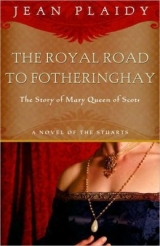

Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Lord James was disturbed. It was a charming gesture, charmingly made, and it might be that she did right to make it at that moment. But as his eyes met those of Maitland of Lethington he knew that the great diplomat agreed with him that Mary Stuart would find trouble in Scotland. The Kirk—and its leader, John Knox—would find good cause to quarrel with her, and the Kirk and John Knox wielded great power in Scotland.

DUSK HAD FALLEN before Mary reached her capital city and, as it grew dark, she had the pleasure of seeing the bonfires flare up, first on Cal ton Hill, then on Salisbury Crag; she saw them burning in the city itself and she could hear the shouts of the people. It was comforting; their welcome might be rough according to French standards, but it was at least a genuine welcome.

Now she could see the fortress which had been built by her father. It looked dark, even menacing. She gazed uneasily at its towers and their crenelated battlements.

Here she would rest, just outside the city’s walls; for clearly she could not make her triumphal entry into her capital in darkness.

It was a vast and noble palace, but it seemed chill and without comfort. The few tapestries which hung on the walls lacked the brilliance and beauty of those to which she was accustomed; here were no delicate carpets, no carved furniture; everything was plain, heavy and sparse.

Mary had been warmed by the loyal shouts of the mob which had accompanied her to the palace, and soon she would have some of her cherished possessions about her; she would bring warmth and cheer to the place; so that a little discomfort now seemed of small account. She could endure anything, she believed, provided she had the love and loyalty of her people. Even now she could hear the people from the city, crowding about the walls of the palace and calling: “God Save the Queen!”

Tired as she was, in need of a hearty meal and the comfort she had known at the Court of France, she was not unhappy.

She found Flem beside her. Flem seemed touched with a glowing excitement; she had not noticed before that Flem was growing into a real beauty. Mary noticed also that the stern Lord Maitland had his eyes on Flem, although he was doubtless old enough to be her father.

That served to remind her that now they were home there would necessarily be a few marriages in her suite. She was going to enjoy bringing happiness to those she loved. There would certainly be other marriages to consider besides her own.

Dear Flem! She was not indifferent to the admiring glances of that important statesman. Mary would tease her about it tomorrow.

The meal was served and it seemed more tasty than it was, so hungry were they. And when it was over Mary retired to the apartment which had been prepared for her. While her Marys helped her to disrobe she talked excitedly of the way in which they would refurnish these apartments. It seemed to her then that the nostalgic melancholy of the first day and night had diminished a little. They were not in love with their new life—any of them—but they were becoming reconciled to it.

Then suddenly there broke out beneath her window what seemed to them a caterwauling, a barrage of the harshest sounds they had ever heard. Mary started up in horror, and hastily caused herself to be robed once more. Just as Flem and Livy were fastening her gown, and as the noise had grown louder and wilder and more discordant, there was a knocking on the door of the apartment.

It was Lord James with Lord Maitland, Marys three Guise uncles and d’Amville.

“What has happened?” cried Mary in alarm. “Is someone being murdered?”

“The loyal citizens of Edinburgh have come to give you welcome,” said Lord James dryly. “They are playing the bagpipes in your honor. It would be well for you to appear at your window and say a few words of gracious thanks to them.”

“And,” said Elboeuf in rapid French, “mayhap that will have the desired effect of putting an end to such earsplitting sound.”

Mary, listening, began to detect the stirring music in what had at first seemed harsh to her, and she felt angry with those Frenchmen who put their hands over their ears. This was bad manners. To those people below, the old Scottish airs and melodies were sweet music and intended to be a tribute to her.

The bagpipes were subdued as those outside the palace walls began to sing.

“But what sad songs!” cried Mary. “It would seem as though they were sorry that I have come. They can hardly be songs of rejoicing.”

“They are the hymns of the Kirk,” said Lord James solemnly.

