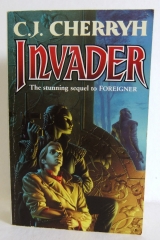

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

His message-load held personal letters from a list of correspondents he'd flagged as always full-text, at least as full-text as the censors let him have, ranging from university professors of linguistics and semantics, to old neighborhood friends giving him news of spouses, kids and summer vacations.

And came the State Department output, which was not, this time, highly informative: information on pensions. Helpful. God.

Some of it had to go – he ordered Explore, and saw the Interactives come back with characteristics and content of the files; he asked it next to Search ship/Phoenix/station/history content, and it came back with lists.

And lists.

And lists.

With tags of correspondents both regular and names he didn't at all know: everyone with access to the Foreign Office had had an opinion and offered it when the news broke about the ship returning, that was what had happened – he'd done such a fast turnaround the staff hadn't had the time they usually had to weed and condense – meaning he had the whole damned load, God help him, every crackpot who could find the address in the phonefile.

Several of the files were absolutely huge. University papers. Theses. Dissertations.

He hadn't thought it possible to crowd the memory limits. It was a bigstorage. He checked through the overlays, scared something might have started a memory resident to chewing up the available space, but nothing checked out as active but things that ought to be, and nothing was actively eating memory. It was just that much data he'd sucked up in his connection time.

It wasn't going to be an easy sift-out. The computer was going to have to search and search.

And there was one thing he had to do, before he sank all the way into study: he asked Saidin for a phone, sat down in his bathrobe and, calmly composed, called through the Bu-javid phone system with a request for Hanks-paidhi.

Not available, the operator said.

"Message to her residence," he said patiently, very patiently.

"Proceed, nand' paidhi. Record now."

"Hanks-paidhi," he said in the atevi language. "Kindly return my call. We have urgent business. End, thank you, nadi."

The bloody hellHanks wasn't available. He took a deep breath, dismissed Hanks and her maneuvers from his list of critical matters, and went back to his chair and his computer.

He set his background search criteria, then, to his needs, defaulted to print-matches-to-screen at his own high-rate data-speed, which was damn fast when he was motivated and the criteria were subject-narrow: a lifetime of foreign language, semantics, dictionary work and theoretical linguistics gave him some advantages in mental processing and rapid reading, and what he did in his head with the files was a personal Search and Dump and Store that didn't even half rely on conscious brain. Just the relevant stuff reached the mental data banks, a process that rapidly occupied all the circuits, preempted the pain receptors, turned off everything but the eyes and the fingers on a very limited set of buttons.

What came through to him was an impression, variously derived from his university scholar correspondents and the mishmash from correspondents both authorized and not, of a degree of concern about the ship's long absence, and its careful questioning of Mospheiran officials.

He couldn't nail the specific questions: the letter that might have been most specific was full of censored holes.

But references abounded to that bitter dispute among the original settlers, whether to land on the one livable world in the system, or mine and stay in space. There were specific names of ship crew, which he tagged as useful – who had been in important positions versus where descendants ranked might tell him something about the difference between the power structures that existed two hundred years ago – the foundation of scholarly and governmental assumptions – and those that existed now: clues to the passing of power downward.

A university professor he'd thought long-retired offered him information about the final ship-station exchanges, a file which contained exact quotes. Those he dived after and read, and read, and read, at a speed at which his eyes dried out and his teacup stayed suspended until a deft touch removed it from his hand.

Banichi said, "Would the paidhi care for hot tea?"

"Thank you," he said, stopped the dataflow of that not-friendly exchange, and took a brief intermission to what atevi genteelly called the necessity.

A servant had meanwhile supplied a fresh teapot, a clean cup and a plate of wafers, and he restarted the dataflow three minutes before the interrupt point.

The sun inched up out of the window. Lunch appeared, sandwiches ceremoniously brought to his chair. .

There arrived, with it, Banichi, and a message from Tabini that asked whether he had any questions Banichi and Jago couldn't answer. "No, nadi," he said to Banichi's inquiry. "Just the ground-station transmission records. Please. Do you have any idea the reason of the delay, nadi?"

"I believe they're changing format," Banichi said.

