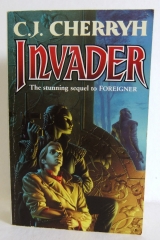

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

"She wouldn't touch them herself. A servant took them before they either blew away or I had to take them back."

"She suspected their content."

"She said she suspected the emeritus as Tabini's creation. I tried to assure her I haven't the fluency or the mathematical knowledge to have understood the reasoning in my own language, let alone to have translated them into this one. The fact that I don't have the concepts is why I went out there in the first place, for God's sake."

"I'll pass that along," Banichi said.

By which Banichi assuredly meant to Tabini. Possibly back again to Cenedi.

"I truly regard the woman highly."

"Oh, so does Tabini," Banichi said. "But one never discounts her."

CHAPTER 17

It wasn't an easy thought to chase out of one's mind, Ilisidi's potential animosity, no more than it was easy to avoid comparisons with Tabini's interested reception of the papers. Tabini had sent him a verbal message at the crack of dawn, by Naidiri himself, Tabini's personal bodyguard, stating confidentially that in the aiji's opinion, the emeritus' papers at least presented the numbers-people something to chase for a good long while, it was the craziest proposal Tabini personally had ever seen, and the aiji was sending security to watch over the observatory.

Which he didn't forget in the context of his falling-out with Ilisidi. He didn't like to think of the likes of the Guild moving in on the little village and disturbing the place – because it wouldn't be Guild members like Cenedi and Banichi, who had the polite finesse to make a person truly believe they were off duty when they never were; he didn't like to think of the place destroyed by his brief attention to it, or the astronomers' lives changed irrevocably for the worse.

But security for the observatory was nothing he should or could protest: he'd been chasing the numbers too concentratedly even to think how the importance of the place had suddenly changed, when the old man had come rushing in with his answer: Grigiji had become someone valuable to Tabini, and therefore a target, as everything Tabini touched directly or indirectly was a target. He'd forgotten, in the delusion he could seek an answer for Geigi on his own, and slip it – God, it seemed naive now – into Ilisidi's hands with no untoward result.

The paidhi had been a thoroughgoing fool. The paidhi had not only blown up bridges with Ilisidi, he'd put the observatory and Grigiji at risk, possibly done something completely uncalculated regarding Geigi and Geigi's province and Geigi's relationship to Ilisidi and to Tabini – the paidhi was consequently thoroughly depressed, thoroughly disgusted with his quick and perhaps now very costly feint aside to chase what had looked like a good idea at the time.

The way for the paidhi to do what Wilson-paidhi hadn't been able to and Hanks-paidhi couldn't: get the conservative atevi and Tabini's faction simultaneously behind an idea.

The hero's touch. The heroics he'd accused Hanks of, that Hanks had come back at him with – and by what he saw now, Hanks had had the right of it.

Hanks deserved a phone call, at least to set up a meeting to brief her on the essentials, and on what a hash he might have made of her slip with Geigi. It wasn't going to be easy to explain, it wasn't going to be pleasant, and he wasn't ready to cope with it. Not yet.

He sat down to go through the message stack – the new office was actually settling in to work, and he had a number of appreciations for the cards he'd sent; the table in the foyer was overflowing with the traditional gifts of flowers from the new employees, so many they'd accumulated in a tasteful bow about the table and in other areas of the floor where they wouldn't impede traffic, and he supposed he ought to have been cheered, but his arm ached, his ribs ached, and breakfast wasn't sitting well. He asked Algini for his computer, took his correspondence to the sitting room, and sat and prepared reports, and reports.

Saidin quietly adjusted the windows for ventilation and light, and set a fan to operation. He'd grown less distracted by the comings and goings of the staff. He almost failed to notice, until Saidin crossed between him and the light.

"I need to speak to Banichi, nand' Saidin," he said. He wanted a time for leisurely discussion. "Is he back yet?"

"Not yet, nand' paidhi. Algini is on duty."

"Jago?"

"I believe she went down to the Guild offices, nadi. One could send."

