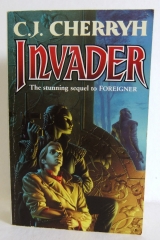

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

"Is that yourassessment of her thinking?"

"The paidhi is not a fool." Banichi had a half-amused look on his face. "Say I ask myself that question often in a day. Exactly. The affair between them – I doubt is sham. They've shown —" Banichi made a small motion of the fingers "– singularly foolish moments of attraction. That, I judge, is real; and staff in a better position than I to judge say the same. That doesn't mean they've taken leave of higher senses; Naidiri has standing orders that propriety is notto keep him out – while Damiri has relinquished her security staff, at least so far as her residence in the aiji's apartment: the necessary concession of the inferior partner in such an arrangement, and a very difficult position for her security to be in. Your presence – has been an incidental salve to Damiri's pride, and a test."

"In case I were murdered in my bed."

"It would be a very expensive gesture for the lady – who's made, by both gestures, a very strong statement of disaffection from the Atigeini policies. You should know that Tatiseigi has made a career of disagreement with Tabini and Tabini's father and his father with Tabini's grandfather, for that matter. And Damiri offers the possibility of formal alliance. Not only her most potent self as mother of an heir, but a chance to break the cabal in the Padi Valley – and possibly, withTatiseigi's knowledge… to double-cross the aiji. Or possibly to overthrow Tatiseigi's policies and his grasp of family authority."

"I take it this is not general knowledge."

"Common gossip. Not common knowledge, if the paidhi takes the difference in expressions."

"I do take it."

"This is a very dangerous time," Banichi said, "within the Association. Quite natural that stresses would tend to manifest. In Mospheiran affairs… likewise a time of change. As we understand." Banichi reached inside his jacket and pulled out a silver message cylinder. "Tabini asked us to brief you at least on the essentials of the neighbors. – And to destroy this andthe accompanying tape after you've read it."

Tabini's seal.

Damn, Bren thought, and took it with no little trepidation. He unrolled it, read, very simply put, after Tabini's heading,

Please observe great caution, do nothing to elude your security even for a moment. We expect a great deal of trouble, on very good advisement from very good sources.

The whereabouts of Hanks remains, specifically, a question. But we would not be surprised to find that she has been moved near Taiben, since the conspirators are few, their connections are strong in that vicinity, and they wish to bring as few as possible others of their fringes into public knowledge should matters go wrong for them. Certainly their more cautious supporters will not want to commit until and unless they demonstrate success.

I will not at all be surprised if individuals frequent in Hanks' association initiated the matter. She seems to be operating in some freedom. Banichi has a tape copy of a communication we intercepted on the mainland. Listen to it and see if you can make sense of it.

He expected, dammit, before Banichi gave him the tape and Jago got up and brought him a recorder to play it on, that the tape involved not ship-to-ground communications but very terrestrial connections indeed.

And that the front of the tape would be a great deal of computer chatter – as Deana's access code went through Mospheira's electronic barriers like a knife through butter.

Damn right her authorizations weren't pulled. Completely live. Completely credited, where they were going. He jacked in, captured-and-isolated, read-only, as scared of those codes near his computer as he would have been of a ticking bomb.

The text was, again foreseeably, scrambled. He tried three code sets with his computer before one clicked.

After that, text flowed on his screen.

Cameron has turned coat and threatened the ship with unspecified atevi hostilities in order to have them land under the aiji's control. He has meanwhile participated with the aiji's authority to place me under communications blackout and, I am warned by reliable sources, to have me assassinated. The motive is complex, resting in the aiji's ambitions to make the precedent of central control of dams, power grids, and rail apply to all natural resources, which will strip the provincial aijiin and the landholders of financial resources and centralize all international trade, with monopoly to the aiji in Shejidan, and consequently price controls which will considerably enrich the central government at the expense of local governments and rightful landholders.

