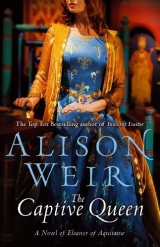

Текст книги "Captive Queen"

Автор книги: Элисон Уир

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 34 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

63

63

Bordeaux, 1186

Things had not turned out as badly as she’d feared, Eleanor reflected as she stood on the ramparts of the Crossbowman, the tall keep of the Ombrière Palace, looking down with pride on the beautiful courtyards with their tiled fountains playing in the sunshine and the gardens with their exotic plants and flowers, spread out before her like a carpet of jewels in myriad colors. It was heaven to be back in Bordeaux, her southern capital, to feel once again the summer’s heat warming her aging bones, and the soft breeze from the ocean breathing new life into her, making her feel young again, and deliciously aware that the familiar air once more held a promise of something wonderful and precious.

Thus she had felt long ago, a young girl standing on these very battlements, imbibing the heady scent of the sea and the flowers, and sensing in the gentle winds that teased her hair and her skirts some joyful anticipation of the life she had yet before her, and the love that she was sure would be hers one day.

She frowned. She was sixty-four now, and rather old to be dreaming wistfully about love. That was all behind her now. Yet some trace of yearning remained for Henry as he had once been, young and magnificent in all the vigor of his early manhood, before time and strife had soured and changed him. She did not want the man he had become, but she would always mourn the loss of the man he had once been.

To be fair, despite his thuggish means of wresting Aquitaine from Richard, Henry had since treated both Richard and herself with consideration, seeking their counsel on various matters concerning the duchy, and even allowing them each a share in its government. He had also granted them the right to issue charters. It had been Eleanor’s particular pleasure to bestow gifts and concessions on the abbey of Fontevrault, where she had stayed on her way south, exulting in its long-missed spiritual peace and tranquillity, which was such a balm to her troubled soul. One day, she had resolved, she would be laid to rest here. She could not think of a better sepulchre.

Yes, it had felt good to come home, after twelve years of exile—so good that, even now, months later she could not stop thanking God for it. Every place she visited was utterly dear to her, every old acquaintance inestimably precious. The realization that her people remembered her with affection and love had been sheer joy; and in this expansive and thankful mood, she had continued to help rule them with increasing wisdom and kindness.

Then there had come the never-to-be-forgotten day when Henry, impressed by the way she’d used the power he had given her, relented, granting her humble request and allowing her to cede all her rights in the duchy once more to Richard, leaving their son effectively ruler of Aquitaine once more. Henry’s reasoning was often fathomless, but on this occasion Eleanor suspected that his iron determination to keep Aquitaine had gradually been softened and tempered by Richard’s prolonged display of filial devotion and her own conformity to his will. Besides, it had become abundantly clear that Richard could rule the duchy better than anyone—and that it was in everyone’s interests for him to continue to do so. At Philip’s insistence, Henry had even agreed that Alys could be married to Richard as soon as the wedding could be arranged, although there was no sign of him hurrying to give orders for that. He was too busy calculating how to keep Alys for himself, or as a useful bargaining tool, Eleanor thought dourly.

Nevertheless, she reflected, looking down and smiling as she espied her damsels playing hide-and-seek amid the trees, things had improved greatly. Yet, although relations between them and their sons were far more cordial these days, she still did not trust Henry. The matter of the disposition of his empire was still unresolved, and she suspected he had plans that he was keeping to himself, which no amount of oblique probing could prompt him to disclose. She feared that the future would see a resurgence of the rivalry that had blighted their house, but knew herself powerless to forestall it.

John, clearly, was not going to live up to Henry’s high expectations. The petted favorite had been dispatched to Ireland with plain instructions to establish good relations with the Norman barons who had fought to colonize the English Pale around Dublin, and with the Irish kings who still reigned supreme in the wild and beautiful lands beyond that. But Henry made the fatal mistake of allowing John to be accompanied by his giggling young cronies, and when the native kings had come with gifts, to pay homage to their new overlord, John and his silly friends outraged their sensibilities by pulling on their long beards and making fun of their strange attire and time-honored rituals that seemed outlandish to the newcomers. To compound these insults, John had enraged the Norman barons by seizing their hard-won territories and bestowing them on his worthless intimates. Even now, John was on his way back to England in disgrace. Henry had endured enough of his crassness and appointed a viceroy to go and sort out the mess his son had created.

John was impossible. Henry had spoiled and indulged him, and they were all now suffering the consequences. In contrast, Eleanor had few worries about her daughters. Matilda and her family had at last found it safe to return to Germany, where a new Emperor ruled, one amenable to making peace with the exiles. Eleanor and Joanna were, it seemed, reasonably happily settled in their distant kingdoms. Only John and Geoffrey were giving Eleanor real cause for concern.

Geoffrey had gone to Paris, where he was even now fraternizing mysteriously with that menace Philip, and no doubt plotting some fresh mischief. You never knew with Geoffrey. Reports had it that he was as close as a blood brother to the French king. Eleanor had sometime since picked up on the fact that he was dissatisfied with being merely Duke of Brittany and wanted more. Not so long ago he thought he had Normandy within his grasp. Now he was making noises about Anjou. It was all a great annoyance to the King, and doubtless Philip was relishing abetting Geoffrey in his ambitions. Anything to discountenance Henry!

The Queen sighed. Soon, to her great sadness, she would have to leave this beloved city and travel north, for Henry was bound for England and wanted her to accompany him. They were to lodge for a time at Winchester. She did not want to go. How could she forsake the golden lands of the sunny South to waste the coming summer in a castle that would be forever associated in her mind with her long captivity?