"No," he said. "It's not urgent." His eyes were tired, and among his messages was an advisement Tabini was directing the mathematics faculty to look at Grigiji's notes. And hisnotes, which he hoped he hadn't mis-copied. He'd protested that to Tabini and urged him if there were mistakes to attribute them to human copying, not Grigiji's math.

Among his messages was an extensive new transcript from the ship, which contained more document transmissions between Mospheira and the ship, more of Mospheira's very specific questions about origins and direction of travel and findings – which the ship hadn't answered fully. There was a direct question about the supposed other station and its location, and whether – a question that hadn't even occurred seriously to him – the ship might have left the solar system at all, but whether it might in fact have established the long-threatened base at Maudette, the red, desolate further-out planet atevi called Esili – the planet to which, before the Landing, the Pilots' Guild had wanted to move the colony rather than have it land on the atevi world.

No, the ship said. It had visited another star. There was no base at Maudette.

Which star? the President wanted to know, and named several near ones.

The Guild said, logically enough, that they had no such names on file; then asked for star charts with atevi names. And renewed the discussion about landing sites – in regard to which the ship wanted general maps and names.

Which Mospheira, in a sudden reticence, refused to provide until the ship was forthcoming with star charts.

At which point the woman Yolanda Mercheson came on com, wishing to speak to the President.

And the President was quite pleasant. Quite encouraging. The President said he advised a landing on Mospheira as the best way to guarantee human sovereignty – and Mercheson said she'd present that view.

Then Mercheson presented a shopping list of raw materials and asked pointedly if Mospheira had those goods.

The President didn't know. The President would get back to her with that information, but he knew they had some extensive stockpiles of materials.

Stockpiles.

Flash of dark. Terror. Pain. Cold metal and a looming shadow, asking him… accusing him…

Most clearly you're stockpiling metals. You increase your demands for steel, for gold– you give us industries, and you trade us microcircuits for graphite, for titanium, aluminum, palladium, elements we didn't know existed a hundred years ago, and, thanks to you, now we have a use for. Now you import them, minerals that don't exist on Mospheira, For what? For what do you use these things, if not the same things you've taught us—

Barrel of a gun against his head. A question he'd taken at face value at that moment, and pain and fear had wiped out the context – no, he hadn't knownthe context at that moment, he hadn't knownthe ship had returned to atevi skies, he hadn't knownthe situation the interrogator was implying… space-age stockpiles for an event the whole human population of the planet might have been waiting to spring on atevi. At that terrorized, dreadful moment he'd thought only… aircraft. Only… a hidden launch program. Only… of dying there. And he hadn't half-remembered the question in the light of what he'd learned later.

Stockpiles – of goods critical to a space program.

He'd protested he wasn't an engineer, he didn't know… and the interrogator had said… you slip numbers into the dataflow. You encourage sectarian debates to delay us…

The argument of Ilisidi's allies. Ilisidi's constituency, the constituency Ilisidi had ostensibly betrayed – but never count an ateva to have changed sides completely. There were always points of stress in an association.

Sectarian debates to delay us…

And he'd said… We build test vehicles. Models. Wetest what we think we understand before we give advice that will let some ateva blow himself to bits, nadi…

He'd thought that was all the truth. He'd told that to an interrogator whose identity he still didn't know, a man who might have been Ilisidi's, or a partisan of someone affiliated to Ilisidi.

He'd hadn't known then… about the ship. He hadn't understood the matter about sectarian debates. Or the significance of stockpiles of materials for a space program. He'dtalked to them about aircraft. He'dmaintained human innocence…

He lost his place in the tape. His fingers were cold as he punched buttons and ran it back, and heard the section through again, and knewhe'd promised Ilisidi along with Tabini a transcript of all his translations.

Stockpiles… the atevi held to be extensive. Stockpiles of minerals Mospheira didn't otherwise have…

Stockpiles begun – God knew how long ago. The paidhi, on informed opinion, didn't believethey could be that extensive, since the paidhi knew with fair certainty what had generally gone to Mospheira and what Mospheira would use – unless there were Defense Department secrets too deep and too old for the current paidhi to know, or trading – as could sometimes happen – that didn't get reported accurately to Shejidan.

