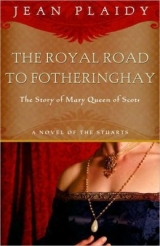

Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

FOUR

THE JUNE NIGHT WAS HOT AND THE QUEEN LAY TOSSING on her bed. She had suffered much during the last months, but now her greatest ordeal was upon her.

Her women were waiting now, and she knew that they did not expect her to leave her bed alive.

She was weary. Since the death of David she had become increasingly aware of the villainies of those about her; she could put no great trust in anyone. Even now, in the agony of a woman in childbirth who has suffered a painful pregnancy, she could not dismiss from her mind the thought of those hard, relentless men. Ruthven was dead; he had died in exile; but his son would be a troublemaker like his father. Morton, Lindsay, George Douglas, Boyd, Argyle were all traitors. Moray, her own brother, she knew, had been privy to the plot, and the plot had been not only to murder David Rizzio, but to destroy her. Maitland of Lethington—her finest statesman, a man whose services she needed, a man who had always shown a gentle courtesy which she had not often received from others—was of doubtful loyalty. He had fled to the Highlands with Atholl—surely a proof that he was not without guilt.

These men were dangerous, but there was one, the thought of whom depressed her so much that she felt she would welcome death. Why had she married Darnley whom she was beginning to hate more than she had believed it was possible to hate anyone?

He was loyal to nobody. He betrayed all those with whom he had worked against David. Now he was in a state of torment lest she pardon those lords who were in exile and they return to take their revenge on one who had turned informer. He sulked and raged in turn; he whimpered and blustered; he cringed and demanded his rights. She could not bear him near her.

It was an unhealthy state of affairs. It was true that with the followers mustered by Huntley and Bothwell she had returned triumphant to Edinburgh, and the lords responsible for Rizzio’s murder—with the exception of Moray who, she must feign to believe, was innocent of complicity—had all hastened to hide themselves. Some minor conspirators had been hanged, drawn and quartered—a proceeding which she deplored for its injustice, but which she was powerless to prevent. Bothwell was in command and, although he was the bravest man in Scotland, as a statesman he could not measure up to Maitland or Moray.

So she made her will and thought of death without any great regret.

She had failed; she saw that now. If only she could go back one year; if only she could go back to the July day when she had walked into the chapel at Holyroodhouse and joined her future fortunes with those of Darnley! How differently she would act and how different her life might consequently be!

She would have come to understand that she could have rallied her people to her and deprived her brother of his power. She had to be strong, but there was this terrible burden to hinder her; she had married the most despicable man in Scotland and he had all but ruined her.

But now the pains were on her and it was as though a curtain was drawn, shutting out those grim faces which tormented her; but the curtain was made of pain.

Between bouts of pain she noticed that her dear ones were about her. There was Beaton who suffered with her. Poor Beaton! Thomas Randolph had been sent back to England in disgrace, for he had been discovered to be trafficking with the rebels and exposed—not only as a spy for his mistress, which was understandable—but as one who worked against the Queen with her Scottish enemies. Poor Beaton! thought Mary. Like myself she is unlucky where she has placed her affections. There was dear Flem on the other side of her—heartbroken because Maitland had fled from the Court. Sempill was in disgrace and dearest Livy was with him.

But for the murder of David they would all be happy. And but for Darnley’s treachery David would be alive now.

I hate the father of this child! reflected Mary. Evil things are said of me. There is doubtless whispering in the corridors now. Who is the father of the Prince or Princess who is about to be born—Darnley or David? Who is it—the King or the secretary? That was what people were asking one another.

Darnley might be with them when they whispered, and it would depend on his mood of the moment whether he defended or defamed her.

Why did I marry such a man? she asked herself. Now that I am near dying I know that I can only wish to live if he should be taken from me.

Beaton was putting a cup to her lips.

“Beaton—” began Mary.

“Do not speak, dearest,” said Beaton. “It exhausts you. Save your strength for the child.”

Save your strength for the child! Do not fritter away your strength in hating the child’s father.

There came to her then that strength which never failed her in moments of peril. She battled her way through pain.

At last, from what seemed far away, she heard the cry of a child.

Mary Beaton was excitedly running from the apartment crying: “It is over. All is well. The Queen is delivered of a fair son.”

