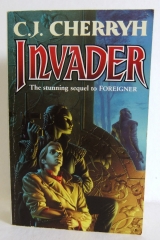

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

He called on the emergency phone, and Jago answered, but she said she had an appointment this afternoon, would tomorrow be acceptable? And he said, he didn't know why he said, that he couldn't wait, and he was going to get off at the floor where it was going.

Which eventually did come, and let out into a gray and brown haze in which he was totally lost. He called Jago on a phone that turned up, and Jago said, sorry, she would be there tomorrow. He'd have to wait. So he kept walking, certain that sitting still here would never get him to the meeting on time. He came to the turn in the lower hallway.

And became aware that his beast was following him, and that it was the hall outside his bedroom in Malguri. He was out of sandwiches. But the beast was hunting small vermin that ran along the edges of the hallway.

It passed him, snuffling for holes in the masonry, and left him in the dark, looking toward the crack of light that came from under his own bedroom door, beckoning him out of the nightmare and into the warmth of the familiar, if he could only get there. He walked and walked, and there always seemed progress, but he couldn't reach it. The light became the cold light of dawn, and then it was possible, but he had to leave, he had something to do, and couldn't remember what it was…

Thump.

His head jerked up. He blinked, looked about him in confusion.

"We're coming in, nand' paidhi," Tano said.

He looked out the window, at dark, at the lights of Shejidan, unable for a moment to understand how he'd come here. He moved a foot and felt his document case stowed quite safely where he'd put it.

He watched the city lights, the hills and heights and the city spread out like a carpet, all done with numbers. He hadmet such a person as the emeritus and he had a case full of papers – and the lights out there were all numbers.

He drifted off again during landing and was back in that hallway, looking for admittance to what he had to do. It was unjust that no one told him how to get inside. He began to be angry, and he went looking for Tabini to tell him things were badly arranged, and the paidhi needed…

But he couldn't remember what he needed. Things were shredding apart very badly. He was just walking down a hall and the doors were very far apart.

Bump. The wheels were on the ground. He saw the field lights ripping past the window. The paidhi traveled at jet speeds. The paidhi's mind didn't.

But he'd had no time. He'd had to get home.

Blink and he was in Malguri. Blink and the plane was slowing for the turn onto the taxiway. Lights going past one another, blue and white and red.

CHAPTER 16

It was so troubling a dream he couldn't shake it, not even at the aiji-dowager's breakfast table – he sat in the open summer air, with the dawn coming up over the Bergid, applying preserves to a piece of bread and thinking about beasts and bedrooms, astronomers and city lights and mecheiti, until Disidi gave him a curious look, rapped the teacup with her knife, and inquired if he were communing with the ship.

"No," he said quickly. "Your pardon, nand' dowager."

"You're losing weight," Ilisidi said. "Eat. So nice to see you with that clumsy thing off your arm. Get your health back. Exercise. Eat."

He had a bite of the toast. Two. He was hungry this morning. And he hadhad a decent sleep. He had his wits about him, such as they ever served to fend off Ilisidi's razor intellect – even if he had spent the night walking hallways in company with a creature whose whole kind might be extinct. It was a very, very old piece of taxidermy. So he'd assumed in Malguri.

"Young man," Ilisidi said. "Come. Is it business? Or is it another question wandering the paths of intellect?"

"Nand' dowager," he said, "I was wondering last night about the staff's welfare at Malguri. Do you have word on them? Are Djinana and Maigi well?"

"Quite well," Ilisidi said.

"I'm very glad."

"I'll convey your concern to them. Have the fruit. It's quite good."

He remembered Banichi chiding him about salad courses. And Hanks' damn pregnant calendar.

"So why do you ask?" Ilisidi asked him.

"A human concern. A neurotic wish, perhaps, for one's good memories to stay undimmed by future events."

"Or further information?"

"Perhaps."

The dowager always asked more than she answered. He didn't press the matter with her, fearing to lose her interest in him.

"And Nokhada? And Babsidi?"

"Perfectly fine. Why should you ask?"

The gardened and tile-roofed interior of the Bu-javid marched away downhill from the balcony, soft-edged with first light, and there was a muttering of thunder, though the sky was clear as far as the Bergid: it presaged clouds in the west, hidden by the roofs.

He hadn't called Hanks on his return. He wasn't in a charitable mood for Hanks' illusions, or gifted with enough concentration for Hanks' economics report, in any form.

