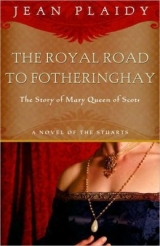

Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Author’s Note

It is probable that no historical character has ever aroused more ardent supporters or more fierce detractors than has Mary Stuart. Strangely enough these admirers and detractors extol or defame irrespective of their religious faith. This is most unusual and is no doubt due to the fact that, in contrast with the disputes which almost always involved those who lived in the sixteenth century, those which concern Mary are not, in the main, about religion. The questions so fiercely debated in Mary Stuarts case are: Did she write the Casket Letters? Was she a willing partner in her abduction and rape? Was she a murderess?

My research for Royal Road to Fotheringhay led me to discover a Mary who was sometimes quick-tempered, sometimes gentle, always charming, tolerant and warm-hearted; but because I have been unable to exonerate her from implication in the murder of Darnley I want to stress that when assessing Mary we must not weigh her deeds and behavior by present-day standards. She lived in an age when life was cheap and cruelty part of daily existence. Many men and women of the past who were considered during their day as patterns of virtue would receive a very different verdict if they had lived today. For example: Michelet says that Gaspard de Coligny was the most ennobling character of his times; yet the discipline he imposed on the battlefield would be called cruelty today, and it is by no means certain that he was guiltless of the murder of François de Guise. It is very necessary to remember this when considering the part Mary played in luring her husband to the house in Kirk-o’-Field. In her generation she was kinder and more tolerant than most of the people around her; but she herself faced death more than once, and in the sixteenth century, the elimination of human obstacles was not deemed a crime of such magnitude as it is today.

Other questions asked are: How could a woman, having lived as virtuously as she had (even Brantôme had no scandalous gossip to record of Mary) suddenly indulge in an adulterous passion, and take part in the murder of the husband who stood between her and her lover? How could she, beautiful and cultured, suddenly become the slave of Bothwell, the uncouth ruffian from the Border?

I have sought explanations by posing questions of my own. Mary was not healthy and her pictures do not support all we hear of those outstanding attractions; so what was the secret of that immense physical charm which she undoubtedly possessed? I believe it was largely due to an extremely passionate nature which was but half awakened when she met Darnley and not fully so until it was recognized by that man—so experienced in amatory adventures—the virile Bothwell. I believe that dormant sensuality to have been the secret of her appeal. And why was it so long in coming to fruition? I think I have found the answer in Mary’s relationship with the Cardinal of Lorraine, that past master in all things sensual, whose closeness to Mary would have given him every chance to understand her; and, being the knowledgeable man he was, he could not fail to do this. The scandal—the origin of which was traced to Bothwell—that Mary was the Cardinal’s mistress, cannot have been justified; yet theirs was no ordinary relationship, and I am of the opinion that it was the reason why the passions of such a passionate woman were so long dormant.

The Casket Letters and the poems are perhaps the most discussed documents in British history. If they were actually written by Mary, there can be no doubt of her guilt. But are they forgeries? It is impossible to answer yes or no, for the mystery of the Casket Letters has never been solved. It seems clear that some of the poems could have been written by no other hand than Mary’s, and it is equally clear that some parts of the letters could never have been her composition. (I refer in particular to the crude reference to Darnley in Letter No. 2, the most incriminating of all the Casket documents.) Yet might it not be that the letters were in some part forgeries, in others Mary’s actual writings? Because a part is false it does not follow that the whole is. Who else could have written those revealing poems? Who among the Scots was sufficiently skilled in the French language? Maitland of Lethington? He was a cunning statesman, but was he a poet?

Mary was raped by Bothwell. Those who would proclaim her an angel of virtue are ready to concede that. An important question is: When did the rape occur? Was it in the Exchequer House or later at Dunbar after the abduction? Was Mary herself in the plot to abduct her? If so, she and Both-well must have been in love before the staging of that extraordinary affair, and it is more than likely that the rape took place at the Exchequer House. Buchanan’s ribald account is clearly exaggerated. The story of Lady Reres being lowered into the garden in order to bring Bothwell from his wife’s bed to that of the Queen might have been written by Boccaccio and is too crude to be believed; but Mary was at the Exchequer House, and Bothwell’s servant did live next door. Why should not Buchanan’s story be founded on truth?

