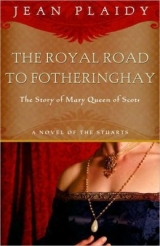

Текст книги "Royal Road to Fotheringhay "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

TWO

IN THE SMALL ROOM ADORNED WITH THE FINEST OF HER French tapestries, Mary was playing chess with Beaton. Flem was at her embroidery and Livy and Seton sat reading quietly.

Mary’s thoughts were not really on the game. She was troubled, as she was so often since she had come to Scotland. There were times when she could shut herself away in Little France, but she could not long succeed in shutting out her responsibilities. These Scots subjects of hers—rough and lusty—did not seem to wish to live in peace with one another. There were continual feuds and she found herself spending much time in trying to reconcile one with another.

Beaton said that Thomas Randolph, the English ambassador, told her that affairs were managed very differently in the English Court, and that the Tudor Queens frown was enough to strike terror into her most powerful lords. Mary was too kindly, too tolerant.

“But what can I do?” Mary had demanded. “I am powerless. Would to God I were treated like Elizabeth of England!” She was sure, she said, that Thomas Randolph exaggerated his mistress’s power.

“He spoke with great sincerity,” Beaton had ventured.

But Beaton was inclined to blush when the Englishman’s name was mentioned. Beaton was ready to believe all that man said.

Mary began to worry about Beaton and the Englishman. Did the man—who was a spy as all ambassadors were—seek out Beaton, flatter her, perhaps make love to her, in order to discover the Queens secrets?

Dearest Beaton! She must be mad to think of Beaton as a spy! But Beaton could unwittingly betray, and it might well be that Randolph was clever enough to make her do so.

In France, the Cardinal of Lorraine had been ever beside Mary, keeping from her that which he did not wish her to know. Now she was becoming aware of so much of which she would prefer to remain in ignorance. Her brother James and Maitland stood together, but they hated Bothwell. The Earl of Atholl and the Earl of Errol, though Catholics, hated the Catholic leader Huntley, the Cock o’ the North. There was Morton whose reputation for immorality almost equaled that of Bothwell; and there was Erskine who seemed to care for little but the pleasures of the table. There was the quarrel between the Hamilton Arran and Bothwell which flared up now and then and had resulted in her banishing Bothwell from the Court, on Lord James’s advice, within a few weeks of her arrival, in spite of all his good service during the voyage.

She was disturbed and uncertain; she was sure she would never understand these warlike nobles whose shadows so darkened her throne.

She recalled now that warm September day when she had made her progress through the capital. She had been happy then, riding on the white palfrey which had with difficulty been procured for her, listening to the shouts of the people and their enthusiastic comments on her beauty. She had thought all would be well and that her subjects would come to love her.

But riding on one side of her had been the Protestant Lord James, and on the other the Catholic Cock o’ the North; and the first allegorical tableau she had witnessed on that progress through the streets had ended with a child, dressed as an angel, handing her, with the keys of the city, the Protestant Bible and Psalter—and she had known even then that this was a warning. She, who was known to be a Catholic, was being firmly told that only a Protestant sovereign could hold the key to Scotland.

Moreover it had been a great shock, on arriving at Market Cross, to find a carved wooden effigy of a priest in the robes of the Mass fixed on a stake. She had blanched at the sight, seeing at once that preparations had been made to burn the figure before her eyes. She had been glad then of the prompt action of the Cock o’ the North—an old man, but a fierce one—who had ridden ahead of her and ordered the figure to be immediately removed. To her relief this had been done. But it had spoiled her day. It had given her a glimpse of the difficulties which lay ahead of her.

She had returned from the entry weary, not stimulated as she used to be when she and François rode through the villages and towns of France. But she had determined to make a bid for peace and, to show her desire for tolerance, had appointed several of the Reformers to her government. Huntley, the Catholic leader, was among them with Argyle, Atholl and Morton as well as Châtelherault. Her brother, Lord James Stuart, and Lord Maitland were the leaders; and in view of the service he had rendered her, she could not exclude Bothwell, though that wild young man had succeeded in getting himself dismissed from Court—temporarily, of course. She had no wish to be severe with anyone.

Beaton looked up from the board and cried: “Checkmate, I think, Your Majesty. I think Your Majesty’s thoughts were elsewhere, or I should never have had so easy a victory.”

