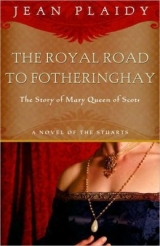

Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

THREE

IN THE VAST ROOM AT SAINT-GERMAIN THE CHILDREN OF the royal household were assembled as was their custom at this hour.

In a window seat sat Mary—one of the eldest and certainly the most beautiful. She was holding court as she loved to do. Monsieur du Bellay was reading one of his poems, and those who gathered about her—among them Ronsard and Maison-Fleur, those great Court poets—knew that it had been written for her.

“Contentez vous, mes yeux,

Vous ne verrez jamais une chose pareille.”

Ronsard and du Bellay had been the leaders of that coterie which called itself the Pleïade after a group of seven ancient Greek poets, and had been chosen by Marguerite, the King’s sister, to be literary tutors of the royal children and those young people who shared the nursery. Their favorite pupil was Mary, not only on account of her beauty which inspired them to lyrical verse, but because of her response to their own work and of that literary talent which she herself possessed.

All eyes were on her now. François the Dauphin openly admired her, and he was anxious that all should remember she was to be his bride. His brother Charles, though only seven years old, was already one of Mary’s admirers. There was also Henri de Montmorency, the second son of Anne, the great Constable, and he could not take his eyes from her face.

Mary was content at such times. She needed such adulation. The last six years of her life had not been easy; Madame de Paroy was still with her and had turned out to be all that Mary feared. Mean-spirited, she lost no time in reporting the least misdemeanor, and she and the Queen never allowed the smallest error to go unpunished. Mary had been made to understand that she was as subject to discipline as any of the other children. She had been chastised as they had; but she had suffered far more from the loss of her dignity than from any physical pain.

In vain had she tried to rid herself of the woman. She had implored her mother to appoint a new governess; her uncle, the Cardinal, realizing the woman to be a spy of the Queen of France, had added his pleas to Mary’s, but in this matter Catherine stood firm, and neither the King nor Diane cared to interfere in a situation which had come about through the indiscretion of the King.

Lady Fleming had never returned to France, although her son remained to be brought up as a royal child; he was often in the nurseries, a bright, intelligent boy who quickly won his father’s affection. But Janet had had to take up her residence in Scotland.

So, at such times as this one when she could escape from the supervision of Madame de Paroy, Mary was happy, with François her constant companion and Charles showing his affection for her. She wished that Charles were not so wild and would grow out of those unaccountable rages of his. When they were on him he would suddenly kick walls, his dogs or his servants, whichever happened to be at hand. It was disconcerting. But she loved both brothers with a deep protective love. That did not mean that she was not becoming increasingly aware of the ardent looks sent in her direction by young Henri de Montmorency.

There were so many people at the Court to tell her how lovely she was. Monsieur Brantôme, the writer, assured her that her beauty radiated like the sun in the noonday sky. Her uncle, François, Duc de Guise, the great soldier and idol of Paris, exclaimed when he saw her: “By the saints! You are the fairest creature in France!” Uncle Charles, the Cardinal of Lorraine, held her face in his beautiful scented hands and looked long into her eyes, declaring: “Your beauty will charm all France!” The King himself whispered to her that she was the loveliest of his daughters; and it seemed that all men were ready to sing the praises of Mary Stuart. Lately, devoted as she was to her dear François, she had begun to wish that he looked a little more like Henri de Montmorency.

There were now thirty children in the royal nurseries, for many of the sons and daughters of noble houses were being brought up there. It was a world in itself consisting of ten chamberlains, nine cellarers, thirty-seven pages and twenty-eight valets de chambres, besides doctors, surgeons, apothecaries and barbers. The amount of food consumed by this community each day was prodigious. Twenty-three dozen loaves were baked each morning and eaten before nightfall; eight sheep, four calves, twenty capons as well as pigeons, pullets, hares and other delicacies went the same way. The Dauphin and Mary had in addition their separate establishments with a further retinue of servants, but much of their time was spent in these main apartments.

The family of royal children had grown considerably since Mary had first come to France. These children were scattered about the room now.