I have discarded, selected and fitted my material together with the utmost care and I hope I have made a plausible and convincing picture of Mary, the people who surrounded her, and the circumstances which made Fotheringhay the inevitable end of her royal road.

I have studied many works and am indebted in particular to the following:

History of France. M. Guizot.

History of England. William Hickman Smith Aubrey.

British History. John Wade.

Henri II. H. Noel Williams.

Feudal Castles of France. Anon.

Lives of the Queens of Scotland and English Princesses

(Vols. III, IV, V, VI, VII). Agnes Strickland.

Letters of Mary Queen of Scots (Vols. I and II),

with Historical Introduction and Notes by Agnes Strickland.

The Scottish Queen. Herbert Gorman.

The Love Affairs of Mary Queen of Scots. Martin Hume.

The Queen of Scots. Stefan Zweig.

John Knox and the Reformation. Andrew Lang.

The Life of John Knox. George R. Preedy.

Lord Bothwell. Robert Gore-Brown.

J.P.

Mary the Queen

ONE

THROUGH THE GREAT ROOMS OF THE CASTLE OF STIRLING five little girls were playing hide-and-seek. They were all in their fifth year and all named Mary.

She, whose turn it was to seek, stood against the tapestry, her eyes tightly shut, listening to the echo of running feet, counting softly under her breath: “Ten… eleven… twelve …”

It was fair now to open her eyes, for they would all be out of sight. She would count up to twenty and then begin to search. Livy would give herself away by her giggling laughter. She always did. Flem would betray herself because she wished to please and thought it wrong that her beloved Mary should not succeed immediately in everything she undertook. Beaton, the practical one, and Seton, the quiet one, would not be so easy.

“Fifteen… sixteen …”

She looked up at the silken hangings. They were soft and beautiful because they came from France. Her mother spoke often of France—that fairest of lands. Whenever her mother spoke of France a tenderness came into her voice. In France there was no mist, it seemed, and no rain; French flowers were more beautiful than Scottish flowers; and all the men were handsome.

In France Mary had a grandfather, a grandmother and six uncles. There were some aunts too but they were not so important. The uncles were all handsome giants who could do anything they wished. “One day,” her mother often said, “you may see them. I want them not to be ashamed of you.”

“Eighteen… nineteen… twenty …” She was forgetting the game.

She gave a whoop of warning and began the search.

How silent the rooms were! They had chosen this part of the castle for hide-and-seek because no one came here at this hour of the day.

“I am coming!” she called. “I am coming!”

She stood still, listening to the sound of her voice. Which way had they turned—to the left or to the right?

She wandered through the rooms, her eyes alert. Was that a shadow behind the stool? Was that a bulge behind the hangings?

She had now come into one of the bedrooms and stood still, looking about her. She was sure she had heard a movement. Someone was in this room. Yes, there was no doubt.

“Who are you?” she called. “Where are you? Come out. You are found.”

There was no answer. She ran about the room, lifting the curtains, looking behind the furniture. Someone was somewhere in this room, she felt sure.

She lifted the curtains about the bed and there was little Mary Beaton.

“Come out, Beaton,” commanded the little Queen.

But Beaton did not move. She just lay stretched out on her stomach, resting on her elbows, propped up on her hands.

Mary cried impatiently: “Come out, I said.”

Still Beaton did not move.

The color flamed into Mary’s face. She remembered that she was Queen of Scotland and the Isles. Great men knelt before her and kissed her hand. Her guardians, those great Earls—Moray, Huntley and Argyle—never spoke to her without first kneeling and kissing her hand. And now fat little Beaton refused to do as she was bid.

“Beaton, you heard me! You’re found. Come out at once. The Queen commands you.”

Then Mary understood, for Beaton could no longer contain her emotions; she stretched full out on the floor and began to sob heartbrokenly.

All Mary’s anger disappeared. She immediately got onto her knees and crawled under the bed.

“Beaton… dear Beaton… why are you crying?”

Beaton shook her head and turned away; but Mary had her arms about her little friend.

“Dear Mary,” said the Queen.

“Dear Mary,” sobbed Beaton.

Rarely did the Queen call one of her four friends by their Christian names. It only happened in particularly tender moments and when they were alone with her, for Mary the Queen had said: “How shall we know which one we mean, since we are all Marys?”

