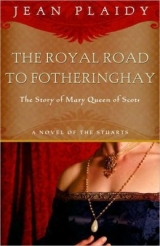

Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

THE MEETING between the children was unceremonious as it had been intended it should be. In the big room at Carrières Mary went forward to greet them. With them were their Governor and Governess, the Maréchal d’Humières and Madame d’Humières. With Mary were her grandmother and the members of her suite.

The Dauphin stared at Mary. She was taller than he was. His legs were thin and spindly and it seemed as though the weight of his body would break them. His head seemed too large for the rest of him and he was very pale.

Mary’s tenderness—always ready to be aroused—overwhelmed her. She knelt and kissed his hand. He stared at her wonderingly; and rising she put her arms about him and kissed him. “I have come to love you and be your playmate,” she said.

The little boy immediately responded to her embrace.

Mary broke away and glanced with some apprehension at her grandmother. They had said no ceremony, but had she been too impulsive in embracing the Dauphin?

The Duchesse was far from displeased. She had noticed the little boys response. She glanced at Madame d’Humières. What a pity that the King is not here to see this! that glance implied. He would be quite enchanted.

Madame d’Humières nodded in agreement. It was always wise to agree with the Guises, providing such agreement would not be frowned on by the King’s mistress.

Mary had turned to the three-and-a-half-year-old Elisabeth, a frail and pretty little girl; and what a pleasure it was for the Duchesse to see a princess of France kneel to her granddaughter! Madame Elisabeth knew what was expected of her. Had not the King said: “Mary Stuart shall be as one of my own children, but because she is a queen she shall take precedence over my daughter”?

Mary looked into the face of the little girl and, because the child was so small and because she had embraced her brother, the little Queen could not resist embracing the Princess also.

Her grandmother advanced toward the group, at which the two royal children seemed to move closer to Mary as though expecting she would protect them from her important relative.

But the Duchesse merely smiled at them and turned to the Maréchal and Madame d’Humières.

“So charming, is it not?” she said. “The King will be delighted. They love each other on sight. Let us leave them together. Then they will be more natural, and when the King slips in unceremoniously he will be delighted with our way of bringing them together.”

When Mary was alone with the two children, she took a hand of each and led them to the window seat.

“I have just come here,” she said. “First I came on a big ship. Then I rode in a litter. Then I came on another ship. I have come from far… far away.”

The Dauphin held her hand in his and clung to it when she would have released it. Elisabeth regarded her gravely. Neither of the French children had ever seen anyone quite like her. Her flashing eyes, her vivacious manners, her strange dress and her queer way of talking overwhelmed and fascinated them. Elisabeth’s gravity broke into a quiet smile and the Dauphin lifted his shoulders until they almost touched his big head; and all the time he insisted that his hand should remain in that of the newcomer.

He was already telling himself that he was never going to let her go. He was going to keep her with him forever.

MARY HAD LIVED at Carrières for two weeks. She was the Queen of the nurseries. Elisabeth accepted her leadership in everything they did; François asked nothing but to be her devoted slave.

She was a little imperious at times, for after all she was older than they were; she was so much cleverer. She read to them; she would sit on the window seat, her arm about François while Elisabeth tried to follow the words in the book. She told them stories and of games she had played with her four Marys with whom she hoped soon to be reunited; she told of the island of Inchmahome in the lake of Menteith whither she had gone one dark night, wrapped in a cloak, fleeing from the wicked English. She told of the long journey across the seas, of the high waters and the roaring winds and of how the English ships had sighted hers on the horizon, for of course they were on the prowl looking for her.

These adventures made her an exciting person; her age made her such a wise one; and her vitality, so sadly lacking in the French children, made her an entertaining companion; but perhaps it was her beauty which strengthened her power.

Thus it was when one day there came into the nurseries unannounced a tall man with a beard which was turning to silver; he was dressed in black velvet and there were jewels on his clothes. With him came a lady—the loveliest Mary had ever seen.

The children immediately ran forward and threw themselves at the man. This was one of the occasions to which they looked forward. If there had been others present it would have been necessary to bow and kiss hands, but this was one of those pleasurably anticipated occasions when the two came alone.

“Papa! Papa!” cried François.

The big man picked him up and the lady kissed Francois’s cheek.