HER SON WAS BORN—that child who, she prayed, would unite her tortured land with the kingdom beyond the Border; for she knew that there could be no real peace between them until they were joined as one country under one sovereign. Her kingdom must be held for him as well as for herself.

There was one thing she must make sure of immediately. It should not be said that this little James Stuart was a bastard. Rumors of bastardy meant trouble in the life of a would-be king.

Already she had noticed the scrutiny of those who studied the baby. She saw the faint twitch of the lips, the appraising gaze. Now who does he resemble? Is it Darnley? Are his eyes particularly large? I wonder if he will be a skilled musician.

Her first task was not a pleasant one. She must feign friendship with her husband. She must not allow him to pour poison into people’s ears, for he would do that even though it was clear that by so doing he injured himself.

She called Darnley to her in the presence of all the people who crowded the chamber and said in a loud voice: “My lord, you have come to see our child. Look into his bonny face. God has blessed you and me with a son, and this son is begotten by none but you.”

Darnley bent over the child. She was implying that she knew what slander had been spread. He was afraid of her and all that she could do to punish him. He was afraid of those lords who were implicated in the Rizzio plot. They were now in exile, but once let them return, and he feared that his position would be as perilous as David’s had been. He was uncertain how to act. At times he felt he must cringe before his wife; at others he wished to show that he cared nothing for her; but when she confronted him with a serious matter such as this, he was always at a loss.

Mary looked from her husband, who had bent over the child, to those lords who stood by watching. She said in a loud ringing voice: “I swear before God, as I shall answer to Him on the day of judgment, that this is your son and that of no other man. I wish all gentlemen and ladies here to mark my words. I say—and God bear me witness—that this child is so much your son that I fear the worse for him.”

She turned to the nobleman nearest her bed.

“I hope,” she said, “that this child will unite two kingdoms, my own and that of England, for I hold that only in such union can peace be established between the two countries.”

“Let us hope,” said Moray, “that the child will inherit these two kingdoms after yourself. You could not wish him to succeed before his mother and father.”

“His father has broken with me,” said Mary sadly.

Darnley stuttered: “You cannot say that! You swore that all should be forgiven and forgotten, that it should be between us as it was in the beginning.”

“I may have forgiven,” said Mary, “but how can I forget? Your accomplices would have done me to death, remember… and not only me… but this child you now see before you.”

“But that is all over now.”

“It is all over and I am tired. I wish to be left alone with my son.”

She turned wearily from him, and silently the lords and ladies filed out of the bedchamber.

While Mary slept the whispering continued through the castle.

She had sworn that Darnley was the father. Would she have sworn that if it were not true? Would she have called God to witness if David had been the father?

Surely not, for her condition was not a healthy one; and the chances that she would die were great.

But whatever was said in the Castle of Edinburgh, and whatever was said in the streets of the capital, there would always be those to ask themselves—Who is the father of the Prince—Darnley or David?

SHE HAD two objects in life now—to care for her baby and to escape from her husband. He was constantly beside her—pleading, threatening. He was no longer indifferent. He fervently wished to be her husband in fact. She must not lock him from her bedchamber, he cried. She must not set guards at the door for fear he tried to creep on her unaware.

He would cry before her, thumping his fists on his knees like a spoiled child. “Why should I be denied your bed? Am I not your husband? What did you promise me when you persuaded me to fly with you? You said we should be together. And it was all lies… lies to make me the enemy of Morton and Ruthven. You took their friendship from me and you gave me nothing in return.”

“I give nothing for nothing,” she said contemptuously. “They never had any friendship for you.”

“You are cruel… cruel. Who is your lover now? A woman like you must have a lover. Do not imagine I shall not discover who he is.”

“You know nothing of me,” she told him. “But learn this one thing and learn it for all time. I despise you. You nauseate me. I would rather have a toad in my bed than you.”

“It was not always so. Nor would it be so. How have I changed? There was a time when you could scarcely wait for me. Do not think I do not remember how eager you were… more eager than I.”

“That is done with. I do not excuse my own folly. I merely tell you that I now see you as you really are, and I shudder to have you near me.”

