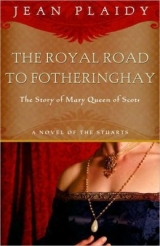

Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

FIVE

THE QUEEN OF FRANCE! THE FIRST LADY IN THE LAND! SHE was second only to the King, and the King was her devoted slave. Yet when she remembered that this had come about through the death of the man whom she had come to regard as her beloved father, she felt that she would gladly relinquish all her new honors to have him back.

François was full of sorrow. He had gained nothing but his father’s responsibilities, and dearly he had loved that father. So many eyes watched him now. He was under continual and critical survey. Terrifying people surrounded him and, although he was King of France, he felt powerless to escape from them. Those two men who called themselves his affectionate uncles held him in their grip. It seemed to him that they were always present. He dreamed of them, and in particular he dreamed of the Cardinal; he had nightmares in which the Cardinal figured, his voice sneering: “Lily-livered timorous girl… masquerading as a man!” Those scornful words haunted him by day and night.

There was one other whom he feared even more. This was his mother. If he were alone at any time she would come with all speed to his apartments and talk with him quietly and earnestly. “My dearest son… my little King… you will need your mother now.” That was the theme of all she said to him.

He felt that he was no better than a bone over which ban dogs were fighting.

His mother had been quick to act. Even during her period of mourning she had managed to shut out those two men. She had said: “The King is my son. He is not a King yet; he is merely a boy who is grieving for his father. I will allow no one to come near him. Who but his mother could comfort him now?”

But her comfort disturbed him more than his grief, and he would agree to anything if only she would go away and leave him alone to weep for his father. Mary could supply all the comfort he needed, and Mary alone.

Mary’s uncles came to the Louvre. They did not ask for an audience with the Queen of France; there could be no ceremonies at such a time, said the Cardinal, between those who were so near and dear. He did not kneel to Mary; he took her in his arms. The gesture indicated not only affection, but mastery.

“My dearest,” he murmured, “so it has come. It has come upon us unexpectedly. So my darling is Queen of France. That is what I and your uncles and your grandmother have always wished for you.”

Mary said with the faintest reproof: “We are as yet mourning the dead King.”

The Cardinal looked sharply at her. Had the great honor gone to her head? Was she, as Queen of France, less inclined to listen to her uncle than she had been as Dauphine?

He would not allow that.

“You will need your family more than ever, Mary.”

“Yes, Uncle, I know. I have often thought of being Queen, and now I think much of the King and how kind he always was and how dearly we children loved him. But he was not kind to everybody. Terrible things happened to those who were not of the true faith, and at his command.”

“Heretics could not be tolerated in this country,” said the Cardinal.

“But, Uncle, I am a good Catholic, yet I feel that it is wrong to torture people … to kill them because they wish to follow a different line of thought. Now that I am Queen I should like to promise everyone religious liberty. I should like to go to the prisons where people are held because of their religious opinions, open the doors and say: ‘Go in peace. Live in peace and worship God in the way you wish.’”

The Cardinal laughed. “Who has been talking to you, my dearest? This is not a matter of religious thought—” He remembered his robes suddenly and added, “Only. Why, these men who lie in prison care little for opinions. They wish to set the Protestant Bourbons on the throne. Religion and politics, Mary, are married to one another. A man meets his death on the Place de Grève, perhaps because he is a heretic, perhaps because he is a menace to a Catholic monarch. The world is divided into Catholics and Huguenots. But you shall learn more about these things. For the time being you will, I am sure, with your usual good sense take the advice of your uncle François and your uncle Charles who think of nothing but your good.”

“It is a comfort to know that you are with me.”

He kissed her hand. “We will make the throne safe for you, dearest, and the first thing we must do is to remove all those who threaten us. Where is François? Take me to him. He must send for the Constable de Montmorency at once. The old man’s day is over. There you will see disappear the greatest of our enemies; and the other…” He laughed. “I think we may trust the Queen-Mother to deal adequately with Madame de Valentinois.”

“The Constable! Diane!” cried Mary. “But—”

“Oh, Diane was charming to you, was she not? You were her dear daughter. Do not be deceived, my dearest. You were her dear daughter because you were to marry the Dauphin, and it was necessary for all the Kings children to be her dear children. She is an enemy of our house.”

