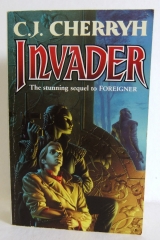

Текст книги "Invader"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Banichi thought that was funny, and sat down and stretched his legs out on a footstool.

"Sit down," Banichi said. "Enjoy the rest."

He did. He sat down, and without clearly realizing how tired he was, nodded off in the chair. And finally gave way to sleep altogether, a comfortable nap, with Banichi close by him.

"He's quite tired," Banichi said to someone quietly. "Keep the noise down."

People were walking nearby, a lot of people, and the paidhi finally had to pay attention to it. He heard Banichi talking to someone, and rubbed the soreness in his neck, blinked the room into focus and realized by the preparations and the conversations that Tabini was coming in, and with him, he was sure, Tano and Algini. Commotion preceded the aiji like a storm front: running through the sitting room and the kitchens, armed security headed through back halls of Taiben where the discreetly camouflaged rail station had its outlet on the side of the building, a station blasted out of the living stone of the hillside. Tano and Algini in fact came in, carrying their own baggage and a couple of heavy canvas cases that looked to hold electronics.

And if the place had felt homelike in his arrival, it felt far other than that now, with weapons in plain sight, Tabini's personal security with armored vests and heavy rifles – Tano and Algini in similar dress and no longer occupied with the ordinary business of clericals and offices: that was surveillance or communications equipment, he was certain.

If Saidin had – and he was sure that she had – put an Atigeini Guild member in the staff – it wasn't such an obvious presence; it was one of the quietly efficient women in soft, expensive fabrics and soundless soles, who whispered when they spoke among themselves and who had such a hair's breadth sensitivity to a design out of adjustment.

Damiri's. Or even Tatiseigi's.

While Damiri was, he recalled with a jolt, still in the Bu-javid – wasn't she?

In the Bu-javid, where herlife might not be secure if an Atigeini moved against Tabini at Taiben. Atevi didn't take hostages, as such. But you damned well knew when you were in reach, and Damiri was – evidently voluntarily – staying in reach.

So very much went on tacit and unspoken – and the paidhiin one and all had had so little idea until he'd had the crash course at Malguri, and finally, rammed through a stupid human head on the plane, the implications he'd missed by not knowing well enough where the associa-tional lines lay, the sub-associations the paidhiin had always known were there, the potency of which the paidhiin had completely underestimated.

The paidhiin had learned to appreciate atevi television, and machimi plays, in which, so often as to be cliche, the stinger in the situation was atevi not knowing an ally had a more complicated hierarchy of man'chithan even the lord had thought he had. Or the lord, who theoretically lacked man 'chiby reason of being a lord, turning out to have man'chito someone no one accounted for.

God, it was right out there in front of the paidhi; it had been right there in front of the State Department and the FO and the university, if anybody had known remotely how to trace it: the university kept meticulous records of genealogies, the provable indications of man'chi– and he knew who was related to whom, more or less. But that didn't say a thing about what Banichi had talked about, the man 'chiof where mates came from – or why.

Or the man'chiof servants; or the man'chione atevi awarded another – Cenedi had found it necessary to tell him, perhaps as a point of honor he'd pay any deserving person, perhaps just a warning for the dim-witted human, that he couldn't regard any debt of life and limb ahead of his man'chito Ilisidi. Cenedi hadn't needed to say that: he'd understood when he'd put Cenedi in a position humans would call debt that Cenedi would owe him no favors.

Banichi had protested vehemently his announcement he'd attached man'chito him and Jago. He didn't know why they should object – unless —

– of course. He felt his face go hot. Banichi had said, with some bewilderment and force – you're not physically attracted to me, and then added that about Jago. Man'chiwas hierarchical. Except the exception Banichi had hinted at. He'd declared man'chieither reversing the order of hierarchy, the paidhi toward his security —

– or he'd said something exceptionally embarrassing to Banichi, who couldn't even, in what Banichi might know about the incident between him and Jago, entirely swear that that wasn't exactly what a crazy human wasfeeling at the moment —

And the university didn't, couldn't, without more shrewd observations from the paidhiin than they'd ever gotten, trace the hidden lines of obligation, the not-so-obvious lines that evidently came down through generations that couldbe inherited, but that weren't, universally; or that could be acquired through physical or psychological attraction; or that could be forged behind closed doors by alliance of two leaders way up in the ranks of the nobility, and bind or not bind their kinsmen, their followers, their political adherents, according to rules he stilldidn't understand and atevi didn't acknowledge, at least out loud, maybe even in the privacy of their own self-realizations. There might be atevi who really, just like humans, didn't wholly understand the psychological entanglements they'd landed in. For a human, he thought, he was doing remarkably well at figuring out the entanglements of man'chiafter the fact; he'd yet to get ahead of atevi maneuvering – and he'd no assurance even now he was looking in the right direction. He'd asked Jago once where her man'chilay – and Jago'd taken at least nominal offense and told him in so many words to mind his own business: it wasn't something polite people ever asked each other. Banichi likewise.