"Banichi, if I'm supposed to listen to the tapes, I don't need the intelligence people to clean them up. Peel the access codes out, I don't careabout the numbers, I swear to you, I don't have to have their precious numbers – we're not 'counters here. Just get me the damn – excuse me – voice recordings. That's all I ask, nadi."

"I'll urge this point with Tabini. I need the paidhi's authority to approach him against other orders."

"Please do." He was frustrated. Time was running. Someone in Defense was apparently holding things up for real concerns or obstructionist motives. He couldn't guess. He couldn't let go of his thoughts. He'd built too fragile a web of translated conjecture. He'd never yet taken his eyes from his screen and the reminders of where he was in the structure; and when Banichi left, he reached for half a sandwich with the same attention he'd given his teacup, then dived back into his work, only moving a leg that had gone to sleep.

"Tabini-aiji asks," Banichi said at another necessity-break, "if the paidhi would care to issue a statement for the news. It's by no means a command. Only a suggestion, if the paidhi is able."

> "Tell them," he said, floundering brain-overloaded in a sea of input, "tell them in my name that I would wish to speak to them, but I'm in the middle of a briefing. Whatever you can contrive, Banichi-ji. I can't possibly issue a definitive statement yet. I'm translating and memorizing as fast as I can. I'm drowning in details. – And they won't get me the records. What in hell are they doing, Banichi?"

"One is aware," Banichi said carefully. "Steps have been taken. Forgive my intrusion."

Banichi was a professional – at the various things Banichi did. The paidhi at the moment had one focus: data and cross-connection; reading for hourson end at unremitting scroll.

Figuring out how, with a limited dictionary, to explain interstellar flight in unambiguous words for the Determinists and the Rational Absolutists, whose universe didn't admit faster-than-light, was absolutely terrifying. Hedidn't understand FTL, himself, and finding two atevi-mentality numerical philosophies a linguistic straw of paradox to cling to, to keep two provinces of the Association from disintegrating into riot, made his brain ache. It was all a structure of contrived cross-connections and special pigeonholes for the linguistically, historically, mathematically and physically irresolvable – and he hoped to God nobody asked the question.

Especially when all the historical information contradicted itself – and indicated the Mospheiran records, God help him, were not infallible.

Paidhiin before him had elevated atevi science from the steam engine to television, fast food, scheduled airlines, and a space program – and he didn't know if the next step might be Armageddon.

So he bent himself again to his reading, seeing the Seeker had come up with a further digest of content – slow, memory-hungry operation, running slower than usual in the background – and had the summary of thirty-three trivial files, all inquiries, none informative.

That could go down to temp-store on a card. Free up memory. Make the computer run faster. The paidhi had other problems.

And, seeing that the Seeker had created another ship/ history thread through a chain of files, he said, "Thread, ship/history, collect," and saw the result rip past at his fast-study speed.

But the information wouldn't coalesce for him. He'd blown his concentration or there was something else knocking at the back door of his awareness, something large and far-reaching, all associative circuits occupied —

"Forgive me again," Banichi said, and Bren restrained a frantic impulse to wave it off, because he had almost realized there was something there.

But Banichi laid a recorder on the table – along with a message cylinder carrying the red-and-black seal that indicated it came from Tabini himself.

Thoughts went to the winds. He suffered a cold chill, murmured a, "Thank you, nadi, wait a moment," and opened the message cylinder, finding a note in Tabini's hand: This is the complete record, paidhi-ji, with the numbers. I hope this proves helpful.

He hoped to God. He found lunch not sitting well on his stomach. "Thank you, nadi-ji," he said, dismissing Banichi to his own business, and lost no time first in setting his computer to run full bore on the time-consuming Seeker summary program, then in setting the recorder to play back.

The first of it – he'd heard last night. He sped past that and fast-played the computer chatter.

More voices, then.

It fit the suspicion he'd formed from the records he'd been handed – the parting nastiness of Pilots' Guild politics suddenly played out real-time in what had gone on while he was in the east: the Pilots' Guild, for reasons for which one had to trust the distinguished university professor's unpublished history, had cast some obstacles in the way of the Landing all those years ago, ostensibly to protect atevi civilization.

