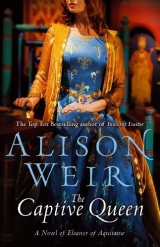

Текст книги "Captive Queen"

Автор книги: Элисон Уир

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

“I have no desire to go there,” Matilda said. “I have heard that the lords there are violent and uncontrollable.” She shot a look at Eleanor.

“It has ever been so,” Eleanor said. “That is because Aquitaine has massive rocky hills and rivers, and each lord thinks he is a king in his own valley. They have always fought among themselves, but I trust that now, thanks to their love for me and my lord’s reputation as a strong ruler, they will not be so disobedient. My cities of Poitiers and Bordeaux are always safe and quiet, and there we enjoy a good standard of living. My duchy is a land of great abbeys and churches, and the arts and letters are thriving.”

“By that, I take it you are referring to your troubadours,” her mother-in-law said, her tone dismissive. “I have heard that they sing only of love and its trivialities.”

“Love is not trivial,” Eleanor defied her. “In Aquitaine, it is an important part of life. And women are valued there as nowhere else. Believe me, madame, I know. I have lived in France—”

“Where women are required to be virtuous and live in subjection to their husbands!” the Empress cut in.

Henry, toying with his wine cup, glanced at his mother in mock surprise, wondering when she had ever lived in virtuous subjection to his father. But Matilda was a woman on a mission and did not notice.

“I dare say,” she was commenting to a frozen-faced Eleanor, “that you would not understand that, coming from Aquitaine, which, I am told, is little better than one vast brothel!”

Eleanor’s temper flared, but Henry was there before her. He had been sitting at the head of the table, listening to the exchange between his wife and his mother with amused interest, but now it had gone far enough.

“Are you suggesting that Eleanor is less than virtuous?” he barked, his blood up. “Remember she is my wife!”

His mother looked as wrathful as he did. “I’m not only suggesting it, I know it!” she retorted. “Either this woman has deceived you, my son, or you have lost all sense of respect for me in bringing her here and forcing me to receive her.”

Eleanor rose. “I am leaving,” she said hotly. “I will not be spoken of like that.”

“Will you deny, then, that you were Geoffrey’s mistress?” the Empress flung at her. Eleanor paused in her flight, drawing in her breath, and there was an awful silence before she found the words to reply. Henry’s expression was, as so often, unreadable.

“I will not deny it,” she said, her cheeks burning, “but know this, madame, that he told me he was unhappily married and that you had no more use for each other as man and woman. Do you deny that?”

“My relations with Geoffrey are no business of yours. What you did was wrong, and it was even more wrong of you to marry my son, knowing you had been his father’s leman.”

“That’s enough,” snarled Henry. “I will hear no more. And you, Mother, must keep what you know to yourself, if you wish to retain what power is left to you in the world—and my filial devotion.” His tone was sarcastic.

Matilda got to her feet. “You must both live with your consciences. It is not I who have committed the sin of incest. Mark me, there will be a reckoning one day. God is not to be mocked. And there’s no need to threaten me, Henry. I had already decided that discretion was essential—do you think I would bring shame on myself by publicly announcing that my late lamented husband had an affair with a woman who is the scandal of Christendom? Don’t think I haven’t heard the rumors—”

“Enough!” Henry bellowed, flushing with rage.

“You’re right, I’ve had enough,” spat Eleanor, and gathering up her mantle, swept regally out of the room.

“Well, I hope you’re pleased with yourself, Mother,” Henry said, his gaze thunderous.

“Your marriage made good political sense, I grant you that,” Matilda muttered. “But I can only deplore the fact that your wife has a stained reputation, and that she betrayed me with my husband, your own father. And that she has the brazen nerve to come here and expect to be honorably received.”

“Mother,” Henry said quietly, leaning forward and glaring directly into her eyes. “Perhaps you did not hear me or understand, but Eleanor is my wife, and you will treat her with respect, as I do. I love her, I love her to distraction, and you had best get used to that. It matters not to me that she has strayed from virtue in the past, for I have done the same myself, often, and so am not fit to judge her. But I know that she loves me and that she has been true to me, so let that be an end to it.”

“You are a besotted fool!” she told him. “And one day you will realize it. You are so much your father’s son, headstrong and impulsive.”

“I am your son too, Mother,” he reminded her.

“No, Henry, you come from the Devil’s stock, and more’s the pity, for the Devil takes care of his own. Now go. Leave me, I am weary.”