“Hymns!” cried the irrepressible Elboeuf. “At such a time! I should have thought sweet madrigals or happy songs expressing joy at the Queen’s return would have been more suitable.”

“The people of Edinburgh thank God that the Queen has returned, and they do so sincerely and solemnly. They have been taught that it is sinful to sing profane songs. The Kirk does not allow it.”

“But for the Queens homecoming …”

“They wish to greet her in a God-fearing way.”

Elboeuf lifted his shoulders. He was already homesick for Paris and Lorraine. D’Amville and his friend Chastelard were looking at the Queen, and their looks said: “This is a strange and barbarous country, but we rejoice to be here since you are.”

And while most of the French put their hands to their ears, trying to shut out the sounds, Mary went to a window and cried: “I thank you all, good people. I thank you with all my heart. You have delighted me with your loyal greetings and I rejoice to be among you.”

The people cheered and shouted. The solemn singing of hymns continued far into the night, and the pipes kept up their stirring strains until far into the morning.

FROM THE WINDOWS of Holyroodhouse Mary could look on her capital city. She could see the High Street—the neatest and cleanest in the world—with its stone flags and the channels on either side, made to drain off the rain and filth, and the stone houses with their wooden galleries. There stood the Tolbooth Prison, and as she looked at it she swore none should be incarcerated there during her reign merely for wishing to masque and enjoy laughter; she could see the Lawnmarket and the noble houses and gardens of the Canongate which led to Holyrood.

The great Tron stood in the center of Market Cross, and there were the stocks and pillories. This was the busiest spot in all Edinburgh, and here, during the days which followed the arrival of the Queen, the people gathered to talk of all that her coming would mean. Apprentices from the goldsmiths’ shops in Elphinstone Court, tinsmiths from West Bow, and stallholders from the Lawnmarket all congregated there in Market Cross to discuss the Queen; and when they discussed the Queen they remembered that other who had told them—and the world—that he was her enemy: the man whom they flocked to hear in the Kirk, the man who swayed them with his promises of salvation and—more often—his threats of eternal damnation.

John Knox ruled the Kirk, and the Kirk was ruling Scotland. Preaching armed resistance to the Devil—and the Devil was everyone who did not agree with John Knox—he had on more than one occasion stirred the people of Scotland to rebellion. With his “First Blast against the Monstrous Regiment of Women” he had told the world of his contempt for petticoat government, although now that Elizabeth was on the throne of England and promising to do much good for the cause which was John Knox’s own, he wished that he had been a little more cautious before publishing his “First Blast.” He was a cautious man for all his fire. He believed God spoke through him; he believed he owed it to the world to preserve himself that he might the better do God’s work. For this reason he had often found it necessary to leave Scotland when his person might be in danger. “All in God’s service,” he would say from the safety of England or Geneva. “I take a backseat for the better service of God.”

In his absence his actions might be questioned, but when the people saw again the fanatical figure with the straggling beard streaming over his chest like a Scottish waterfall, and heard his wildly haranguing voice, they were converted once more to their belief not only in the reformed religion but in the sanctity of John Knox.

“Have you heard Knox’s latest sermon?” was the often-repeated question.

They had. They would not have missed it for all the wealth of Holyroodhouse.

Knox was setting himself against the Queen as he had set himself against her mother. He had preached against the Devil’s brood and the congregation of Satan. This included the Queen. Had he not prayed to God to take her mother, declaring to his congregation, when she was smitten with the dropsical complaint which eventually killed her: “Her belly and loathsome legs have begun to swell. Soon God in His wisdom will remove her from this world”? Had he not rejoiced openly in the Kirk when she had died? Had he not laughed with fanatical glee when he had heard of the death of Mary’s husband? “His ear rotted!” cried John Knox. “God wreaked Divine Vengeance on that ear which would not listen to His Truth.”

John Knox was no respecter of queens; he would rail against the new one. He would do his utmost to rouse the people against her; unless she cast aside her religion and took to his, he would work unceasingly for her defeat and death as he had worked for her mothers.