Elisabeth was holding fast to his doublet and there was love and confidence in the way her little fingers curled about the black velvet.

“This will not do! This will not do!” cried the man. “My children, what of our guest?”

Then he lowered François to the floor. François immediately caught the lady’s hand and they all advanced to the Queen of Scots who had fallen to her knees, for she knew that the big man with the silvering beard was Henri, King of France.

“Come,” he said in a deep rumbling voice which Mary thought was the kindest she had ever heard, “let us look at you. So you are Mary Stuart from across the seas?”

“At Your Majesty’s service,” said Mary.

He laid his hand on her head and turned to the lady beside him. “I think we shall be pleased with our new daughter,” he said.

Mary flushed charmingly and turned to kneel to the lady. She took the slim white hand and kissed the great diamond on her finger.

“Yes, indeed,” said the lady, “our new daughter enchants me.”

“I am happy,” said Mary, in her charming French, “to know that I have not displeased Your Majesties.”

They laughed and the Dauphin said: “Mary has come across the sea. She came on a boat and then on another boat and she reads to us.”

The King stooped then and picked up the boy, swinging him above his head. “You must borrow Marys rosy looks, my son,” he said.

Elisabeth was quietly waiting to be picked up and kissed, and when it was her turn she put her arms about her fathers neck and kissed him; then she buried her face in his beard.

The beautiful lady, whom Mary assumed to be the Queen, said: “Come and kiss me, Mary.”

Mary did so.

“Why, what a fine girl you are!” The soft white fingers patted Mary’s cheeks. “The King and I are glad you have come to join our children.” She smiled fondly at the King who returned the smile with equal fondness over the smooth head of Elisabeth. In a sudden rush of affection for them both, Mary kissed their hands afresh.

“I am so happy,” she said, “to be your new daughter.”

The King sat in the big state chair which was kept in the apartment for those occasions when he visited his children. He took Mary and the Dauphin on his knees. The lady sat on a stool, holding Elisabeth.

The King told them that there was to be a grand wedding at the Court. It was Mary’s uncle who was to be married.

“Now, my children, Mary’s uncle, the Due d’Aumale, must have a grand wedding, must he not? He would be displeased if the Dauphin did not honor him by dancing at his wedding.”

The Dauphin’s eyes opened wide with horror. “Papa… no!” he cried. “I do not want to dance at the wedding.”

“You do not want to dance at a fine wedding! You do, Mary, do you not?”

“Yes, I do,” said Mary. “I love to dance.” She put out her hand and took that of the Dauphin. “I will teach you to dance with me, François. Shall I?”

The grown-ups exchanged glances and the King said in rapid French which Mary could not entirely understand: “This is the most beautiful, the most charming child I ever saw.”

THE CHILDREN were alone. Mary was explaining to the Dauphin that there was nothing to be frightened of in the dance. It was easy to dance. It was delightful to dance.

“And the King wishes it,” said Mary. “And as he is the best king in the world, you must please him.”

The Dauphin agreed that this was so.

While they practiced the dance, Elisabeth sat on a cushion watching them. The door silently opened, but Mary did not hear it, so intent was she on the dance. She noticed first the change in Elisabeth who had risen to her feet. The smile had left Elisabeth’s face. She seemed suddenly to have become afraid. Now the Dauphin had seen what Elisabeth saw. He too stood very still, like a top-heavy statue.

There was a woman standing in the doorway, a woman with a pale flat face and expressionless eyes. Mary took an immediate dislike to her, for she had brought something into the room which Mary did not understand and which was repellent to her. The woman was dressed without magnificence and Mary assumed that she was a noblewoman of minor rank. Hot-tempered as she was, she let her anger rise against the intruder.

As Queen of the nursery, the spoiled charge of easy-going Lady Fleming, the petted darling of almost everyone with whom she had come into contact since her arrival in this country, fresh from her triumph with the King, she said quickly: “Pray do not interrupt us while we practice.”

The woman did not move. She laughed suddenly and unpleasantly. The little French children had stepped forward and knelt before her. Over their heads she regarded the Queen of Scots.

“What will you do, Mademoiselle?” asked the woman. “Are you going to turn me out of my nurseries?”

“Madame,” said Mary, drawing herself to her full height, “it is the Queen of Scotland to whom you speak.”