“Very well. Shall I crave your nightly blessing, my Lady Mother?” Henry jeered. “No, don’t bother. Since I’m descended from the Devil, it won’t do me any good. What I want from you, rather, is a truce. You don’t have to be friends with Eleanor—even I, besotted fool that you say I am, wouldn’t ask that—but I want you always to treat her with the respect due to her rank and to my wife, if that is at all possible. Is that understood?”

Matilda said nothing. Her expression was glacial.

“I’m waiting,” Henry said pleasantly.

“Very well,” was the tight-lipped reply. “Just make sure that I see her as little as possible.”

“I should imagine she wouldn’t want to see you at all,” Henry said.

“I’m really sorry, Eleanor,” Henry said, climbing into bed and taking her in his arms. “I especially regret that my mother decided to poison our reunion with her vitriol—and my first meeting with young William.” He kissed her. “He’s wonderful, isn’t he? Me to the life!”

“I love you, Henry,” Eleanor murmured, feeling vulnerable, and resting her head on his chest, taking comfort from his strength. Then she forgot all about Matilda as the familiar and much-longed-for melting sensation coursed through her body, and she gave herself up to her husband’s delightful caresses—although not for long. As needy as she, he mounted her swiftly.

“God, it’s so good to hold you again!” he cried, and then could say no more as passion overtook him. Eleanor’s desire was no less urgent, and as they lost control in unison, rolling between the sheets, grabbing and devouring each other, she thought she would die of the pleasure. Afterward, lying together in blissful euphoria, kissing gently and sensuously, they gazed at each other in wonder, shaken by the depth of their passion.

“I pray you never have to leave me for so long again,” Eleanor said, touching Henry’s cheek.

“I think I shall have to, if that’s what I’ll be coming home to!” he teased, grinning. “By the eyes of God, woman, you are a marvel! No one has ever made me feel like this.” He was being serious now.

“And shall make you feel even better …” Eleanor promised, sliding sensuously down the bed. “How like you this, my dear heart? And this?”

“Eleanor, you’re insatiable!” Henry groaned, stretching with pleasure, and chuckled. “Do you realize that for this you could end up doing penance for three years?”

Eleanor momentarily stopped what she was doing. “IfI confessed it,” she murmured, “but in truth, I consider it to be no sin.” She resumed where she had left off.

“Then we shall burn together in Hell, and be damned!” Henry gasped.

–

In the morning, the duke was up early, anxious to be out hunting. He would never lie late in bed, but was always restless to be gone.

“He makes a martyrdom of the sport,” his mother complained. She had complied with Henry’s demand, and there was an unspoken if uneasy truce between her and Eleanor when they met in the chapel before breakfast and bowed warily to each other.

“She had actually sent a message asking me if I wished to accompany her to mass,” Eleanor told Henry on his return.

“And did you?”

“Of course. She will never have cause to call me undutiful.” She set down the illuminated book she had been reading.

“Henry—”

“What’s that?” he interrupted, looking admiringly at the book with its bejeweled silver cover. He had an insatiable curiosity.

“It is The Deeds of the Counts of Anjou,”Eleanor told him. “I am learning all about your forebears.”

Henry sniffed. “It might put you off me for life! They were troublesome bastards, the lot of them.”

“It does make for very interesting reading.” she smiled. “And it explains a lot of things!”

“Hah!” cried Henry. “Don’t paint me with the same brush. Although if you listen to Abbot Bernard, I’m worse than all of them put together.”

“So he told me!” She laughed, then her face grew serious. “Henry, how long are we to sojourn in Normandy?”

“I’m not sure,” he said warily. “I wanted to talk to you.”

“You said six weeks.” The prospect of a longer stay with her dragon of a mother-in-law was more than she could stomach.

“I know, but I have just had news from Aquitaine. Some of your vassals are in rebellion. I want you to remain here while I go and teach them a lesson.”

“Rebellion?” Eleanor echoed.

“It seems they don’t like me,” Henry muttered, “but it’s nothing I can’t handle.”

“I could quell them,” she told him. “They will listen to me.”

“And that’s precisely why I am going in your stead, so that they learn to listen to me as well.”

“Henry, I insist—”

“Eleanor, my mind is made up. Don’t worry, my Lady Mother won’t eat you up while I’m gone. She’s got enough of the statesman in her to appreciate the folly of upsetting me, when her power here derives from me.”

“But Henry, you need her to govern Normandy, and she knows it,” Eleanor protested. “That’s an empty threat. She has no need to fear you.”

“Yes, but she has every need to fear you,” he retorted. “Normandy has a duchess now—why should she not rule it in my absence?”