But, the professor's account suggested, the Guild had both promoted and double-crossed the operation, because the Guild's real objective had been to maintain the ship as paramount, over the station, over any planetary settlement. The Guild had intended to run human affairs – as it had done during the long struggle to get to the earth of the atevi.

Trusting any history for the truth in a situation rapidly becoming current was, by its very nature, trusting a sifted, condensed account of hour-by-hour centuries-old events that he couldn't recover – events sifted by somebody with a point of view rooted in his own time, his own points to prove. He doubted that the detail he needed still existed even in the computer records on Mospheira: the war had taken out one big mass of files.

The fact was – he knew far less about Phoenixthan he knew about atevi; he knew Phoenix'present attitudes, inclinations and crew list less than he knew the geography of the moon. He didn't knowwhat Phoenixmeant, or intended, or threatened.

He didn't know the capabilities of the ship, whether it had traveled at FTL speeds or – considering the length of time it had been gone – sublight, which seemed a possibility.

But, ominously, the dialogue between ship and ground-station had gone from massively informative and high-level in the initial moments to, finally, the converse of under-secretaries and ship's officers niggling their way through questions neither side was willing to bring anybody to the microphone to answer.

What was the state of affairs, the ship asked, between Mospheira and the world's native population?

Mospheira wasn't answering that question. The State Department, the same close-mouthed upper echelon that backed Deana Hanks, was advising the President on an entity it didn't know a damned thing about; and the executive once it got involved was used to having weeks, months, even years and decades to study and debate a problem.

Mospheira didn't haveor wantrapid change. The social and technological dynamics meant what was, would be, foreseeably, for fifty, a hundred years, and its planning was always well in advance, a simple steerage of the world at large, atevi and human, toward matching technological bases, toward goals decades away. And if the executive got off its butt and moved – the sub-offices through which governmental communications ran weren't geared to decide faster than they did.

And if the ship knew what it wanted and pushed…

He listened, as back the two sides came to another foot-dragging exchange of minor ship officers demanding station records which they thought Mospheira should have; and after a day and a half, by the time markers, another exchange demanding in turn where the ship had been for two hundred years.

Damn again, Bren thought, hearing Phoenixignore the question and then hail the world at large, wondering if anyone else down there was listening.

Phoenixwas trying to make contact on its own. Thank God nobody in the atevi world understood enough to fire back an answer and begin a dialogue. Thank God the Treaty provided the paidhi at least as a unified contact point. Phoenixwas unknowingly charting a very dangerous course.

After that the ship broke off transmissions for what seemed a long time, and atevi date notations on the tape confirmed it. The ship asked no questions and ominously provided not one answer, not one clue to the President's persistent questions: Where have you been? Why have you come back? What do you want here now?

Mospheira had revealed a great deal to the incomers – necessarily, with the whole planet spread out for the orbiting ship to see – a tapestry of railroads and lighted towns and cities and airports, the same on one side of the strait as on the other, which had not at all been the case when the ship left. And he knew what the ship's optics were capable of seeing, at least the equal of what Mospheira had been able to see through the failing eyes of the station – hype that several times, for what a ship with undamaged optics could pick up.

And there was no way to see inside the ship or the station.

While Mospheira had, he mused, knuckle pressed against his lips, revealed more in its questions than it might realize, too, certainly to him. He knew the Department, he knew the executive, he knew personalities – the ship didn't, unless it discovered old patterns, but, damn, he could almost detect the fingerprints on the questions, the responses, the attitudes. It was Jules Erton, senior Policy; it was Claudia Swynton – it was the President's Chief of Staff, George Barrulin: the President didn't haveopinions until George told him what he thought.

The records became contemporaneous. Mospheira talked. The ship continued its efforts at contacting population centers, Shejidan in particular. There hadn't been contact between the ship and Mospheira for two days. The ship was notcurrently answering questions from Mospheira about its business or its activities.

The cold that had started with his arm had spread to a general shivery unease and left him wishing – which he never thought in his life he would wish – that he could pick up the phone, call Deana Hanks, and say, amicably, sanely, Look, Deana, differences aside – we have a problem.