“Mademoiselle,” was the reply, “it is the Queen of France to whom you speak.”

“N-No!” protested Mary. But the kneeling children had made her aware of the unforgivable mistake she had made. She was terrified. She would be sent back to Scotland for such behavior. She had been guilty not only of a great breach of good manners; she had insulted the Queen of France.

“Madame,” she began, “I humbly beg …”

Again the harsh laugh rang out; but Mary scarcely heard it as she knelt before the Queen, first pale with horror, then red with shame.

“We all make mistakes,” said Catherine de Médicis, “even Queens of such great countries as Scotland. You may rise. Let me look at you.”

As Mary obeyed she realized that there were two queens: one lovely and loving who came with the King, who kissed the children and called them hers and behaved in every way as though she were their mother, and another who came alone, who frightened them and yet, it seemed, was after all their mother and the true Queen of France.

TWO

TO MARY, LIFE IN THOSE FIRST MONTHS WAS FULL OF PLEASURE. It was true there were times when the Queen of France would come silently into the nursery, laugh her sudden loud laughter, make her disconcerting remarks, and when little François and Elisabeth would, while displaying great decorum, shrink closer to Mary as though asking her to protect them. But Mary was gay by nature and wished to ignore that which was unpleasant.

Often King Henri and Madame Diane came to the nursery to play with them, to caress them and make them feel secure and contented. It had not taken Mary long to discover that if Queen Catherine were Queen in name, Diane was Queen in all else.

Mary noticed that, when Catherine and Diane were together in the nursery, Catherine seemed to agree with all Diane’s suggestions. Being young, being fierce in love and hate, young Mary could not resist flashing a look of triumph at the Queen’s flat, placid features at such times.

She is a coward! thought Mary. She is not fit to be a queen.

The four Marys were now added to the little Queens adoring circle, but the Dauphin had become her first care. All those who saw Mary and the Dauphin together—except Queen Catherine—declared they had never seen such a charming love affair as that between the Dauphin and his bride-to-be. As for little Madame Elisabeth, she became one of Mary’s dearest friends, sharing her bedchamber and following her lead in all things.

It was at the wedding of her uncle François Duc d’Aumale that she met this important man for the first time. He looked very like the knight she had pictured during her childhood in Scotland and she was not disappointed in the eldest of her uncles. François de Guise, Duc d’Aumale, was tall and handsome; his beard was curled; his eyes were flashing; and he was gorgeously appareled. He was ready to become—as he soon was to be—the head of the illustrious family of Guise. He filled the role of bridegroom well, as he did that of greatest soldier in the land. His bride was a fitting one for such a man. She was Anne d’Esté, the daughter of Hercule, Duke of Ferrara, and was herself royal, for her mother was King Henri’s aunt.

There was a good deal of whispering in the Court concerning the marriage. “Watch these Guises,” said suspicious noblemen. “They look to rule France one way or another. Old Duke Claude had not the ambition of his sons; that doubtless came from their Bourbon mother. But Duke Claude, who was content with the hunt, his table and his women, is not long for this world and then this Due d’Aumale will become the Duc de Guise, and he looks higher than his father ever did.

Mary heard nothing of these whisperings. To her the marriage was just another reason for merriment, for wearing fine clothes, for showing off her graces, for being petted and admired for her beauty and charm.

So there she was in the salle de bau stepping out to dance with the Dauphin, enchanting all with her grace and her beauty and her tender devotion to the heir of France.

“Holy Mother of God!” swore the Due d’Aumale. “There goes the greatest asset of the House of Guise. One day we shall rule France through that lovely girl.”

LATER HE TALKED with his brother Charles. Charles, five years younger than his brother François, was equally handsome though in a different way. François was flamboyantly attractive but Charles had the features of a Greek god. Charles’s long eyes were alert and cynical. François would win his way through boldness, Charles by cunning. Charles was the cleverer of the two, and knowing himself to lack that bravery on which the family prided itself, he had to develop other qualities to make up for the lack.

So Charles, the exquisite Cardinal, with his scented linen and his sensuality, was an excellent foil to his dashing brother; they were both aware of this, and they believed that between them they could rule France through their niece who in her turn would rule the Dauphin.

They had brought rich presents for Mary; they were determined to win her affection and to increase that respect which their sister, the Queen-Mother of Scotland, had so rightly planted in her daughter’s mind.