There were bunkers in the high center of Mospheira, places fenced off from hikers and guarded by people with guns, which citizens accepted – you didn't go there. You didn't mess with those perimeters. They were antiquated, increasingly so, in an increasingly peaceful world – at least – the idea of air raid shelters seemed antiquated, in his generation. But there'd been fear of atevi landings on the beaches before there'd been aircraft.

There'd been fear of atevi air attacks, when they'd given atevi aviation, and situated aircraft manufacturing on the mainland. The bunkers were supposed to be nerve centers, critical command posts, things to make sure no attack ever drove humans to the brink of extinction again.

They saidthey were command posts. Nothing about how deep they were, how extensive they were – or what they contained. And ifthey contained what he'd been asked about, if there were stockpiles the President of Mospheira could use to deal with the ship —

Mospheira couldn'tcall the aiji's bluff. He couldn'thave set Tabini up to make a threat of boycott and have Mospheira go around the obstacle with some damned antique storage dump.

But it was supply. Even if it existed – it didn't manufacture itself. The manufacturing plants that did exist on Mospheira couldn't be converted at a snap of the fingers to do what they hadn't been designed to do —

But Mospheira didn't educate the paidhiin in what the Defense Department did, or had, or wanted: it was specifically excluded, that area of inquiry. And when the government and State specifically cleared some plastics factory on the East Frontage for ecological impact – you trusted they were making domestic-use articles.

The Department sent the paidhiin into the field not knowing that for an absolute, examined fact. The paidhiin knew there were no death rays. He knew that as an article of faith. There were no nuclear installations. There were no truly exotic sites: the colonists hadn't had those kind of weapons and hadn't given atevi a nuclear capability… yet.

But this talk of stockpiles made a chill down his back, and told him the paidhi might for once in a career of mandated consultations before moving truly need to consult – and might now, if his current actions hadn't set the Defense Department on its ear and sent the Secretary of Defense straight to the President's door with a reckoning of exactly how far and with what offer to the spacefarers they could call Tabini's hand and defy a boycott.

Dammit, he couldn't trust his files regarding a history he had no idea whether the censor Seekers had reached, or not reached – he couldn't trust what he'd been told. How did the paidhi even trust that his own education hadn't censored or even lied about vital facts? Once censorship was at issue – how did anyone, any official trust how far it would go, when it would have begun, whose information it would have censored, or what it would have constructed as a substitute for the truth? Humans had come close to annihilation. They hadn'thad weapons. Atevi in the early days couldn't trade them aluminum or titanium or any space-age material. Mospheirans could get plastics, they could get anything vegetable fiber could produce, anything they could get from limited drilling along the North Shore; they had solar energy and electricity, but they hadn't been set up to realize a need two centuries along and slip enough into storage to hold out against the interlinking of the Mospheiran/atevi economies —

Mospheirans hadn't, all along, been that damn canny, that damn persistent, or that damned concerned about their future – the radicals might wish they'd been, the radicals might have a fantasy they'd been, and maybe something did exist in stockpiles, but it didn't translate to real capacity to hold against an atevi cutoff of supplies —

– or to anticipate some traitorous paidhi cutting a deal with Phoenixand trying to exclude Mospheira, all for the planetary good. They couldn'thave him boxed in. Neversay to atevi at large that the aiji had made a threat he couldn't back or a promise that made him look foolish. Blood could flow in the streets if that happened. Blood was ready to flow in the streets, if he made such a mistake.

He wrote, Aiji-ma, regarding the most recent ship conversations with Mospheira, the expected behind the doors negotiations have proposed human stockpiles of materials I have proposed you threaten to withhold. My hope based on experience living on and traveling on the island is that they're small, not containing everything a space program needs, and that they might be used for bargaining and for attempting to attract the ship to their point of view, and that the Mospheiran government might exaggerate their size in an attempt to get a better agreement.

This, however, does not guarantee I am right about their size. If they should be larger, I have advised you badly, and you must take whatever measures you deem appropriate.

On the other hand, the ship can determine even buried reserves from orbit, as well as the character of factories. It is my hope that factories are not sufficient even if such stockpiles exist, and that they cannot be built in a timely enough fashion to satisfy the ship's leaders.