Twelve-year-old Elisabeth and her sister Claude who was slightly younger were in Mary’s group. Poor little Louis had died seven years ago and Charles was now the boy next in age to François. There was young Henri, who had been christened Edouard Alexandre but was always called Henri by his mother. He had just passed his sixth birthday and was extraordinarily handsome, with dark flashing eyes and the features of his mother’s Italian ancestors. He was the only one of the children whom Queen Catherine spoiled, and consequently he was very vain. Mary watched him displaying the earrings he was wearing.

There was little Marguerite, whom Charles had nicknamed Margot, precocious and vivacious and looking older than her five years; and lastly Hercule, the baby, a pretty, chubby boy of three.

Pierre de Ronsard was sitting beside her; he saw that her attention was wandering as she surveyed the children.

“Since Monsieur du Bellay’s verses do not interest Your Majesty, may I read some of mine?” he asked.

Mary held up her hand, laughing. “No more verses just now please. Let us talk of you. Tell us of your early life and how, with your friends, you formed that group of poets called the Pleïade”

They gathered round while Ronsard told, in his clever and amusing way, of the Court of Scotland whither he had gone long before the birth of Mary, when her fathers first wife had arrived from France.

He told how one day he had discovered a gentleman of the Court reading a small volume, how he had taken it, and once he had experienced the magic of those pages he had known that his life would be barren if it were not devoted to literature. He told of Cassandre, the woman he had loved; he quoted the sonnets he had written to her. He went on to speak of his life in the house of Jean Antoine Baïf where there was great poverty but greater love of literature.

“We were worshipers in the temple of literature. It mattered not that we were cold and hungry. It mattered not that we shared one candle between us. We studied Greek and Latin, and literature was food and drink to us—our need and our pleasure. Then we discussed our great desire to make France the center of learning. We would enrich France; we would make her fertile. Literature was the gentle rain and the hot sun which would ripen the seed and give us a rich harvest. So we formed the Pléiade—seven of us—and with myself, du Bellay and Baïf as the leaders, the Pléiade was to shine from the heavens and light all France.”

Henri de Montmorency had moved closer to Mary.

His passionate eyes looked into hers.

“Would it were possible to speak with you alone!” he whispered.

SHE DID meet him alone. She had wandered through the gardens of Fontainebleau, through the great courtyard and past the fountains, and had made her way to the walled garden.

Then she saw Henri de Montmorency approaching her. He was the second son of the great Constable of France whom the King loved and who, to his great grief, had been captured by the Imperial troops at the defeat of Saint Quentin and now lay a prisoner of Philip of Spain. How handsome he was, this Henri; he was so elegant in satin and velvet, the colors of which—pink and green—blended so perfectly. The jewels he wore had been carefully chosen. Henri de Montmorency—one of the most favored young men of the Court because his father had been, and doubtless would be again, one of the most powerful—was a leader of fashion and good taste.

“Your Majesty!” He took Mary’s hand and raised it to his lips. The eyes he lifted to hers were ardent.

She had no wish for such love as she believed was customary throughout the palaces of Fontainebleau, Blois, Amboise, Chambord, or anywhere the Court happened to be. The love which François the Dauphin had for her was the love she wished for. She enjoyed the love of the poets—idealistic and remote; she enjoyed the ardent admiration of Charles. There was, also, the strange and somewhat mystic love which her uncle, the Cardinal of Lorraine, bore her. Those caressing hands which seemed to imply so much, those queer searching looks, those lingering kisses, that spiritual love as he had described it, disturbed her; it frightened her too, but she was child enough to enjoy being a little frightened. She was always afraid, when she was with the Cardinal, that his love for her would change and become something wild and horrible; she fancied that he too was conscious that it might, and that he took a delight in holding his passion on a leash which he would, from time to time, slacken so that it came near to her and yet did not quite reach her. She could not imagine what would happen if it did, but something within her told her that it never would because the Cardinal did not wish it; and in all things the Cardinal’s will was hers.

All these loves were different from the love of ordinary mortals; pawing, kissing, giggling and scuffling she would not have. She was a queen and would be treated as such.

Yet here was Henri de Montmorency, beautiful as she herself was beautiful, young as she herself was young, and offering yet another sort of love, a charming and romantic idyll.

“I saw you enter the garden,” he said breathlessly. “I could not resist following you.”

“We should not be here alone, Monsieur de Montmorency.”

