Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

She had known then that her only hope was flight from Scotland, but where could she seek refuge? She must be a fugitive from her own land; her son was lost to her, brought up by her enemies to believe the worst of her; her own brother was determined on her defeat and offered her nothing but a prison or death.

Could she go to France? she had asked herself. She thought of her family there. But France was ruled by an evil woman, a woman who had never shown herself to be Mary’s friend. How could she throw herself on the mercy of Catherine de Médicis?

There was only one to whom she could appeal for mercy—the Queen of England; and so for more than eighteen years she remained the prisoner of Elizabeth. She had asked for hospitality and had been given captivity. And during those years there had been one subject which had always been raised when her name was mentioned: the subject of the Casket Letters.

She often thought of those letters, which had been read by all the important people of England and Scotland; the whole world discussed them. There were some who declared they were the actual letters and poems Mary had written to her lover; others insisted that they were forgeries. If they were authentic, then Mary was exposed as an adulteress and murderess; if they were false, then Mary’s story remained a mystery which none could ever solve. The testament of tortured men could count for little. Such confessions gave satisfaction to none but those who extorted them, and were worthless.

How clear it all became when she looked back on it. Moray, Maitland, Morton—they were the leaders and they were determined to destroy her. They would show her to her subjects as a murderess and adulteress, for only thus could they rouse the people against her.

Those men, who had certainly been more deeply concerned in the murder of her husband than she had, now banded together and self-righteously sought to force her—with Bothwell—to take all the blame. It was necessary to their policy that she and Bothwell should do so; they had sought to write her epitaph for her own generation and all generations to come: Mary Stuart who was involved with her lover in her husband’s murder for the sake of an adulterous passion.

Would they succeed? How could she know? She could only hope that after she was dead there would be those who sought to sift the truth from the lies and at least do her justice.

“Oh God,” she prayed aloud, “have mercy on me. The thief on the cross was forgiven; but I am a greater sinner than he was. Have mercy on me in this hour of my death as You had on him.”

Would her story have been different, she wondered, if Geordie Dalgleish had not produced the silver casket? Would it have been possible for her to return to her country and reign as its Queen, but for those incriminating letters?

Geordie had been arrested when all Bothwell’s servants had been taken up and tortured with the object of making them confess that Bothwell and Mary—and they alone—had been responsible for Darnley’s murder.

Geordie had been Bothwell’s tailor and, as a servant of the Earl, suspect. Perhaps to curry favor with his tormentors he had shown them the silver casket which he said had been found beneath his master’s bed.

Those revealing sonnets were exposed to the world. She had written to her lover of her innermost feelings; and now the whole world was reading what she had written for his eyes alone. She had written letters to her lover, and those letters must have conveyed her great passion for him; but she surely had never written those cruel words, those brutal words, which were said to have been penned while she sat by Darnley’s bedside!

How angry she had been, how shocked, how humiliated! She had wept tears of rage when she had heard that the poems and letters were being publicly read; but now even that seemed of little moment.

In those early days of captivity her hopes had been high. She had been taken from prison to prison—from Carlisle to Bolton, Tutbury, Coventry, Chatsworth, Sheffield, Buxton, Chartley and finally to Fotheringhay.

Buxton held a bittersweet memory for it was at Buxton that the last of her Marys to be with her—Seton—had come near to marriage with Andrew Beaton.

A sad little story theirs had been. Mary Seton had had one great love in her life and that was for her mistress and namesake. Of the four Marys Seton was the one who had loved the Queen best. Andrew Beaton had fallen in love with the quiet and gentle Seton and had spent seven years trying to persuade her to leave her mistress. Mary had watched them and had longed to see her faithful Seton happily married, as she knew she would have been with such a man as Andrew. Why should Seton spend her life in captivity because her mistress must?

Seton made excuses. She would not marry. She had solemnly vowed herself to celibacy. She would never leave her mistress.

But the Queen wished to see the love story brought to a happy conclusion against the grim background of her prison. It had been a pleasant occupation, during the long evenings, to plan for those two.

