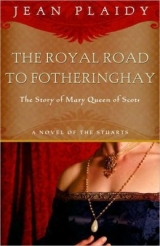

Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

No one spoke in those frightening first moments as Ruthven’s hollow eyes ranged about the room and came to rest on David Rizzio.

Then Mary saw that Ruthven was not alone. Behind him, through the narrow doorway she caught glimpses of Morton, Lindsay, Kerr and others. Ruthven suddenly lifted his hand and pointed to David.

“Come out, David,” he said slowly. “You are wanted without.”

David did not move. His great eyes seemed to have grown still larger; his trembling hand reached for the Queens skirt.

Ruthven began to shout: “Come out, David Rizzio. Come out from the Queens chamber. You have been there too long.”

Mary stood up and confronted Ruthven. “How dare you, my lord, thus come into my chamber? How dare you! You shall pay dearly for this. What means this intrusion? Who are those who follow you here? Why have you comer

“We come for David Rizzio, Madam.”

“Then go away,” commanded the Queen. “If David is here it is my wish that he should be.” She turned fiercely to Darnley: “What means this outrage, my lord? Do you know aught of this?”

Darnley did not reply for a second or so. Then he mumbled: “N-No. But it is a dishonor that David should sup with you, and your husband be kept out.”

Ruthven caught the hangings to prevent himself falling from exhaustion. Mary looked around at the terrified company. Catching her look, Erskine and the Lord of Creich started forward. Ruthven cried in a hollow voice: “Let no one touch me. They will regret it.” He looked supernatural in that moment, and the two men stood where they were as though held there by Ruthven’s uncanny powers.

Mary cried out: “Leave at once! Go! I command you to go.”

“I have come for Rizzio,” persisted the grim-faced Ruthven. And with those words he unsheathed his dagger.

It was the signal. His accomplices rushed into the chamber.

Rizzio gave a great cry and, falling to the floor, gripped Marys skirts and tried to hide himself in their folds. Dishes were swept aside; the table toppled over. The Countess of Argyle picked up the candelabra in time and held it high above her head.

Mary felt the child protest within her; nauseated, she tried not to faint. Rizzio was clinging to her and she made an effort to put herself between him and those men who, she knew, had come to kill him.

George Douglas had twisted Rizzio’s arm so that, with a cry of pain, he released his grip on Mary’s gown.

She saw their faces vaguely, distorted with bloodlust, and the desire to kill not only Rizzio, she believed, but herself and the child she carried.

“Take the Queen,” someone said, and she saw Darnley close beside her. He put an arm about her and held her; she turned from him in revulsion just in time to see George Douglas snatch the dagger from Darnley’s belt and drive it into the cowering, shrieking Rizzio.

Hands were clutching the terrified David who was bleeding from the wound. She watched him as they dragged him across the floor, and his terrified eyes never left her face. She stretched out her arms to him.

“Oh, Davie… Davie …,” she sobbed. “They are killing you, Davie. They are killing us both. Where are my friends? Is this the way to treat the Queen?”

“Be quiet!” hissed Kerr. “If you are not, I shall be forced to cut you into collops.”

She could hear the shrieks in the next chamber to which they had dragged David; she heard the hideous thud of blows. She heard the death agonies of David.

“His blood shall cost you dear!” she cried; and she slid to the floor in a faint.

WHEN MARY came out of the swoon she was aware of Darnley beside her, supporting her. For a moment she was uncertain what had happened to shock her so; then the sight of the room in the light from the candelabra showed her the upturned table, the spilled food and wine and the carpet soaked with David’s blood.

She turned to Darnley and cried out in anguish: “You are the cause of this. Why have you allowed this wicked deed to be done? I took you from low estate and made you my husband. What have I ever done that you should use me thus?”

“I will tell you, Madam,” cried Darnley. She saw his shifty bloodshot eyes; she smelled the wine on his breath and she knew he was not entirely sober. “Since yonder fellow David came into credit and familiarity with you, you have had little time to spare for me. I have been shut from your thoughts and your chamber. You were with David far into the night.”

“It was because you had failed me.”