“Put away the pieces,” said the Queen. “I wish to talk. Now that we have our rooms pleasantly furnished, let us have a grand ball. Let us show these people that we wish to make life at Court brighter than it has hitherto been. Perhaps, if we can interest them in the pleasant things of life, they will cease to quarrel so much about rights and wrongs and each others opinions.”

“Let us have a masque!” cried Flem, her eyes sparkling. She was seeing herself dressed in some delightful costume, mumming before the Court, which would include the fascinating Maitland—surely, thought Flem, the most attractive man on earth—no longer young, but no less exciting for that.

Livy was thinking of tall Lord Sempill who had made a point of being at her side lately, surely more than was necessary for general courtesy, while Beaton’s thoughts were with the Englishman who had such wonderful stories to tell of his mistress, the Queen of England. Only Seton was uneasy, wondering whether she could tell the Queen that one of the priests had been set upon in the streets and had returned wounded by the stones which had been thrown at him; and that she had heard there was a new game to be played in the streets of Edinburgh, instigated by John Knox and called “priest-baiting”.

The Queen said: “Now, Seton! You are not attending. What sort of masque shall it be?”

“Let there be singing,” said Seton. “Oh, but I forgot… Your Majesty’s choir is short of a bass.”

“There is a fine bass in the suite of the Sieur de Moretta,” said Livy.

“And who is he?” asked Mary. “But he will be of little use, for Moretta will soon be returning to his master of Savoy, I doubt not; and he will take your singer with him.”

“Then Your Majesty is not contemplating the marriage which Moretta came to further?” asked Beaton diffidently.

Mary looked at her sharply. Could it be that she was gathering information for Randolph? No! One look at dear Beaton’s open face reassured her.

She took Beaton’s hand and pressed it warmly. It was a mute plea for forgiveness because she had secretly doubted her. “No, I shall not marry the Duke of Ferrara, though it was for that purpose Savoy sent Moretta among us—for all that this is reputed to be a courtesy visit. But we stray from the point. What of this singer? Even temporarily he might be of some service to us.”

“He has the voice of an angel!” declared Flem.

“If he is as good as you say, we might ask him to stay with us after his master goes back.”

“Does Your Majesty think he would?”

“It would entirely depend on what position he holds under his master. If it is a humble one, he may be glad of the opportunity to serve me; and I doubt his master would refuse to spare him.”

“Madam,” said Seton, “I heard him sing yesterday, and I have never heard the like.”

“We will have him brought here to my apartments. He shall sing for us. What is his name?”

“That I do not know,” said Flem.

Mary turned to the others, but none knew his name.

Seton suddenly remembered. “I fancy I have heard him called Signor David by his fellows.”

“Then we will send for Signor David. Flem dear, send a page.”

The Queen had her lute brought to her, and the five ladies were discussing the music they would sing and play, when Signor David appeared.

He was a Piedmontese, short of stature and by no means handsome, but his graceful manners were pleasing; he bowed with charm, displaying a lively awareness of the honor done to him, while accepting it without awkwardness.

“Signor David,” said the Queen, “we have heard that you possess a good voice. Is that true?”

“If Your Majesty would wish to judge of it, your humble servant will feel himself greatly honored.”

“I will hear it. But first tell me—what is your position in the suite of my lord de Moretta?”

“A humble secretary, Your Majesty.”

“Now, Signor David, sing for us here and now.”

She played the lute and rarely had she looked more charming than she did at that moment, sitting there in her chair without ceremony, her delicate fingers plucking at the strings, her eyes shining, not only with her love of music, but because she was about to do this poor secretary a kindness.

And as he sang to her playing, his glorious voice filled the apartment and brought tears to their eyes; it was a voice of charm and feeling as well as power, and they could not hear it and remain unmoved.

When the song ended, the Queen said with emotion: “Signor David, that was perfect.”

“I am delighted that my poor voice has given Your Majesty pleasure.”

“I would have you join my choir.”

“I have no words to express my delight.”

“But,” went on the Queen, “when you leave with your master, we shall find my choir will be so much the poorer that I may wish you had never joined it!”

He looked distressed.

“Unless,” said Mary impulsively, “you wished to remain in my service when your master goes.”

His answer was to fall on his knees. He took her hand and lifted it to his lips. “Service… service,” he stammered, “to the most beautiful lady in the world!”

She laughed. “Do not forget you will be choosing this land of harsh winters in exchange for your sunny Italy.”