He wondered if even the recipients of such man 'chialways knew what was due them, or if that was, among the other logical and perhaps embarrassing causes, also why Banicbi had turned his declaration away with, Not to as, nand' paidhi – in, for Banichi, quite an expression of dismay.

Servants made a last frantic pass about the sitting room, whisking the suspicion of dust off the fireplace stones, tidying the position of a vase so the largest flowers were foremost.

None of which Tabini gave a glance to when he came in – just a brightening of expression, and, "Ah, Bren-ji, I thought you might be resting. Any difficulties?"

"No, aiji-ma, none, absolutely an easy flight."

"Sit down, sit down —" Tabini sat, flung his feet onto a footstool, and glancing at Naidiri said, not so happily, "See to it, Naidi."

One thought it might be time to get out of Tabini's way and retreat to one's room. But Tabini seemed to have disposed of the matter and proposed a round of dice, which, unlike darts, at least evened the odds for a human participant; and named low stakes, pennies on the point, anda glass of something safely potable for the paidhi, on peril of the purveyor's life.

The purveyor being Banichi, the paidhi had no concern at all. And after that it was himself and Tabini and elderly Eidi, and two of the servants, on order of the aiji, the ladies protesting they couldn't, daren't sit with the aiji, and Tabini saying they'd damn well – they needed a five and security was busy.

So they sat, two gentlemen and a pair of nervous young ladies afraid they'd be beyond their betting limit – they sipped appropriate fruit liqueurs, the ladies as well – they bet pennies, and Tabini and he both lost to one of the maids; Tabini because he was distracted in other thoughts, Bren judged, himself because math counted at least a little in the game of revenge they were playing.

"We're up against a counter," Tabini said, to him and to Eidi. "And these ladies have made common cause."

"And you have a human for a handicap. We should rearrange the alliances."

"Never," Tabini said.

Which lost them, collectively, for an hour and a half, twenty and seven, and a bottle of fruit wine.

And he had a fair idea, by the looks that passed between Tabini and the truly lucky gambler of the pair, that Tabini very well knew Saidin's proxy on the staff, and perhaps more than one of them.

It didn't help the paidhi's anxiety about the peace of the evening at all. But the serving staff was on notice, Tabini, who was very prone to notice the ladies in any gathering, was an absolute gentleman, possibly because it was Damiri's staff, and there was no hint that anything at all was different from previous, all-male visits to Taiben – Tabini might have done as in the past, and had only his own security about them; and didn't – which had Damiri's name all over the situation.

Possibly the aiji didn't want to signal distrust of Damiri. Perhaps the aiji wanted to use the paidhi and himself for bait to draw some action from Tatiseigi, who was, as Banichi and Jago had advised him, an easy train ride away.

Not mentioning overland transport, which the rangers certainly had, and which one could well assume the Atigeini estate had.

Tabini at last leaned comfortably in his chair, one arm draped over the chairback, and waved a hand at the table. "The playing field is yours, dajiin. The bottle. The coin. – The honors. Kindly report us well to your house."

"Aiji-ma." There was a profound bow, profound confusion from one as she rose from the table. A smile from the other that could be challenge, could be acknowledgment – the young woman was surrounded by Guild seniors, against which she wouldn't have a chance for her own survival if she even looked like making a move, and she had to know that.

There was no Filing. Which meant blame and consequences flying straight to the Atigeini head of house, which she had to know also.

Bren drew in his breath and found immediate preoccupation with the position of his glass on the table.

"Pretty," was Tabini's comment after they'd withdrawn with the prizes. "Very sharp. The one on the left is Guild. Did you know?"

He looked up. It wasn't the one he'd thought. "I guessed wrong," he said, chagrined.

"I'm not sure of the other one, either," Tabini said. "Certain things even Naidiri won't say. Damiri herself professes not to be sure. But one suspects it's a pair. I understand you'd no idea of Saidin's position."