“I must see you alone sometimes. Sometimes we must do that which is forbidden. Does not Your Majesty agree?”

“It is wrong to do that which is forbidden.”

“Can we be sure of that? I am happier now than I have been since I first set eyes on you.”

“But I do not think you should speak thus to me, Monsieur de Montmorency.”

“Forgive me. I speak thus out of desperation. I adore you. I must let you know of my feelings. Many love you, but none could do so with more passion, with more devotion and more hopelessness than your devoted servant Henri de Montmorency.”

He took her hands and kissed them with passion. She tried to withdraw them for she was conscious of emotion never before experienced, and she was afraid. She could not help comparing him with François. I am being disloyal to dear François! she thought in dismay.

“You are not indifferent to me!” cried Henri.

“We should return to the palace,” said Mary uneasily.

“Just a few more moments, I beg of you. I love you and I am wretched because shortly I must see you married to the Dauphin.”

“That must not make you miserable. It is my destiny, and doubtless you have yours.”

“My father, when he returns, will seek to marry me with the granddaughter of Madame de Valentinois. Oh, how wretched is this life! We are counters to be moved this way and that, and our loves and our desires go for naught. You will be married to the Dauphin. Your destiny is to be Queen of France and I… mine is a lesser one, but I am to ally my house with that of the King’s mistress. I wish we could run away from France … to some unknown island far away from here…. Would you were not a queen! Would I were not the son of my father! If you were a peasant girl and I a poor fisherman, how much happier we might be!”

Mary could not imagine herself stripped of her royalty. She would never forget that she was a queen, she believed. But she was moved by his words and the eager devotion she saw in his eyes.

He went on bitterly: “My father has five sons and seven daughters and all must be used to favor the fortunes of our house. My elder brother loved a girl—deeply he loved her. He thought he would die of love, and for a long time he stood out against our fathers wishes. But now you see he is married to the Kings bastard daughter, Diane of France, and our house is made greater by alliance with the royal one. Now if I marry the granddaughter of Madame de Valentinois, I shall strengthen the link. Not only shall we be allied to the royal house but with that of the King’s mistress. What strength will be ours! What greatness! And all brought about because we have been moved as counters into the right squares on the board. They are flesh and blood, those counters; they cry out in anguish; but that is unimportant. All that matters is that our house grows great.”

“What are you saying, Monsieur de Montmorency?”

“That I would run away with you … far away… where all are merely men and women and there is no policy to be served, no great house that is of more moment than our happiness. Dearest Mary, if only we could run away together, far away from the kingdom of France where they will make you a queen, far away from that land where you are already a queen. Mary, did you know that in your country many of the nobles have signed the Solemn League and Covenant to forsake and renounce what they call the Congregation of Satan? That means they follow the new religion; they have cut themselves off from Rome. Yours will soon be a land of heretics. Oh, Mary, I see trouble there for you. You … a good Catholic… and Queen of a heretic land!”

“I know nothing of this,” she said.

“Then I should not have spoken of it.”

“I made my mother Regent of Scotland. I signed the documents some years ago.”

“Oh, Mary, they tell you what to sign and what not to sign. They tell you to marry and you marry. Oh, dearest and most beautiful, let us dream just for a moment of the impossible. Do you love me … a little?”

She was excited by his charm and the wild words he spoke. She was happy in this scented garden. But she knew she should not listen to him and that she could never be happy if she were disloyal to François. She turned away frowning.

“I see,” he said bitterly, “that they have molded you as they wished. You will be their docile Queen. You will sign the documents they put before you; you will sign away your life’s happiness when they ask it.”

“When I am the wife of François,” she said angrily, “I shall be assured of a lifetimes happiness, Monsieur.”

She turned to leave him and as she did so she saw that two people had entered the garden. The rich red robes of the Cardinal of Lorraine were brilliant beside the more somber garments of Queen Catherine.

Mary heard the sudden burst of laughter which she had grown to hate over the years. Catherine’s amusement was, she believed, invariably provoked at someone else’s discomfiture.

“Ah, Cardinal, our birds are trapped,” the Queen was saying. “And what pleasant-looking birds, eh? We might say ‘birds of paradise.’ They look startled, do they not? As though they were about to be seized by the hawk.”

“Or by the serpent, Madame,” said the Cardinal.