They did not speak for some time; they just lay under the bed, their arms about each other. The little Queen could be haughty; she could be proud; she could be very hot-tempered; but as soon as those she loved were in trouble she wished to share that trouble and she would do all in her power to comfort them. They loved her, not because she was their Queen whom their parents and guardians had commanded them to love and serve, but because she made their troubles her own. It was not long before she was sobbing as brokenheartedly as Beaton, although she had no idea what Beaton’s trouble was.

At last Mary Beaton whispered: “It is… my dear uncle. I shall never see him again.”

“Why not?” asked Mary.

“Because men came and thrust knives into him … so he died.”

“How do you know? Who told you this?”

“No one told me. I listened.”

“They say it is wicked to listen.”

Beaton nodded sadly. But the Queen did not blame her for listening. How could she? She herself often listened.

“So he is gone,” said Mary Beaton, “and I shall never see him again.”

She began to cry again and they clung to one another.

It was hot under the bed, but they did not think of coming out. Here they were close, shut in with their grief. Mary wept for Beaton, not for Beaton’s uncle, the Cardinal—a stern man, who had often told the Queen how good she ought to be, how much depended on her, and what an important thing it was to be Queen of Scotland. Mary grew tired of such talk.

Now she had another picture of the Cardinal to set beside those she knew—a picture of a man lying on the floor with knives sticking into him. But she could not think of him thus for long. She could only remember the stern Cardinal who wished her to think continually of her duty to the Church.

They were still under the bed when the others found them. They crawled out then, their faces stained with tears. Mary Fleming began to cry at once in sympathy.

“Men have stuck knives in Beaton’s uncle,” announced Mary.

All the little girls looked solemn.

“I knew it,” said Flem.

“Then why didn’t you tell?” asked the Queen.

“Your Majesty did not ask,” answered Flem.

Seton said quietly: “Everyone won’t cry. The King of England will be pleased. I heard my father say so.”

“I hate the King of England,” said Mary.

Seton took the Queen’s hand and gave her one of her solemn, frightened looks. “You must not hate him,” she said.

“Mary can hate anyone!” said Flem.

“You should not hate your own father,” said Seton.

“He is not my father. My father is dead; he died while I was in my cradle and that is why I am the Queen.”

“If you have a husband,” persisted Seton, “his father is yours. My nurse told me so. She told me that you are to marry the English Prince Edward, and then the King of England will be your father.”

The Queen’s eyes flashed. “I will not!” she cried. “The English killed my father. I’ll not marry the English Prince.” But she knew that it was easy to be bold and say before her Marys what she would and would not do; she was a queen and had already been forced to do so many things against her will. She changed an unpleasant subject, for she hated to dwell on the unpleasant. “Come,” she said, “we will read and tell stories to make poor Beaton forget.”

They went to a window seat. Mary sat down and the others ranged themselves about her.

But the vast room seemed full of frightening shadows. It was not easy to chase away unpleasant thoughts. They could read and tell stories but they could not entirely forget that Mary Beaton’s uncle had been stabbed to death and that one day the Queen would have to leave her childhood behind her and become the wife of some great prince who would be chosen for her.

THE QUEEN-MOTHER noticed at once the traces of tears on her daughter’s face. She frowned. Mary was too emotional. The fault must be corrected.

The little Queen’s stern guardians would have noticed the marks of tears.

Since the Cardinal had been murdered there were only three guardians—Moray, Huntley and Argyle.

The Queen-Mother herself could have shed tears if she had been the woman to give way to them. The Cardinal was the one man in this turbulent land whom she had felt she could trust.

She looked about the assembly. There was the Regent, Arran, the head of the house of Hamilton, and of royal blood, longing to wear the crown of Scotland; Arran, who could not be trusted, whom she suspected of being the secret friend of the English, who had hoped to marry his son to the English King’s daughter Elizabeth, and who doubtless had hopes of his son’s wearing not only the crown of Scotland but that of England. There was false Douglas, so long exiled in England and only daring to return to Scotland after the death of James; Douglas, who had schemed with the King of England. He it was who had agreed, when in the hands of the English, to the marriage between the little Queen and Prince Edward. It was he who had come with soft words to the Queen-Mother, setting forth the advantages of the match.