Cameron has cooperated in this plan, whether wittingly or unwittingly, has actively backed the nationalization of resources, has suggested boycott as a tactic, has gone on a remarkable excursion to a remote observatory supported by the aiji of Shejidan and brought back a warped-space theory that I strongly believe is not based on atevi research, but on unauthorized translation of classified human mathematical concepts. This is calculated to disturb certain atevi conservative religious beliefs which are in stark contrast and political opposition to the aiji, who is not a believer in any philosophy, most particularly to throw certain provinces into religious upheaval and certain philosophical leaders into disrepute and disregard.

I am making this transmission from a secure base afforded me by the persons who have placed their lives in jeopardy by opposing this power grab on the part of the central government. In my judgment, we will do well to make this situation extremely clear to the representative from the ship if she in fact reaches Mospheira alive, which my informants suggest may not happen. The aiji may assassinate this individual and put the blame on his opposition. Since he clearly controls the Assassins' Guild, getting a filing against his political enemies at that point would be possible. This would also, I am informed, serve as a purge of the Guild, as all Guild members opposing his aims would very quickly find themselves targeted by the aiji's very extensive network.

I urge under the strongest terms that the government recall Cameron, revoke his authority and his codes, and demand an explanation of his actions, which are by no means in the interest of Mospheira, of the human population in general, or of atevi citizens. I do not know and cannot ascertain whether he is aware what he is aiding or to what purpose his advice and ability is being used, but I consider that my life is in present danger from agencies with whom he is working. Therefore I will move from place to place and attempt to preserve my usefulness in my job.

Please pass a message to my family that I am at the moment safe and well and protected by persons who have acted in behalf of their freedom and rights of self-determination.

He didn't swear. He didn't want expression to cross his face – he wasn't sure he was going to translate this message exactly, at this time, or in the foreseeable future. He rested his elbow on the armrest and his knuckle against his lip, thinking. He'd defined the beginning of the section; he defined the end; he captured, reran it, rereading to determine that, no, there was no hint of it being taken under duress, there were none of the words to signal that such was the case – and he'd hope, in a piece like that, to see words like discorrespondance, decorrelationary, or contrarecidivistic, that to a human eye didn't quite belong in typical text in the worst diplomatese – the standard freehand signal that the whole piece was under duress, always a worry when a note that explosive came in on computer-to-computer transmission.

But there was no such clue. He read it a third time simply to absorb the tenor and content, to try to strip out emotional reactions, and to ask himself honestly whether there was any remote, even astronomically remote or conceivable likelihood that Deana was actually right and he was wrong.

That Tabini's true aim in the current crisis was elimination of dissent.

No, dammit, it was notthe purpose of Tabini's actions. It was not the action of the aiji whose answer to rebels in Malguri had generally been understated, as witness Ilisidi's corroboration that things were settled; the aiji whose punitive use of the Guild had been, if at all during his administration, so covert as to be undetected. It was not the action of the aiji who, if reports were true, having perhaps assassinated his own father, at least declined to assassinate his grandmother, who was still in all accounts a very reasonable culprit in the demise of her son.

One added sideways and up and down and power grab didn't describe Tabini in the least.

It didn't describe Tabini's overenthusiastic (by Ilisidi's lights) embrace of things human; or his willingness, in personal argument with common citizens, constantly to push court suit and trial as an enlightened substitute for registered feud; his insistence to push air traffic control as the system countrywide in spite of lordly objections becauseit made sense, even if it sequenced five and six commoner pilots in line ahead of provincial aijiin and their precious purchased numbers in the landing sequence – it also kept aircraft from crashing into each other and raining destruction on urban Shejidan.

It didn't, as Banichi had pointed out, describe the aiji's support among the commons. Elected by the hasdrawad. It was a very enlightening view of whythe Western Association was stable. Human scholars called it economic interdependency, and believed the public good and public content propped Tabini's line in power – which might be the same information; but the economic changes Jago mentioned, bringing real economic power to the trades and the commons – yes, it was the same thing, but it was the atevi side of the looking-glass. And in the concept of man'chi, and atevi electorates – it was an atevi explanation for the peace lasting.