“Poor creatures! What hope of escape would they have between the two!”

“Very little, Madame. Very little.”

Mary and Montmorency had hurried forward to pay their respects, first to the Queen, then to the Cardinal.

The Queen said: “So you two charming people are taking the air. I marvel, Monsieur de Montmorency, that you do not do so in the company of another young lady… not the Queen of Scotland. And I should have expected to see my son with her Scottish Majesty.”

“We met by chance, Madame,” said Mary quickly, but the color rose to her cheeks.

The Cardinal was looking at her quizzically. Because he had made her aware of those occasions when she caused him displeasure, she knew now that he was far from pleased at discovering her thus.

As for the Queen, she was delighted. Mary sometimes thought that the Queen did not wish her to marry the Dauphin, and that she would be very pleased if Mary had been seriously attracted by Montmorency.

The Cardinal said: “Her Majesty and I, as you no doubt did, found the afternoon too pleasant to be spent with walls about us.”

Before Mary could answer, Catherine said: “The Queen of Scots appears to be in a fever.” Her long slender fingers touched Mary’s cheek. “You are overheated, my dear.”

“I have a headache. I was about to return to the cool of the palace.”

“Ah yes, the cool of the palace. That is the place for you. The bed, eh… with the curtains drawn, and no one to disturb you—that is the best remedy for the sort of fever which possesses your Scottish Majesty.”

Hating the insinuation contained in the Queens words, conscious of the discomfort of Henri de Montmorency and the displeasure of the Cardinal, Mary said impulsively: “Your Majesty has vast knowledge of such things. It is due to your keen observation of the conditions of others, rather than your experience of such maladies. But I dare submit you are mistaken on this occasion. It is a slight headache from the heat of the sun.”

The white hand, laden with rings, came down heavily on Mary’s shoulder. Mary winced under her grip.

“I am rarely mistaken,” said Catherine. “You are right when you speak of the keenness of my observation. Little can be hid from me. Now, Monsieur de Montmorency will escort you to the palace.” Catherine released Mary’s shoulder. “And do not forget my remedy. Your bed… the curtains drawn… the door locked to keep out your women. That is what you need. Go along… now. The Cardinal and I will continue our walk in the sunshine.”

Mary curtsied, Montmorency bowed, and the two walked back to the palace. As soon as possible Mary took leave of him and went to her apartments.

Flem and Beaton hurried to her anxiously, but she waved them aside. She had a headache; she would rest and she did not wish to be disturbed.

THE CURTAINS about Mary’s bed were silently withdrawn. Mary opened her eyes and saw, standing by the bed, the scarlet-clad figure of the Cardinal. She smelled the perfume of musk which accompanied him, and saw the glittering emeralds and rubies on his folded hands.

“Monsieur?” she cried, starting up.

“Nay, do not rise, my child,” he said; he sat on the bed and laid a hand on her hot forehead.

She lay back on her pillows.

“How lovely you are!” he murmured. “You are very beautiful, my dearest. But you are distressed now.”

“I… I came here to rest.”

“On the advice of Her Majesty!”

“I did not expect anyone would come in.”

“You would not have your guardian uncle kept out?”

“No… no… but…”

“Rest easily, my dear child. There is no need to be afraid. The Queen was right to suggest you should return to the palace. It is not good for one of your purity and budding beauty to be seen in intimate conversation with a young man of Montmorency’s reputation.”

“His… reputation!”

“Ah! You are startled. I see that you have more regard for this young man than I believed.”

“I did not know he had an evil reputation.”

“All young men have evil reputations.”

“That, Uncle, is surely not true.”

“Or they would,” went on the Cardinal, smiling, “if all their deeds and all their thoughts were known. They sport their jewels to show their worldly riches. What if they should wear their experiences to show their worldly wisdom, eh? Then our simple maidens might not so easily become their victims… their light-o’-loves to be discussed and dissected for their companions’ pleasure. Ah, you should hear the bawdy talk of some of these gallants when they are with others of their kind. You would be horrified. It is quite different from the sweet words which they employ as the prelude to seduction.”

“I will not be included among those simple maidens!”