The French in the palace were inclined to laugh at the preacher; but Mary did not laugh. The man alarmed her, although only slightly as yet. She looked to those two statesmen, her brother James and Lord Maitland, to help and guide her in what she had to do, although she reminded them that when she had come home she had made no bargain to change her religion. She was a Catholic and would always be so. She would, she said, try to show this man the way of tolerance.

Lord James nodded. He was determined that his sister should leave the government of the country to him and Maitland. They were Protestants, but of a different kind from Knox. Religion was not the whole meaning of their existences; it was something with which to concern themselves when more important matters were not at issue. Maitland and Lord James, while agreeing that a happier state of affairs might have existed had the Queen adopted the religion of the majority of her subjects, were quite prepared to let her celebrate Mass in her own chapel.

Mary, characteristically, wished now to concentrate on what was pleasant rather than unpleasant. She renewed her acquaintance with two more of her half brothers—John and Robert—handsome, merry boys, slightly older than herself, and she loved them both.

Some of the furnishings had been sent from Leith, and it was a pleasure to set them up in her apartments. The lutes and musical instruments had arrived, so the Court was now enjoying music in the evenings. Mary herself sang and danced under the admiring gaze of many, including d’Amville and Chastelard.

The people of Edinburgh had shown themselves delighted with her youth and beauty. She looked as a queen should; she always had a smile of warm friendliness, and the men whose lives she had saved on the way from Leith to Edinburgh talked of her beauty and wisdom and how, in their belief, she would bring great happiness to her country.

Mary had much to learn of the bitterness and venom which always seemed to attach themselves to religious differences. It did not occur to her that there could be any real reason why she should not continue in her mode of worship, while any of her subjects who wished to follow a different doctrine should do so.

Knox, according to her uncles and d’Amville, was something of a joke, and she did not take him very seriously until her first Sunday in Holyrood Palace. That day she announced her desire to hear Mass in the chapel and, dressed in black velvet and accompanied by her Marys, she was making her way there when she heard the sounds of shouts and screams.

Chastelard came running to her and begged her not to proceed.

“Your Majesty, the mob is at the gates of the Palace itself. They have been inflamed by the man Knox. They swear they will not have the Mass celebrated in their country.”

Mary’s temper—always quick—flared up at once. She had intended to play a tolerant role with her people; she was infuriated that they should attempt to do otherwise with herself.

“The mob!” she cried. “What mob?”

“Knox’s congregation. Listen, I beg of you. They are in an ugly mood.”

“I, too, am in an ugly mood,” retorted Mary; but she listened and heard the cries of “Satan worship! Death to the idolators!”

Flem had caught one of her arms, Seton the other. Mary threw them off angrily, but Chastelard barred her way.

“At the risk of incurring Your Majesty’s displeasure, I cannot allow you to go forward.”

She laid her hand on the young man’s arm and her anger melted a little as she caught the ardor in his eyes, but she was not going to be turned from her anger. She pushed him aside, but even as she started forward, she saw two men bringing back her priest and almoner. There was blood on their faces.

She ran to them in consternation. “What have they done to you?”

The almoner spoke. “It was little, Your Majesty. They wrenched the candlesticks from us and laid about them. But Your Majesty’s brothers were at hand, and Lord James is speaking to the people now.”

She hurried on. Lord James was addressing the crowd which had gathered about the door of the chapel.

The crowd would stand back, he ordered. None should come a step nearer to the chapel on pain of death. He himself, Lord James Stuart, would have any man answer with his life who dared lay hands on the Queen or her servants.

There was a hush as Mary approached.

James said to her: “Say nothing. Go straight into the chapel as though nothing has happened. There must be no trouble now.”

There was something in James’s manner which made her obey him. Trembling with indignation, longing to turn and try to explain to these people why she followed the Church of Rome, yet she obeyed her brother. He seemed so old and wise, standing there, his sword drawn.