Because the hasdrawad wasn't about to vote against the interests of the commons. Which the hasdrawad hadn't seen as congruent with Ilisidi's passionate opposition to things the hasdrawad wanted, like more gadgets, more trade, more commerce, roads if they could push them, rail if that would move the freight, and to hell with the lords' game reserves: wildlife didn't rank with trains as long as wildlife, the only atevi meat supply, was in good supply in general. He'd heard the arguments in Transportation, in Commerce, in Trade… always the push for the big programs. Which no lord wanted if it wasn't in hisdistrict or his interest – or, contrarily, if it infringed his public lands, meaning the estate he used, and on which he hunted, during his seasons of residency.

He was aware of Banichi and Jago sitting opposite him, across the small service table. He was aware of them watching his face for reactions – and he shot Banichi a sudden, invasive stare.

"You can'thave broken the code in this document," he said to Banichi.

Banichi's face was completely guarded, not completely expressionless. A brow lifted, and the appraising stare came back at him.

One didn't pursue the likes of Banichi through thickets of guesswork and try to pin him down. Banichi wouldn't cooperate with such petty games.

One went, instead, straight ahead.

"You know this is from Hanks to Mospheira. And you know who she's with and what they'll have told her."

"One can certainly make a fair surmise."

"Hence what you just told me. About the election. About the hasdrawad."

"Bren-paidhi, what Tabini-aiji asked us to tell you. Yes."

"Meaning a handful of lords want to restore theirrights at the expense of the commons."

"One could hold that, yes. And, yes, if that is Hanks reporting to Mospheira, and the persons who have her have let her do this, andshe's done it willingly, one does rather well believe that she's at least convinced them she believes them. I take it the report she's made supports their view."

"You take it correctly. She has the opportunity, I'll be frank, to use words that would negate everything she says even if they did have a translator standing over her shoulder. There's no linguistic evidence an atevi dictated it word by word, and I'm not pleased with the content."

"I should have shot this woman," Jago muttered, "on the subway platform. I would have saved the aiji and the Association a great deal of bother."

"I've a question," Bren said, and with their attention: "Ilisidi – has always – to me – supported preservation of the environment, preservation of the culture. Not preservation of privilege."

"But," Jago said, "one must bea lord to assure the preservation of the fortresses, the land holdings, the reserves. A lord on his own can knock down ancient fortifications, rip up forest – it belongs to him. No association of mere citizens can stop him. And, no decree of the hasdrawad can dispossess the lords. The tashrid can veto, with a sufficient majority."

The airport at Wigairiin, he thought. The fourteenth-century fortifications. Knocked down for a runway.

For a lord's private plane. The lord's ancestors built the fortress. The lord inheriting it knocked the wall down, the tourists and posterity be damned.

"Do brickmasons and clericals on holiday… ever tour Wigairiin?" he asked – clearly perplexing Banichi and Jago.

"One doesn't think so," Jago said. "But I could find out this information, if there's some urgency to it."

"Nothing so urgent. One just notes – that such ordinary people do tour Malguri. With the dowager in residence. Whose doing is that?"

"Ultimately," Banichi said, "Tabini's."

"But Ilisidi has made no move to prevent it."

"Hardly prudent," Jago said.

"Nevertheless," he said.

"If some human reason prompts you to justify the dowager," Banichi said, "I would urge you, paidhi-ji, to accept atevi reasons to reserve judgment."

Things were at a bad pass when his atevi security had to remind him where things atevi began and things human ended.

"One respects the advice," he said. "Thank you. Thank you both – for your protection. For your good sense, in the face of my… occasional lapses in judgment – and security."

"Please," Jago said, "stay within our guard at Taiben. Take no chances."

He looked straight at Jago, and imagined, the way he'd imagined Jago avoiding him for the number of hours, that she intended the meeting of the eyes, that she looked at him in a very direct, very intimate way. Which made him flinch and duck.

"Considering all this," he said, trying to recover his train of thought, "in atevi ways the paidhi may be too foreign to reckon – howdid Ilisidi know about Barb the morning after I'd gotten the news? How do you think she knew that fast, if not directly from Damiri's staff? And why should Damiri and Ilisidi associate?"

There was a sober look on both opposing faces.

"Tabini has asked himself that very serious question," Banichi said. "And one does recall where Ilisidi is guesting today."

"Has he asked Damiri about it?" a human couldn't refrain from asking.