“Indeed you shall not.” He slipped his arm under her and leaning forward, gazed into her face. He let his lips linger on her throat, and she felt her heart leap and pound. She could not move and it was as though she were bound by invisible cords. In his eyes there was a flame, in his arms a subtle pressure. Now he had unleashed this strange emotion which he had created; now it was about to envelop her. She was terrified, yet fascinated.

He was speaking softly. “Nay, you are no simple maiden, my dearest, my other self. My Mary, I love you as I have never loved anyone. Together we will explore the world of the spirit. You and I shall be as one, Mary, and together we will rule France.”

“I do not understand you….”

“You cannot expect to yet, but one day you will understand all that you are to me, and how I have preserved you and kept you sweet and pure.”

His mood had changed. The emotions were subdued. He sat up. He was smiling and his eyes were extraordinarily brilliant in his pale face.

“Mary,” he said, “in your bleak and savage country, I have heard, the men of the Border ravish towns and hamlets. They take the cattle; they take the women. And what do you think they do with these women? They rape them, Mary… in the village streets … on the village greens. They mock them. They insult and humiliate them in a hundred ways you cannot even imagine. That is your wild country; that is Scotland. Here we are supposed to be a civilized people. But are we? Some of these bejeweled gallants with their pretty looks and their flowery speeches, their odes to your beauty—they are very like your Borderers beneath their exquisite garments and their courtly manners. The Borderer rapes; our gallant seduces. The Borderer takes a woman as he would an apple; he discusses the flavor while he tastes. Our gallants pluck their apples in scented orchards; all is apparently decorous. But afterward, they discuss the flavor one with another. That is the difference between the Borderers of Scotland and our gallants. One, you might say, is at least candidly licentious; the other, under the cloak of gallantry, is full of deceit.”

“Why… why do you tell me this?”

“Because, ma mignonne, you are on the verge of womanhood. It is time you were honorably married. Holy Mother of God, your uncle François would run the young Montmorency through with his sword if he knew how he had insulted you in the gardens this day.”

“He did not insult me, Uncle. He was most chivalrous.”

“The first steps toward seduction, my dearest… the first indication that the scented couch is prepared. Even now we do not know that he will not boast of his success to his friends.”

“He dare not! He has nothing of which to boast.”

“The braggart will do very well on very little. I shall have him warned.

As for you, my dearest, you will not be seen in his company alone again. Do not let your manner change. Be friendly with him as you are with others. Only remember that he is another such as your Border raiders; remember that he is doing his utmost to lead you to seduction. Remember that he will note every weakness… any attention you may pay to his words. He will boast to his friends of an easy conquest, and we shall have them all trying to emulate him.”

Mary covered her burning cheeks with her hands.

“Please… Uncle… stop. I cannot bear such thoughts. It was nothing… nothing.”

The Cardinal kissed her forehead.

“My darling, I know it was nothing. Of course, it was nothing. My pure, sweet Mary, who shall remain pure and sweet for the heir of France.” He put his arm about her and held her against him. “If there should be one, other than the heir of France, it shall not be the son of the Constable!”

She caught her breath, for his lips were on hers. It was one of those moments when she sensed danger close. But almost immediately he had stood up and was smiling down on her.

“Rest, my beloved,” he said. “Rest and think on what I have told you.”

She lay still after he had gone, trying to shut out the thoughts which the Cardinal had aroused in her. She could not. She could no longer picture Henri de Montmorency as he had seemed to her that day in the gardens; he was a different person, laughing and leering, calling to others to come and see how he had humiliated the Queen of Scots.

She buried her face in her pillows trying in vain to shut out those pictures.

THE CARDINAL, deeply disturbed, sought out his brother.

“We must hurry on the marriage,” he said. “I am sure it is imperative that we should do so.”

The Duke looked grave. “With Mary so young and the Dauphin even younger…”

“There are two reasons which make it necessary for us to press the King until this marriage is accomplished. I have it from the Dauphin’s doctor that his health is failing fast. What if he were to die before Mary has married him?”

“Disaster!” cried the Duke. “Unless we could secure young Charles for her.”

“He’s nearly ten years younger, and it will be long before he is marriageable. No! Mary must be Dauphine of France before the year is out. I have another reason, brother. I saw her walking in the gardens with the son of our enemy.”

“That remark,” said François cynically, “might indicate the son of almost any man at Court. As our powers grow, so do our enemies. To which one do you refer?”