“But she is your sister by marriage.”

“Yes, yes, and we do not forget it. But she has had her day. She is sixty and her power has been stripped away from her. When the splinter entered the King’s eye she became of no importance—no more importance than one of your little Marys.”

“But does not love count for something?”

“She did not love you, child. She loved the crown which would one day be yours. You have to grow up, Mary. You have to learn a great deal in a short time. Do not mourn for the fall of Madame de Valentinois. She had her day; she may well be left to that Queen whom she has robbed of dignity and power for so many years.” He smiled briskly. “Now, tell the King that you wish to see him.”

She went to the apartment where François sat in lonely state.

He was glad to see Mary, but wished she had come alone; and particularly he wished that she had not brought the Cardinal with her.

He tried to look as a king should look; he tried to behave as his father had. But how could he? In the presence of this man he could only feel that he was a lily-livered girl masquerading as a king.

“Your Majesty is gracious to receive me,” said the Cardinal, and as he took the King’s hand, noticed that it was trembling.

“My uncle the Cardinal has something to say to you, dearest,” Mary announced.

“Mary,” said François, “stay here. Do not go.”

She smiled at him reassuringly. The Cardinal, signing to them to sit on their chairs of state, stood before them.

“Your Majesty well knows that your enemies abound,” he said. “Your position has changed suddenly and you will forgive me, Sire, if I remind you that you are as yet very young.”

The King moved uneasily in his chair. His eyes sought Mary’s and sent out distress signals.

“There is one,” continued the Cardinal, “whom it will be necessary for Your Majesty to remove from his sphere of influence without delay. I do not need to tell you that I refer to Anne de Montmorency, at present the Constable of France.”

“The… the Constable…,” stammered François, thinking of the old man who alarmed him only slightly less than the sardonic Cardinal himself.

“He is too old for his office, and Your Majesty’s first duty will be to summon him to your presence. Now this is what you will say to him—it is quite simple and it will make the position clear. ‘We are anxious to solace your old age which is no longer fit to endure the toil and hardship of service.’ That is all. He will give up the Seals, and Mary is of the opinion that they should be given to the two men whom you know you can trust. Mary has suggested her uncles, the Duke of Guise and myself.”

“But…,” murmured François, “the Constable!”

“He is an old man. He is not trustworthy, Sire. He has been in the hands of your enemies, a prisoner after Saint Quentin. What plight would France be in now had not my brother hurried to the scene of that disaster? As all France knows, François de Guise saved Your Majesty’s crown and your country from defeat. Mary, your beloved Queen, agrees with me. She wishes to help you in all things. She wishes to spare you some of the immense load of responsibility. That is so, is it not, Mary?”

The caressing hand was pressed warmly on her shoulder. She felt her will merge in his. He was right, of course. He was her beloved uncle who had been her guide and counselor, her spiritual lover, ever since she came to France.

“Yes, François,” she agreed, “I want to help you. It is too big a load for you, because you are not old and experienced. I long to help you, and so does my uncle. He is wise and knows what is best.”

“But, Mary, the Constable? And there is my mother—”

“Your mother, Sire, is wrapped up in her grief. She is a widow mourning her husband. You can understand what that means. She must not be troubled with these matters of state. As yet she could not give her mind to them.”

“You must do as my uncle says, François,” insisted Mary. “He knows. He is wise and you must do as he says.”

François nodded. It must be right; Mary said so; and, in any case, he wished to please Mary whatever happened. He hoped he would remember what to say.

“‘We are anxious to solace your old age…’”

He repeated the words until he was sure he knew them by heart.

MARY KNEW that the carefree days were over. Sometimes, at night, she and François would lie in each other’s arms and talk of their fears.

“I feel as though I am a ball, thrown this way and that,” whispered the King. “All these people who profess to love me do not love me at all. Mary, I am afraid of the Cardinal.”

Mary was loyal, but she too, during the last weeks, had been conscious of a fear of the Cardinal. Yet she would not admit this. She had been too long in his care, too constantly assured of his love and devotion.

“It is because he is so clever,” she said quickly. “His one thought is to serve you and make everything right for us both.”