"Far too direct," Jago said. "We do lie, nadi-ji. Some of us do it very well. Certain of us even take public offense."

"Do youbelieve Damiri to be honest?"

"One can believe that Damiri-daja is quite honest," Banichi said, "and still know that she might be closer to her uncle's wishes than Tabini would wish. That is honest, paidhi-ji."

The only thing showing under the wings at Taiben was the endless prospect of trees, and at the very last the rail that ran between the airport and the township at Taiben, and the estate of Taiben, at opposite ends of the small rail line, two spurs.

And one was aware, watching that perspective unfold, that other short lines ran up to various townships, villages, hunting lodges and ancestral estates – including those of the Atigeini, and the other three lords of the valley.

The paidhi did have the rash and foolish thought that if, after collecting their luggage, they asked for a train not to Taiben but up to the Atigeini holding, in the north of the valley, they might actually have a civilized reception, a fair luncheon with Ilisidi, an exchange of civilized greetings, and a train ride back again to meet Tabini for supper at Taiben.

That was the way things went when lords met.

When the Guild met – other things resulted, and he wouldn't throw Banichi and Jago up against Cenedi and others of Ilisidi's household, not for any urging and not for any cause that he could prevent. Not that he lacked confidence Banichi and Jago would deal with the situation. And Cenedi. Who would be equally determined, at Ilisidi's order, though they'd fought together, cooperated, shared all the struggle at Malguri. In some ways, he suspected, humans who thought they had a monopoly on sensitivity couldn't imagine the feelings atevi had when some damned fool or some lord's ambition threw them into a conflict they didn't want and weren't going to win – in any personal sense.

So he was quite glad notto find any delegation from Cenedi waiting for them once they were on the ground; he was exceedingly glad that a quick security mate-up with personnel Tabini had had the foresight to send in last night in the dark had already ascertained that there was no bomb, no ambush and no accidental derailment to worry about on their route to Taiben. Everyone worried, at least aloud, about the paidhi's physical comfort, and asked how the flight had been, and the paidhi smiled and said it had been very pleasant.

More pleasant than security, who'd had to dislodge Ilisidi from the premises last night, damned sure; security who'd gotten no sleep whatsoever last night and, looking a little less crisp than the wont of Tabini's personal guard, undoubtedly hoped that they could get some rest very soon, now. So he asked no questions whatsoever of his own and boarded the rail for a rattling, slightly antiquated train ride to the south.

It took a winding long time getting there – no one who came to Taiben was supposed to be in a hurry —

Thinking about the lander, and the drop out of space; and the fact that the trip to push the lander into the atmosphere was actually underway by now, if he remotely understood the distance the station sat from the world, or the speed of the craft shoving the lander into final descent.

Thinking about Deana Hanks, and his having listened to her explanations, and halfway believing her – that was what made him angry: he'd askedfor her help, given her the looseness in contacting atevi sources which she'd probably used to get two good men killed —

He was mad, he was damned mad. And feeling betrayed, in a very personal sense, in his own judgment of another human being – he'd have thought instinct was worth something; and he'd argued with Banichi that she'd been upset at the attack, she'd tried to warn her guards —

One of them was a fool. Again. He'd fallen for her line about searching for him because it was noble, because it was what he'd have done – the search for him was herdamn excuse for contacting what Tabini called unacceptable persons, for going outside the lines; God, she'd had a field day in the atevi opposition, and not a theoretical opposition. She'd dropped FTL into the mix, all right, and maybe that had been a mistake, but she'd also damned near fractured a province and damned near taken out Geigi's influence – Geigi was one of the most scientifically literate lords in the tashrid andin the scientific committees. Geigi had fallen into her arguments, and so had he – refused to maintain his intellectual conviction that she could possibly be the ideologue he'd thought and still do a credible job – he'd held out in the contact they'd had, because at the back of his mind had been the fear of being alone, the need for somebody human to check with, to haveher contrary but human train of thought to consider. He'd needed her.