He still couldn't get a call through to his mother. He'd tried, and the notoriously political phone service was having difficulties this morning. Could he possibly wonder that the gremlins manifested only on the link to the mainland?

The note the Foreign Office had slipped him declared nothing helpful, just that his suspicions were correct: nothing was being decided where it had a damn chance to be sane, in the normal course of advisory councils and university personnel who actually knew history and knew atevi; everything wasbeing decided behind closed doors and in secret meetings of people who weren't elected, hadn't the will of the people, and were going to, he'd bet his life on it, maneuver to cast everything into the hands of the ship, the station, and those willing to relocate there.

And, worrisome small matter, Jase Graham hadn't called back.

"So?" Ilisidi asked. "You've talked with these ship folk. And now they land."

"Two of them. You've gotten my translations."

"To be sure. But they don't answer questions well, do they? Who are they? What do they want? Why did they come back? And why should we care?"

"Well, for one most critical thing, aiji-ma, they've been to places the Determinists have staked a great deal can't exist, they want to export labor off the planet, they want atevi to sell them the materials to make them masters of the universe, and they probably think they can get it cheap because humans on Mospheira weren't talking as if atevi have any say in the business."

"Too bad," Ilisidi said, dicing an egg onto her toast. "So? What does the paidhi advise us? Shall we all rush to arms? Perhaps sell vacation homes on Malguri grounds, for visiting humans?"

"The hell with that," he said, and saw Ilisidi's mouth quirk.

"So?" Ilisidi said, not, after all, preoccupied with her breakfast.

"I have some hope in this notion of paidhiin from the ship. I think it's a very good idea. I can have direct influence at least on Graham, and he seems a sensible, safety-concerned individual. If nothing else, maybe I can scare hell out of him – or her – and have more common sense than I'm hearing out of Mospheira."

"Scare hell out of Hanks-paidhi," Ilisidi said. "That's a beginning."

"I wish I could. I've tried. She's new. She's quite possibly competent in economics —"

"And she has powerful backers."

"I have freely admitted to it."

"Amazing." Ilisidi held her cup out for her servant to refill. "Tea, nand' paidhi?"

He took the offering. "Thank you. – Dowager-ma, may a presumptuous human ask your opinion?"

"Mine? Now what should my opinion sway? Affairs of state?"

"Lord Geigi. I'm concerned for him."

"For that melon-headed man?"

"Who – nevertheless occupies a sensitive and conservative position. Whom – a pretender to my office has needlessly upset."

"Melon-heads all. Full of seeds and pulp. The universe of stars is boundless. Or it is not. Certainly it doesn't consult us."

"That sums up the argument."

"Do humans in their wisdom know the universe of stars?"

"I – don't know." He wasn't ready to tread in that territory. Not for any lure. "I know there are humans who study such things. I'd be surprised if anyone definitively knew the universe."

"Oh, but it's simple to Geigi. Things add. They have it all summed and totaled, these Determinists."

"Does the dowager chance to have access to Determinists?" Many of the lords paid mathematicians and counters of every ilk, never to be surprised by controversy.

Certainly Tabini's house had a fair sampling of such experts, and he'd bet his retirement that Ilisidi had.

"Now what would the paidhi want with Determinists? To illumine their darkness? To mend their fallacious ways?"

"Hanks-paidhi made an injudicious comment, relative to numbers exceeding the light constant. I know you must have certain numerological experts on your staff, skilled people —"

More toast arrived at Ilisidi's elbow. And slid onto her plate to an accompaniment of sausages. "Skilled damned nonsense. Limiting the illimitable is folly."

"Skilled people," Bren reprised, refusing diversion, "to explain how a ship can get from one place to another faster than light travels – which classic physics says —"

"Oh, posh, posh, classic folly. Such extraneous things you humans entrain. I could have lived quite content without these ridiculous numbers. Or, I will tell you, lord Geigi's despondent messages."

"Despondent?"

"Desperate, rather. Shall I confide the damage that woman has done? He's trying to borrow money secretly. He's quite terrified, perceiving that he's consulted a person of infelicitous numbers, a person, moreover, who let her proposals and his finances become too public – he's quite, quite exposed. Folly. Absolute folly."

"I'm distressed for him."