“Madame,” he replied, “if I may serve you, that would be sun enough for me.”

How different were the manners of these foreigners, she mused, from those of blunt Scotsmen! She liked the little man with the large and glowing eyes.

“Then if your master is willing, when he leaves Scotland you may exchange his service for mine. What is your name—your full name? We know you only as Signor David.”

“It is David Rizzio, Madame. Your Majesty’s most humble and devoted servant henceforth.”

IT WAS Christmas time and the wind howled up the Canongate; it buffeted the walls of Holyrood, and the Queen had great logs burning in the fireplaces throughout the palace. To her great regret, most of the French retinue which had accompanied her to Scotland had now returned to France, and of her immediate circle only Elboeuf remained.

There was trouble in the streets, and at the root of that trouble were the lusty Bothwell and the deranged Arran.

Bothwell did not forget that it was due to Arran that he had been dismissed from the Court. Such a slight to a Border warrior could not be allowed to pass. Arran, and the whole Hamilton clan, never missed an opportunity of maligning Bothwell and had spread far and wide the scandal concerning him and Anna Throndsen—the poor Danish girl, they called her—whom he had seduced, made a mother and lured from her home merely to become one of those women with whom he chose to amuse himself as the fancy took him.

Arran—a declared Puritan and ardent follower of Knox—was not, Both-well had discovered, in a position to throw stones. Accordingly Bothwell devised a plot for exposing the Hamilton heir in the sort of scandal with which he had conspired to smear Bothwell.

Bothwell had two congenial companions. One of these was the Marquis d’Elboeuf, always ready for a carousal to enliven the Scottish atmosphere, and Lord John Stuart, Mary’s baseborn brother, who admired the Hepburn more than any man he knew and was ready to follow him in any rashness. Bothwell cultivated Mary’s brother for two reasons—one because the young man could do him so much good at Court, and the other because he hoped he would marry his sister, Janet Hepburn, a redheaded girl as lusty—or almost—as her brother, and who had been involved in more than one scandal and had already been lavishly generous with her favors to Lord John.

The followers of Bothwell and Lord John swaggered about the streets of Edinburgh, picking quarrels with the followers of the Hamiltons. But that was not enough for Bothwell’s purpose.

“What a merry thing it would be,” he cried, “if we could catch Airan flagrante delicto. Then we should hear what his friend John Knox had to say to that!”

Elboeuf was overcome with mirth at the prospect. Lord John wanted to know how they could do it without delay.

“’Tis simple,” explained Bothwell. “Often of a night he visits a certain woman. What if we broke into the house where they stay, catch him in the act, and drive him naked into the night? Imagine the Puritan heir of the Hamiltons, running through the streets without his clothes on a cold night because he has been forced to leave them in the bedchamber of his mistress!”

“Who is his mistress?” asked Lord John.

“There we are fortunate,” explained Bothwell. “She is the daughter-in-law of old Cuthbert Ramsay who was my grandmother’s fourth husband, and lives in his house.”

“Old Cuthbert is no friend to you.”

“No, but in the guise of mummers we should find easy entry into his house.”

“’Tis a capital plan!” cried Elboeuf. “And what of the poor deserted lady? I could weep for her—her lover snatched from her! Will she not be desolate?”

“We’ll not leave her desolate!” laughed Bothwell. “She will find us three adequate compensation for the loss of that poor half-wit. It would seem our game with Arran would be but half finished if we did not console the lady after dismissing the lover.”

So it was agreed.

The night was bitterly cold as the three conspirators swaggered down to St. Mary’s Wynd, wherein stood the house of Cuthbert Ramsay. They were dressed as Christmas revelers and masks covered the faces of all three, who were well known as the most profligate men in Scotland.

They found the door of the house locked against them; Bothwell was infuriated because, knowing the customs of Ramsay’s house, he realized that there must have been warning of their coming.

“Open the door!” he shouted. He could see the dim lights through some of the windows, but no sound came from behind the door. Bothwell’s great shoulders had soon crashed it open and, with the help of his two friends, he forced an entry into the house.

Seeing a shivering girl trying to hide herself, Bothwell seized her and demanded to be shown the apartments of Mistress Alison Craig with all speed. The girl, too terrified to do aught else, ran up the staircase with the three men in pursuit. She pointed to a door and fled.

Bothwell banged on the door. “Open!” he cried.