“Mary, sometimes I think they all hate each other—your uncles, my mother, the King of Navarre…. I think they all are waiting to tear me into pieces and that none of them loves me. I am nothing but a symbol.”

“The Cardinal and the Duke love us both. They love me because I am their niece and you because you are their nephew.”

“They love us because we are King and Queen,” asserted the King soberly. “My mother loves me because I am the King; she loves Charles because, if I die, he will be King; she loves Elisabeth because she is Queen of Spain. Claude she loves scarcely at all, because she is only the wife of the Duke of Lorraine. Margot and Hercule she does not love as yet. They are like wine set aside to mature. Perhaps they may be very good when their time comes, and perhaps no good at all. She will wait until she knows which, before she decides whether or not she loves them.”

“She loves your brother Henri very much,” Mary reminded him. “Yet he could not be King unless you and Charles both die and leave no sons behind you.”

“Everybody—even my mother—must do something sometimes without a reason. So she loves my brother Henri. Mary, how I wish we could go back to Villers-Cotterets and live quietly there. How I wish my father had never died and that we were not King and Queen. Is that a strange wish? So many would give everything they have in order to wear the crown, and I… who have it, would give away all I have—except you—if, by so doing, I could bring my father back.”

“It is your grief, François, that makes you say that. Papa’s death was too sudden.”

“It would be the same if I had known for years that he was going to die. Mary, we are but children, and King and Queen of France. Perhaps if my father had lived another ten or twenty years we should have been wiser… perhaps then we should not have been so frightened. Then I should have snapped my fingers at the Cardinal. I should have said: ‘I wish to greet my uncle, the King of Navarre, as befits his rank. I will take no orders from you, Monsieur le Cardinal. Have a care, sir, or you may find yourself spending the rest of your days in an oubliette in the Conciergerie!’ Oh, Mary, how easy it is to say it now. But when I think of saying it to him face-to-face I tremble. I wish he were not your uncle, Mary. I wish you did not love him so.”

“I wish I did not.” The words had escaped her before she realized she was saying them.

There were items of news which seeped through to her. The persecutions of the Huguenots had not ceased with the death of Henri, but rather had increased. The Cardinal had sworn to the Dukes of Alva and Savoy on the death of Henri that he would purge France of Protestants, not because the religious controversy was of such great importance to him but because he wished to be sure of the support of Philip of Spain for the house of Guise against that of Bourbon. He was eager now to show Philip that he would honor his vow.

This persecution could not be kept from the young King and Queen. The Huguenots were in revolt; there was perpetual murmuring throughout the Court. Never had the prisons been so full. The Cardinal was determined to show the King of Spain that never would that monarch find such allies in France as the Guises.

There was something else which Mary had begun to discover. This uncle who had been so dear to her, who had excited her with his strange affection, who had taught her her duty, who had molded her to his will, was hated—not only by her husband, but by many of the people beyond the Court.

Anagrams were made on the name of Charles de Lorraine throughout the country as well as in the Court. “Hardi larron se cèle,” was murmured by daring men as the Cardinal passed. “Renard lasche le roi!” cried the people in the streets.

Prophecies were rife. “He will not live long, this Cardinal of Lorraine,” said the people. “One day he will tread that path down which he has sent so many.”

Great men, Mary might have told herself, often face great dangers. Yet she could not fail to know that beneath those scarlet robes was a padded suit, a precaution against an assassins dagger or bullet. Moreover the Cardinal had, in a panic, ordered that cloaks should no longer be “worn wide,” and that the big boots in which daggers could be concealed should be considerably reduced so that they could accommodate nothing but the owners feet. Every time Mary noticed the new fashions she was reminded that they had been dictated by a man who dispensed death generously to others while he greatly feared it for himself. It was said that the Guises went in fear of their lives but, while the Duke snapped his fingers at his enemies, the Cardinal was terrified of his.

He is a coward, decided Mary with a shock.

The fabric of romance which she had built up as a child in Scotland and which had been strengthened by her first years in France was beginning to split.

She was vaguely aware of this as she held the boy King tightly in her arms. They were together—two children, the two most important children in France, and they were two desolate lonely ones. On either side of them stood those powerful Princes, the Guises and the Bourbons; and the Valois, represented by Catherine the Queen-Mother, Mary feared more than either Guise or Bourbon.