"Oh, none more distressed than his creditors, who thought him stable enough to be a long-term risk as aiji of his province; now they perceive him as a short-term and, very high risk, with his credit andhis potential for paying his debts sinking by the hour. The man is up for sale. It's widely known. It's very shameful. Probably I shall help him. But I dislike to trade in loyalties and cash."

"I quite understand that. But I find him a brave man – 1 and possibly trying to protect others in his man'chi."'

"Posh, what do you understand? You've no atevi sensibilities."

"I can help him. I think I can help him, dowager-ji. I think I've found a way to explain Hanks' remark… if I had very wise mathematicians, correctmathematicians from the Determinists' point of view…"

"Are you asking me to find such people?"

"I fear none of that philosophy have cast their lot with your grandson. You, on the other hand…"

"Tabini asks me to rescue this foolish man."

"I ask you. Personally. Tabini knows nothing about it. Rescue him. Don't buy him. Don't take a public posture. Don't say that I suggested it. Surely he could never accept it."

"Why?" Ilisidi asked. "Is thisthe mysterious trip to the north?"

"I'd be astonished if I ever achieved mystery to you, nand' dowager."

"Impudent rascal. So you were out there rescuing Geigi the melon?"

"Yes."

"Why, in the name of the felicitous gods?"

He couldn't say in terms he knew she couldn't misapprehend. He looked out toward the Bergid, where dawn was turning the sky faintly blue. "There's no value," he discovered himself saying, finally, "in the collapse of any part of the present order of things. The world has achieved a certain harmony. Stability favors atevi interests. Yours, your grandson's. Everyone's. Stability even favors Mospheira, if certain Mospheirans weren't acting like fools."

"This woman is a wonder," Ilisidi said. "She should have sought me out. But she had no notion she should."

"She's harmless on Mospheira. Where I'd like to send her. But in moments of fright, my government freezes solid. This is such a moment. Let me tell you, dowager-ji, one secret truth of humans: we have self-interests, and truly selfish and wicked humans can be far more selfish than atevi psychology can readily comprehend."

"Ah. And are atevi immune?"

"Far more loyal to certain interests. Humans can be thorough rebels, acting alone and in total self-interest."

"So can atevi be great fools. And if Geigi believed this woman, still I wonder why you took this very long, very urgent excursion, and sought advice of such eccentrics."

"A brilliant old man, nand' dowager. I recommend him to your attention."

"An astronomer"Ilisidi said with scorn.

"Possibly a brilliant man, aiji-ma. I'd almost have brought him back to court, aiji-ma, but I feared court was too fierce a place for him. His name is Grigiji. He's spent a long life looking for a reconciliation of human science and atevi numbers. His colleagues at the observatory have devoted themselves to recovering the respectability of atevi astronomers. They want to create an atevi science that uses atevi numerical concepts to look past human approximations… approximations which I will assure you humans do use, from time to time… to an integration of very vast numbers with the numbers of. daily life."

He said what he said with calculation, in hope of catching Ilisidi's interest in things atevi, and in atevi tradition. And he saw the dowager paying more than casual interest for that one instant, the mask of indifference set aside.

"So?" Ilisidi asked. "So what does this Grigiji say to Geigi?"

Ilisidi was intellectual enough to set aside beliefs that didn't gibe with reality, politician enough to accept some for political necessity; and atevi enough, he suddenly thought, to long for some unifying logic in her world, logic which the very traditions she championed declared to exist.

He reached inside his coat and found the small packet he'd made, copies of the emeritus' equations and his own notes such as he'd been able to render them. She didn't reach for it: the wind was blowing.

"What is this?" Ilisidi asked.

"A human's poorly copied notation of what the astronomer emeritus had to say. And his own words, aiji-ma." A servant, young and male – Ilisidi's habit – showed up at his elbow to take the papers into safekeeping.

"Not the astronomer-aiji?"

It was a gibe. Is there some reason, the question meant, that Tabini's own astronomers, high in the court, failed – and a human sought his sources elsewhere? Doubtless this very moment, Cenedi would be sending out inquiries about Grigiji, his provenance, his background, his affiliations. And Ilisidi, who habitually gave the paidhi a great deal of tolerance, but – propositioned – would notcommit herself to touch such an obviously political gift: clearly the paidhi was being political; so, in turn, was she.