Which was not, damn the woman, a comfortable proposition. The rift was not a resolvable rift between two people, it was ideological, between two political philosophies on Mospheira. The camp he feared now had thrown Deana Hanks onto the mainland was the same that had supported Hanks through the selection process no matter her test scores, and he suspected foreknowledge of key questions she stillhadn't answered with as high a score as his, as well as outside help on the requisite paper. She was Raymond Gaylord Hanks' granddaughter, and S. Gaylord Hanks' daughter: that was old, old politics, a conservative element that had, ever since the war, argued that Shejidan was secretly hostile – the same damned suspicion among humans that, mirror-image among atevi, believed in death rays on the station, maintained that the atevi space program got atevi funding because, along with getting into space, atevi meant to take the station and use it as a base to deny access for Mospheira.

The fixation of the conservatives lately was the snowballing advances in technology during his and Wilson's tenure, both technological and social: the conservatives held that Tabini was hostile and using a naive paidhi for his own purposes.

That very conservative camp of human interests moldered away, not in obscure university posts, but in the halls of the presidency, the legislature: they were the old guard politicians, whose families had been in politics since the war, in an island community where politics had traditionally not mattered a damn in ordinary human affairs and nepotism got more immediate results.

In the State Department, most of the view-with-alarmers were at senior levels, entrenched in lifelong tenancies: they had never, ever accepted the official atevi assertion that Tabini was innocent of his father's assassination. It was a tenet of the conservative faith that Tabini had done it, and that Tabini had demanded Wilson-paidhi resign to get a new and naive paidhi to carry out his programs.

In brutal atevi fact, they were very probably right, granted Tabini's grandmother hadn't beaten him to it – but parricide didn't weigh the same on the mainland as it did on Mospheira. One just couldn't judge atevi by human ethics. Assassinate someone of the same man'chi, the same hierarchical loyalty? That was shocking.

Assassinate a relative? That was possibly a rational solution.

The damn trouble was – the paidhi had far better pipelines and mechanisms for dispensing new information into the atevi mainland than he had for moving public opinion on Mospheira. It had never been necessarybefore for the paidhi to convince Mospheirans. It had never been necessarybefore for the paidhi to campaign against the conservatives, because the conservatives had never had a crisis in which they could move members of academe, as he feared they had done, to interfere in the paidhi's office.

But the academic insulation that supported the paidhi and assisted in the decision-making – usually without the politicians involved in the process – was a politically naive group of people, who, confronted with panic, might have been rushed to put Hanks in a position where she could at least observe at a time when lack of information seemed very ominous.

He'd never taken Hanks seriously. He'd taken for granted that she'd drown quietly in academe and be so old if she ever got the appointment she'd likely decline it, immersed lifelong in Mospheiran ways and incapable of adjusting if she got here. He'd trusted the academics to just keep shunting his conservative albatross aside for decades, give her some tenured professorship in Philosophy of Contact or some other nap class. Ask him a year ago and he'd have said that was the future of Deana Hanks.

It wasn't.

The shiver that had started wouldn't go away. It wasn't fear, he said to himself. It was simply sitting in one spot in what he now realized, by the blowing of the curtains, was a draft from the windows, until his legs went to sleep. It was the aftereffects of anesthetic. It was the whole crisis he'd been through —

It was the whole, damnable, mishandled situation. He'd been in the eastern part of the continent, out of the information loop, when atevi needed him most. It might not be his fault; atevi might have put him there temporarily until they were assured they could rely on – not trust – him.

But for whatever necessary satisfaction of atevi suspicion, he had been kept in the dark, all the same, and now if he misstepped – if he was even apprehended to misstep, politically – or if he pulled a mistake like Hanks' mistake with lord Geigi, which he stillhad to clean up —

Hell. He'd made a few mistakes himself, early on in his tenure.

And hell twice – the woman had to have some sense, somewhere located. You couldn't get through Comparative Reasoning or the math and physics requirements if you hadn't at least the ability to draw abstract conclusions. He should give reason a try.

He extricated himself from the chair, bit by slow bit and, letting his foot tingle back to awareness, got up and pulled the bell-cord. Saidin answered it. He sent Saidin after Jago, and Jago to deliver two verbal messages. To Tabini: I've learned all I'm likely to find out. I'm ready to talk to the public.