There was the giant Earl of Bothwell who had hopes of marrying the Queen-Mother. Was he loyal? How could she know who in this assembly of men was her friend? Scotland was a divided country, a wild country of clans. There was not in Scotland that loyalty to the crown which the English and French Kings commanded.

And I, she thought, am a woman—a Frenchwoman—and my child, not yet five, is the Queen of this alien land.

All eyes were on the little girl. What grace! What beauty! It was apparent even at so young an age. Even those hoary old chieftains were moved by the sight of her. How gracefully she stood! How nobly she held her head! She had all the Stuart beauty and that slight touch of something foreign which came from her French ancestors and which could enhance even the Stuart charm.

“God protect her in all she does,” prayed her mother.

She raised her eyes and caught the flashing ones of Lord James Stuart—Stuart eyes, heavy lidded, not unlike Mary’s, beautiful eyes; and the proud tilt of the head denoted ambition. He was a boy yet in his early teens. But ambition smoldered there. Was he thinking even now: Had my father married my mother, I should be sitting in the chair of state and it would be my hand those men would kiss?

“God preserve my daughter from these Scots!” prayed the Queen-Mother.

Now the little Queen stood while the great chieftains came forward to kiss her hand. She smiled at them—at Arran, at Douglas. They looked so kind. Now came Jamie—dear Jamie. Jamie knelt before her but when he lifted his eyes to her face he gave her a secret wink, and she felt the laughter bubble up within her. It was rather funny that tall, handsome Jamie should kneel before his little sister. She knew why of course, for she had demanded to know. It was because although his mother was not the Queen, the King, her father, had also been Jamie’s father. Mary had other brothers and sisters. It was a pity, she had said to her Marys, that their mothers had not been queens, for it would have been fun to have a large family living about her—even though she was so much younger.

Now her mother would not allow her to stay.

“The Queen is very tired,” she said, “and it is time she was abed.”

Mary wanted to stay. She wanted to talk to Jamie, to ask questions about the dead Cardinal.

But although they all kissed her hand and swore to serve her with their lives, they would not let her stay up when she wanted to. She knew she must show no annoyance. A queen did not show her feelings. Her mother had impressed that upon her.

They all stood at attention while she walked out of the apartment to where her governess, Lady Fleming, was waiting for her.

“Our little Queen does not look very pleased with her courtiers,” said Janet Fleming with one of her gay bursts of laughter.

“No, she is not,” retorted Mary. “I wanted to stay and talk to Jamie. He winked when he kissed my hand.”

“Gentlemen winking at you already—and you the Queen!” cried Janet. Mary laughed. She was very fond of her governess who was also her aunt. For one thing red-haired Janet was very beautiful, and, although no longer in her first youth, was as full of fun as her young charge. She was a Stuart, being the natural daughter of Mary’s grandfather; and little Mary Fleming was her daughter. She could be wheedled into letting the Queen have much of her own way, and Mary loved her dearly.

“He is only my brother,” she said.

“And should be thankful for that,” said Janet. “Were he not, it would be an insult to the crown.”

She went on chattering while Mary was prepared for bed; it was all about dancing, clothes, sport and games, and when her mother came to the apartment Mary had temporarily forgotten the grief which Beaton had aroused in her.

The Queen-Mother dismissed all those who were in attendance on the Queen, so Mary knew that she was going to be reprimanded. It was a strange thing to be a queen. In public no one must scold; but it happened often enough in private.

“You have been crying,” accused Marie of Lorraine. “The traces of tears were on your face when you received the lords.”

Fresh tears welled up in Mary’s eyes at the memory. Poor Beaton! She remembered those desperate choking sobs.

“Did your women not wash your face before you came to the audience?”

“Yes, Maman, but it was such a big grief that it would not come off.”

The Queen-Mother softened suddenly and bent to kiss the little face. Mary laughed and her arms went up immediately about her mother’s neck.

The Queen-Mother was somewhat disturbed. Mary was too demonstrative, always too ready to show her feelings. It was a charming trait, but not right, she feared, in a girl of such an exalted position.

“Now,” admonished Marie, “that is enough. Tell me the reason for these tears.”

“Men have stuck knives into Beaton’s uncle.”

So she knew! thought her mother. How could you keep terrible news from children? Mary had good reason to shed tears. Cardinal Beaton, upholder of the Church of Rome in a land full of heretics, had indeed been her friend. Who would protect her now from those ambitious men?