These quarrels were the talk of the Court. Darnley himself made no secret of them. When he was drunk he would grow maudlin over his memories. He would confide in his companions details of the Queen’s passion which had now turned to loathing. Sometimes he wanted to kill somebody… anybody. He wanted to kill Bothwell who was now high in the Queen’s favor, and had been since the death of David. Some said that Bothwell would take David’s place; and it did seem that the Earl was more arrogant than ever. Some said Moray would be the one to take David’s place. The Queen did not trust him, but his standing in the country was firm.

Darnley was afraid of Bothwell. The Earl had a habit of inviting his enemies to single combat, so Darnley shifted his gaze from Bothwell to Moray. Moray was a statesman rather than a fighter. Darnley felt that in single combat he would be better matched with Moray than with Bothwell.

He began to brood on the influence Moray had with the Queen; he remembered that Moray had been against the marriage in the first place.

He burst in on Mary one evening in August and cried out that he was tired of being left out of affairs, and he would no longer stand by and allow insults to be heaped upon him.

Mary took little notice of such outbursts. She was playing chess with Beaton, and went on with the game.

Darnley kicked a stool across the apartment.

“Your move, Beaton,” said Mary.

“Listen to me!” roared Darnley.

Mary said: “I’ve got you, I think, Beaton, my dear. Two moves back you had a chance.”

“Stop it!” cried Darnley. “Stop ignoring me. Come here. Come here at once. I tell you, I’m tired of being treated thus. You will come with me now… and we will resume our normal relations.”

“Will you leave this apartment,” said the Queen, rising from the chess table, “or shall I have you forcibly removed?”

“Listen to me. If it were not for my enemies I should have my rights. I should be King of this realm. I should be master in our apartments. I would not allow you to turn me out.”

“Oh dear,” sighed Mary, “this is very tiresome. We have heard all this before, and we are weary of the repetition.”

There was one thing which infuriated him beyond endurance, and that was not to be treated seriously. He drew his sword and cried: “Erelong you will see that I am not ineffectual. When I bring you your brother’s bleeding head, you will know what I mean. He is against me. He always has been. I am going to kill Moray. I shall waste no more time.” With that he rushed from the room.

Mary sat down and buried her face in her hands. “I can’t help it,” she sobbed. “He fills me with such shame. I wish to God I had never seen him. I would to God someone would rid me of him. Beaton … I doubt that he will attempt anything, but go at once to my brother and tell him in my name what he has said. He had better be warned for if aught should happen to James it would doubtless be said that I had had a hand in it.”

Mary Beaton hurried to do her bidding while Mary sat back and stared helplessly at the chessboard. She might pretend indifference to him, but how could she be indifferent? All that he did humiliated her beyond expression.

Oh God, she thought, how I hate him!

MORAY KNEW well how to deal with Darnley and his folly.

Calmly he summoned Darnley to appear before him and a company of the most important of the lords at the Court. Darnley, afraid to refuse to appear, went reluctantly and was put through an examination by Moray himself who forced him to confess that he had uttered threats against him. Darnley blustered and denied this, until witnesses were brought who had overheard his words to the Queen.

Always at a loss in a crisis, Darnley lied and blustered and was easily proved to be both lying and blustering. He looked at the cold faces of his accusers and knew that they were his enemies. He broke down and sobbed out that everyone was against him.

Had he spoken threats against Moray? they insisted.

Yes … yes … he had, and they all hated him; they were all jealous of him because the Queen had chosen to marry him; and although she appeared to hate him now, once it had been a very different story.

“I must ask you,” said Moray, “to withdraw those threats and to swear before these gentlemen that you will not attempt to murder either me or any of those whom you believe to be your enemies. If you will not do this, it will be necessary to place you under arrest immediately.”

He was beaten and he knew it. They were too clever for him. He had to submit. He had to ask Moray’s pardon; he had to swear not to be foolish again.

They despised him; they had made that clear. They did not think it worthwhile to arrest him; they did not want to punish him; they merely wished to make him look a fool.

MARY WAS ABLE to forget her unhappiness for a time. Something rather pleasant had happened. Her dear Beaton, after being miserable on the banishment of Randolph, had fallen in love.

Mary was happy about this. It seemed a charming solution to something which had worried her. She wished she could have overlooked Randolph’s perfidy for the sake of poor Beaton. But that could not be, and the man had had to go; but now Beaton was in love again and this time it was with Alexander Ogilvie of Boyne.