He didn't breathe but what Tabini had a report of it.

"I'm completely embarrassed. No, aiji-ma. I hadn't."

"Retired, actually," Tabini said, "but an estimable force. If I can trust Naidiri's estimate – and I wouldn't be living with the lovely lady sharing my bed if I hadn't certain assurances passed through the Guild – she answers primarily to Damiri. Only to Damiri, in point of fact."

There were cliffs and precipices in such topics. He drew a breath and went ahead. "What of Damiri? Are you safe, personally safe, aiji-ma? I'm worried for your welfare."

"I take good care," Tabini said, and turned altogether sideways, one long leg folded against the chair arm, booted ankle on the other knee. "Concerned on behalf of the Association, Bren-ji? Or your directives from Mospheira?"

"To hell with Mospheira," he muttered, and got Tabini's attention. "Aiji-ma, I've quite well damned myself, so far as certain elements of my government are concerned."

"I take it that the message was Hanks, that it said unpleasant things, and that it was not under duress."

"It was accusatory of me, of you, as instituting a seizure of others' rights —" He was aware, as he said it, that he placed Hanks in direct danger, if Tabini were even remotely inclined to retaliatory strikes – and that, in atevi politics, Tabini might no longer have the luxury of tolerating Hanks' actions. "I apologize profoundly, aiji-ma – they're my mistakes. I spend my life trying to figure what atevi will do; I misread her. Of my own species. I have no excuse to offer. I'll give you a transcript."

Tabini waved a hand. "At your leisure. Knowing the company she's keeping enables one rather well to know the content."

"Banichi and Jago seemed to have a very good idea of the content."

"She accuses you to your government."

"Yes."

"Will this be taken seriously?"

"It – will be raised officially, I'm fairly sure. Depending on what goes on inthe government, I will or won't be able to go back to Mospheira."

"Without being arrested?"

"Possibly. That Hanks hasn't gotten a recall order – I fear indicates she still has backing."

Tabini said, "May I speak personally?"

"Yes," he said – one could hardly refuse the aiji whatever he wanted to say, and he hoped it entailed no worse mistake than Hanks

"I hear that your fiancee," Tabini said, "has reneged on her agreement."

"With me?"

"With you. I know of no other."

"There wasn't – actually a clear understanding." He'd talked about Barb with Tabini before. They'd discussed physical attractiveness and the concept of romantic love versus – mainaigi, which rather well answered to a young ateva's hormonal foolishness. "No fault on her part. She'd tried, evidently, to discuss it with me. Couldn't catch me on Mospheira long enough."

"Political pressure?" Tabini asked, frowning.

"Personal pressure, perhaps."

"One suggested before… this woman had more virtue."

He'd made claims for Barb, once upon a while. Praised her good sense, her loyalty. A lot of things he'd said to Tabini, when he'd thought better of Barb.

And if he were honest, probably that weeks-ago judgment was more rational and more on target than the one he'd used last night.

"She's stayed by me through a lot," he said. "I suppose —"

Tabini was quiet, waiting. And sometimes translation between the languages required more honesty than he found comfortable: without it, one could wander deep into definitional traps – sound like a fool… or a scoundrel.

"Did political enemies affect this decision?" Tabini asked.

"Certainly my job did. The absences. The – likelihood of further absences. Just the uncertainty."

"Of safety?"

He hesitated to get into that. Finally nodded. "There've been phone calls."

"She has, as you've said, no security?"

"No. It's not – not ordinary."

"Nor prospect of obtaining it."

"No, aiji-ma. Ordinary citizens just – don't. There's the police. But these people are hard to catch."

"A problem also for your relatives."

He had a suspicion about the integrity of his messages. And the pretense that no atevi understood the language well enough, a pretense which was wearing thinner and thinner.

"There is —" Tabini moved his foot, swung his leg over the arm of the chair. "There is the Treaty provision. We've broken it to keep Hanks here. Would Barb-daja consent to break with this new marriage and join you in residence on the mainland?"

He didn't know what to say for a moment – thought of havingBarb with him, and couldn't imagine —

"It seems," Tabini said, "that there is difficulty for your whole household, on Mospheira, which has perhaps inspired this defection. In her lack of official support, one can, perhaps, see Barb-daja's difficulty."

Or perhaps Banichi or Jago had told him a certain amount. It proved nothing absolutely. He hadtalked to Jago. He'd even talked to Ilisidi.