“Montmorency. The Queen was with me and I have an idea that she was delighted to see those two together. I fancy she tried to make more of the affair than was justified. She was quite coarse, and talked of a bed as the best place to cool Mary’s fever.”

“You alarm me, brother.”

“I mean to. There is reason for alarm. You are the hero of Paris, of all France. You have given back Calais to the King; you bear the mark of heroism on your cheek. The people look at the scar you bear there and cry: “Vive le Balafré!” At this moment you could demand the marriage, and the King would find it hard to refuse you. Take my advice, brother. This is our moment. We should not let it pass.”

The Duke nodded thoughtfully. “I am sure you are right,” he said.

THE KING AND QUEEN received the Duke.

François de Guise, the man of action, did not waste time. He came straight to the point.

“Your Majesties, I have a request to make, and I trust you will give me your gracious attention.”

“It is yours, cousin,” the King assured him.

“It is many years since my niece came to France,” said the Duke, “and it is touching to see the love she and the Dauphin bear toward each other. I know that both these children long for marriage, and my opinion is that it should take place as soon as possible. I am hoping that Your Majesties are of the same opinion.”

The King said: “I think of them as children. It seems only yesterday that I went to the nurseries and found the little Stuart there with François. What a beautiful child! I said then that I had never seen one more perfect, and it holds today.”

“It is a matter of deep gratification to our House,” said the Duke, “that one of our daughters should so please Your Majesty. I venture to say that Mary Stuart will make a charming and popular dauphine.”

Catherine glanced at her husband and murmured: “All you say is true, Monsieur de Guise. The little Stuart is charming. It seems that she only has to smile in order to turn all Frenchmen’s heads. She will indeed be a beautiful dauphine… when the time comes.”

“That time is now,” said the Duke, with that arrogance which was second nature to him.

The King resented his tone, and the Queen lowered her eyes that neither of the men should see that she was pleased by the King’s resentment.

She said quickly: “In my opinion—which I beg Your Majesty and you, Monsieur de Guise, to correct, if it seems wrong to you—these are but two children… two delightful children whom everyone loves and wishes the greatest happiness in the world. I know that to plunge two young children into marriage can be alarming for them. It might even injure that pretty comradeship which delights us all.” She was looking at the King appealingly; she knew she had turned his thoughts back to their own marriage all those years ago when he was a boy, of much the same age as François was now, with a girl beside him, a quiet, plain Italian girl—Catherine herself—whom he had never been able to love.

The King’s lips came tightly together; then he said: “I agree with the Queen. As yet they are too young. Let them wait a year or so.”

In exasperation the Duke began: “Sire, I am of the opinion that these two are ripe for marriage—”

The King interrupted coldly: “Monsieur de Guise, your opinion can be of little moment if, in this matter of our children’s marriage, it differs from that of the Queen and myself.”

The Duke was dismissed. He was furious. He had no alternative but to bow and retire, leaving this matter of the marriage as unsettled now as it had been before he had spoken.

BUT THE Cardinal and the Duke were not the men to let important matters slide. The Cardinal was quite sure that at all costs the delay must be ended.

He walked with the King in the gardens. He was more subtle than his brother. He talked first of the Protestant party in Scotland, of those lords who were in league with John Knox and were turning his little niece’s realm from the Catholic faith. The King, as an ardent Catholic, could well see the danger that lay in that.

“Your Majesty knows that my niece’s bastard brother, Lord James Stuart, is one of these men, and with him are the most powerful men in Scotland—Glencairn, Morton, Lorn, Erskine, Argyle. It is open war against the true faith in Scotland. A sad state of affairs, Your Majesty.”

The King agreed that it was so.

“We shall have them repudiating Mary Stuart next and setting the bastard over them. That, no doubt, is his plan.”

“They’ll never allow a bastard to rule them.”

“Who knows what that fanatic Knox will lead them to! They might well say, better a baseborn Protestant than a true Catholic queen.”

Henri said: “It shall never happen. We’ll send armies to subdue them.”

“Sire, since Saint Quentin we are not as strong as we were. If you will forgive the boldness, may I suggest that these barbarians could be made to respect my niece more if her status were raised. If she were not merely the Queen of Scotland but also the Dauphine of France they would think twice about flouting her in favor of the bastard.”