And to Deana Hanks: I will shortly issue an official position on the ship presence; you will receive a copy. We need to talk. Is tomorrow evening possibly agreeable to your schedule?

Then he went back to his chair, tucked up, and shut his eyes. Amazing how fast, how heavily sleep could come down, once the decision was made and the load was off.

But he could afford to sleep now, he said to himself. Other people could deal with the scheduling and the meetings and the arranging of things. He half-waked when someone settled a coverlet over his legs, decided they didn't need him, that the ship hadn't swooped down with death rays yet, and he simply hugged the coverlet up over a breeze-chilled arm and enjoyed the comfortable angle he'd found.

He waked again when Jago came to him, called his name and gave him another message cylinder sealed with Tabini's seal.

It gave the time of the joint session as midevening, unusual for atevi legislative proceedings, and added, simply, Your attendance and interpretations are gratefully requested, nand' paidhi.

"Any other message?" he asked. "Anything from the island?"

"No, I regret not, Bren-ji."

"Did you talk to Deana Hanks? What did she say?"

"She was very courteous," Jago said. "She listened. She said tell you a word. I hesitate to say it."

"In Mosphei', she gave you this word."

"I think that go-to-'elleis rude. Do I apprehend correctly?"

Temper – was not what would serve him this evening. He made his face quite impassive.

"I made no answer," Jago said. "I am embarrassed to bring you such a report. If you have an answer, I will certainly carry it. Or we can bring this person to your office, Bren-paidhi."

Tempting. "Jago-ji, I've sent you to a fool. You will get an apology, or satisfaction."

"There are less comfortable accommodations than your old apartment, Bren-ji."

"She's in myapartment?"

Jago shrugged. "I fear so, Bren-ji. If I were handling her security, I'd advise otherwise."

"I want her moved out. Speak to Housing. This is not a woman without enemies."

Jago made a little moue, seemed to be thinking, and finally said, "Her security is very tight – for such a sieve. In terms of live bodies, quite a high level. I speak in confidence."

"I've no doubt. Tabini'ssecurity?"

"Yes. Which the aiji can relax at will."

Meaning leave her completely unprotected. Jago didn't breach Tabini's security on a whim. That Jago told him anything at all on a matter she didn't need to mention was troubling.

"Did Tabini tell you to tell me this?"

Jago's face was at its most unreadable.

"No," she said.

Which meant narrowly what you could get it to mean – but when Jago took that tone, there was no more information forthcoming.

CHAPTER 6

Plastic bags, scavenged from the post office downstairs, the female servants declared in triumph; and tape from the same source. It was Tano's idea, so that a disreputable-feeling human, pushed beyond an already-fading interspecies modesty, could enjoy a real, honest-to-God hot shower, with all the bandages and the cast protected: "Nand' paidhi, you don't want to get water under the cast," was Tano's judgment. "Trust me in this."

He did. Waterproofed, he leaned against the wall in a real, beautifully tiled, modern bathroom, shut his eyes, breathed the steam, and felt the world swinging around an axis somewhere in the center of his skull.

He was possibly about to commit treason. Was that what you called it, when it was your species as well as your nation in question?

He was at least about to do something astonishingly foolhardy, going into this speech without one written note card for vocabulary, trusting adrenaline to hit and inspiration to arrive in his brain, when it wasn't entirely certain that he owned the strength necessary to make it downstairs or a vocabulary more extensive than occurred on that card. It was the evening, the fairly late evening, of a very, very long day, and the shower and the steam were reducing him to a very, very low ebb of willpower.

"Nand' paidhi," Tano called to him from outside the shower. "Nand' paidhi, I regret, you should come out now."

It was an atevi-engineered luxury, that literally inexhaustible hot water supply. And he had to leave it. Unfair. Unfair. Unfair.

He delayed the length of two long sighs, went out into the cruel brisk air and suffered the tape peeled; allowed himself to be unwrapped, toweled and, by now robbed of all modesty – and with the servants quite properly and respectfully professional – helped into his clothes: a silk shirt, re-tailored with a seam and fastenings up the arm, his coat, likewise sacrificed; soft, easy trousers of a modest and apolitical pale blue, a very good fit.