“Who is there?” came the instant request. Bothwell turned to his friend and grinned, for the voice was that of Alison Craig.

“It is one who loves you,” said Bothwell, “come to tell you of his love.”

“My lord Bothwell…”

“You remember me? I thought you would.”

“What… what do you want of me?”

Still grinning at his companions, Bothwell answered: “That which I always want of you.”

It was easier to force an entry into Alison’s room than it had been into the house. Soon all three of them were in the room, where Alison, half clothed, cowered against the wall. The open window told its own story.

Lord John ran to the window.

“What… do you want here?” demanded Alison.

“Where is Arran?” asked Bothwell.

“I… do not understand you. I do not understand why you come here… force your way into my room …”

“He has made good his escape,” said Lord John turning from the window.

Elboeuf had placed his arm about Alison. She screamed and struck out at him.

“How dare you… you… you French devil!” she cried.

Lord John said: “Madam, you would prefer me, would you not? See, I am young and handsome, and a Scot… a bold brave Scotsman whom you will find very different from the dastard who has just left you. Do not trust Frenchmen, for as the good people of Edinburgh will tell you, the French have tails.”

“Go away… you brutes… you loathsome …”

Elboeuf interrupted: “Dear Madam, can you tolerate these savage Scots? He who has deserted you at the first sign of trouble is a disgrace to his nation. I will show you what you may expect from one who comes from a race that is well skilled in the arts of love.”

Alison tried to shut out the sight of those three brutal faces. She had had lovers, but this was a different affair. In vain she tried to appeal to some streak of honor in those three. Perhaps in Lord John, she thought. He was so young. Perhaps the Frenchman whose superficial manners were graceful. Never… never, she feared, in Bothwell.

He had pushed the others aside. He said: “Arran is my enemy and it is meet and fitting that I should be the first.”

Feeling his hands upon her, Alison gave out a piercing scream. She slipped from his grip and ran to the window.

“Help!” she cried. “Good people…. Help! Save me from brutes and ruffians …”

Bothwell picked her up effortlessly. He had played a similar role in many a scene in his Border raids. He threw the terrified woman onto the bed.

“Harken!” cried Lord John.

Elboeuf’s hand went to his sword.

The servants had not been idle. They had lost no time in making it known that Bothwell and his friends had broken into the house of Arran’s mistress. The Hamilton men were rushing up the stairs.

It was a very different matter, attacking a defenseless woman, from facing many armed men, and all three realized that they would be in danger of losing their lives if they hesitated. Already it was necessary to fight their way through those men who were on the staircase. Bothwell led the way, his sword flashing. As for Lord John and Elboeuf—no one cared to wound the Queen’s uncle or her brother—and in a short time the three men were clear of the house.

They separated and ran to safety before the streets were filled with the gathering Hamilton clan.

The matter did not end there. The Hamiltons continued to throng the streets, swearing they would do to death their enemy Bothwell. The followers of Elboeuf and Lord John were gathering about them; and it seemed as though a great battle might shortly take place in the streets of Edinburgh.

The Queen, hearing of this, was terrified and uncertain how to deal with the trouble. Once more she was thankful for her resourceful brother, for James acted promptly, and with the Cock o’ the North and himself riding at its head led an armed force to disperse the quarreling clans.

“Every man shall clear the streets on pain of death!” was Lord James’s proclamation.

It had the desired effect.

But Bothwell felt the little adventure had not entirely failed. All Edinburgh now knew that, for all his piety, Arran had a mistress, and that was just what he had wished to proclaim.

THE LORD JAMES and Maitland were closeted together discussing the affair of Bothwell and Arran.

“Arran,” said Maitland, “being little more than half-witted, may be the more easily dismissed. It is the other who gives me anxious thoughts.”

Lord James stroked his sparse beard and nodded. “You’re right. Bothwell is a troublemaker. I would like to see him back in his place on the Border. It may well be a matter for rejoicing that our Queen has been brought up in the French Court. I fancy she finds us all a little lacking in grace. What she must think of that ruffian Bothwell I can well imagine.”

“Yet he received part of his education in France, remember.”

“It touched him not. He is all Borderer. I think the Queen would be pleased to have him removed from Court.”

“None could be more pleased at that than I. If we can marry the Queen into Spain …”

There was no need to say more. Both men understood. Marry the Queen into Spain … or somewhere abroad. Leave Scotland for Lord James and Maitland. It was a twin ambition.