“In what way? Am I failed in any sort in my body? There was a time when you were so eager for me that you came to my chamber. What disdain have you for me since you favored David? What offense have I committed that you should be coy with me? You have listened to David and he spoke against me.”

“My lord, all that I have suffered this night is your doing, for the which I shall no longer be your wife, nor lie with you anymore. I shall never rest content until I have made you suffer as you have made me suffer this night.”

She could not bear to look at him. She covered her face with her hands and wept bitterly.

Ruthven returned to the chamber.

He said: “His lordship is Your Majesty’s husband, and you must be dutiful one to the other.” As he spoke he sank into a chair from very exhaustion and called for wine to revive him.

Mary went to him and stood over him. “My lord,” she cried, “if my child or I should die through this night’s work, you will not escape your just reward. I have powerful friends. There are my kinsmen of Lorraine; there is the Pope and the King of Spain. Do not think you shall escape justice.”

Ruthven grasped the cup which was offered to him. He smiled grimly as he said: “Madam, these you speak of are overgreat princes to concern themselves with such a poor man as myself.”

Mary stood back from him. She understood his meaning. He was implying that they were too great to concern themselves with the troubles of a queen of a remote country, who could be of little use to them when her nobles had rendered her powerless.

Mary was seized with a great trembling then; for she realized that the folly of Darnley had, by this night’s work, frustrated all her careful plans; all her triumphs of the last months were as nothing now.

Others were hurrying into the room. She saw the mighty figure of Bothwell among them, and her spirits lifted. Rogue he might be, but he was a loyal rogue. With him were Huntley and Maitland of whom she was not quite certain, but could not believe they were entirely against her.

Bothwell cried: “What means this? Who dares lay hands on the Queen?” He seized Ruthven and pulled the dying man to his feet.

“What has been done has been done with the consent of the King,” said Ruthven. “I have a paper here which bears his signature.”

Bothwell seized it. Mary watching, saw the change in his expression and that of Huntley. They at least were outside this diabolical plot.

Morton, who was with them, cried: “The palace is full of those who have had a share in this night’s work.”

Mary’s eyes were fixed on Bothwell, but at that moment there came a shouting from below. The townsfolk of Edinburgh had heard that something was amiss in the palace and had come demanding to see the Queen.

With a sob of relief Mary dashed to the window, but Kerr’s strong arms were about her. She felt his sword pressed against her side while he repeated his threat to cut her into collops if she opened her mouth.

Ruthven signed to Darnley. “To the window. Tell them that the Queen is well. Tell them that this is nothing but a quarrel among the French servants.”

“Henry!” cried Mary. “Do no such thing.”

But Kerr’s hand was over her mouth.

Darnley, alarmed and uncertain, looking from the Queen to Morton and his followers, seeing the murderous light in Morton’s eyes, remembering the groaning, blood-spattered David, allowed himself to be led to the window.

“Good people,” he cried, “there is naught wrong in the palace but some dispute among the French servants. ’Tis over now.”

He turned and looked at Mary’s stricken face. This was the last act of treachery. He was completely against her now.

She looked for Bothwell and Huntley among those who had filled the small chamber. They had disappeared. Maitland had left too. His loyalty was doubtful but she could have trusted his courtesy and gentleness.

She realized then that she was alone with her enemies. Nausea swept over her; the child leaped within her; and once again on that terrible night, she fell fainting to the floor.

THROUGH THE long night she lay sleepless. What now? she asked herself.

There were only a few women in her bedchamber. One of these was old Lady Huntley—Bothwell’s mother-in-law. The others had been appointed by her enemies, and her Marys were absent. There was no one to help her then.

She struggled up and Lady Huntley came to her.

“Where are my women?” she asked. “I wish to get up immediately. I wish to leave the palace.”

“Your Majesty,” whispered Lady Huntley, “that you cannot do. The palace is surrounded by the armed men of your enemies. My son and Lord Bothwell have left Edinburgh in haste. They could do nothing by staying. It would have been certain death. They were here alone, as you know, with few of their men and only a few servants to do their bidding.”