He sent Chastelard back to bring the priest and almoner, that they might celebrate Mass in the chapel according to the Queens wishes; and after a while Mary was joined by the priest and the almoner, their bandaged heads still bleeding from their wounds.

Mass was celebrated; but Mary was aware of the mob outside. She knew that, but for the fact that her brother stood there to protect her, the crowd would have burst into the chapel.

SHE SAT WITH her brother in her apartments. Lord Maitland was with them.

She was perusing the proclamation, addressed to the citizens of Edinburgh, which was to be read in Market Cross.

“There,” she said, handing the scroll to James, “now they will understand my meaning. They will see that I do not like this continual strife. I am sure that with care and tolerance I, with my people, shall find a middle way through this fog of heresies and schisms.”

Maitland and Lord James agreed with the wording of the document. It was imperative to Lord James’s ambition that his sister should continue as nominal Queen of Scotland, for the downfall of Mary would mean the downfall of the Stuarts. It was necessary to Maitland that Mary should remain on the throne, for his destiny was interwoven with that of Lord James. They wished for peace, and they knew that the father and mother of war were religious controversy and religious fanaticism.

The proclamation was delivered in Market Cross and then placed where all who wished to could read it.

The citizens stood in groups, discussing the Queen and her Satan worship, or John Knox and his mission from God. To most men and women tolerance seemed a good thing, but not so to John Knox and the Lords of the Congregation. Mary was the “whore of Babylon” declared the preacher and “one Mass was more to be feared than ten thousand men-at-arms.” “My friends,” he shouted from his pulpit, “beware! Satan’s spawn is in our midst. Jezebel has come among us. Fight the Devil, friends. Tear him asunder.”

After that sermon Maitland declared to the Lord James and the Queen that nothing but a meeting between her and Knox could satisfactorily bring them to an understanding.

Mary was indignant. “Must I invite this man… this low, insolent creature … to wrangle with me?”

“He is John Knox, Madam,” said Lord James. “Low of birth he may be, but he is a man of power in this country. He has turned many to his way of thinking. Who knows, he may influence Your Majesty.”

Mary laughed shortly.

“Or,” added the suave Maitland, “Your Majesty may influence him.”

It was a strange state of affairs, Mary said, when men of low birth were received by their sovereign simply because they ranted against her.

The two men joined together in persuading her.

“Your Majesty must understand that, to the people of Scotland, John Knox’s birth matters little. He himself has assured them of that. With his fiery words he has won many to his side. Unless you receive the reformer, you will greatly displease your subjects. And you will weaken your own cause because they will think you fear to meet him.”

So Mary consented to see the man at Holyrood, and John Knox was delighted to have a chance of talking to the Queen.

“Why should I,” he asked his followers, “fear to be received in the presence of this young woman? They say she is the most beautiful princess in the world. My friends, if her soul is not beautiful, then she shall be as the veriest hag in my eyes, for thus she will be in the eyes of God. And shall I fear to go to her because, as you think, my friends, she is a lady of noble birth, and I of birth most humble? Nay, my friends, in the eyes of God we are stripped of bodily adornments. We stand naked of earthly adornment and clothed in truth. And who do you think, my friends, would be more beautiful in the eyes of God? His servant clothed in the dazzling robes of the righteous way of life, or this woman smeared with spiritual fornications of the harlot of Rome?”

So Knox came boldly to Holyroodhouse, his flowing beard itself seeming to bristle with righteousness, his face bearing the outward scars of eighteen months’ service in the galleys, which into his soul had cut still deeper. He came through the vast rooms of the palace of Holyrood, already Frenchified with tapestry hangings and fine furniture, already perfumed, as he told himself, with the pagan scents of the Devil, and at length he faced her, the dainty creature in jewels and velvet, her lips, hideously—he considered—carmined and an outward token of her sin.