The Cardinal, whose tastes were erotic and who, although he was quite a young man, was hard pressed to think of new sensations which could delight him, was quite enchanted with his niece.

“For, brother,” he said, “she has more than beauty. There is in her… shall we call it promise? What could be more charming than promise? She is like a houri from a Mohammedan paradise, beckoning the newcomer to undreamed of delight, inviting him to explore with her that which she herself has not yet discovered.”

François looked at his brother uneasily. “Charles, for God’s sake, do not forget that she is your niece.”

Charles smiled. Blood relationships were of no account in his world of licentiousness. His long slim fingers a-glitter with jewels which put those adorning his brother’s person in the shade, stroked his cardinal’s robes. Did he enjoy being a man of the church so much because, in his relationships with charming people, that fact added an extra relish? François was a blunt soldier for all that he was a Guise and destined, Charles was sure, to be one of the great men of his day. Rough soldier—he took the satisfaction of his carnal appetites as a soldier takes them. Charles was selective, continually striving for the new sensation.

“My dear brother,” he said, “do you take me for a fool? I shall know how to deal with our niece. She is a little barbarian at the moment, from a land of barbarians. We shall teach her until she is cultured and even more charming than she already is. But the material is excellent, François, excellent.” The Cardinal waved his beautiful hands describing the shape of a woman. “Beautiful… malleable material, dear François.”

“There must be no scandal touching her, Charles. I beg of you to remember that.”

“François! My dear soldier brother! You are a great man. You are the greatest man in France. Yes, I will say that, for there is none here to repeat my words to his boorish Majesty. But you have lived the life of a soldier, and the life of the soldier, you will admit, is one that lacks refinement. I am in love with Mary Stuart. She is an enchanting creature. Dear brother, do not think that I mean to seduce her. A little girl of six? Piquant… yes. But if I want little girls of six, they are mine. It is her mind that I shall possess. We shall possess it between us. We shall caress it… we shall impregnate it with our ideas. What pleasure! I have long since known that the pleasure of the body—after the first rough experimenting—cannot be fully enjoyed without the cooperation of the mind.”

Francois’s brow cleared. Charles was no fool. No fool indeed! If he himself was Frances greatest soldier, Charles would be the country’s cleverest diplomat.

“I feel,” said François, “that you should watch over her education carefully, and that the Maréchal and Madame d’Humières should not be given too free a hand. The governess, Fleming, is no danger, I suppose?”

“The governess Fleming is just a woman.”

“If you wish to seduce a royal lady of Scotland, why not…,” began François.

The cynical mouth turned up at the corners. “Ten years ago your suggestion would have interested me. The Fleming will be a worthy lover. Very eager she will be. She is made for pleasure. Plump and pretty, ripe, but of an age, I fear, for folly, and the folly of the middle-aged is so much more distressing and disconcerting than that of youth. But there are hundreds such as the Fleming. They are to be found in every village in France. Nay, I’ll leave the Fleming for some callow boy. She’ll bring him much delight.”

“You could, through the woman, keep a firm hand on Mary Stuart.”

“The time is not yet come. Mary, at the moment, is the playmate of the Dauphin, and as such shares the governor and governess of young François. That is enough for the moment. Let her strengthen that attachment. That is the most important thing. The Dauphin must be completely enslaved; he must follow her in all things. He is willing to do so now, but she must forge those chains strongly so that they can never be broken. He is his father all over again. Would Diane have caught our Henri so slavishly if she had not caught him young? ‘How charming!’ they say. Madame Diane says it. His Majesty says it. ‘Was there ever anything more delightful than for two children who are destined for marriage to be already such tender playmates?’ These Parisians! They are not like us of Lorraine. They talk love and think love. It is their whole existence; it is an excuse for everything. It is typically Valois. But we must be more clever; we must see farther. We know that this love between our niece and the King’s son is more than charming; it is very good for the House of Guise. Let us therefore help to forge those chains, chains so strong that they cannot be broken, for depend upon it, sooner or later the Montmorencys—or mayhap our somnolent Bourbons—will awake from their slumbers. They will see that it is not a pretty little girl who has made the King-to-be her slave; it is the noble House of Guise.”

“You are right, Charles. What do you suggest?”