“You loved the Cardinal then, my daughter?”

“No.” Mary was truthful and spoke without thinking of the effect of her words. “I did not much like him. I cried for poor Beaton.”

Her mother smoothed the chestnut hair, so soft yet so thick, which rippled back from the white forehead. Mary would always weep for the wrong reasons.

“I share little Beaton’s grief,” said the Queen-Mother, “for the Cardinal was not only a good man, he was a good friend.”

“Why did they kill him, Maman?”

“Because of Wishart’s death … so they say.”

“Wishart, Maman? Who is he?”

What am I saying? the Queen-Mother asked herself. I forget she is only a baby. I must keep her from these tales of bloodshed and murder as long as I can.

But Mary was all eager curiosity now. She would find out in some way. Behind those deeply set, beautiful eyes there was an alert mind, thirsting for knowledge.

“Wishart was a heretic, my child, and he paid the penalty of heretics.”

“What penalty was that, Maman?”

“The death which is accorded heretics fell to him.”

”Maman… the flames!”

“How do you know these things?”

How did she know? She was not sure. Had one of her Marys whispered it? Had she seen pictures in the religious books? She covered her face with her hands and the tears began to flow from her eyes.

“Mary! Mary, what has come over you? This is no way to behave.”

“I cannot bear it. He was a Scotsman, and they have burned him… they have burned him right up.”

Marie de Guise was alarmed. A little knowledge was so dangerous, and her daughter was so impulsive. What would she say next? She was precocious. How soon before some of these men began to corrupt her faith? They would do everything in their power to turn her into a heretic. It must not be. For the honor of the Guises, for the glory of the Faith itself, it must not be.

“Listen to me, child. This man Wishart met his just reward, but because the Cardinal was a man of the true faith, Wishart’s friends murdered him.”

“Then they did right! I would murder those who burned my friends.”

“A little while ago you were crying for the Cardinal.”

“No, no,” she interrupted. “For dear Beaton.”

The Queen-Mother hesitated by the bedside. How could she explain all that was in her mind to a child of this one’s age? How could she expect this baby mind to understand? Yet she must protect her from the influence of heretics. How did she know what James Stuart whispered to the child when he pretended to frolic with her? How did she know what Arran and Douglas plotted?

“Listen to me, Mary,” she said. “There is one true Church in this world. It is the Church of Rome. At its head is the Pope, and it is the duty of all monarchs to serve the true religion.”

“And do they?”

“No, they do not. You must be careful what you say. If you do not understand, you must come to me. You must talk to no one about Wishart and the Cardinal… to no one… not even your Marys. You must remember that you are the Queen. You are but little yet, but to be a queen is not to be an ordinary little girl who thinks of nothing but playing. We do not know who are our friends. The King of England wants you in England.”

“Oh, Maman, should I take my Marys with me?”

“Hush! You are not going to England.” The mother took her child in her arms and held her tightly. “We do not want you to go to England. We want to keep you here with us.”

Mary’s eyes were wide. “Could they make me go?”

“Not unless …”

“Unless?”

“It were by force.”

Mary clasped her hands together. “Oh, Maman, could they do that?”

“They could if they were stronger than we were.”

Mary’s eyes shone. She could not help it. She loved excitement and, to tell the truth, she was a little tired of the castle where all the rooms were so familiar to her. She was never allowed to go beyond the castle grounds; and when she played, there were always men-at-arms watching.

Her mother came to a sudden decision. The child must be made to understand. She must be shocked, if need be, into understanding.

“You are being foolish, child,” she said. “Try to understand this. The worst thing that could happen to you would be for you to be taken to England.”

“Why?”

“Because if you went your life would be in danger.”

Mary caught her breath. She drew back in amazement.

It was the only way, thought the Queen-Mother. There was too much danger and the child must be made aware of it.

“The King of England has said that he wishes you to go to England to be brought up with his son.”

“You do not wish me to marry Edward?”

“I do not know … as yet.”

The Queen-Mother stood up and walked to the window. She looked across the country toward the south and thought of the aging monarch of England. He had demanded the marriage for his son, and that Mary be brought up in the Court of England as a future Queen of England. A good enough prospect… if one were dealing with any but the King of England. But there was a sinister clause in the agreement. If the little Queen of Scots died before reaching an age of maturity, the crown of Scotland was to pass to England. The royal murderer should never have a chance of disposing of Mary Stuart. How easy it would be! The little girl could fall victim to some pox… some wasting disease. No! He had murdered his second and fifth wives and, some said, was preparing to murder his sixth. He should not add the little Queen of Scots to his list of victims.