This was a particularly happy state of affairs, for Mary had given her consent to the marriage of Bothwell with Jean Gordon, and Jean Gordon had once been promised to this very Alexander Ogilvie. He must have recovered from the loss of Jean, for now he seemed eager to marry Mary Beaton.

She told Bothwell of this. “I am so happy about it. Mary Beaton is such a charming girl, and I am glad to see her so happy. I shall have the marriage contract drawn up at once.”

“I see, Madam,” said Bothwell. “Was this Ogilvie not the man to whom my wife was once promised?”

“Did you not remember then? It is the very same. Ah, my lord, I expect you have made dear Jean forget she ever had a fancy for this man.”

She wondered how Jean enjoyed being married to the man. She had heard rumors that he had not mended his ways since marriage. But, she thought comfortably, Jean would know how to deal with trouble of that sort.

She gave herself up to the pleasure of preparing for Beaton’s marriage. There was one who was a little saddened by the prospect of another marriage. Poor Flem! Maitland was still in exile. Flem talked of him often, pointing out to the Queen that he was her best statesman, demanding to know if it was not folly to keep in exile a great man whose one desire was to work for his Queen.

“Dear Flem,” said Mary, “I can understand your feelings. Maitland is charming and clever. I know that. But if he were not involved in the murder of poor David, why did he find it necessary to go away?”

“Madam, he knew that Bothwell was his enemy and he also knew that you trusted Bothwell more than any man.”

“Happily would I have trusted Maitland if he would have allowed me to.”

“Dearest, you could trust him. He is your loyal subject and you need him. You know that none has his subtle cleverness. You know he is the greatest statesman in this country.”

“I believe you are right in that, Flem.”

“Then, dear Madam, forgive him—if there is anything to forgive. Recall him. You know that he was no friend to Morton and Ruthven. Oh, it is true that he did not care for David. Remember he was your first minister, before David took his place in your trust. And why did David take his place? Only because Lord Maitland was doing you good service in England, to which country you sent him knowing that he could serve you at the English Court more wisely than any of your subjects.”

“You are a good advocate, Flem, and I will think about it. I believe it is very likely that I shall recall the fellow.”

“Dearest…”

“Oh, I do not think that he is without blame. But you must keep him in order if I allow him to return, and you must warn him that he must be as faithful to me as his wife is, and that it is due to my love for her that I pass over his disaffection.”

Flem kissed her mistress’s hand and went on kissing it.

BOTHWELL HEARD rumors that Maitland was about to be recalled. He cursed aloud. He did not like Maitland. The suave courtier was too cunning for him. He feared that if Maitland returned to Court it would not be long—with the influence of Mary Fleming—before some charge would be raked up against Bothwell which might result in his falling from the Queens favor. He did not forget Maitland’s share in bringing about his exile from the Court. He also suspected Maitland had played some part—though perhaps a small one—in the plot to poison him. They were natural enemies, and he must do all he could to prevent his return to Court.

He wondered how he should proceed. What he needed was a secret audience with the Queen. He decided that if he could only be alone with her, he could talk more freely and make his arguments more plausible without interruption. The Queen was but a lass, in his opinion—rather emotional and sentimental. He believed that if he could explain how Maitland had always been his enemy, how the fellow had not always been a faithful supporter of the Queen, how he, Bothwell, had never once failed her when danger threatened, there might yet be time to dissuade her from bringing Maitland back to Court.

He knew that in a few days the Queen would be going to the Exchequer House—a small dwelling in Edinburgh which was next to one occupied by a man who had been a servant of his. To this small house Mary was going to check some of her accounts and make arrangements for the clothes which would be needed for her son’s christening. She wanted to be alone for a few days—apart from an attendant woman and one servant—so that she could not only go into this matter of accounts but come to a decision as to who should be given the guardianship of the young Prince.

Everything seemed to be working in Bothwell’s favor. He believed that at the Exchequer House it would not be a difficult matter to obtain a private interview with Mary.

He would not ask for it in case it should be denied to him. Mary would guess what he wished to say and, characteristically, would not wish him to say it. Doutbless Mary Fleming had swayed her one way, and she would be afraid that he would attempt to sway her another. Mary would wish to please them both and, since she could not in this instance give him his wish, she would do all in her power to avoid seeing him.