“That she remains at present as she is. The chattering Fleming will be useful. She—herself the slave of love—will be delighted to see her mistress installed in the heart of our Prince. She will chatter romance; she will foster romance; and she will do no harm. Leave things as they are, and in a few years’ time I shall take over Mary’s education. I shall teach her to be the most charming, the most accomplished lady in France. None shall be as beautiful as she, none shall excel her at the dance, at the lute; she will write exquisite verses, and all France—but most of all the Dauphin—will be in love with her. Her mind shall be given to the art of pleasing others; and it shall be as wax in the hands of the uncles who will love and cherish her, for their one desire will be to keep her on the throne.”

François smiled at his elegant brother.

“By God!” he cried suddenly. “You and I will conquer France and share the crown.”

“In the most decorous manner,” murmured Charles. “Through our little charmer from the land of savages.”

THE DAYS flew past for Mary. At lessons she excelled; she played the lute with a skill rare in one so young; she was a good horsewoman. In the royal processions she was always picked out for her charm and beauty. The King often talked to her. Diane was delighted with her. When she rode out with the Dauphin she would watch over him and seize his bridle if he was in any difficulty. He would be uneasy if she was not always at his side.

All the great châteaux which had been but names to her she now saw in reality. She thought less and less of her native land. Her mother wrote frequently and was clearly delighted with her daughters success. She had had letters from the King, she said, which had made her very happy indeed.

Mary’s four namesakes were now with her, but they had to take second place. The Dauphin demanded so much of her time. She explained this carefully to them for she was anxious that they should know that she loved them as dearly as ever.

They listened to gossip, and there was plenty of that at the French Court. Now the talk was all about the Queens coronation which was about to take place. The King had already celebrated his coronation shortly after the death of his father, and now it was Catherine’s turn.

The celebrations were lavish. Mary had never seen anything quite so wonderful. Even the dreamlike pageants which had accompanied her uncle’s wedding seemed commonplace when compared with those of the Queen’s coronation. Even the Queen looked magnificent on that day. As for the King he was a dazzling sight, resplendent in cloth of silver; his scabbard flashed with enormous jewels, and his silver lace and white satin hat were decorated with pearls. The sheriffs of Paris held over him a blue velvet canopy embroidered with the golden lilies of France as he rode his beautiful white horse.

Mary would never forget the display of so much beauty. She was, she told Janet Fleming, only sorry that it was not her beloved Diane, instead of Queen Catherine, who was being crowned.

“Well, let her enjoy her coronation,” said Lady Fleming. “That’s all she’ll get.”

“All! A coronation all! Dear old Fleming, what more could she want?”

“She wants much more,” said Lady Fleming. “Whom do you think the King has presented with the crown jewels?”

“Diane, of course.”

Lady Fleming nodded and began to laugh. “And she wears them too. She insists. The King is pleased that she should. What a country! The old Maréchal Tavannes complains that at the Court of France more honor is done to the King’s mistress than to his generals. Who is the real Queen of this country, tell me that!”

“Diane, of course. And I am glad that it should be so, for I hate Queen Catherine.”

“She is not worth the hating. She is as meek as a sheep. Look at this. It is one of the new coins struck at the coronation and should bear the heads of the King and Queen. But see! It is Diane riding on the crupper of the Kings horse. It means that although he has been forced to marry Queen Catherine and make her the mother of his children, there is only one Queen for him—Diane.”

“And more worthy to be!” cried Mary. “Queen Catherine is not royal. She has no breeding. She is vulgar. I wish she would go back to her Italian merchants so that the King could marry Diane.”

They looked up sharply. The door had opened so quietly that no one had heard a sound. They were relieved to see that it was not Catherine who stood there; it was Madame de Paroy.

“Yes, Madame de Paroy?” said Mary, immediately assuming the dignity of her rank. “What is it you want?”

“To ask your Majesty if you would wait on Queen Catherine.”

“I will do so,” said Mary. “And, Madame de Paroy, when you come to my apartments will you be so good as to be announced?”

“I could find none of your pages or women, Your Majesty. I am sorry that, as you and Lady Fleming were enjoying such mirth, you did not hear me.”

Madame de Paroy curtsied and retired. Mary looked at Lady Fleming who was trembling.

“Why are you afraid, and of what?” demanded Mary.