But right now, if something happened in the landing and the ship concluded atevi weren't civilized enough to deal with directly, that would suit her and her friends on Mospheira andher friends in the tashrid. They wanted something to go wrong. The radicals of both nations had found common cause. And he'd seen it possible – but he'd not seen it coming from the angle it had. He'd counted on Deana slowly gaining an understanding of atevi – God, how did you work that closely with them and still maintain humans had to have absolute dominance?

And how did atevi lords not see what she espoused – if not that it was so damned uniquely human?

He thought about aijiin, and antiquity, and how, yes, humans had studied the Padi Valley origins of the Western Association, but in the way of humans not hardwired for such understandings, humans hadn't known instinctively, as would have been obvious to atevi, that that formerly powerful association would never turn the participants loose, not so long as they retained any territorial holdings here, not so long as they remotely had interests here – The hierarchies would still operate and the rivalries would still exist.

(Mecheiti on the hillside, shoving each other dangerously for position, because there was just one mecheit'aiji, one leader, and there was a rival, and there were almost-rivals – and those far enough down the order of things they didn't contend.)

Humans concentrated on the competitions of economics and never saw the opposition of the tashrid to Tabini as significant. They saw atevi adopting a human pattern, democratization following a rise in the middle class.

Wrong.

Very damn wrong. Democratization had happened beforethe economic rise of the middle class, democratization in order to secure the rise of a middle class, maybe because the first paidhi, in his need to communicate about human decision process, had let slip something to his aiji as disturbing in its day as FTL to Geigi's philosophy.

There wasn't such a thing as a solitary creature in all the world. The wi'itkitiin perhaps came closest. But even they nested in associations. If there was one – there'd be others. Crawling their way uphill from their brief flights, doggedly, determined in their courses, they got back to their cliffs, those that survived the predators. Damned stubborn. As atevi were. As mecheiti were. They didn't give up on a project. They didn't give up on an effort. Lords didn't give up. It could go thousands of years; they didn't give up, the way, perhaps, wi'itikiin didn't give up their ancestral nests on ancestral relative heights on ancestral cliffs. Atevi wrote downtheir purposes, and told them to their children, so they never damned well forgot.

Very bad enemies, he thought, watching the valley unwind in front of them, watching the distant brown tile roofs of Taiben appear in the distance above the trees.

Humans who didn't know that, didn't know the atevi. Not their good points nor their bad. Deana didn't know what she'd tied into. Deana was still operating – he was willing, in the face of all other misjudgments he'd made, to bet on this one as truth – on the theory that what one saw in atevi now had always been true; that the opposition to Tabini was a political and not a biological impulse; that economics drove atevi to the same extent and in the same way as it drove Mospheiran humans.

Naturally. It was her specialty. What was her paper? Economic determinism?

It wasn't his field, but he knew the premise: that industrial society ultimately produced like social institutions.

No need for Deana to struggle with nuances of the language – atevi would grow more and more like humans. She'd just deal with the atevi that agreed with her position. Her friends in the Heritage Party didn't want to understand atevi – just deal with them. Just the way it was when Wilson was in office.

Right, Deana. No arguing with success.

CHAPTER 21

The servants were waiting on the rustic back porch of the lodge as the train pulled in to the platform. They insisted on snatching his bags and they chattered at him about the accommodations.

And perhaps it was the sight of familiar ground, where, at every visit, only pleasant things had happened; perhaps it was, despite the crowd of female servants, the comfortable recognition of an odd stone in the porch wall, the sight of its unshaped wood, its muted browns and stone grays, the plain character of its timber-and-stone halls – he felt as if he'd shed the Bu-javid at the door, as if, here, the landing itself was finally real, and he could actually do something about the problems it brought with it. He walked from the train depot door, down the hall with its hunting memorabilia and the leather couches and wooden benches, let his baggage find its way to the other wing while he lingered in the formal reception hall with the benches and the fireplace. To his pleasure, the servants or, more likely, Gaimi and Seraso, chief of the permanent, year-round ranger staff, who used Taiben when the family wasn't in residence, had a small fire going to welcome him, mostly of aromatics, the sort of thing the rangers laid by after clearing brush. The room smelled of evergreen and oilwood.