Further, we have presented the ship extensive political reasons to accept your conditions.

But I am dismayed to know now that I was asked about this matter in Malguri and did not at the time realize its impori, nor recall it in preparing my estimates and advisements to you. I am completely to blame for any negative result. I have erred once today in estimating the dowager's response, as I believe Banichi will have told you. At the reading of the enclosed transcript you may judge I have erred repeatedly and egregiously. If this is so, I urge you not to listen to me further, and to take my advice as that of an underinformed official to whom his own government has not confided sufficient truth to rely upon.

I feel I have no recourse now but to write the dowager, and I have given a firm pledge to do so. But I shall delay my response and take the disgrace on myself for doing so, in hopes that events or greater wisdom than mine will find a means for you to secure your own interests in advance of my fulfilling a rash promise that may have placed me in a position incompatible with your best interests. If I were placed under arrest, I could not send such a message, aiji-ma.

Please believe, as I have in profound embarrassment urged upon llisidi, that I wished to do good for her and for you, and that it is not through hostile intent or orders of my government that I have done what I have done.

It was not a cheerful message to have to write. He appended the transcript. He sent the message, via his remote, to the aiji's fax, rather than using courier, if for nothing else, that propriety mattered less than speed of getting that message next door.

He sat staring at the blowing curtains and asking himself, with a certain tightness in the throat, how far he could impose on atevi patience.

Or how far he could even believe in his own increasingly remote attenuation of logic.

He knew what interests he was fighting on Mospheira. He hadn't been utterly sure until Shawn's message turned up – but that confirmed he'd guessed right, that far, once the ship was in the equation, exactly where the pressure would come from and who would apply it. He just —

– had reached the end of his personal credit, his personal ability, his personal strength, and he'd made a couple of mistakes in his sudden downhill rush to get the landing finalized that had cost him, personally, cost Tabini, personally, cost Ilisidi, and might cost political credit and lives across an entire atevi and human world before the shock waves settled.

Where did he thinkhe could go setting up an atevi way to see the universe – knowing, God help him, that the old, old wisdom in the Department had always held that atevi would make some conceptual break and go spiraling off into a mathematical dark where humans weren't going to understand. And where in human helldid he think that point of departure was likeliest going to come if not in the highest, most esoteric math – which he, in his personal brilliance, had gone kiting off to beg of the persons most likely to come up with it —

Good merciful God, what did he expect but upset when he tossed the mathematical bombshell into the capital, the court, the touchiest political maneuvering of the last century – and let it lie on the breakfast table of the ateva least likely to benefit?

How in hell did he reconcile that little gift with his emotional appeal for 'Sidi-ji to rise above politics, rise to the good of the Association, sacrifice herself on the altar of her grandson's success?

He'd done that, after what he'd adequately remembered once prompted, and he hadn't seen it? Damned right he hadn't drawn the two threads together, when a faster mind could have anticipated Mospheira would fight back on the boycott issue. He should have asked himself what Mospheira could have stored; most of all he should have rememberedthe stockpile question that atevi themselves had asked him in what his foundering mind had catalogued as some totally unrelated event.

Damn it to bloody hell, he'd danced into it blindly surehe had a good gift to give in that paper. And it had probably nailed the lid on the coffin, so far as Ilisidi's confidence he wasn't stupidly playing the same game her associates had accused humans of playing for centuries: undermining atevi belief, atevi institutions, all at the same time reserving supplies and fostering an atevi manufacturing program not for atevi's sake but only to get those supplies they needed for themselves.

For a ship maybe some humans had believed more strongly than others was going to return.

His eyes hurt. He pinched his nose. And the arm hurt, lying inert in his lap, perhaps objecting to two-handed keyboard work, perhaps objecting to how he'd slept on it – he'd no idea, but it ached.

From frenetic, the place had grown too quiet. He wanted company. But Banichi and Jago were off about various business, Tabini was probably dealing with the matter he'd dropped in Tabini's lap, Tabini was probably too angry to speak to him, or even preparing orders for his arrest, as he'd invited, who knew?