It was her idea that Andrew should go to Rome to have Seton’s vow nullified. Andrew had left, and what a sad day it had been for her as well as for Seton when the news had come of Andrew’s sickness and death.

So Seton’s vow was not broken and Seton remained with her mistress seven years after the death of Andrew; but by that time Seton herself was in danger of dying, for the cold and damp of the prisons she shared with the Queen had affected her health so severely that Mary had to command her to go away and save her life.

“I must bear these hardships,” Mary had said. “But there is no need for you to. I would rather have you living away from me, dearest Seton, than staying here a little longer to die.”

So Seton had at last been persuaded, but only when she was too sick for argument, to go to Mary’s aunt Renée at the Rheims convent. How overjoyed Mary would have been could she have accompanied her! But not for Mary was the seclusion of the nunnery; she must endure her damp prisons. She had come near to death through rheumatic fever and, after a miraculous recovery, was often attacked by such pains that she could not walk for days at a time.

And at last she had come to Fotheringhay. There were only a few more hours left to her in this last of her prisons before she passed on to another life.

The long weary years had gone; but many of them had been filled with hopes. There had been suitors for her hand. Norfolk was one, and he had lost his head because he had become involved with her. Did she bring bad luck to those who loved her? Don John of Austria was another. He was dead now—some said he died by poison.

There had been many plots which had filled her with temporary hopes; plots with Norfolk, the Ridolfi plot, and, last of all, the Babington plot.

IT WAS six o’clock on the morning of February 8, 1587.

Turning to her women, Mary said: “I have but two hours to live. Dry your eyes and dress me as for a festival, for at last I go to that for which I have longed.”

But she had to dress herself—her women’s fingers faltered so. They could not see her clearly for the tears which filled their eyes.

She put on her crimson velvet petticoat, her green silk garters and shoes of Spanish leather. She picked up her camisole of finest Scotch plaid which reached from her throat to her waist.

“For, my friends,” she said, “I shall have to remove my dress, and I would not appear naked before so many people who will come to see me die.”

She put on her dress of black velvet, spangled with gold, and her black satin pourpoint and kirtle; her pomander chain was about her neck, and at her girdle were her beads and cross. Over her head she wore white lawn trimmed with bone lace.

“Watch over this poor body in my last hour,” she said to her weeping women, “for I shall be incapable of bestowing any care upon it.”

Jane Kennedy flung herself on her knees and declared that she would be there to cover her dearest mistress’s body as it fell.

“Thank you, Jane,” said Mary. “Now I shall pray awhile.”

She knelt before the altar in her oratory and prayed for the forgiveness of her sins. “So many sins,” she murmured. “So many foolish sins….”

She prayed for poor Anthony Babington who had given his name to the plot which had finally brought her to this … a young man in her service who had loved her as so many had done. Poor Anthony! He had paid the price of his devotion. He had suffered horrible torment at Tyburn, that crudest of deaths which was accorded to traitors.

And now she herself faced death.

She took the consecrated wafer which the Pope had sent her, and administered the Eucharist herself—a special concession from the Pope which had never before been allowed a member of the laity.

Then she prayed again for courage to face her ordeal, and remained on her knees until morning dawned.

TOO SOON they came to take her to the hall of execution.

She rose from her knees but she found it difficult to walk without aid, so crippled with rheumatism were her limbs.

Her servants helped her but, when she reached the door of the gallery, they were stopped by the Earls of Shrewsbury and Kent and told that the Queen must proceed alone.

There was great lamentation among her servants, who declared they would not leave their mistress. Mary implored the Earls to grant her this last request.

“It is unmeet,” said the Earl of Kent, “troublesome to Your Grace and unpleasing to us. They would put into practice some superstitious trumpery, such as dipping their handkerchiefs into Your Graces blood.”

“My lord, you shall have my word that no such thing shall be done.”