“So I am a prisoner here? But what of the people of Edinburgh? They will come to my assistance. I know it.”

“Your Majesty, they cannot do so. The King has issued a proclamation. He has dissolved Parliament and commanded all burgesses, prelates, peers and barons to leave Edinburgh immediately. The tocsins are sounding.”

“This is a terrible thing that has come upon me,” said Mary. “Is there no man in Scotland on whom I can rely?”

“There are my son, Your Majesty, and my son-in-law.”

“They ran away, did they not, when they scented danger?”

“Only because they can serve you better alive than dead. They have hurried away to muster forces to come to your aid.”

“Many have deceived me,” said Mary. “I trust no one.”

She turned wearily on her side and, being aware of the child, a sudden courage came to her, reminding her that it was not for herself alone she must fight.

The child! She would fight for the child. And in a flash of inspiration she realized that the child might give her the help she needed. They could not deny her a midwife, could they? They could be made to believe that the terrible events of last night had brought about a miscarriage.

She was excited now.

Who could help her in this? Lady Huntley. She was old but she could play her part. Who else… when the palace was held by her enemies?

But there was one of uncertain loyalty. There was a foolish, gullible one. There was one whose craven mind she understood—her husband, Lord Darnley.

She said to Lady Huntley: “They cannot object to my seeing my husband, can they? Go at once and see if you can bring him to me. Tell him that he will find a submissive wife if he will but come to me.”

Darnley came, and as she looked at him, her hope sprang up afresh. He was afraid; he was afraid of her and he was afraid of the lords who—now that the murder was done and done in his name—had hinted that he would do as they bade him.

“My lord …,” said Mary, stretching out her hand.

He took it hesitantly.

“What is this terrible thing which has come between us?” she asked. “What has made you take the side of my enemies against me?”

“It was David,” he said sullenly. “David came between us. He has been your lover. Was I to endure that?”

“Henry, you have allowed these men to play you false. They have tricked you. You must see this now. How have they treated you since the deed was done? They command you to obey them. This was no murder of jealousy. This was a political murder. They wanted David out of the way because David knew how to make us great… us, you too, Henry… you who would have been my King. This was not done because you or they imagined David to be my lover. That was how they used you and how they will continue to use you if you allow them. They promised to make you King, but they will make you powerless. And when my brother returns, they will find some means of dispatching you … as they have dispatched David.”

Darnley’s teeth began to chatter. He was wavering. When he listened to Morton he believed Morton; but now Mary’s version of the motives of these men seemed plausible. They had ordered him to dismiss Parliament. Last night they had ordered him to speak to the people of Edinburgh. He had had no say in either matter. Already he could see the gleam in Ruthven’s eyes; he could see Morton’s tight, cruel lips sneering at him.

“It is my brother whom they will make their leader,” said Mary.

“He … he … is riding with all speed to Edinburgh,” stammered Darnley. “He will be here at any minute.”

“Then you will see how they will treat you. You will not live long to feel remorse for what you have done to David. My brother always hated you. It was because I wished to marry you that he went into exile. We defeated him then; that was because we stood together. Now you have gone over to our enemies who seek to destroy me, our child and you too, Henry. You will not escape. Indeed you will be the first whom they will dispatch. Who knows, they may let me live on as their prisoner.”

“Do not speak so … do not speak so. Do you realize that they are all about us? There are armed men everywhere.”

“Henry, consider this: Help me, and I will help you. You and I must stand together. We must find some way of getting out of here.”

Lady Huntley had come into the room. She said: “Madam, forgive me for breaking in on you thus, but I thought you would wish to know that your brother, the Earl of Moray, has arrived at the palace.”

DARNLEY AND Lady Huntley had left her, and her brother would be with her at any moment now. Lady Huntley had given her a message brought by one of Bothwell’s men and smuggled in to her. It was the most comforting thing that had happened for many terrible hours.

“Do not despair,” began the message.

Do not think Bothwell and Huntley have deserted Your Majesty. They left Holyrood in order to gather forces to come to your aid. Bothwell will soon have a Lowland force ready to fight for you; Huntley too will be there with his Highlanders.