THE COURT was moving south on its journey toward the borders of France and Spain. With it went the little bride of Philip of Spain, making her last journey through her native land. At each stage of the journey she seemed to grow a little more fearful, a little more wan. Mary, to whom she confided her fears, suffered with her in her deep sympathy.

Francois’s health had taken a turn for the worse. Abscesses had begun to form inside his ear, and as soon as one was dispersed another would appear. Ambrose Paré, who was considered the cleverest doctor in the world, was kept in close attendance.

Mary herself suffered periodic fits of illness, but they passed and left her well again. Her radiant health was gone, but if her beauty had become more fragile it was as pronounced as ever. There was still in her that which the Cardinal had called “promise”; there was still the hint of a passionate depth yet to be plumbed, and this was more appealing than the most radiant beauty, it seemed, for in spite of her impaired health, Mary continued to be the most attractive lady of the Court.

They had traveled down to Chenonceaux, that most beautiful of all French châteaux, built in a valley and seeming to float on the water, protected by alder trees. The river flowing beneath it—for it was built on a bridge—acted as a defensive moat. It had always been a beautiful castle, but Diane had loved it and had employed all the foremost artists in France to add to its beauty. Henri had given it to her although Catherine had greatly desired it; and the Queen-Mother had never forgiven this slight. One of her first acts, on the death of her husband, was to demand the return of Chenonceaux. In exchange, she had been delighted to offer Diane the Château de Chaumont, which Catherine considered to have a spell on it, for she swore that she herself had experienced nothing but bad luck there, and while living in it had been beset by evil visions.

As the royal party—complete with beds and furnishings, fine clothes and all the trappings of state—rode toward Chenonceaux, the Queen-Mother talked to the Queen of the improvements she intended for the château. She would have a new wing, and there should be two galleries—one on either side, so that when she gave a ball the flambeaux would illuminate the dancers from both sides of the ballroom. She would send to her native Italy for statues, for there were no artists in the world to compare with the Italians, as old King François had known; the walls should be hung with the finest tapestries in the world and decorated with the most beautiful of carved marble.

“You are fortunate,” said Mary, “to find something to do which will help you to forget your grief for the late King.”

Catherine sighed deeply. “Ah yes, indeed. I lost that which was more dear to me than all else. Yet I have much left, for I am a mother, and my children’s welfare gives me much to think of.”

“As does this beautiful château, so recently in the possession of Madame de Valentinois.”

“Yes… yes. We must all have our lighter moments, must we not? I hope that Chenonceaux will offer rich entertainments to my son and Your Majesty.”

“You are so thoughtful, Madame.”

“And,” went on the Queen-Mother, “to your children.”

“We are very grateful indeed.”

“I am concerned for my son. Since his marriage he has become weaker. I fear he grows too quickly.” The Queen-Mother leaned from her horse and touched Mary’s hand. She gave her ribald laugh. “I trust you do not tire him.”

“I… tire him!”

Catherine nodded. “He is such a young husband,” she said.

Mary flushed. There was in this woman, as in the Cardinal, the power to create unpleasant pictures. The relationship which she and François knew to be expected of them, and which the Cardinal had made quite clear to them was their duty to pursue, gave them both cause for embarrassment. For neither of them was there pleasure. They could never banish thoughts of the Cardinal and Queen-Mother on such occasions. It seemed to them both that those two were present—the Cardinal watching them, shaking his head with dissatisfaction at their efforts, the Queen-Mother overcome with mirth at their clumsy methods. Such thoughts were no inducement to passion.

“He is so weak now,” said Catherine, “that I am convinced that even if you did find yourself enceinte, no one would believe the child was the King’s.”

Again that laugh. It was unbearable.

They came to Chenonceaux, and Mary’s anger with Catherine had not left her when her women were dressing her for the banquet that night.

She looked at her reflection in the beautiful mirror of Venetian glass—the first which had ever been brought to France—and she saw how brilliant were her long, beautiful eyes. There was always some meaning behind the words of the Queen-Mother. Mary guessed that, for all her laughter, she was very much afraid that Mary was with child. Mary was beginning to understand why. If she had a child and François died, Catherine’s son, Charles, would not be King; and Catherine was longing for the moment when Charles should mount the throne. François had once said: “My mother loves me because I am the King; she loves Charles because, if I die, he will be King.” But although François was King he was ruled by Mary’s uncles, and Catherine wished to reign supreme. That was why she had appointed special tutors for her son Charles. It would seem, thought Mary, in sudden horror, that she wants François to die.