She disturbed him. In public he railed against women, but privately he was not indifferent to them. In truth, he preferred their company to that of his own sex. There was Elizabeth Bowes, to whom he had been spiritual adviser, and with whom he had spent many happy hours talking of her sins; it had been a pleasure to act as father-confessor to such a virtuous matron. There had been Marjorie, Elizabeth’s young daughter, who at sixteen years of age had become his wife, and who had borne him three children. There was Mistress Anne Locke, yet another woman whose spiritual life was in his care. He railed against them because they disturbed him. These women and others in his flock were ready to accept the role of weaker vessels; it was pleasant to sit with them and discuss their sins, to speak gently to them, perhaps caress them in the manner of a father-confessor. Such women he could contemplate with pleasure as his dear flock. He and God—and at times he assumed they were one—had no qualms about such women.

But the Queen and her kind were another matter. Every movement she made seemed an invitation to seduction; the perfume which came from her person, her rich garments, her glittering jewels, her carmined lips were outward signs of the blackness of her soul. They proclaimed her “Satan’s spawn, the Jezebel and whore of Babylon.”

There were other women in the room, and he believed these to be almost as sinful as the Queen. They watched him as he approached the dais on which the Queen sat.

Lord James rose as he approached.

“Her Majesty the Queen would have speech with you.”

Mary looked up into the fierce face, the burning eyes, the belligerent beard.

“Madam—” he began.

But Mary silenced him with a wave of her hand.

“I have commanded you to come here, Master Knox, to answer my questions. I wish to know why you attempt to raise my subjects against me as you did against my mother. You have attacked, in a book which you have written, not only the authority of the Queen of England, but of mine, your own Queen and ruler.” He was about to speak, but yet again she would not allow him to do so. “Some say, Master Knox, that your preservation—when others of your friends have perished—and your success with your followers are brought about through witchcraft.”

A sudden fear touched the reformer’s heart. He was not a brave man. He believed himself safe in Scotland at this time, but witchcraft was a serious charge. He had thought he had been brought here to reason with a frivolous young woman, not to answer a charge. If such a charge was to be brought against him, it would have been better for him to have taken a trip abroad before the new Queen came home.

“Madam,” he said hastily, “let it please Your Majesty to listen to my simple words. I am guilty of one thing. If that be a fault you must punish me for it. If to teach God’s Holy word in all sincerity, to rebuke idolatry and to will the people to worship God according to his Holy Word is to raise subjects against their princes, then I am guilty. For God has called me to this work, and he has given me the task of showing the people of Scotland the folly of papistry, and the pride, tyranny and deceit of the Roman Anti-Christ.”

Mary was astounded. She had expected the man either to defend himself or to be so overcome by her charm that he would wish to please rather than defy her.

He went on to talk of his book. If any learned person found aught wrong with it, he was ready to defend his opinions, and should he be at fault he was ready to admit it.

“Learned men of all ages have spoken their judgments freely,” he said; “and it has been found that they were often in disagreement with the judgment of the world. If Scotland finds no inconvenience under the regiment of a woman, then I shall be content to live under your rule as was St. Paul under Nero.”

His comparisons were decidedly discomfiting. Not for a moment would he allow any doubt to be cast on his role of saint and God’s right-hand man, and hers as tyrant and sinner.

“It is my hope, Madam, that if you do not defile your hands with the blood of saints, neither I nor what I have written may do harm to you.”

“The blood of saints!” she cried. “You mean Protestants, Master Knox. Your followers stained their hands with the blood of my priest only last Sunday. He did not die, but blood was shed.”

“I thank God he did not die in the act of sin. There may yet be time to snatch his soul for God.”

Thereupon the preacher, seeming to forget that he was in the Queens Council Chamber, began to deliver a sermon as though he were in a pulpit at the Kirk. The fiercely spoken words rolled easily from his tongue. He pointed out how often in history princes had been ignorant of the true religion. What if the seed of Abraham had followed the religion of the Pharaohs—and was not Pharaoh a great king? What if the Apostles had followed the religion of the Roman emperors? And were not the Roman emperors great kings? Think of Nebuchadnezzar and Darius….”