The message went on to say that it was imperative for her to leave the palace as soon as this could be arranged, and Bothwell was forming a plan whereby she would be lowered over the walls by ropes to where he would be waiting for her with horses.

She laid her hands on her heavy body. Bothwell seemed to think she was a hardy adventurer like himself, instead of a woman, six months pregnant. Lowered over walls in her condition! It was impossible.

Still, it was gratifying to know that outside these walls her friends were making plans for her safety.

Nevertheless she must find some way to escape from the palace. She must do it, not by following Bothwell’s wild suggestion, but in a subtler manner; her plan was already beginning to take shape.

Her brother came into the apartment at that moment. He knelt before her. He lifted his face to hers and there were tears in his eyes when he embraced her.

“Dear Jamie,” she said.

“My dearest sister, I blame myself for this terrible thing. I should never have left you. Brothers and sisters should not quarrel. Had I been at hand I should never have allowed you to suffer so.”

Those tears in his eyes seemed to be of real emotion, but she was not so foolish as she had once been. Did he really believe that she did not know he had been in the plot to kill Rizzio? Did he really believe that she did not understand that he had returned to Scotland to wrest her power from her and take it to himself? It was with pleasure that she would deceive him now as he had so often deceived her.

“Jamie,” she said, “you see me a sick woman. My child was to have been born three months from now.”

“Was to have been born?”

“I am in such pain, Jamie… such terrible pain. I fear a miscarriage.”

“But this is more terrible than anything that has happened.”

“You see, Jamie, they have so far taken only my faithful secretary. Now they will take my child as well.”

“You are sure of this?”

She put her hand to her side and groped her way to the bed. Moray was beside her. He put his arm about her.

“Jamie, you will not let them deny me a midwife?”

“No… no… certainly you must have a midwife.”

“And… Jamie … it distresses me … all these men about me … at such a time. I… in my state … to have soldiers at my door. Jamie, look at me. How could I escape in this condition? How could I?”

“I will have a midwife sent to you.”

“I have already asked my woman to bring one. See that she is not kept back, I beg of you.”

Mary turned her head away and groaned. She was enjoying her triumph; she had successfully deceived her brother.

She gripped his hand. “And… the men-at-arms… they distress me so. I … a queen in my own palace … a poor sick woman … a dying woman … to be so guarded. Jamie, it is mayhap my last request to you.”

“No … no. You will soon be better. Dearest sister, I will do all that you ask. I will have the midwife sent to you as soon as she comes. I will see what may be done about clearing the staircases about your apartments.”

“Thank you, Jamie. This would not have happened, would it, had you been here? Oh, what a sad thing it is when a brother and sister fall out. In future, brother, we must understand each other … if I live through this.”

“You shall live, and in future there shall be understanding between us. You will be guided by me.”

“Yes, Jamie. How glad I am that you are back!”

THE “MIDWIFE” had come. She was a servant of the Huntleys and knew that her task was not to deliver a stillborn child but to take charge of letters the Queen had written and see that they were dispatched with all speed to Lords Huntley and Bothwell.

Moray and Morton had decided that if Darnley would stay in the Queens bedchamber all night, the guards about her apartments could be withdrawn. They trusted Darnley, and in any case the Queen was considered far too sick to leave her bed.

In the evening all the lords retired from the palace to Douglas House, the home of Morton, which was but a short step from the palace. There they could feast and talk of the success of their schemes and make future plans.

As soon as they had gone and the sentries had been withdrawn, Mary rose and dressed hastily. Darnley had changed sides completely now that she had inspired him with fear and had promised him a return to her favor. After the child was born they would live as husband and wife again. He had learned a bitter lesson, Mary said; she hoped that in future they would trust each other.

She had satisfied him that the lords who held them prisoners represented but a small proportion of the population. Had he forgotten what had happened when they had married and Moray had believed he would raise all Scotland against her? Who had mustered the stronger force then? She assured him that all he had to do was escape with her from the palace and join Bothwell and Huntley, who were mustering their forces at this very time. Darnley would be a fool if he did not join her, for her friends would have no mercy on him if he did not. Those with whom he had temporarily cast in his lot would have no further use for him either.