She looked round the beautiful room which was her bedchamber. Perhaps here King Henri and Diane had spent their nights, making love in the carved oak bedstead with its hangings of scarlet satin damask. She glanced at the carved cabinets, the state chair, the stools; and she was suddenly glad that she had not Catherine’s gift for seeing into the future. She was afraid of the future.

“Bring me my gown,” she said to Mary Beaton, who, with Seton, helped her into it. It was of blue velvet and satin decorated with pearls.

“A dress indeed for a Queen,” said Flem, her eyes adoring. “Dearest Majesty, you look more beautiful than ever.”

“But Your Majesty also looks angry,” countered Beaton. “Was it the Queen-Mother?”

“She makes me angry,” admitted Mary. “How like her to come to this château! She says that Chaumont is full of ghosts. I wonder the ghost of the dead King does not come and haunt her here.”

“It is very soon after…,” murmured Livy.

“She’s inhuman!” cried Mary.

One of her pages announced that the Cardinal was come to see her. The ladies left her.

As he kissed her hand, the Cardinal’s eyes gleamed. “Most beautiful!” he declared. “Everyone who sees you must fall in love with you!”

Mary smiled. Her image looked back at her from the Venetian mirror. There was an unusual flush in her cheeks and her eyes still sparkled from the anger Catherine had aroused. She enjoyed being beautiful; she reveled in the flattery and compliments which came her way. Tonight she would dance more gaily than she ever had before, and so banish from her mind the unpleasantness engendered by the Queen-Mother. François had been advised to rest in his bed. It was wrong of her to feel relieved because of this; but nevertheless it was comforting to remember she need not be anxious because he might be getting tired. Tonight she could be young and carefree. She was, after all, only seventeen; and she was born to be gay.

“Those who have always been in love with you,” went on the Cardinal, “find themselves deeper and deeper under your spell. But tell me, is there any news?”

She frowned slightly. “News? What news?”

“The news which all those who love you anxiously wait to hear. Is there any sign of a child?”

Now she was reminded of that which she preferred to forget—François, the lover who could not inspire her with any passion, François, who apologized and explained that it was but their duty. She saw the pictures in her mind reflected in the Cardinal’s eyes. She saw the faint sneer on his lips, which was for François.

“There is no sign of a child,” she said coolly.

“Mary, there must be; there must be soon.”

She looked at the sparkling rings on her delicate fingers and said: “How can you speak to me thus? If God does not wish to bless our union, what can I do about it?”

“You were made to be fruitful,” he said passionately. “François, never!”

“Then how could we get a child?”

His eyes had narrowed. He was trying to make her understand thoughts which were too dangerous to be put into words.

“There must be a child,” he repeated fiercely. “If the King dies, what will your position be?”

“The King is not dead, and if he does die, I shall be his sorrowing widow who was always his faithful wife.”

The Cardinal said no more; he turned away and began to pace the room.

“I am a very happy wife,” said Mary softly. “I have a devoted husband whom I love with all my heart.”

“You will hold Court alone tonight?” said the Cardinal, stopping in his walk to look at her. “You will dance. The most handsome men in the Court will compete for the honor of dancing with you. I’ll warrant Henri de Montmorency will be victorious. Such a gallant young man! I fear his marriage is not a very happy one. Yet doubtless he will find many to comfort him, if comfort he needs.”

He looked into his niece’s eyes and watched the slow flush rise from her neck to her brow. She would not look at the pictures which he was holding before her; she would not let him have possession of her mind. She feared him, almost as much as François feared him, and she was longing now to break away from him.

“Let us go now,” she said. “I will call my women.”

There was a satisfied smile about his lips as he left her. But she would not think of him. She was determined to enjoy the evening. She went to see François before going down to the banqueting hall. He lay on his bed, his eyes adoring her, telling her that she looked more beautiful than ever. He was glad that he could rest quietly in his bed, yet he wished that she could be with him.

