainly understood that good gentleman's concern. He saw the seals of Transportation and Trade, too – logical that they had questions for the paidhi: he hoped he'd answered them adequately downstairs.

But that cylinder of real silver was indeed the seal he'd thought it was, a diamond-centered crest he'd seen not so long ago and, in view of Tabini's warning, expected.

Grandmother.

The aiji-dowager.

Ilisidi had brought him to Shejidan. Saved his neck. And risked it. Awkward with the cast, he cracked the seal with his thumbnail, slid out the little scroll and pulled it open.