"This is a security risk," Tabini said. "You should not have to abide threats to your household, if a visa or two would relieve their anxiety – and yours. They would be safe here, your relatives, your wife – if you chose to have this."

His heart had gone thump, and seemed to skip a beat, and picked up again while the brain was trying to work and tell him they'd been talking about Hanks, and accusations, and Hanks' fate, and it could signal a decided chill in atevi-human relations – which he had to prevent. Somehow. "Aiji-ma, it's – a very generous gesture." But to save his life – or theirs – he couldn't see it happening – couldn't imagine his mother and Toby and Jill and the —

No. Not them. Barb. Barb might think she wanted to. Barb might even try – there was a side to Barb that wasn't afraid of mountains. He could remember that now: Barb in the snow, Barb in the sunglare… Barb outside the reality of her job, his job, the Department, the independence she had fought out for herself that didn't need a steady presence, just not some damned lunatic isolationist agitator ringing her phone in the dead of night.

"My relatives – wouldn't – couldn't – adapt here. They'd be more tolerant of the threats. – Barb…"

He couldn't say no for her. She had no special protection, no more than his family. But she couldadapt. It was – in a society she'd not feel at home in – a constant taste of the life she'd seemed to love: the parties, the fancy clothes, the glittering halls. Barb would, give her that, try to speak the language. Barb would break her neck to learn it if it got her farther up the social scale, not just the paidhi's woman, but Barb-daja; God – she'd grab it on a bet. Until she figured out it was real, and had demands and limitations of behavior.

Stay with at that point was another question. Adapt to it, was a very serious question. He didn't think so, not in the long term.

More, he didn't want to sleep with her again. It had become a settled issue, Barb's self-interest, Barb's steel-edged self-protection: the very quality that had made her his safe refuge raised very serious questions, with Barb brought into the diplomatic interface, under the stress the life necessarily imposed —

And the constant security. And the fact – they needed each other more than they loved each other. Or loved anyone at all, any longer. They'd damaged each other. Badly.

"So?" Tabini asked him.

"Barb is a question," he said. "Let me think about it, aiji-ma, with my profound gratitude."

"And your household, not?"

"My mother —" He'd spoken to Tabini only in respectful terms of his mother. Of Toby. "She's very human. She's very temperous."

"Ill-omened gods, Bren, I have grandmother. They could amuse each other for hours!"

He had to laugh. "A disaster, aiji-ma. I fear – a disaster. And my brother – if he couldn't have his Friday golf game, I think he'd pine and die."

"Golf." Tabini made a circular motion of the hand. "The game with the little ball."

"Exactly so."

"This is a passion?"

"One gambleson it."

"Ah." To an atevi that explained everything – and restored Tabini's estimate of Toby's sanity.

"My relatives are as they are. Barb – I'll have to think. I fear my mind right now is on the ship. And the business last night. And Hanks-paidhi."

"Forget Hanks-paidhi."

That was ominous. And he resolutely shut his mouth. Protest had already cost two lives.

"I trust," Tabini said then – but Naidiri came in, bowed despite Tabini's casual attitude, and presented a small message roll, at which Tabini groaned.

"It came with a cylinder," Naidiri said. "Considering the source, we decided security was better than formality."

"I certainly prefer it." Tabini opened it and read it. "Ah. Nand' paidhi. Geigi sends his profound respect of your person and assures you his mathematicians find great interest in the proposed solution to the paradox, which they believe to have far-reaching significance. He is distraught and dismayed that his flowers were rejected at the airport, which he believes was due to your justified offense at his doubt. He wishes to travel to Taiben in person to present his respect and regret. The man is determined, nadi."

"What shall I answer this man?" Bren asked. "This is beyond my experience, aiji-ma."

"Say that you take his well-wishes as a desirable foundation for good relations and that you look forward personally to hearing his interpretation of the formulae and the science as soon as you've returned to the capital. Naidi-ji, phrase some such thing. Answer in the paidhi's name before this man buys up all the florists in Shejidan. – You've quite terrified the man, Bren-ji. And quite – quite uncharacteristically so. Geigi is not a timorous man. He's sent me very passionate letters opposing my intentions. What in all reason did you say to him?"

"I don't know, aiji-ma. I never, never wished to alarm him."

"Power. Like it or not." Tabini gave back the message roll, and Naidiri went back, one presumed, to the little staff office Taiben had in the back hall. "On my guess, the man doesn't understand why you went personally to the observatory. He doesn't understand the signal you sent – weknow your impulsive character. But lord Geigi – is completely at a loss."