She kissed him tenderly and left him.

Down to the great hall she went with her ladies about her.

“The Queen!”

All the great company parted for her and fell to their knees as she passed them.

The Cardinal watched her speculatively. If she were in love, he thought, she would know no restraint; then she would turn from a husband who, if not impotent, was next door to it. Then there would be a child. It would be almost certain with one as passionate as Mary would become. It would not be the first time that a King believed the child of another man to be his.

His eyes met those of the Queen-Mother. She composed her features. Ah, thought the Cardinal, you were a little too late that time, Madame le Serpent. You are desperately afraid that she is already with child. That would spoil your plans, Madame. We know that you are waiting for your son François to die, so that your little puppet Charles, his Mothers boy, shall take the throne, and you, Madame, shall enjoy that position behind it which is now mine and my brothers. But he must not die yet. Everything must be done to prevent such a calamity. He must not die until he has fathered Mary’s child.

Mary sat at the head of the banqueting table and her eyes glistened as she surveyed the delicacies set before her. The Queen-Mother, in her place at the great table, for the moment forgot her anxiety as to the condition of her daughter-in-law. She relished her food even more than did the little Queen. Fish delicacies, meat delicacies, all the arts known to the masters of cookery were there to be enjoyed. They both ate as though ravenous, and the company about them did likewise.

But when the meal was over and Mary rose, she was beset by such pains that she was forced to grip the table for support; the lovely face beneath the headdress of pearls was waxy pale. Mary Beaton ran to her side to catch her before she fell fainting to the floor.

There was consternation, although all were aware of the attacks which now and then overcame the Queen.

The Cardinal was alert. He had never seen Mary swoon before, although he knew that the pains she suffered, particularly after a meal, were often acute. Could it be that she was mistaken when she had said there was not to be a child? He saw the color deepen in his brothers face and the eye above the scar begin to water excessively. Could Mary be unaware of her state? Was it the quickening of the child which had made her faint?

In such a moment the brothers could not hide their elation. The Queen-Mother intercepted their triumphant glances. She also was too moved to mask her feelings. This could be as much her tragedy as the Guise brothers’ triumph.

She quickly pushed her way to the fainting girl.

Mary Beaton said: “I will get Her Majesty’s aqua composite at once, Madame. It never fails to revive her.”

The Queen-Mother knelt down by the Queen and looked searchingly into her face. Mary, slowly opening her eyes, gave a little cry of horror at finding the face of Catherine de Médicis so close to her own.

“All is well, all is well,” said Catherine. “Your Majesty fainted. Have you the aqua? It is the best thing.”

The Queen-Mother herself held the cup to the Queens lips.

“I am better now,” declared Mary. “The pain was so sharp. I … I am afraid it was too much for me.”

They helped her to her feet and she groped for the arm of Mary Beaton.

“I will retire to my apartments,” she said. “I beg of you all, continue with your dancing and games. I shall feel happier if you do.”

The Cardinal stepped forward, but Mary said firmly: “No, my dear Cardinal. I command you to remain. You too, Madame. Come, Beaton, give me your arm. My Marys will conduct me to my chamber and help me to bed.”

They who had crowded all about her drew back and dropped to their knees as, with her four faithful women, she went from the banqueting chamber.

She lay on the oaken bedstead, the scarlet damask curtains drawn about it. The pain had subsided but it had left her exhausted. She would sleep until morning and then rise refreshed from her bed.

She was awakened by a movement at her bedside. She knew that it was not late for she could hear the music from the ballroom. She opened her eyes and, turning, saw the Queen-Mother standing by her bed.

Mary felt suddenly cold with apprehension. “Madame!” she cried, raising herself.

“I did not mean to disturb Your Majesty,” said Catherine. “I came to see if you were at rest.” She laid a hand on Mary’s forehead. “You have a touch of fever, I fear.”

“It is good of you to disturb yourself, Madame, but I know that it will pass. These attacks always do. They are painful while they last, but when they are gone I feel quite well.”

“You have no sickness? You must tell me. Your health is of the utmost importance to me. You know that I have some knowledge of cures. Monsieur Paré will tell you that I come near to being a rival of his. You must let me care for you.”

“I thank you, Madame, but I do not need your care. Where are my women?”