“And when we are summoned to England? I don’t want to stay here!”

“I have many dependable Norman barons, my sweetheart. No, never fear, my mother will behave herself. And you have your ladies and young William to occupy you.”

“You make it sound as if that should be enough to content me,” Eleanor complained. “Take me with you. Let us not be parted again.”

“No,” Henry declared. “It will not be for long, and war is man’s work. Then we can look forward to another reunion.” He grinned at her suggestively.

Again Eleanor experienced that hateful feeling of being trapped and helpless.

“You just don’t understand, do you?” she fumed. “I am the Duchess of Aquitaine, and I am fit for higher things than the company of women and babies. When there is trouble in my domains, I should be with you, putting things right. We said we would do these things together, Henry! And, as you seem to have forgotten already, we have just been parted for sixteen months– sixteen months—yet you are going to leave me again. I can’t believe you would even think of that, not after last night.”

Henry came to her and caught her roughly in his arms.

“Do you think I want to leave you?” He sighed. “Ah, Eleanor, in an ideal world we would be together always, but I have vast domains to rule, and that means I must continually be on the move. Listen. I know you for an intelligent woman, and I do value your political ability, but I need to assert my authority in Aquitaine, and I need to do it alone. When those godforsaken vassals of yours have learned who’s in charge, we will rule the duchy as equals. In the meantime, all I ask is that you stay here in safety with our son.”

“Very well then,” she conceded after a pause, still simmering, “but summon me as soon as you can.”

“No, I will return to you here,” Henry said.

“But why?” she asked in dismay.

“There is news from England,” he said. “I have not yet had a chance to tell you or my mother. King Stephen is ill; it can now only be a matter of time. We must hold ourselves in readiness, and for that reason we should stay here in Normandy. It is only a short distance across the Channel from England.”

“But you are going south,” Eleanor pointed out. “What if the summons comes while you are away?”

“I shall ride like the wind and be here in ten minutes!” Henry chuckled. “And I’ll bring your rebellious vassals with me. The promise of rich pickings in England might make them like me more.”

12

12

Rouen, 1154

It was late October. In the solar of the royal palace, the two richly garbed royal ladies sat sewing by a brazier. The wind was howling outside, and the colorful tapestries on the walls stirred in the draft from the slit windows.

“Bring me more silks,” the Empress commanded, and her waiting woman scuttled away. Another appeared with goblets of cognac, which she placed on the table.

“I wish there was news of Henry,” Eleanor said, taking a sip. “Oh, that’s warming.”

“I expect the weather is as bad in the Vexin as it is here,” Matilda said. Her manner toward her daughter-in-law was still merely polite, but months of familiarity had eroded the sharp edge of the glacier. Thrown together by virtue of their rank, both women had had to make the best of it.

“I worry about Henry. He is still not over his illness.” Eleanor shuddered as she recalled her beloved’s close brush with death the month before, after he had been laid low with a rampant, burning fever. Thanks to his vigorous constitution, and no thanks to his inept doctors, he pulled through, but not before his wife and his mother had suffered some searingly anxious moments.

“I worry too, but it is imperative that he puts down this revolt,” Matilda said.

“I know that, madame, but he was still suffering fits of the shivers the night before he left.” And he had been too fatigued to make love.

“I know my son. He is strong, and a fighter. He will recover. But he hates being ill and, as you have no doubt discovered, he will never admit to any weakness, nor will he be told what to do.” The Empress smiled dourly, then turned her gimlet gaze on the younger woman. “You have heard the news about your former husband, King Louis?”

“That he has remarried—yes,” Eleanor said, rising to throw another log on the brazier. “I wish him nothing but happiness—and his bride nothing but fortitude.”

“They are saying that this Castilian princess, Constance, won him by her modesty,” Matilda murmured, “and that his subjects think he is better married than he had been.”

Eleanor ignored the barbs. She had grown too used to them. “More likely he was won by the prospect of a rich dowry from her father, King Alfonso,” she retorted. “At least he has now made peace with Henry and stopped calling himself Duke of Aquitaine. That really did irk me!”

She shifted in her chair and rested her hands on her swollen belly. She was five months gone with child, and finding the waiting tedious. She longed to be back in the saddle, riding in the fresh air, her hawk on her glove.

Mamille de Roucy burst into the room then, her rosy round face flushed with excitement. The Empress frowned at her deplorable lack of ceremony, but the damsel did not notice.