Finally the two Earls gave her permission to take with her as escort, two of her women and four of her men. She took sir Andrew Melville, Master of her Household; Bourgoigne, her physician; Gourion, her surgeon; and Gervais, her apothecary for the four men; and the two women were her beloved Jane Kennedy and Elizabeth Curie.

As she was assisted slowly and painfully down the staircase to the hall, she saw that Andrew Melville was overcome by his grief.

“Weep not, Melville,” she said. “This world is full of vanities and full of sorrows. And fortunate I am to leave it. I am a Catholic, dear Melville, and you a Protestant; but remember this, there is one Christ. I die, firm in my religion, a true Scotswoman and true to France. Commend me to my sweet son. Tell him to appeal to God and not to human aid. Let him learn from his mothers sorrows. May God forgive all those who have long thirsted for my blood as the hart doth for the brooks of water. Farewell, good Melville. Pray for your Queen.”

Melville could not answer her. He could only turn away while the uncontrollable sobs shook his body.

Into the hall of death she went. Melville bore her train, and Jane and Elizabeth, who had put on mourning weeds, covered their faces with their hands so that only their shaking bodies betrayed their grief.

Mary saw that a platform had been set up at the end of the hall. A fire was burning in the grate. She saw the platform, covered with black cloth; she saw the ax and the block.

She reached the chair—also black-covered—which had been provided for her, but she could not, without aid, mount the two steps to reach it.

As she was helped to this, she said in a clear voice: “I thank you. This is the last trouble I shall ever give you.”

The death warrant was read to her. The Dean of Peterborough pleaded with her to turn from the Catholic Faith while there was yet time. To both she preserved a dignified indifference.

The moment of death was drawing near. The executioner was, in the traditional manner, asking her forgiveness.

“I forgive you with all my heart,” she cried.

Looking about her she prayed silently for courage. It was not her enemies who unnerved her. It was Jane Kennedy’s quivering body, Elizabeth Curie’s suppressed sobbing, Andrew Melville’s tears and the sad looks of the others which made her want to weep.

Her uncle, the great Balafré, had once told her that when her time came she would know well how to die, for she possessed the courage of the Guises.

She was in urgent need of that courage now. Her two women had come forward to help her prepare herself. She kissed them and blessed them, but they could do little to help her remove her gown; their fingers trembled, but the Queens were steady. She stood calm and brave in her camisole and red velvet petticoat, while Jane Kennedy fumbled with the gold-edged handkerchief which she tied over her mistress’s eyes.

Now Mary was shut away from the hall of tragedy; she could no longer see the faces of those who loved her, distorted with grief; she was shut in with her own courage.

Jane had flung herself at her mistress’s feet and was kissing her petticoat. Mary felt the soft face and knew it was Jane.

“Weep not, dear Jane,” she said, “but pray for me.”

She knelt there on the cushion provided for her, murmuring: “In thee, Lord, have I hoped. Let me never be put to confusion.”

Groping, she felt for the block; the executioner guided her to it. She laid her head upon it saying: “Into Thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit.”

Bulle, the executioner, hesitated. This was his trade; his victim had forgiven him, knowing this; yet never before had he been called upon to wield the ax for one who affected him so deeply with her grace and dignity.

Every eye in the hall was upon him. He faltered. He dealt a blow. There was a gasp from the watchers, for the ax had slipped and though the blood of Mary Stuart gushed forth, she was merely wounded.

Trembling, Bulle again raised his ax; but his nerve was affected. Again he struck, and again he failed to complete his work.

It was with the third stroke that he severed the Queen’s head from her body.

Then he grasped the beautiful chestnut hair, crying: “God save Queen Elizabeth! So perish all her enemies.”

But the head had rolled on to the bloodstained cloth which covered the scaffold, and it was a wig which the executioner held up before him.

There was silence in the hall as all eyes turned to the head with the cropped grey hair—the head of a woman grown old in captivity.

And as they watched, they saw a movement beneath the red velvet petticoat, and Mary little Skye terrier, who unnoticed had followed his mistress into the hall, ran to the head and crouched beside it, whimpering.

The silence was only broken by the sounds of sobbing.