“Bothwell would try to prevent such a marriage,” said Maitland. “He would wish to see the Queen married to a Scot.”

“We will advise the Queen to banish him from Court.”

“What of the others who were equally guilty?”

“Her brother! Her uncle! Let us satisfy ourselves with ridding the Court of Bothwell. He is our man.”

They sought audience with the Queen. She was angry about this brutal outrage which had taken place in the midst of the Christmas celebrations. She was preparing for her brother Robert’s marriage to Jane Kennedy, the daughter of the Earl of Cassillis; she had grown fond of Jane and was delighted to do special honor to her. And after that marriage there was to be another: Lord Johns to Janet Hepburn. There could be so much gaiety and pleasure, yet these barbarians could not be content to enjoy it—nor would they let others enjoy it in peace.

“Madam,” said Lord James, “this is a monstrous affair. Such outrageous conduct is a disgrace to our country.”

“Yet it would seem that I am powerless to prevent it.”

“No, no, Your Majesty,” said Maitland. “The miscreants can be punished—and should be, as a warning to others.”

“How can I punish my uncle Elboeuf?”

“You can only warn him. It will be said that, as a Frenchman from an immoral land, his sins are not to be taken as seriously as those of honorable Scotsmen. Soon he will be leaving our country. A warning will suffice for Elboeuf. As for our brother, he is but a boy—not yet twenty—and I think led astray by more practiced ruffians. He can be forgiven on account of his youth. But there is one, the ringleader, who is not so young and should not be forgiven. Bothwell is the instigator of all the trouble, Madam, and as such should be severely dealt with.”

“I have no doubt that you are right,” said Mary. “But it seems to me wrong to punish one and let the others go free.”

“While Bothwell remains at Court there will be trouble,” said Lord James.

Mary replied: “I had thought to give them a severe warning, to threaten them with stern punishment if they offend again, and then forget the matter. It is Christmastide …”

“Madam,” said Maitland “these matters cannot be put right by being thrust aside. The Hamiltons were gravely insulted, and for the sake of peace, Bothwell should at least be exiled.”

“Summon him to your presence, dearest sister,” said James. “Tell him he must leave the Court. I assure you, it is safer so.”

Mary was resigned. “I suppose you are right,” she said. “Have him brought here.”

HE CAME INTO her presence, arrogant as ever; and she was conscious of his veiled insolence.

“My lord Bothwell, you have been guilty of an outrage. You have broken into the house of peaceful citizens and caused much distress. I know that you were not alone. You had two companions. One is a guest in this kingdom—my own guest; the other is a young and impressionable boy. Therefore I hold you responsible for this disturbance.”

“Would you not cast a little blame on the Hamiltons, Madam?”

“From what I hear the trouble started when you forced an entry into a house in St. Mary’s Wynd.”

“The trouble started long before that, Madam. If you wish for an account of the scores I have to settle with Arran, I shall be pleased to give it.”

Mary waved her hand impatiently. “Please … I beg of you… tell me no more. I am tired of your perpetual bickering. You are dismissed the Court. Go back to the Border. Go anywhere, and if you are not soon gone I shall be forced to make your punishment more drastic.”

“Madam,” began Bothwell, “I appeal to your sense of justice. If you feel I have done aught to deserve blame, then must you cast some blame on Arran. Let me meet him in single combat and settle our affairs thus.”

“No, my lord,” she said sternly, “there shall be no more bloodshed if I can prevent it.”

She looked up into his face helplessly. Her glance clearly said: What can I do? How can I punish Arran with his father, Châtelherault, and the whole Hamilton clan behind him—to say nothing of his supporter John Knox? Go away. If you must fight, fight the English on the Border. I want Scotland left in peace.

“Leave the Court,” she said. “Go at once.” She smiled suddenly. “You will have many preparations to make for your sisters wedding.”

His smile answered hers.

He would retire from Court; he would proceed with his preparations for his sisters wedding; and when the Queen’s brother became his brother-in-law, he would be better fitted to pit himself against Lord James and the whole Hamilton clan.

“My sister,” he said, “will be a sad woman if Your Majesty does not honor us at Crichton with your presence.”

The Queen was still smiling. So he was going. He was not going to plunge into one of those Knox-like arguments which distressed her. “Of a certainty I shall wish to be present at my brother’s wedding,” she told him.

LESS THAN TWO weeks later Mary set out for Crichton Castle, the chief seat of the Hepburn family.