So, trembling, Darnley agreed to deceive the lords, who were feasting and congratulating themselves in Douglas House; he would escape with Mary from Holyrood and ride away.

“NOW,” said the Queen.

She was wrapped in a heavy cloak. She stood up firmly. The child was quiet now; it was almost as though it shared the suspense.

“Down the back staircase,” said Mary. “Through the pantries and the kitchens where the French are. The French will not betray us… even if they see us. We can rely on their friendship.”

With wildly beating hearts they crept down the narrow staircase, through the kitchens and underground passages to one of the pantries, the door of which opened onto the burial ground.

Darnley gasped. “Not that way!” he cried.

“Where else?” demanded Mary contemptuously. “Will you come or will you stay behind to share David’s fate?”

Darnley still hesitated, his face deathly pale in the moonlight. He was terrified of going on, yet he had no alternative but to follow her, and as he stumbled forward he all but fell into a newly made grave.

He shrieked, and Mary turned to bid him be silent.

“Jesus!” she cried, looking down into the grave. “It is David who lies there.”

Darnley’s limbs trembled so that he could not proceed. “It’s an omen!” he whispered.

In that moment Mary seemed to see anew the terrified eyes of David as he had been dragged across the floor. Angrily she turned on her husband: “Mayhap, it is,” she said. “Mayhap David watches us now… and remembers.”

“No… no,” groaned Darnley. “’Twas no fault of mine.”

“This is not the time,” said Mary, turning and hurrying forward.

He followed her across the grisly burial ground, picking his way between the tombs and shuddering as he caught glimpses of half-buried coffins.

On the far edge of the burial ground Erskine was waiting with horses. Silently they mounted, Mary riding pillion with Erskine.

“Make haste!” cried Darnley, now longing above all things to put as great a distance as possible between himself and the grim graveyard. He imagined David’s ghost had been startled from his grave and caused him to stumble there. Terror overwhelmed him—terror of the dead and of the living.

They rode on through the quiet night, but Erskine’s horse with its royal burden could not make the speed which Darnley wanted.

“Hasten, I say!” he cried impatiently. “’Tis dangerous to delay.”

“My lord, I dare not,” said Erskine.

“There is the child to consider,” cried Mary. “We go as fast as is safe for it.”

“They’ll murder us if they catch us, you fools!” cried Darnley.

“I would rather be murdered than kill our child.”

“In God’s name that’s folly. What is one child? If it should die this night, there’ll be others to replace it. Come on, man. Come on, I say. Or I’ll have you clapped in jail as soon as we are out of this.”

Mary said: “Heed him not. I would have you think of the child.”

“Yes, Madam,” said Erskine.

Darnley shouted: “Then tarry and be murdered. I’ll not.”

And with that he whipped up his horse and went ahead with all speed, so that soon he was lost to sight.

Mary felt the tears smarting in her eyes, but they were tears of shame for the man she had married. She was not afraid anymore. In moments such as this one, when she was threatened with imminent danger, she felt a noble courage rise within her. It was at such times that she felt herself to be a queen in very truth. She had duped Darnley; she had lured him to desert her enemies. She had foiled the plots of Moray and the scheming Morton. Once again, she believed, she had saved her crown.

Oh, but the humiliation of owning that foolish boy for a husband! For that she could die of shame. He was not only a fool; he was a coward.

How she wished that he could have been a strong man, a brave man on whom she could rely. Then she would not have cared what misfortunes befell them; they would have faced them and conquered them together.

After many hours in the saddle, just as the dawn was breaking, Erskine called to her that they could not be far from the safety of Dunbar Castle.

A short while after, he told her that he saw riders. Mary raised her weary eyelids. One man had ridden ahead of the rest. He brought his horse alongside that which carried the Queen. She looked with relief and admiration at this man who reminded her, by the very contrast, of the husband whom she despised.

She greeted him: “I was never more glad to see you, Lord Bothwell.”