Once he'd sat down, too, a further toweling of his past-the-shoulders hair and a competently done braid, the only thing for which he'd habitually relied on his servants.

That was when the nerves began to wind tight. That was when he began to feel the old rush of adrenaline, a lawyer going into court, a diplomat going into critical negotiations. He was sitting, feeling the tugs at his hair as Tano plaited it, when Jago, wearing a black leather jacket despite the summer weather, arrived with a written message from Tabini, which said simply, There will be news cameras. Speak the truth. I have all confidence in you.

News cameras. One didn'tdamn the aiji to hell with the servants listening, no matter how one wanted to.

"Where's Banichi?" he asked. He was slipping toward combat-mode. He wanted everything that was his nailed down, accounted for, tallied and named. He knewTabini in his slipperiest mode. He wanted Banichi on his side of the fence, not Tabini's. He wanted to know what orders Banichi had, and from whom.

"I don't know, nadi," Jago said. "I only know I'm to escort you, nadi, when you're ready."

There was body armor and a weapon under that black leather coat, he was well sure. With feelings and suspicions understandably running high, it was entirely reasonable. And if Banichi wasn't with him, Banichi was up to something that left his junior partner in charge – possibly serving as Tabini's security, which Banichi also was. He had no way to know.

And no choice but the duty in front of him.

He gathered himself out of the chair and let Tano and the servants help him into the many-buttoned formal coat – which occasioned a little fuss with the discreetly placed fastenings that made the sleeve look relatively intact, and in order for the all-important ribbon-distinguished braid to lie outside the high collar. There were tweaks, there were adjustments, there were sly, curious and solemn looks.

He stood, to the ebon, godlike ladies around him, about the size of a nine-year-old. He felt entirely overwhelmed and fragile, and hoped, God, hoped he retained the things he needed in his head, and wouldn't – God help him – say or imply something disastrous tonight.

"Jago-ji, if you'd bring the computer – I don't think I'll need it, but something might come up."

"Yes," Jago said. "Are we ready, nand' paidhi?"

"I hope so," he said, and was surprised and even moved when Saidin bowed deeply, with: "All the staff wishes you success, nand' paidhi. Please do well for us."

"Nadi. nadiin." He bowed to the servants, who bowed with more than perfunctory courtesy. "You've made my work possible. Thank you ever so much for your courtesy and care."

"Nand' paidhi," the general murmur was. And a second all-round bow, on the tail of which Jago took him in charge, picked up the computer and headed him toward the outer chambers and the door. Tano, wearing a uniform identical to Jago's, overtook them just before the foyer.

Then it was out into the hall of porcelain flowers and down to the general security lift, which all the residents of the top two levels used, down the three floors to the broadest, most televised corridor in the Bu-javid, the entrance to the tashrid.

He was accustomed to the territory. His own office wasn't that far removed. But the halls were lighted from scaffolds supporting television cameras and crews, echoing with the goings and comings of staff and aides. If he'd felt overwhelmed by the servants, he was far more so here, in the entry to the hall itself, where the tall, elegant lords of the Association gathered and talked – more so, as silence fell where he and his escort walked, and became a quiet murmur at his back.

There was a lesser corridor, for the privileged not wishing to be accosted in the aisles, a way into the tashrid, the house of lords, down the division between that and the much larger chamber of the hasdrawad, the commons. The screen which divided the two chambers was folded back, affording direct access to the joined chambers, where he could walk past the stares and the murmurous gossip of the members, down the slant of the figured carpet to that small set of ornately carved benches set aside for dignitaries and invited witnesses and petitioners.

There on the front row of the dignitaries' gallery he could sit alone with his single note card, with the reassurance of Jago and Tano hovering in the standing area near him.

The lords of the Association and the elected representatives of the provinces were drifting in rapidly now. He directed his attention to the card he had yet to memorize, a handful of words that could convey what he wanted to convey without unwanted connotations, a handful of atevi-language definitions he'd devised. FTL was an absolute ticking bomb. He didn'twant to handle it tonight. He hoped to steer away from technicalities.