But how tell such things to a child of five years!

Marie de Guise turned back to the bed. “Suffice it that I shall not allow you to go to England. Now … to sleep.”

But Mary did not sleep. She lay sleepless in the elaborate bed—the bed with the beautiful hangings sent to her by her glorious uncles—and thought of that ogre, the King of England, who might come at any moment to carry her off by force.

NOW THE LITTLE QUEEN was aware of tension. She knew that the reason why she must never go beyond the castle walls without a strong guard was because it was feared she would be abducted.

She called the Marys together. Life was exciting. They must learn about it. Here they were shut up in Stirling Castle playing hide-and-seek, battledore and shuttlecock, reading, miming, playing games; while beyond the castle walls grown-up people played other games which were far more exciting.

One day when they were all at play, Flem, who happened to be near the window, called to them all. A messenger was riding into the courtyard, muddy and stained with the marks of a long ride, his jaded horse distressed and flecked with foam.

The children watched—five little faces pressed against the window. But the messenger stayed within the castle and they grew tired of waiting for him to come out, so they devised a new game of messengers. They took it in turn to be the messenger riding on a hobby horse, come from afar with exciting news concerning the King of England.

Later they were aware of glum faces about them; some of the serving men and women were in tears and the words Pinkie Cleugh were whispered throughout the castle.

Lady Fleming shut herself in her apartment and the five Marys heard her sobbing bitterly. Little Flem beat on the door in panic and called shrilly to be allowed to come in. Then Janet Fleming came out and looked blankly at the five little girls. Her own Mary ran to her, and Janet embraced her crying over and over again: “My child… my little Mary… I still have you.” Then she went back into her room and shut the door, taking Flem with her.

Mary, left alone with her three companions, felt the tears splashing on to her velvet gown. She did not understand what had happened. She was wretched because her dear Aunt Janet and little Flem were in some trouble.

“What is Pinkie?” she demanded; but even Beaton did not know.

It was impossible to play after that. They sat in the window seat huddled together, waiting for they knew not what.

They heard a voice below the window, which said: “They say Hertford’s men are not more than six miles from the castle.”

Mary knew then that danger was close. Hertford, her tutors had told her, was the Lord Protector of England who ruled until Edward—that boy who might very well be her husband one day—was old enough to do so himself, for King Henry had died that very year. To Mary, Hertford was the monster now; he was the dragon breathing fire who would descend on the castle like the raiders on the Border and carry the Queen of Scotland off to England as his prize.

That was a strange day—a queer, brooding tension filled the castle. Everyone was waiting for something to happen. She did not see her mother that evening and her governess was not present when she went to her apartment for the night.

At last she slept and was awakened suddenly by dark figures about her bed. She started up, thinking: He has come. Hertford has come to take me to England.

But it was not Hertford. It was her mother, and with her were the Earl of Arran, Lord Erskine and Livy’s father, Lord Livingstone, so that she knew this was a very important occasion.

“Wake up,” said her mother.

“Is it time to get up?”

“It is an hour past midnight, but you are to get up. You are going away on a journey.”

“What! At night!”

“Do not talk so much. Do as you are told.”

This must be very important, for otherwise even her mother would not have talked to her thus in the presence of these noble lords. She had to be a little girl now; she had to obey without question. This was no time for ceremony.

Lady Fleming—her eyes still red with weeping—came forward with her fur-trimmed cloak.

“Quickly,” said Lady Fleming. “There is no time to be lost. If your lordships will retire I will get my lady dressed.”

While Mary was hustled into her clothes she asked questions. “Where are we going? Why are we going now? It’s the night… the dead of night…”

“There is no time for questions.”

It should have been an exciting adventure, but she was too tired to be conscious of most of that journey. She was vaguely aware of the smells of the night—a mingling of damp earth and misty air. Through the haze of sleep she heard the continued thudding of horses’ hoofs. Voices penetrated her dreams. “Pinkie… Pinkie…. Hertford close on our heels. Cattle driven over the Border. Rape… murder… fire… blood.”