"I couldn't rely on someone to translate mathematics to me when so much was riding on it. Third-hand never helps on something I can hardly understand myself. – Besides, it was nand' Grigiji's work. Banichi said he baffles his own students."

"That he does," Tabini said. "I've asked what we should do for this man. He professed himself content, and took a nap."

"Did he?"

"The emeritus' students, however, begged the paidhi to give them a chance to write to the university on Mospheira."

Bren drew in a breath and let it go slowly. "Very deep water."

"One believes so."

"Access to atevi computer theory discussions? The university would be interested. It might move the cursed committee."

"Possibly."

He couldn't help it, then. He gave a quiet, rueful laugh. "If Mospheira's speaking to me. I've yet to prove that. And the ship – will change a lot of things."

"Ah. No challenge even for my 'possibly.' So sad."

"I will challenge it. But I won't tell you how in advance, aiji-ma. Leave me my maneuvering room."

Tabini laughed silently. "So. You and I were to go fishing. But I fear there's a business afoot —"

He didn't know how he could drag himself out of the chair. Or, in fact, sleep at night. "One understood back in Shejidan, aiji-ma, that the fish might have to wait."

"You look very tired."

"I can look more enthusiastic. Tell me where and when. Otherwise I'll save it for the landing."

"I think we should have a quiet supper, the two of us. We should talk about the character of our women, share a game of darts, and drink by the fire."

"That sounds like a very good program, aiji-ma."

"The fish can sleep safely this evening, then. Possibly the paidhi will get some rest."

"The paidhi certainly intends to try."

It was, as Tabini promised, a quiet supper. Other people were very busy – Banichi and Jago had gone off duty for the last quarter of the afternoon and, one assumed, fallen facedown and slept like stones, Bren told himself: it had to be rare that they could sleep in the sure knowledge they were absolutely safe, absolutely surrounded by security, and the primary job wasn't theirs.

He certainly didn't begrudge them that.

And after supper, Tabini defeated him soundly at darts – but he won three games of ten, whether by skill or the aiji's courtesy, and they sat, as Tabini had promised, by the fire.

"I'd imagine our visitors are well away by now," Bren said in the contemplation the moment offered. "I'd imagine they'll board the lander at the very last – ride out in whatever craft will take them to the brink, and perform their last-minute checks tomorrow. Everything has to be on schedule, or I'm sure they'd have called."

"These are very brave people," Tabini said.

"Very scared people. It's a very old lander." He took a sip of liquor and stared into the endless patterns of the wood fire. "The world's changing, aiji-ma. Mine is, the mainland will." Tabini had never yet mentioned Ilisidi's presence in the house. "I have a request, aiji-ma, that regard for me should never prompt you to grant against your better judgment. They tell me the dowager was here last night. That she's with the Atigeini. – Which I do not understand. But I would urge —"

Tabini was utterly quiet for the moment. Not looking at him. And he looked back toward the fire.

"In my perhaps mistaken judgment, aiji-ma – the dowager, if she is involved, seems more the partisan of the Preservation Commission than of any political faction. At least regarding ideas expressed to me. Perhaps she was behind the events last night. But I don't think so."

"You don't think so."

"I think if Cenedi had meant to do me harm, he had far subtler means. And they wouldn't guest with the Atigeini if they'd shot up the breakfast room. That's all I'll say this evening on politics. But I want to speak for the dowager, if I have any credit at all."

"Your last candidate for favor was Hanks-paidhi."

"True."

"Well, trust grandmother to find a landing spot. I offered her a plane. Which she declined."

"It's, as I said, Tabini-ma, the limit of my knowledge. I only wish to communicate my impression that she viewed the experience of atevi before humans came as an important legacy to guide the aiji in an age of change and foreign ways. I realize I'm a very poor spokesman for that viewpoint. But even against your displeasure I advance it, as my minimal debt to what I believe to be a wise and farseeing woman."

"Gods inferior and blasphemed, you're so much more collected than Brominandi. That wretch had the effrontery to send me a telegram in support of the rebels, do you know?"

"I hadn't known."

"He should take lessons from you. At telegraph rates he's spent his annual budget."

"But I believe it, aiji-ma. I'd never urge you against what I believe is to the benefit of atevi."

"Grandmother will take no harm of me."

"But Malguri."