The Queen of Scotland and the Isles had come to the end of her journey—from triumph and glory to captivity, from joy to sorrow, from the thrones of France and Scotland to the ax in the hall of Fotheringhay Castle—and to peace.

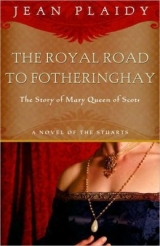

ABOUT THE BOOK

From the time she was a child, Mary Stuart knew she was Queen of Scotland—and would someday rule as such. But before she would take the throne, she would spend her childhood in the court—and on the throne—of France. There she would fall under the influence of power-hungry relatives, develop a taste for French luxury and courtly manners, challenge the formidable Queen of England and alienate the Queen-Mother of France, and begin to learn her own appeal as a woman and her role as a queen.

When she finally arrived back in Scotland, Mary’s beauty and regal bearing were even more remarkable than they had been when she left as the child-queen. Her charming manner and eagerness to love and be loved endeared her to many, but were in stark contrast to what she saw as the rough manners of the Scots. Her loyalty to Catholicism also separated her from her countrymen, many of whom were followers of the dynamic and bold Protestant preacher John Knox. Though she brought with her French furnishings and companions to make her apartments into a “Little France,” she would have to rely on the Scottish Court—a group comprised of her half brother, members of feuding Scottish clans, and English spies—to educate her in the ways of Scottish politics. However wise or corrupt her advisors, however, Mary often followed the dictates of her own heart—to her own peril.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1  What do you think of her mother’s decision to send Mary to France? Were her childhood there and her marriage to François useful in strengthening her claim to Scotland and England’s throne or detrimental to it? Did the power of Guise and Loraine help her in Scotland? How do you think Mary—as a queen and as a woman—would have been different had she remained in Scotland as a child?

What do you think of her mother’s decision to send Mary to France? Were her childhood there and her marriage to François useful in strengthening her claim to Scotland and England’s throne or detrimental to it? Did the power of Guise and Loraine help her in Scotland? How do you think Mary—as a queen and as a woman—would have been different had she remained in Scotland as a child?

2  After the death of her young husband François, Mary realizes “love which she only knew went so deep since she had lost him.” Is this feeling brought about by the end of a romantic love and soulmate, or the loss of an old and dear friend? Is she more moved by the change in her stature in the Court and her uncertain future, or by the end of the relationship that had sustained it?

After the death of her young husband François, Mary realizes “love which she only knew went so deep since she had lost him.” Is this feeling brought about by the end of a romantic love and soulmate, or the loss of an old and dear friend? Is she more moved by the change in her stature in the Court and her uncertain future, or by the end of the relationship that had sustained it?

3  François once complained, “My mother loves me because I am the King; she loves Charles because, if I die, he will be King.” Mary tried to comfort him, but there is some truth to his understanding of the Court’s affection for power over people. Is Mary mindful of this in her own court in Scotland? Who do you think is truly loyal to Mary, and who only interested in her power?

François once complained, “My mother loves me because I am the King; she loves Charles because, if I die, he will be King.” Mary tried to comfort him, but there is some truth to his understanding of the Court’s affection for power over people. Is Mary mindful of this in her own court in Scotland? Who do you think is truly loyal to Mary, and who only interested in her power?

4  Do you think that the Cardinal’s relationship with Mary ever crossed a line of impropriety? How did he maintain control over Mary?

Do you think that the Cardinal’s relationship with Mary ever crossed a line of impropriety? How did he maintain control over Mary?

5  What do you make of Mary’s three husbands: the weak but kind François, the deceptive and romantic Darnley, and the rough and virile Bothwell? What do the differences between them say about Mary’s changing understanding of herself, her role as Queen, and the role of love in her life? Does she ever understand true love?

What do you make of Mary’s three husbands: the weak but kind François, the deceptive and romantic Darnley, and the rough and virile Bothwell? What do the differences between them say about Mary’s changing understanding of herself, her role as Queen, and the role of love in her life? Does she ever understand true love?