“Mesdames, there is a messenger arrived from England, much travel-stained! He says he is come from Archbishop Theobald and must see the duke urgently.”

Eleanor sat bolt upright. The Empress looked at her, and in the two pairs of eyes that met, hope was springing.

“Did you tell him that Duke Henry is not here?” Eleanor asked.

“I did, madame. He is asking to see you instead.”

“Then send him in.”

Eleanor rose, a proud and regal figure in her scarlet gown of fine wool with long hanging oversleeves. Her head was bare, her long hair plaited and bound around the slim gold filet that denoted her rank. Thus did the exhausted messenger see her when he was shown into her presence. His admiring glance paid tribute to the beauty of her face and the voluptuousness of her fecund body. He fell to his knees before her.

“Lady, allow me to be the first to salute you as Queen of England!” he cried. “King Stephen, whom God assoil, has departed this life. He died on the twenty-fifth day of October.”

“Praise be to God,” Matilda breathed exultantly, crossing herself. Eleanor did likewise, not being quite able to take in the glad tidings. She was a queen again, queen of that strange northern land beyond the sea, of which she had heard so many tales. Everything that she and Henry had schemed and hoped for had come to pass.

“I thank you for bringing me this news,” she told the messenger, giving him her hand to kiss. “The duke—nay, the King!—must be informed at once. I pray you, refresh yourself in the kitchens, then make all haste to the Vexin to my lord, and bid him return without delay, so that he may hasten to take possession of his kingdom. God speed you!”

When the man was gone, Eleanor turned to her mother-in-law, who had also risen to her feet. The Empress had a rapt expression on her handsome face.

“So God has been just at last,” she said. “These nineteen long winters of the usurper’s rule I have prayed for this and beseeched Him to uphold my rights. Now He has spoken, and my son will wear the crown that I fought over so long and bitterly.” Her eyes were shining.

“Madame, I rejoice in this happy ending to your struggle,” Eleanor said sincerely. In this moment of triumph, she could afford to be generous to her enemy. Impelled by a shared sense of jubilation, the two women embraced and kissed, each planting cool lips on the other’s cheek.

“Come,” Eleanor said, taking the initiative. “We must assemble our little court and tell them the glad news. Then we shall gather a retinue and go to the cathedral and give thanks.” And she swept out of the chamber, her woolen skirts trailing regally behind her, and for the first time daring to take precedence before the Empress.

There was much to be done while they waited for Henry. Letters to be sent, announcing his accession, provision made for the governance of Aquitaine in its rulers’ absence, and administrative matters to be dealt with, for the duchy of Normandy was to be left in Matilda’s capable hands. As a matter of courtesy, Eleanor had invited Matilda to come to England with her and Henry, but she had declined, much to her daughter-in-law’s relief.

“I will never set foot there again,” the older woman had stoutly declared, “not after they insulted me so horribly, and drove me out—me, their rightful queen!”

Eleanor had heard that it was Matilda’s insufferable haughtiness and arrogance that had driven the English to abandon her cause, but she said nothing of this.

“If you change your mind, madame, or even if you come only for the coronation, you will be very welcome,” she said courteously, then turned to receive a travel-weary messenger who had just come from Henry.

“Is my lord on his way?” she asked.

“No, lady, he is besieging a castle.”

“What?” Eleanor could not believe her ears.

“Lady, he says he must teach his rebels a lesson, and will not be deterred from his purpose, neither by the news he is to be a king, nor by pleas for him to come quickly. And he sends also to say that, when he is victorious in the Vexin, he must put his affairs in order elsewhere before joining you.”

“He speaks sense,” Matilda ventured to say. “There is no point in going to England and leaving unrest in Normandy. England can wait a bit. Archbishop Theobald is a sound man, and is keeping things in order. By all accounts, the English are pleased that Henry is now their king, so we can expect little trouble there.”

“I just wish he were here with me, to share this triumph,” Eleanor said wistfully, rubbing her aching back. She turned back to the messenger. “Is my lord in good health?”

“Never better, lady,” the messenger replied cheerily, and relief coursed through her. That was one blessing, at least. She dismissed the man, then summoned her seamstress.

“You should rest, Eleanor,” Matilda said. “Remember your condition.”

“Did you, madame?” Eleanor asked.

The Empress had to smile.