“I am afraid that she will tell Queen Catherine what she heard you say.”

Mary tossed her head. “Who cares for that! If Queen Catherine were unpleasant to me I should ask Diane to protect me.”

“There is something about her that frightens me,” said Janet.

“You are too easily frightened, Fleming dear.”

“Do not keep her waiting. Go to her now… at once. I shall not rest until I know what she has to say to you.”

Mary obeyed. She returned very shortly.

“You see, you silly old Fleming, it was nothing. She just wished to speak to me about our lessons.”

DIANE HAD fallen ill and had retired to her beautiful château of Anet which enhanced the beauty of the valley of the Eure and which Philibert Delorme had helped her to make one of the most magnificent examples of architecture in the country. The King, filled with anxiety, would have dropped all state obligations to be with her, but Diane would not hear of it. She insisted on his leaving her in her château with her faithful servants, and continuing with his Court duties.

Everyone in the Court was clearly delighted or anxious—except, of course, the Queen. She, who would surely be most affected, remained as expressionless as ever; and whenever Diane’s name was mentioned spoke of her concern for her health.

A melancholy settled over Saint-Germain, and Mary hated melancholy. When the King visited his children he was absentminded. Nothing was as pleasant as it had been when Diane was there.

Then an alarming incident occurred. Mary would not have heard of this but for the cleverness of Beaton who had quickly improved her French and was now a match for anyone.

Beaton took Mary into a corner to whisper to her: “Someone tried to poison you.”

Mary was aghast. “Who?” she demanded; and her thoughts immediately flew to the Queen.

“No one is sure. It was the poisoner’s intention to put an Italian posset into a pie for you. But it’s all right. They have a man whom they have caught, and I expect they’ll tie him to four wild horses and let them gallop in different directions.”

For once Mary was too horrified by what might be happening to herself to feel sorry for the victim of such a horrible punishment.

Mary Beaton had gleaned no further information, so Mary tackled Janet Fleming. Janet had heard the story, although, she said, the King wished it not to be bruited abroad, for he was much distressed that danger should have come so near Mary when she was at his Court.

“He says that the vigilance about you must be intensified. You must not let anyone know you have heard of this.”

“Tell me who did this thing.”

“A man is accused who is named Robert Stuart. Oh, do not look shocked. It is not your brother but a poor archer of the guard who happens to bear his name. He was clearly working for someone else. Some say it was the English. Others that he worked for your kinsman the Earl of Lennox… a Protestant. And this would seem most likely, as Robert Stuart is clearly a fanatic. He has confessed that he did this thing, and will suffer accordingly. Matthew Lennox declares his innocence, but who shall know?”

“So it was not the Queen,” said Mary.

“The Queen! What do you mean?”

“She hates me. Sometimes I am afraid of her.”

“Nonsense! The Queen is but a name.”

THE KING came into the nurseries to see the children, and with him was the Queen. How different were these visits from those of Henri and Diane! The children did not rush to their father and climb over him; they curtsied and, under their mothers gaze, paid their respectful homage to him as their King.

The Maréchal and Madame d’Humières were not present on this occasion, and Janet Fleming was in charge of the children. Mary noticed how particularly pretty she was looking, and that the glance the Queen threw in her direction seemed to be faintly amused.

Mary wanted to know if there was any news from Anet, but under the eyes of the Queen, she dared not ask.

“Lady Fleming,” said the Queen of France, “now that the Dauphin and the Queen of Scotland and Madame Elisabeth are growing older, and Madame Claude will soon be joining them in the nursery, it seems to me that you will need some assistance.”

“Your Majesty is gracious,” said Janet Fleming, with that abstracted look which Mary had noticed lately.

“I am sure,” said the King, “that Lady Fleming manages very well… very well indeed. I am struck with the great care she has always shown of our daughter Mary.”

The Queen’s lips twitched very slightly. “Like Your Majesty I too am sure that Lady Fleming is admirable, but I do not wish her strength to be overtaxed.”

“Overtaxed?” reflected the King, frowning at his wife.

“By so many children. And the Maréchal and Madame d’Humières have so much with which to occupy themselves. I do not wish dear Lady Fleming to work all the time she is with us, and I should like her to have some little respite from her duties. I should like her to enjoy a little gaiety.”