Beyond that was his room. Hisroom, when he stayed at Taiben, a very comfortable room, with country quilts as well as the furs, a bedstead that could have stood in an earthquake, a trio of tables, and a wood-carving of a stand of seven trees that wasn't grand art or anything, but elegantly executed and pleasant.

His bed. A mattress he knew. A bathroom with a propane heater for winter. Shower tiles with wildflowers hand-painted on them. He realized he'd drawn a deep, deep breath, and that something in his chest had unknotted the minute he'd stepped off the train.

Then Tabini's security staff arrived to say they had chosen two rooms next to his for the foreigner paidhiin, if he would care to inspect them, and his mind snapped back to the business of descending landers, terrified spacefarers probably enroute at the very moment.

He viewed the rooms, one after the other; rooms like his own, one with a sling chair made of marvelously shaped driftwood and red leather, one with a human-high carved screen showing a hunting party, and asked himself what they'd think, surrounded by stone and wood and live flame, which was, he was sure, very unlike the station or the ship. But he assured Naidiri's two assistants and the servants that they were magnificent rooms fully proper for foreigner paidhiin – they didn't, he was thinking to himself, have trophy heads on the walls, which was probably just as well.

A senior servant came in with a bouquet of wildflowers of, she assured him, felicitous color and number, and said that such rooms and such a place would surely help assure harmony, as the servant said, "The numbers of the earth run through this house. They can't be infelicitous with the numbers of the heavens."

"One certainly agrees, nadi," he murmured, finding a comfort in the reckoning that wasn't humanly rational – just that atevi thought it worked, atevi arranged things with good will in mind, very simply conceived good will that said they should all be harmonious and fortunate. "I think it's very well done. Very well thought, nadiin. They should feel well taken care of."

He couldrelax, then, at least enough to leave the servants to install his small amount of clothing in the drawers and the closet and to press what wanted pressing. He went outside to stand on the porch and breathe the free air, looking out over the hillside.

Taiben sat on a gentle slope, its rearmost sections camouflaged in the edge of a hillside forest, its porch shaded by trees. In this season, in the nightly chill of the hills, grasses were just turning from green to gold: a hundred meters on, trees and brush began to give way to meadow-lands which ran on and on, interspersed with trees, to what they called the south range – and the landing site, a good drive distant.

He'd hiked a lot of the grassland. And the south range. Tabini had dragged him here and there around the reserve – an easy matter for Tabini, whose long legs never felt the strain. Which wasn't fair – in a man who spent his life in the Bu-javid and came out here to wear the paidhi to a state of exhaustion.

A lot of dusty hiking about, and firing guns, which the paidhi wasn't supposed to do, and which, not so long ago, the paidhi would have been just as glad to skip in favor of sitting about the fire all day and resting – when he'd come here, he'd usually been on the end of a long, long work schedule. He was now.

But if he'd the choice, he'd like to leave the porch and take a long walk off into the meadow. Which would be about the stupidest thing the paidhi could think of. When atevi security said, Stay in sight, they meant, Stay in sight. They were understandably short-fused, and being very efficient, very polite. He'd no desire to make their job harder.

So he trudged back inside, called for a pot of tea and watched – rare sight – the play of flames in the fireplace for the better part of an hour while servants hurried about their business and security crawled about in places atevi didn't fit, installing security devices, some of which might be lethal: he didn't ask.

Banichi came back with traces of dust and gravel on his knees and said he'd appreciate a pot of tea himself. Which meant, he was sure, Banichi had overtaxed his recent injury and was feeling it.

"Game of darts?" Banichi said when he'd had a chance to catch his breath and sip half a cup of tea. It was one human game atevi had taken to with a passion approaching that for television. He suspected he was going to lose.

Worse, as happened. Banichi offered him a handicap. He refused to take it. Banichi shrugged and still backed up a couple of meters —"Longer arm," Banichi said. "Let's be fair."

It was a slaughter, all the same. Four rounds of it.

"I don't think you canmiss," Bren said.

Banichi laughed, and put one in the margin. "There. What do you say? No one's perfect?"

Bren made his best try to put one dead center. Which got him a finger's breadth out. "Well," he said, "some of us miss better than others."