He understood her very well—a sentimental lassie who was no match for the wily wolves who prowled about her. Therefore she should have a private interview with him, not knowing that it would take place until it was forced upon her. For his purpose she could not have chosen to go to a better place than the Exchequer House—indeed this idea would not have come to him had she not been going there.

David Chambers, who had been one of his superior servants, was the man who lived next door to the Exchequer House; and the gardens of these two houses were separated by a high wall, but in this high wall was a door which made it easy to pass from one to the other. David Chambers had done good service to his master, and Bothwell had rewarded him well. Many a woman had entertained Bothwell at the house of Chambers; and if Bothwell desired to meet a certain woman he merely told Chambers this, and Chambers arranged a meeting. Chambers’s house had proved for some time a useful place of assignation.

Moreover the two servants who were with the Queen at the Exchequer House were the Frenchman, Bastian, and Lady Reres. Bastian need not be considered; he would be lodged in the lower part of the house. As for Lady Reres, by great good fortune, she had been Margaret Beaton, sister to Janet, and on his visits to Janet there had been times when—perhaps he had called unexpectedly—only Margaret had been there to entertain him. Margaret, who was very like her sister, had proved an excellent substitute, a sensible creature, ready for the fun of the moment and not one to bear a grudge. Women, such as the Beaton sisters, were the best friends a man could have. Passionate women, such as Anna Throndsen, could cause a great deal of trouble. He was thankful now that Anna had gone back to Denmark, leaving their son behind to be cared for by his mother’s servants. But he need not think of Anna now. All he need concern himself with was the fact that Margaret Beaton, now Lady Reres, was to be the lady-in-waiting to the Queen in the small house, and that he had easy access to that house through his servant David Chambers.

It was all very easy to arrange. He went through the door in the wall and asked Bastian to bring Lady Reres to him and to keep his coming a secret. Lady Reres soon appeared. She was heartily glad—and very amused—to see him.

She wanted to know what devilment he planned.

“Merely to see the Queen. A matter of some importance. What I want is a secret interview and do not think I can get it when she is living in state. So I chose this time when she is living here in seclusion for a few days. Margaret, could you take me to her?”

“I will ask if she will see you.”

“That will not do. She will say no. She will send for her ministers or her courtiers or someone. This is a secret matter, and I wish none to hear it but herself.”

“My lord, you ask too much.”

“Not from you, Margaret.” He pushed her playfully against the wall. “Remember the good times we had?”

“Well, they are over,” said plump Lady Reres with a laugh.

“Never to be forgotten by either of us.”

“Why should you choose to remember me out of the six thousand… or have I been niggardly in the counting?”

“I have not kept the score, but you are one I remember well.”

Lady Reres laughed again. “I would, of course, help you all I could. But how can I let you into her apartment? I tell you she is alone here, apart from myself and Bastian. What will she say to me when she knows I have allowed you to come in?”

“She need not know. You need not let me in. But leave her alone after supper this evening and leave the door open. I will slip up by the back stairs. You will be discussing next day’s supper with Bastian in the lower part of the house and thus not hear me.”

“We are responsible for the safety of the Queen.”

“Do you think I would hurt the Queen? I tell you it is a matter of great importance … a state matter. It is imperative that I see her … for her sake as well as mine. Now, will you keep my secret? Say nothing to her, leave her after supper, and see that the way is clear for me.”

“I don’t like it.”

“But you will do it for an old friend?”

“I know nothing of it, remember.”

“Why, bless you, Meggie, you know nothing of it. The fault will all be due to my boldness.”

He gave her a loud kiss of gratitude, and she went away thinking of him nostalgically as he used to be in the old days when he came to see Janet. He had changed, she supposed. He was more interested in state matters. His marriage had mayhap sobered him. Ah! They had been good times. She felt young again thinking of them.

THE QUEEN had supped in her small bedchamber and the remains of the meal were still on the table. She was very tired and glad to be alone, free from ceremony for a few days.

She was wearing a velvet robe—loose-fitting—and her chestnut hair hung loose for the weather was warm. It was a comfort to be able to dress thus.

Suddenly she heard a step on the stair. It must be Margaret returning. She was thinking: We shall be leaving here perhaps the day after tomorrow, but there is still another day in which to live quietly.