John Knox thundered against the marriage of these wicked people who disgusted virtuous Scotsmen with their fornications and lecherous lives. This baseborn brother of the whore of Babylon, he declared, was known to be a whoremonger; and what of the woman he was marrying? “A sufficient woman for such a man!”

Knox was left in Edinburgh reviving old scandals.

“Janet Hepburn, the bride-to-be!” he cried. “To how many has she been handfast, I should like to know—or rather I should shudder to know—before she prepares herself to enter into this most unholy matrimony with the sanction of the Queen?”

Mary was glad to put many miles between herself and the ranting preacher. She was glad to enter the old castle whose unscalable walls had been built to resist the ruffian raiders from across the Border. Sternly it faced the Cheviots and the Tyne—the Hepburns’ challenge to marauding Englishmen.

Here she dwelt as the guest of Lord Bothwell. She liked the wild outspoken girl who was as bold as her brother, and was not surprised that John wished to marry her.

Lord James, who accompanied her, was more dour than ever. He did not approve of this alliance with the Hepburns. The girl was wild, he complained to Mary. John was too young to be saddled with such a wife. There were nobles of higher standing who would have been delighted with the honor of marrying a Stuart.

She refused to listen to his gloomy prophecies. Here was an occasion for merriment—a wedding, and the wedding of her own brother at that. Lord Bothwell was making a great entertainment for her and she was determined to enjoy it.

“James,” she coaxed, “now that Robert and John are married, you must be the next.”

James listened soberly. He had been thinking for a long time of marriage with the Lady Agnes Keith, who was the daughter of the Earl Marischal. Marry he would, but his marriage would in no way resemble this one between Janet Hepburn and his brother John. For all he knew, John had been caught by the woman at one of the handfast ceremonies where young men and women met round a bonfire and went off to copulate in the woods. Lord James had no desire for such questionable pleasures. When he married Lady Agnes it would be because he had made up his mind that such a match would be advantageous. As yet he was hesitant.

Mary was laughing at him. “Yes, James,” she said, “I shall insist. Your marriage shall be the next. You cannot allow your young brothers to leave you behind.”

Lord James pressed her hand in a brotherly, affectionate way. It was impossible not to be fond of her. She was so charming and so ready to take his advice.

Mary gave herself up to the pleasure of being entertained. And what an entertainment Lord Bothwell had prepared for her! She knew that he had sent raiders beyond the Border to procure that which made their feast, but what of that! He was a Borderer with many a score to settle. The eighteen hundred does and roes, the rabbits, geese, fowls, plovers and partridges in hundreds, may have come from the land of the old enemy, but it mattered not at all. They made good feasting. And after the feast there were sports on the green haugh below the castle as had rarely been seen in Scotland, and the leaping and dancing of the bridegroom won the acclamation of all.

MARY NOW felt better and happier than she had for many weeks. Could it be true—as her Marys suggested—that her native land was more beneficial to her health than France had been? It was absurd. These draughty castles, so comfortless compared with the luxury of the French châteaux, and food which although plentiful was less invitingly prepared… could it be possible that these discomforts could make her better? Perhaps it was the rigorous climate, though often when the mist hung about the rooms she felt twinges in her limbs. No. She was growing out of her ailments—that must be it. Of course her Marys declared it was due to Scotland because they were fast becoming reconciled to Scotland: Flem through Maitland; Livy through John Sempill; Beaton through the Englishman, Randolph; and Seton… well, Seton was just happy to see the others happy.

When would Mary’s time come; and who would be her husband? It seemed to Mary that every day the name of some suitor was presented to her.

The Queen of England was anxious to have a say in plans for Marys marriage. If the bridegroom did not please her, she had hinted, she would certainly not name Mary and her heirs as successors to the English throne. That spy Randolph—why was poor Beaton so taken with the man?—always seemed to be at her elbow. She pictured him in his apartment, scribbling hard, determined that his mistress should miss little of what went on in Marys Court.

And now there was to be another marriage. Lord James was at last going to marry Lady Agnes.

Mary wanted to show her gratitude to her brother, and what better time could there be than the occasion of his marriage? She longed to give him what he craved—the Earldom of Moray; but how could she grant him that Earldom when old Huntley, the Cock o’ the North—and not without reason—laid claim to it? Instead she would make him Earl of Mar and beg him to be satisfied with that.