"Nand' dowager," he answered her carefully, "the aiji's own astronomers have other areas of study. And they're not independent. This man, as I understand, and this observatory, have been the principal astronomers engaged on this research. They're not affiliated with any outside agency. This is an exact copy of what I brought your grandson, nothing left out, nothing added. May I ask the dowager – to advise me?"

Ilisidi's hand left the teacup for an insouciant motion. Proceed, she signaled.

"Understand, aiji-ma, I'm not a mathematician. Far from it. But as I understand both what humans have observed and what this man has been attempting to describe in numbers – as I was flying into the city last night, I saw the lights, high places, low places of the city, lights like the stars shining in dark space." He knew Ilisidi had flown at night – very recently – into Shejidan. "I saw – out the airplane window, in those lights in high and low spots, all over Shejidan – what humans have described with their numbers. And what Grigiji's vision also describes, as I faintly understand it. His answer to lord Geigi."

"In the city lights. Writ in luminous equations, perhaps?"

"The paradox of faster-than-light, aiji-ma; say that the universe doesn't stretch out like a flat sheet of black cloth. That it has – features, like mountains, like valleys. Say there's a topology of such places. Stars are so heavy in this sheet they make deep valleys. Therefore the numbers describing the path of light across this sheet are quite, quite true. One doesn't violate the Determinists' universe: light can't go faster, by the paths that light must follow. Light and all things within the sheet that is this universe follow those mountains, and take the time they need to take. So nothing that travels along that sheet violates the speed of light. One can measure the distances across the sheet, and they are valid. Right now the effects of atmosphere diminish the accuracy of atevi observations, but when one observes from the station – as atevi will – the accuracy will be far, far greater."

"You're buying time," Ilisidi said, with another small quirk of the mouth, a flash of golden eyes. "You very rascal, you're setting it on a shelf they can't reach."

"But it is true, nand' dowager, and up there they'll prove it. Those papers, as I understand what I'm told, describe that sheet I'm talking about in terms that admit of space not involved in that sheet. What we call folded space."

"Folded space. Space folds."

"A convenience. A way of seeing it for people who aren't as mathematical as atevi, people whose language doesn't express what that paper expresses. It's the way starships travel, aiji-ma. It's the highest of our high technology, and an ateva may have foundit without human help – if I could read those notations I copied. Which I can't, because I don't have the ability an ateva mathematician has to describe the universe."

"Your madman told you this."

"Aiji-ma, light doesn't travel in a straight line. But because light is how we see, how we define shape, how we measure distance, over huge scale – that makes space act flat."

"Makes space act flat."

"We don't operate on a scale on which the curves normally matter. Like a slow rise of the land. The land still looks flat. But the legs feel the climb. Scale makes the difference to the viewer. Not to the math. Not to the hiker's legs."

Ilisidi regarded him with a shake of her head. "Such a creature you are. Such a creature. And not in touch with your university. Done it all yourself, have you."

"I knowthe essence of things I can't explain by mathematics, 'Sidi-ma." To his dismay he let slip the familiar name, the way he held the dowager in his mind. And didn't know how to cover it. "You show your children far more complex things than they have the mathematics to understand. That's the way I learned. That's what I have to draw on. A child's knowledge of how his ancestors moved between the stars. They didn't teach me to fly starships. I just know why they work."

"Faster-than-light."

"Much faster than light."

"Do you know, paidhi, an old reprobate such as myself could ask to what extent all this celestial mapmaking is new, and how much humans were prepared to give at this juncture. You certainly aren't using Hanks-paidhi for a decoy, are you?"

"Nand' dowager, on my reputation and my goodwill to you, I emphatically did notclear Hanks-paidhi to leak that to Geigi. And I didn't clear with my Department what I've just told you."

" Whencethis astronomer, whenceGeigi's dilemma, at the very moment this ship beckons in the heavens – when you need the goodwill of such as myself, nand' paidhi? Is this my grandson's planning? Is this one of his adherents?"

He was in, perhaps, the greatest danger he had ever realized in his life, including bombs falling next to him.

The daylight had increased as they sat, and those remarkable eyes, so mapped about with years, were absolutely cold. One didn't betray 'Sidi-ji and live to profit from it. One didn't betray Cenedi and harm Ilisidi's interests – and walk free.

Ilisidi snapped her fingers. A servant, one of Cenedi's, he was sure, brought a teapot and poured for each of them.

He looked Ilisidi in the eyes as he drank, the whole cup, and set the cup aside.

"So?" Ilisidi asked.