“No, I was not very good at heeding the advice of my women, or the midwives,” she admitted. “Pregnancy was a great trial to me. Once I had borne Geoffrey three sons, I told him that was it. No more.” Her tone grew cooler and faded. Saying Geoffrey’s name had reminded her of how Eleanor and Geoffrey betrayed her, and of the reason for it. She was sage and just enough to admit that it was partly her fault, but she found it hard to forgive. Geoffrey had been her husband, and they had both dishonored her by rutting together. Yet she had come to concede that Eleanor had dignity and intelligence, and she was aware of a grudging admiration for her. She had made Henry the greatest prince in Christendom, this errant daughter-in-law of hers, and she would make a fine queen. That was enough to earn Matilda’s acceptance. But she knew she would never, ever like Eleanor, or approve of her—that much was certain.

When Henry did finally return, he found his wife, his mother, and the whole court immersed in a flurry of preparations for the journey to England.

“What’s all this?” he asked, astonished, coming into Eleanor’s chamber at noon with a sore head, after a night spent celebrating his accession with his barons, then his joyful reunion with his lady. There, on the bed, on the table, on stools, and on every available surface, were heaped piles of clothes, fine garments of silk, linen, and wool, many of them richly embroidered, gowns, bliauts, cloaks, chemises … Red-cheeked damsels were hastening to and fro, stowing some of it away in chests or adding even more items to the piles.

“We are packing.” Eleanor was swirling about before her mirror in a rich mantle lined with ermine. Henry looked at her admiringly as he came up behind her.

“I see you are dressed like a queen already,” he complimented her, pulling her hair aside and kissing her on the neck. “We make a handsome couple, eh?” he added, looking at their joint reflection.

“If you would take the trouble to dress a little more like a king, we’d make a very handsome couple,” Eleanor said tartly as she swiveled out of his grasp, then put the mantle into the arms of Mamille. Henry looked down ruefully at his hunting clothes; he rarely wore anything else, and only donned state robes when it was necessary to impress on formal occasions. The riding gear was clean and of good cloth, but mended in places. He had wielded the needle himself, as Eleanor watched in astonishment. “Why can’t you ask your valet to do that for you?” she had asked. “That’s no job for the Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine!”

“Why, when I can do it myself?” Henry had replied.

She secretly applauded his lack of grandeur. It made him all the more approachable. You knew where you stood with him. There was no false facade.

Henry threw himself on the bed, shoving aside a pile of veils, and began munching an apple.

“Mind those veils!” Eleanor cried, and hastened to rescue them. “Torqueri spent a long time hemming and pressing these,” she reproved. “And get your muddy boots off the bed!”

Crunching, Henry amiably complied.

“Exactly how many veils are there?” he inquired, eyeing the great pile.

“Too many to count,” Eleanor said, distracted. “Florine and Faydide, have you packed my shoes?”

“All fourteen pairs,” Florine told her.

“And the forty-two gowns,” Faydide added.

“Forty-two?” Henry echoed. “You don’t need forty-two gowns.”

“I must impress our new subjects,” she answered.

“They’ll be accusing us of extravagance,” he muttered.

“The warm undershirts, madame,” Torqueri said. Henry eyed them suspiciously. Eleanor caught his expression.

“I have heard that it can be freezing cold in England,” she said. “These are to wear beneath my gowns, over my chemise.”

“For one awful moment I thought you were going to wear them in bed!” Henry grinned. The ladies giggled.

“I might yet do so, if England is as bitter in December as they say,” Eleanor warned.

“Over my dead body,” Henry growled.

“It might be!” She laughed. “How are your preparations progressing?”

“I’m all packed, and the escort is assembling,” he told her. “I am taking the usual rabble of barons and bishops—they all want a share of the booty. It’ll be hard restraining them when they get to Westminster. I had to include my brother Geoffrey, the little bastard—my mother insisted.”

Eleanor groaned. “That troublemaker? You’ll need to keep an eye on him.”

“He’s harmless enough, just a pissing nuisance. But to make up for it, my love, I have summoned your sister to join you.”

“Petronilla?” An image of a tall, fair young woman with haunted eyes and a fragile mien sprang to mind. “That was most thoughtful. I have not seen her for years. Henry, you are so good to me.”

“Since my mother is to stay here, I realized that you would be without female company of your own rank in England,” Henry explained, gratified to see her so pleased. “I gather there was some scandal,” he added lightly, throwing the apple core out of the window and reaching for a wine flagon. “I was quite young at the time, and the adults wouldn’t talk about it. Was she a naughty girl, your sister? I have heard that she is very beautiful—although not as beautiful as you,” he added quickly.

“Pour me some wine too, please,” Eleanor said, dismissing her women and sitting down on the only corner of the bed not occupied by Henry and heaps of clothing. “I need to relax for a bit.”