The very changes he'd taken office to moderate and conduct slowly and without damage were all let loose from Pandora's fabled box, without review, without committee approval, without advice – just fling open the lid and stand back, maybe with one final choice of intervening to try to moderate the effects —

But that choice, even to make it now, entailed human values, human decisions, human ethics; or, perhaps the wiser course – to stand back until atevi action made it clear what was likely to result from atevi values, atevi decisions, atevi ethics – and then decide again whether to interpose human wisdom, at least as the older of two species experiences, the one of the two species who'd been down the technological path far enough to see the flex and flux of their own cultural responses to the dawning of awareness of the universe. Human beings had surely had certain investments in their planetary boundaries, once upon a time. Humans had had to realize the sun was a star among other stars. The paidhi didn't happen to know with any great accuracy how humans had reacted to that knowledge, but he'd a troubled suspicion it could have set certain human beliefs on end.

Though that they couldn't work the numbers out exactly wouldn't have broken up associations, re-sorted personal loyalties, cast into doubt a way of looking at the universe – had it?

For all he knew, the way atevi handled the universe was hardwired into atevi brains, and that was what he was playing games with.

He didn't want to think about that.

He got up and wandered finally as far as the library, and took down delicate watercolored books of horticulture, one after the other, to find whether he knew the names.

Of a book of water plants he was mostly ignorant. It was stupid, in the midst of such desperate events, to go back to his computer and enter words, but he was incapable of more esoteric operations.

Saidin came in to ask whether the paidhi would care for supper in, and whether the paidhi's personal staff would eat at the same time or at some later time.

The paidhi didn't know. The paidhi's staff didn't fill him in. He didn't know whether he'd be here for supper or whether he'd be hauled off to confinement.

But that wasn't Saidin's question.

"I can only hope your surmise is more effective than mine," he said. "Nand' Saidin, I have not been a regular or prompt guest. I apologize for myself and my staff."

"Nandi," Saidin said with a bow, "you are no trouble. Do you admire water gardens?"

The book. Of course. "I find the book beautifully drawn."

"I think so. Have you seen the Terraces?"

"On the Saisuran?" The book held a major number of plates of water plants, delicately rendered in pastel tones. "No, I fear the paidhi has very few chances. Malguri was an unusual excursion."

"If you have the chance, nand' paidhi, I recommend them. They're quite near Isgrai'the. Which is very popular."

He was intrigued – by the idea of the famous water gardens, and the Preservation Reserve at Isgrai'the. By the notion he might someday have such a chance.

But most of all he was intrigued by madam Saidin's unprecedented personal conversation. The book, almost certainly a favorite. One was glad to discover a mutual, noncontroversial interest in a subject; a source of ordinary, mundane conversation.

She'd felt the tension in the house and in the guest – and the protector of the house had followed her inquisitorial duty, perhaps; or just – counting that word of doings in the house hadonce found their way to Ilisidi —

He was too damn critical. Too damn suspicious. Wilson's fate beckoned: the man who never laughed, never smiled.

"Nand' Saidin, thank you. Thankyou for recommending Saisuran. I'll hope for it, that I will be able to see it. I'd like that. I truly would."

"One hopes for you, also, nand' paidhi," Saidin said, and left the room, with the paidhi wondering where that had come from, or what Saidin had really meant, what she'd heard from what source inside Tabini's apartments – or whether he'd simply presented her a dejected picture, sitting there staring at the curtains, so morose that the provider of hospitality had simply done her duty for the lady who wanted her guest taken care of.

He knew the mental maze he'd wandered into, wild swings between atevi and human feeling, making only half-translations of concepts in that strange doppelganger language his brain began to contrive in his unprecedented back-and-forth translation, in his real-time listening to one language and rendering it into the other, no time for refinement, no time for precision – leaping desperately from slippery stone to slippery stone, to borrow the image of the book open on the footstool – the water flowers, the stones, half obscured in sun on water —

A visitor would be very foolish to try that pictured crossing. He knew the treachery of it, from Mospheiran streams – which Saidin, in their crazed, divided world, couldn't visit, either.