"Nand' dowager, if it's Tabini's planning, his means eludes me. This is an old and respected man in his district, no new creation, that I detected."

"Then what is your explanation? Why this coincidence?"

"Simply that the man may be right, nand' dowager. The man may have found the truth, for what I know. I'm not a mathematician – but I should never wonder at someone finding what really exists."

"At the convenient moment? At this exactly convenient moment for him to do so? And my grandson had nocollusion with humans to slip this cataclysm in on us, to destroy a tenet of Determinist belief?"

"It doesn't destroy it! By what I can tell, it doesn't destroy it, it supports it."

"So you've been told. And you just happen to rush out where a man has just happened to find the truth."

"Not 'just happened,' nand' dowager. Not'just happened.' It's the whole progress of our history behind this man. We've not been transferring just thingsinto atevi hands. We've transferred our designs and our mathematical knowledge to a people who've proceeded much more slowly in their science than humans did withoutatevi skill at numbers – a speed we managed because we dead-reckon, approximate, and proceed as atevi won't. One can do this – when one builds steam engines and builds things stronger than economical, rather man risk calamity. We were astonished that you took so long to advance. We watched the debates over numbers. We waited."

"For us poor savages."

"We thought so in the beginning. We couldn't figure why you couldn't just accept what we knew as fact, keep quiet, and build by our designs – but the point is, it wasn't fact, it was very close approximation. And atevi demanded to understand. Then, then, we began to realize it wasn't just the designs we were transferring: you were extracting our numbers, refining them in an atevi conceptualization that we knew was going to break out someday in a way we didn't foresee. When we gave you the computers that most humans use to figure simple household accounts, you questioned our logical designs. We knew there'd come a day, an insight, a moment, that you'd make a leap of understanding we might not follow. Not in engineering, perhaps. You are such immaculate perfectionists, when our approximations will bear traffic and hold back the waters of a lake; but in the pure application of numbers – no, I'm not in the least shocked that a breakthrough has come at this moment, not even that it's come in astronomy, in which we've had the very leastdirect contact with your scientists. We gave atevi mathematicians computers. We knew study was going on. It never surprised me that the Determinists hold the speed of light as a matter of importance: it is important; it's far from surprising that astronomers seeking precision in their measurements are using it and discovering new truths —"

Air seemed scant. He was walking a ledge far past his own scientific expertise – far beyond his ability to prove – and on a major, dangerous point of atevi belief.

"I don't know these things, aiji-ma. I'd wish the astronomers of the Bergid and the scholars on Mospheira could talk to each other. But I'm the only one who could translate. And the emeritus was using mathematical symbols I don't remotely know how to render – I'm not even sure human mathematics has direct equivalents. I suspect some of them are couched in the Ragi language, and if they rely on me to get them into Mosphei', humans are never going to understand."

"Such delicate modesty."

"No. Reality. Most humans don't speak your language, aiji-ma, because most humans aren't nearly as good in math as I am. You view it as so important to know those numbers – and we don't, aiji-ma. We can't add that fast in our heads. We haveto approximate – not that we're disrespectful of atevi concepts; we just can't add that fast. Our language doesn't have your requirements, your expressions, your concepts. At times my brain aches just talking with you – and for a human, I'm not stupid. But I'm working as hard as I can sometimes just talking to you, especially about math – far from conveying folded-space mathematics to anyone whose symbols I can't remotely read, nand' dowager. I'm reduced to asking the man's young students what he said and finding out that theydon't understand all he says, even with their advantage in processing the language."

There was long silence, once he stopped talking. Long silence. Ilisidi simply sat and stared at him. Wind stirred the edge of the tablecloth, and blew the scent of diossi flowers to the table.

"Cenedi will see you out," Ilisidi said.

"Nand' dowager," he said, feeling both fear – and real sadness in his sense of failure. He rose from the table, bowed, and went to the door and inside the apartment.

Cenedi met him there.

"I've offended her," he said to Cenedi quietly. "Cenedi-ji, she doubts me."

"Justly?" Cenedi did him the courtesy of asking.

"No," he said fervently. "No. But I can't make her understand I'm not smart enough to do what she thinks I've done. I may have given her the ravings of a madman. I hope I haven't. But I can't read his writings to judge. I could only copy them. I can't judge the quality of it. I don't know what I've given her. I hoped it would do some good."