“Here, put that stuff on the chests and rest here with me,” Henry offered, extending his arm invitingly and winking. “You are tiring yourself. You must think of the child.”

“Which is precisely what you won’t be doing if I lie down next to you!” Eleanor chided. “Remember, the Church forbids lovemaking during pregnancy.”

“Bah!” chortled Henry. “You weren’t saying that last night, if I remember aright.”

“I don’t see any harm in it,” Eleanor said. “Neither do I see how a lot of celibate clerics, all of them terrified of women, are qualified to pronounce on such matters.”

“They’d burn you for heresy if they heard that!’ Henry laughed. “They think that sex is only for procreation and that once you’ve procreated, there’s no further excuse for doing it.”

“How little they know.” Eleanor smiled. “It may sound blasphemous, but when you are inside me, it’s almost a spiritual experience—a communion of both souls and bodies, if you will.”

“What are you trying to do to me?” Henry asked in mock anguish, pointing to the erection visibly stirring beneath his tunic.

“Control yourself!” Eleanor reproved him, feigning displeasure. “Not now, please. I’m supposed to be resting. And I was going to tell you about Petronilla.”

Henry made a face, but settled down to listen.

“It was over ten years ago,” Eleanor began, settling herself comfortably against the bolster. “My sister was only sixteen at the time, and very headstrong. She fell in love with Count Raoul of Vermandois.”

“Surely he was too old for her?” Henry interrupted.

“Yes, by thirty-five years, but it didn’t seem to matter as she was completely infatuated, as was he.”

“Randy old goat!”

“Must you always see love in terms of sex?” Eleanor made an exasperated face, but her eyes were twinkling.

“You’ve never complained.” Henry grinned, and lifted her hand to kiss it.

“Well,” she went on, appreciating the gesture, “as it happens, you are right, because Raoul was certainly deep in lust. Unfortunately, he was married to the sister of that awful Thibaut, Count of Blois, who tried to abduct me, remember?”

“As if I could forget that bastard.” Henry frowned.

“I never liked him anyway,” Eleanor continued, “and at the time, for reasons of his own, he was refusing all homage to Louis, and so to pay him back, I encouraged Raoul to seek an annulment. That wasn’t difficult, as he and Thibaut were enemies. Anyway, Raoul left his wife, and Louis appointed three bishops to annul the marriage and marry him to Petronilla. Then all hell broke loose! Thibaut took his sister’s part and complained to the Pope, and of course Abbot Bernard had to stick his nose in, telling His Holiness and anyone else who was listening that the sacrament of marriage had been undermined and the House of Blois insulted.”

“And what happened?” Henry asked.

“Raoul was ordered by the Pope to return to his wife. You should have seen Petronilla—she was beside herself with grief. But Raoul stood by her, and refused to leave her. For that, they were both excommunicated. Louis sprang to Raoul’s defense and went to war against Thibaut. He had many good reasons to, believe me. It was during that war that the massacre of Vitry took place.”

“I know about that,” Henry said.

“All Christendom does,” Eleanor sighed. “It was just awful. Louis was blamed, but he never meant for it to happen. When the townsfolk barred their gates against him, he had his men launch flaming arrows at the castle, which was made of wood. It caught fire, and the defenders perished, so Louis’s men were able to force an entry into the town. That was all planned. But the soldiers went berserk; their captains could not control them. They laid about them with swords and torches, and soon all the buildings were ablaze. In the streets, it was a bloodbath. Those people who managed to escape took refuge in the cathedral, thinking they would be safe there, poor fools.”

“Don’t tell me the saintly Louis ordered the cathedral to be fired,” Henry interrupted.

“No, he was some way off, watching in horror from a hill outside the town. It was the wind—it blew the flames toward the cathedral, and they engulfed it at terrifying speed. Fifteen hundred people died that day, women, children, the old, and the sick. It was terrible.” She turned haunted eyes to Henry.

“You saw it?” he asked, his face grim.

“No, I was in Paris, but I had to deal with Louis on his return. He was stricken. He had seen it all; he’d heard the screams of those poor trapped people, and smelled their burning flesh.” She winced. “He’d watched helplessly as the roof caved in and those wretched souls perished. He felt it was his fault, although he never intended for such a dreadful thing to happen.” She remembered him ashen-faced and shaking, unable to speak, lying sick and mute in his bed for two days. “After that, he was never the same. He was weighed down by guilt. He even cut off his long fair hair, which I had always liked, and took to wearing a monk’s robes.”