"Nor will there be public markets at Malguri. – Which some would urge, you understand. Some see the old places as superfluous, an emblem of opprobrious privilege."

"I see it," he said, "as something atevi can never obtain from human books."

Tabini said nothing in reply to that. Only recrossed his ankles on the footstool, and the two of them stared at the fire a moment.

"Where is man'chi," Tabini asked him, "paidhi-ji?"

"Mine? One thought atevi didn't ask one another such questions."

"An aiji may ask. – Of course —"

A hurried group of security went through the room, and the seniormost, it seemed, stopped. "Aiji-ma, pardon." The man gave Tabini a piece of paper, which Tabini read.

Tabini's leg came down off the chair arm. Tabini sat up, frowning.

"Is it distributed?" Tabini asked.

"Unfortunately so."

"No action against the paper. Do inquire their connections. One wonders if this is accidental."

"Aiji-ma." The security officer left.

And Tabini scowled.

"Trouble?" Superfluous question.

"Oh, a small matter. Merely a notice in the resort society paper that we're here forthe landing."

"Lake society?"

"The lake resort. A thousand tourists. At least. Passed out free to every campsite at the supply store."

"God."

"Invite the whole damned resort, why don't we? They'll be here, with camping gear and cameras andchildren! We've a chance of heavy arms fire! Of bombs, from small aircraft! We've a thousand damned tourists, gods unfortunate!"

Public land. There was no border, no boundary. One thing ran into the other.

" Damnedif this is a mistake," Tabini said. "The publisher knows it's stupid, the publisher knows it won't make a landing easier or safer. Dammit, dammit, dammit!"

Tabini flung himself to his feet. Bren gathered himself up more cautiously, as Tabini drew his coat closed and showed every sign of taking off.

"We can't be butchering tourists in mantraps," Tabini said. "Bren, put yourself to bed. Get some rest. It's clear I won't."

"If I could help in any way —"

"Since none of our problems of tonight speak Mosphei', I fear not. Stay by the phone. Be here in case we receive calls from the heavens that something's gone amiss. Don't wait up."

Property where private was sacrosanct and even tourists respected a security line – but a landing was a world-shattering event. The Landing was the end of the old world as the Treaty was the beginning of the new. Atevi were attracted to momentous events, and believed, in the way of numbers, that having been in the harmony of the moment gave them a special importance in the universe.

There couldn't be an ateva in the whole world, once the news got beyond Taiben and once it hit the lake resort and the airport, who wouldn't phone a relative to say that humans were falling out of the sky again, and they were doing it here, at dawn tomorrow.

It wasn't a prescription for early sleep. Tano and Algini came in briefly to say they'd indeed contacted the rangers, who took the rail over to the lake and personally, on the loudspeakers, advised tourists that it was a dangerous area, that and that they risked the aiji's extreme displeasure.

"One wonders how many have already left," Bren said.

"The rangers are all advised," Algini said.

"But one couldn't tell tourists from Guild members looking for trouble."

"Many of us know each other," Tano said. "Especially in the central region."

"But true," Algini said, "that one has to approach closer than one would like to tell the difference. It's very clever, what they've done."

"Who's done? Does anybody know who's behind this?"

"There's a fairly long list, including neighboring estates."

"But the message. Was it the dowager's doing?"

"One doesn't know. If —"

"Nand' paidhi," a member of Tabini's staff was in the doorway. "A human is calling."

"I'm coming." He was instantly out of the chair, and with Tano and Algini who had come from that wing, which they'd devoted to operations, he followed the man to the nearest phone.

"This is Bren Cameron. Hello?"

" Jase Graham. Got a real small window here. Closer we get…" There was breakup. " Everything on schedule?"

"We're fine. How are you?"

"I lost that. Where are you?"

"Fifty kilometers from the landing site. I'll bethere, do you hear?"

"We're… board the lander. Systems… can you…?"

"Repeat, please."

There was just static. Then: " See you. You copy?"

"Yes! I get that! I'll be there!"

The communication faded out in static, tantalizing in what he didn't know, reassuring in what he could hear.

And what could they say? Watch out for hikers? We hope nobody shoots at the lander?

"They're on schedule," he said. "When are we going out there?"

"One hasn't heard that you were going, nand' paidhi," Tano said.

That was a possibility he hadn't even considered. If he was at Taiben, he'd damn sure be at the landing in the morning. He wasn't leaving two humans to be scared out of their minds or to make some risky misassumption before they reached the lodge.