“None of these men raised forces against his prince,” said Mary.

“God, Madam, had not given them the power to do so.”

“So,” cried Mary aghast, “you believe that if subjects have the power, it is right and proper for them to resist the crown?”

“If princes exceed their bounds and do that which God demands should be resisted, then I do, Madam.”

She was furious with him for daring to speak to her as he had; she felt the tears of anger rising to her eyes; she covered her face with her hands to hide those tears.

Knox went on to talk of the communion with God which he enjoyed, of his certainty that he was right and all who differed from him were wrong.

James was at the Queen’s side. “Has aught offended you, Madam?” he asked.

She tried to blink away her tears, and with a wry smile said: “I see that my subjects must obey this man and not me. It seems that I am a subject to them, not they to me.”

The reformer turned pale; he read into that speech an accusation which could carry him to the Tolbooth. He was off again, explaining that God asked kings and queens to be as foster parents to the Church. He himself did not ask that men should obey him… but God.

“You forget,” said Mary, “that I do not accept your Church. I find the Church of Rome to be the true Church of God.”

“Your thoughts, Madam, do not make the harlot of Rome the immaculate spouse of Jesus Christ.”

“Do yours set the Reformed Church in that position?”

“The Church of Rome, Madam, is polluted.”

“I do not find it so. My conscience tells me it is the true Church.”

“Conscience must be supported by knowledge, Madam. You are without the right knowledge.”

“You forget that, though I am as yet young in years, I have read much and studied.”

“So had the Jews who crucified Christ.”

“Is it not a matter of interpretation? Who shall be judge who is right or wrong?”

Knox’s answer was: “God!” And by God he meant himself.

Mary’s eyes appealed to her brother: Oh, take this man away. He wearies me.

John Knox would not be silenced. There he stood in the center of the chamber, his voice ringing to the rafters; and everything he said was a condemnation, not only of the Church of Rome, but of Mary herself.

For he had seen her weakness. She was tolerant. Had she been as vehement as he was, he would have spoken more mildly, and he would have seized an early opportunity to leave Scotland. But she was a lass, a frivolous lass, who liked better to laugh and play than to force her opinions on others.

Knox would have nothing to fear from the Queen. He would rant against her; he would set spies to watch her; he would put his own interpretation on her every action, and he would do his utmost to drive her from the throne unless she adopted the Protestant Faith.

Mary had risen abruptly. She had glanced toward Flem and Livy, who had been sitting in the window seat listening earnestly and anxiously to all that had been said. The two girls recognized the signal. They came to the Queen.

“Come,” said Mary, “it is time that we left.”

She inclined her head slightly toward Knox and, with Flem and Livy, passed out of the room.

BY THE LIGHT of flickering candles the Queen’s apartment might well have been set in Chenonceaux or Fontainebleau. She was surrounded by her ladies and gentlemen, and all were dressed in the French manner. Only French was spoken. From Paris had come her Gobelins tapestry, and it now adorned the walls. On the floor were rich carpets, on the walls gilt-framed mirrors. D’Amville and Montmorency were beside her; they had been singing madrigals, and Flem and Beaton were in an excited group who were discussing a new masque they intended to produce.

About the Court the Scottish noblemen quarreled and jostled for honors. The Catholic lords sparred continually with the Protestant lords. On the Border the towns were being ravished both by the English and rival Scottish clans.

In the palace were the spies of John Knox, of Catherine de Médicis and of Elizabeth of England. These three powerful people had one object: to bring disaster to the Queen of Scots.

Yet, shut in by velvet hangings and Gobelins tapestry, by French laughter, French conversation, French flattery and charm, Mary determined to ignore what was unpleasant. She believed her stay there would be short; soon she would make a grand marriage—perhaps with Spain. But in the meantime she would make it pass as merrily and in as lively a fashion as was possible; and so during those weeks life was lived gaily within those precincts of Holy rood which had become known as “Little France.”