6  There are a number of strong women in Mary’s life: her own mother, Catherine de Medici, Diane, Queen Elizabeth. What does Mary learn from them, if anything? Why does she rely so heavily on men for guidance?

There are a number of strong women in Mary’s life: her own mother, Catherine de Medici, Diane, Queen Elizabeth. What does Mary learn from them, if anything? Why does she rely so heavily on men for guidance?

7  Why does Mary refuse to renounce her claims to the English throne when she has so little interest in governing? Is this pride or ignorance?

Why does Mary refuse to renounce her claims to the English throne when she has so little interest in governing? Is this pride or ignorance?

8  During her time in Scotland, it is always uncertain to what degree Mary can trust the men around her, who seem foremost driven by their own ambitions. With whom do you think she should have allied herself in the Scottish Court?

During her time in Scotland, it is always uncertain to what degree Mary can trust the men around her, who seem foremost driven by their own ambitions. With whom do you think she should have allied herself in the Scottish Court?

9  Is John Knox correct that Mary’s weakness is tolerance? Discuss the way she dealt with Knox’s challenges. Was she strong enough in her response? Should she have tried to work closely with him? Exiled him from Scotland? How does she understand his role in Scotland?

Is John Knox correct that Mary’s weakness is tolerance? Discuss the way she dealt with Knox’s challenges. Was she strong enough in her response? Should she have tried to work closely with him? Exiled him from Scotland? How does she understand his role in Scotland?

10  Is there a guiding principle to Mary’s reign in Scotland? How does her rule there relate to her reign as Queen of France? What could she hope to gain by ruling England, as well?

Is there a guiding principle to Mary’s reign in Scotland? How does her rule there relate to her reign as Queen of France? What could she hope to gain by ruling England, as well?

11  Plaidy writes that Elizabeth was ruled by ambition and Mary by emotion. If they had met at the border as Mary wished, how would this meeting have played out? Why was Elizabeth reluctant to meet her?

Plaidy writes that Elizabeth was ruled by ambition and Mary by emotion. If they had met at the border as Mary wished, how would this meeting have played out? Why was Elizabeth reluctant to meet her?

12  In cases of torture or harsh punishments—such as when traitors are hanged in France or slaves on her ship are whipped—Mary sometimes strongly objects and makes a bold stand to stop it. But when traitors are drawn and quartered in Scotland, Plaidy writes that Mary “could not prevent it.” Why could she not prevent it? Is this a sign of her growing ineffectuality as she falls deeper in love with Bothwell, or is she beginning to see the truth of Catherine’s warning: “Your Majesty will never know how to reign if you do not learn how to administer justice”?

In cases of torture or harsh punishments—such as when traitors are hanged in France or slaves on her ship are whipped—Mary sometimes strongly objects and makes a bold stand to stop it. But when traitors are drawn and quartered in Scotland, Plaidy writes that Mary “could not prevent it.” Why could she not prevent it? Is this a sign of her growing ineffectuality as she falls deeper in love with Bothwell, or is she beginning to see the truth of Catherine’s warning: “Your Majesty will never know how to reign if you do not learn how to administer justice”?

13  Mary finds herself feeling and behaving most like a queen when faced with conflict and danger. Does she encourage such moments or avoid them? What does it mean to her to be regal?

Mary finds herself feeling and behaving most like a queen when faced with conflict and danger. Does she encourage such moments or avoid them? What does it mean to her to be regal?

14  How do the differences between her French upbringing and her Scottish homeland contribute to Mary’s downfall? Does she act the way she does because she believes her behavior would be accepted in the French court, or has she determined to set her own rules in Scotland? How much is her imprisonment and death a result of her own actions, and how much is she a victim of her situation?

How do the differences between her French upbringing and her Scottish homeland contribute to Mary’s downfall? Does she act the way she does because she believes her behavior would be accepted in the French court, or has she determined to set her own rules in Scotland? How much is her imprisonment and death a result of her own actions, and how much is she a victim of her situation?