There was a place like that once and long ago – a stream set well off the road most took up from a remembered highway, a dirt road he'd hiked up from the ranger station, stones over which water lapped in summertime —

But if one went far, far from that pool, farther up, they'd said in a youngster's hearing, a waterfall poured from high up the side of the mountain. One couldn't hear anything but thundering water from the foot of that waterfall, one just stood there, feeling the mist, enveloped by blowing curtains of it —

Wind-borne, the gray sky above him, and the wind racing off the height: the gale-force winds bent down the trees and swept down deluges on the young and very foolish hiker. He'd been soaked to the skin. He'd had to walk down toward that ranger station to keep from freezing.

There were so, so many half-thought experiences that had brought him to what he was, where he was. He remembered walking long after he thought his knees couldn't stop shaking. He'd known he'd been stupid. He'd known he could freeze to death – at least he'd known that people did, in the mountains; but twelve-year-old boys didn't – he wouldn't, he couldn't, it didn't happen to him.

In fact it hadn't. A ranger had come out looking for him on that trail and brought an insulated poncho. The ranger had said he was a stupid kid and he ought to know better.

Yes, sir, he'd said meekly enough, and he'd known then that even if he might have made it, he'd come close to not making it, and he was aware hiking up there with no glance at the sky hadn't been the smartest act of his life.

But he'd never forgotten, either, the storm sweeping sheets of water off the top of the falls. He'd never forgotten being part of the water, the storm, the sound and the elements up there. He'd felt something he knew he'd never forget. He'd wondered on that shaky-kneed, aching way down if the ranger ever had.

And by the time they'd gotten to the ranger station he'd begun to think, by reason of things the man said, that maybe the ranger had gone up there more than once, but stupid kids up from the tourist camp weren't supposed to have that experience: stupid kids from the tourist camp were what the rangers were up there to protect the wildlife and the falls from. So he'd been embarrassed, then, and understood why the rangers were upset with him, and he'd said he was sorry.

The rangers at the station had phoned his mother, fed him, got him warm, and he'd told the man who drove him down the mountain that he'd like maybe to be a ranger himself someday.

And he'd said that he was sorry they'd had to go out looking for him.

The ranger had confided in him he didn't mind the hike up. That he'd hike up the trail in blizzards and icestorms himself to take photographs.

Then for the rest of the trip the man had told him about what gear you really needed to survive up there, and how if he happened by when he was older, he should come up and see about the summer program the rangers had.

In the way of such things, his mother hadn't let him repeat his escapade. She'd chosen the north slopes of Mt. Allen Thomas the next season, probably to keep him from such hikes, and he and Toby both had taken up siding, to the further detriment of his knees, Toby's elbow, and the integrity of their adolescent skulls.

Saidin said – he should see this place. Atevi appreciated such sights. Atevi found themselves moved by such things. There was something, something, at least, that touched a spot in two species' hearts, or minds, or whatever stimulus it took to take a deep breath and feel – whatever two species felt in such places that transcended – whatever two species found to fight about.

He felt less abraded and confused, at least, in the memory-bath. He regretted lost chances – messages unsent: he wondered what Mospheira would think if he asked the international operators to patch him through to the ranger station above Mt. Allen Thomas Resort.

He imagined what contortions the spies on both sides of the strait would go through trying to figure out that code. It all but tempted him.

But he lived his life nowadays just hoping that things he remembered were intact, unchanged, still viable in a rapidly evolving world. He tried to reckon what the man's age had been. He couldn't remember the man's name. The paidhi – with all his trained memory – couldn't recall the man's name.

More, he was afraid to learn the man might have left, or died. He lived all his life somewhere else – afraid to know something he'd left, if he tried to access it, might have changed – or died.

And that particular cowardice was his defense against all that could get to him.

God, what a morass of reasoning. Sometimes —

Sometimes he was such a construction of his own carefully constructed censorships and restraints he didn't know whether there any longer was a creature named Bren Cameron, or whether what he chose to let bubble to the reflective surface of his past defined the modern man, and the rest of him was safely drowned under that shiny surface that swallowed childhood ambitions, childhood dreams, childhood so-called friends – about whom he didn't like to think —

Was thatthe origin of his capacity to turn off that human function and look for something else?