The door opened and she started up in amazement, for Lord Bothwell was standing on the threshold.

“Lord Bothwell!” she cried.

“Yes, Madam.” He bowed.

“How did you get in here? Why did you not give notice of your coming?”

“I will explain,” he said.

She was angry because now in this small room in this small house his arrogance seemed more in evidence than ever.

“I wish to hear no explanations,” she said. “I will call Bastian to show you out.”

He did not move. He stood by the door as though barring her way.

“Lord Bothwell,” she said, “what is the meaning of this?”

He did not speak. He was looking at her flushed face, her disordered hair. He was looking at her as he had never looked before. In that moment she was afraid of him. She would have pushed past him, but he caught her. His grip hurt her and she cried out, trying to twist her arm free.

She stammered: “This… this unwarranted… insolence…. How… how dare you! You shall suffer for this.”

He had gripped her by the shoulders and bent her backward.

“Shall I?” he said. His eyes were glazed; they looked dazzling in his sunburned weather-beaten face. “Then there shall be something worth suffering for.”

“You come here,” she panted. “You come in… unannounced…. Release me at once. You shall pay dearly for this.”

Bothwell was the Borderer now; the statesman had fled. He had forgotten that he had come to talk about Maitland. He had been in situations of a similar nature before. He had felt this wild excitement, this demand for satisfaction at all costs. But this was different; this was piquant; this was more exciting than those other occasions. Many women had partnered Bothwell in such scenes, but never a queen before this.

He cared for nothing now but the surrender of the woman. If it meant death, it must go on now. It was the first time he had seen her, stripped of her royalty. It was the first time he had discovered what a very desirable woman she was.

He pulled her toward him and roughly caressed her body. Mary was trembling with rage and sobbing with terror. She knew that this encounter had cast its warning over her many a time. It was the meaning of those insolent looks. He would treat her now as he would any peasant over the Border. He cared nothing for the fact that she was the Queen. There was only one thing that was of importance to him; the satisfaction of his vile nature.

She kicked and tried to bite. It was all she could do for she was pinioned. He had turned and, holding her firmly with one arm, locked the door.

She stammered: “This… this… outrage…. It is the most monstrous thing that ever happened to me.”

“It will also be the most enjoyable,” he said.

“You will lose your head for this.”

“No,” he said. “You have never had a lover yet, my Queen. Wait… have patience…. Don’t fight… and then the sooner will you come to pleasure.”

He had torn her robe from her shoulder. She was conscious of her weakness compared with his great strength. He lifted her in his arms then as though he read her thoughts and would stress the fact that she was impotent to resist him.

“It is no use screaming,” he said. “No one will hear. They’ll not break the door down if they do. How could they? Poor Bastian! That feeble Frenchman? Fat Margaret? Have no fear. None shall disturb us.”

“You have gone mad,” she said.

“It is a temporary madness, they say.”

“You forget… I am the Queen.”

“Let us both forget it. Queens should not bring their royalty to the bedchamber.”

“Put me down. I command you. I beg you.”

“I mean to… here on your bed.”

He put her onto it. She tried to scramble up but he had forced her down. She struggled until she was exhausted. The room was spinning round her. She thought afterward that she fainted for a while. She was not sure. She was aware of his heart and hers beating together… heavy, ominous beating.

She had no strength left to hold him off. She lay passive without resistance, without resentment or anger. There was nothing but this extraordinary, overwhelming emotion—this mingling of fury and pleasure, of a terrible shame and an unaccountable joy.

SHE LAY ON her bed long after he had gone.

What has happened to me? she asked herself. Why do I not send for Moray? Why do I not order the immediate arrest of Lord Bothwell? On what charge? The rape of the Queen?

She remembered that she would present a strange sight if Lady Reres came to the room. She got up from her bed. She gazed at her torn clothes which he had thrown onto the floor. How explain them? But they would be part of the evidence she would need to bring him to the scaffold. The rape of the Queen! She could hear the words now. She could hear John Knox thundering them from his pulpit. He would say that she had encouraged Bothwell. “No,” she said aloud as if in answer to his imagined accusation. “It is not true. I always disliked him. Now I hate him. How dared he? The shame of it… the shame of it!”