"One heard," Cenedi said as they crossed the room toward the door.

"At least – tell her I wish her well, and hope for her eventual good regard."

"One will pass the message," Cenedi said, "nand' paidhi."

Banichi picked him up – and asked, since the paidhi wasn't bothering to put on a cheerful face, not how it had gone, but what had happened; and he could only shrug and say, "Nothing good, Banichi. I did something wrong. I can't tell what."

Banichi answered nothing to that. He thought Banichi might try to find out where he'd misstepped – easier for Banichi to ask Cenedi outright, since Banichi had the hardwiring to understand the answer. But it seemed to a human's unatevi senses that he'd simply pushed Ilisidi too far and given her the suspicion she'd very plainly voiced to him: that he was Tabini's, a given; that the whole Hanks business was a setup possibly engineered by Tabini himself; and one could leap from that point to the logical conclusion that if Hanks was a setup designed to push atevi faster than the conservatives wanted to go, it couldn't happen without Bren-paidhi being in on it.

Which meant – perhaps – that in Ilisidi's mind all the relations she had had with him were in question, including how far he'd be willing to go to sweep Ilisidi away from her natural allies. Never mind the broken shoulder: Ilisidi was surrounded by persons of extreme man'chi, persons who'd fling themselves between Ilisidi and a bullet without an editing thought: she was usedto people who took risks. She might not know humans as well as Tabini, but she had expectations of atevi and she had experience of Tabini that might lead her at least to question, and not to risk her dignity or her credibility on someone not within her man'chi.

She hadn't poisoned him. He'd not flinched from the possibility. He'd surely scored points in that regard. But he'd trod all over atevi beliefs, atevi pride – which with Ilisidi was very personal: Ilisidi had unbent with him a little and he'd used that, or advantaged himself of it, and asked the dowager to support Tabini —

The wonder was she hadn't poisoned him. And he was attached to Ilisidi – he didn't know exactly how it had happened, but he was as upset at her accusation of him as he'd be if he'd somehow crossed the other atevi he'd grown close to.

Which didn't include, somehow, Tabini. Not in that sense of reliance and intimacy. Not in the sense that —

That he'd damn well regretted Jago had left his room night before last, experimentation untried. And he was mortally glad Jago had stayed out of his close company the last two days.

But he longed to find her alone and find out what she did think, and whether she was upset, or embarrassed, which he didn't want; and didn't want to risk the relationship he had with her and with Banichi, without which – he was completely —

Alone.

And scared stiff.

From moment to moment this morning he dreaded the intrusion of other humans. He didn't know what to do if the interface went bad. He hada certain security in his atevi associates and he had to spend, hereafter, the bulk of his free time, such as it was, teaching a foreign human what that foreign human might not ever really understand.

After which, in a number of years, Jase Graham boarded an earth-to-orbit craft and went back to his ship, leaving the paidhi – whatever the paidhi had left.

He was in a major funk, was what had hit him. Two days ago he'd looked forward to Graham's arrival as the panacea for his troubles. But that was when at least his atevi world had been holding together.

And the paidhi always had that image of the clock stopped. The ultimate, shocked surprise of that moment that atevi had reacted in self-preserving attack on the very humans who really, really likedatevi.

He had to get his mind back in order, his hurts and his self-will packed back in their little boxes, and, God, most of all he couldn't let himself start brooding over how much atevi didn't likehim. Ilisidi never had likedhim. Ilisidi had found him amusing, entertaining, informative, a dozen other things – and now he wasn't. Now things were too serious. Humans were coming down from the sky. Ilisidi had decisions to make and she'd make them for atevi reasons. If he had a duty, it was to inform Tabini of Ilisidi's reaction.

And Ilisidi knew it.

"Banichi-ji, Ilisidi asked me —" One didn't say suspects, didn't say, implied: when the paidhi was deep in the mazes of atevi thought, the paidhi said exactly what hadhappened, not what he interpreted to have happened. "– asked me whether Tabini had set Hanks-paidhi, Geigi, the question, the astronomer happening to come up with a possible answer and all at this crisis."

There was silence for a moment. Banichi drew a long, audible breath as they walked. "Such a tangled suspicion."

"She may have been angry. Under the theory that I may simply have angered her with a social blunder, perhaps you could inquire of Cenedi the cause of her displeasure with me."

"Possible. One might ask. This befell when you gave her the calculations."