But of course she had, as usual, no choice in the matter.

64

64

Winchester, 1186

Eleanor could have cried over the unjustness of it all! The situation with Geoffrey and Philip having become increasingly a matter for concern, she had thought to write to her son, urging him to come to England, where she hoped to talk some sense into him. But Henry intercepted the letter—she had not realized that her correspondence was still subject to the scrutiny of his officers—and his suspicious mind interpreted it as evidence that she was involved in a plot against him. After all, had she not schemed with King Louis, on that earlier, fateful occasion when her sons sought refuge and support in Paris?

Nothing she said could fully deflect Henry’s mistrust. He muttered that he accepted her explanation, but his eyes told a different story. And now she had a new custodian to replace Ralph FitzStephen, whose services had been dispensed with sometime before. She would have liked Ranulf Glanville, but he had been deployed to more pressing duties of state. At least Henry Berneval was an upright, amiable man of little charm or imagination, and he treated her with great deference and kindness; but he was her gaoler, nonetheless, and tailed her, two guards at his heels, wherever she went, even with the King in residence, which he was all that summer.

Eleanor was still smarting from the unfairness of it all when the messenger from France arrived at Winchester and she received a summons to the King’s lodgings. There, she was confronted by an ashen-faced Henry, slumped in his chair, a wine goblet lying in a pool of liquid on the rush matting, where he had evidently dropped it.

Shutting the door on Henry Berneval and his guards, so she could be alone with her husband, she knelt down before him in alarm.

“Henry! What has happened? Is it war? Has Geoffrey allied with Philip against you?”

The King looked at her dully. His eyes were bloodshot; he had been drinking a lot lately. He was quite drunk now, she realized.

“Worse. I know not how to tell you,” he mumbled, slurring his words. “Geoffrey is dead, killed in a tournament in Paris.”

“Oh God!” Eleanor cried. “No!”

A tear slid down Henry’s weathered cheek. He leaned forward and placed one tentative hand on her shoulder in a gesture intended to comfort. She barely noticed it in her distress.

“What happened? Tell me—I must know!” she wept, unable to believe that God had been so cruel as to take yet another of her children to Himself. And Geoffrey, like the Young King, had been but twenty-eight years old. Yet, unlike what happened with the Young King three years earlier, there had been no warning to prepare her, no vision vouchsafed of the bliss that lay ahead for the precious departed. This, in contrast, was a brutal shock.

“He had a fever,” Henry related, his words coming slowly and unevenly, for he too was dazed from the blow, and somewhat befuddled by alcohol. “Even so, he insisted on taking part in that damned tournament, but he was unsaddled in the mêlée and …” He could not go on.

Eleanor could imagine the scene in its full horror: the merciless sun beating down on the jousting ground, the stands packed with baying spectators, the deadly clash of swords, the ferocious, heaving fray of fighting men engaged in frenzied combat, the screams of horses, the cries of the wounded … and her son, her Geoffrey, lying there in the bloodied dust, his body broken and trampled …

It tore her apart, and she moaned in her misery, rocking back and forth on her haunches. Weeping freely, Henry drew her to him, and in that awkward embrace, and the violent tempest of their grief, they drew some small comfort from each other.

When he at last disengaged himself from Eleanor, Henry seemed embarrassed; it was as if he had somehow compromised himself by exposing his raw emotions, or betraying any need for her; as if the fragile truce between them was in danger of being subverted by the acknowledgment of a bond that had long ago been thought severed. But Eleanor did not care. She was too immersed in her sorrow to give much thought to Henry. He had comforted her when she was in desperation: she would read into his kindness nothing more than that. He need not worry.

They sat in the quiet intimacy born of years of marriage as he told her haltingly of Geoffrey’s burial in the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris.

“Philip has sent to offer his condolences and to tell me that he is building him a fine tomb in the choir. The messenger said that Philip was so mad with grief that he had to be forcibly restrained from throwing himself onto the coffin in the open tomb.” He stopped, choked.

“If I had been there, I would have done the same!” Eleanor cried passionately. “Henry, we shouldhave been there.”

“It was too late,” he replied heavily. “The hot weather …” His voice trailed off. “At least God has spared us two sons.” His voice was bitter. “And Constance is pregnant again. There may yet be an heir to Brittany.”

“She must be taking this hard,” Eleanor said, without much conviction.

“I dare say.” Henry’s ravaged face bore a sardonic expression. He knew, as well as she, that Constance would not grieve overly for Geoffrey.

“What will you do?” she ventured to ask. “Will Richard still be your heir?”

“As long as he is faithful to me,” he replied. “I have sent for John to join me. I leave for Guildford tomorrow.”

Henry had sent for his favorite son for comfort. He was abandoning her to her grief. Eleanor could not believe that he could be so selfish and callous. “Let me send for Richard,” she urged. If he could have his favorite, then she had need of hers.

Henry looked at her as if she had lost her wits. “Richard is needed in Aquitaine,” he said dismissively.

65

65

Sarum, 1188

Henry had done it at last, the thing he’d always threatened: he sent her back to Sarum, and now he was coming, presumably, to gloat on her predicament.

She supposed she could not blame him. Richard’s long-festering resentment toward his father finally drove him into the open arms of Philip, and the result had been a bloody war, with Henry on one side, backed by John and the bastard Geoffrey the Chancellor, and Richard and Philip on the other.

“Philip wants a foothold in Brittany,” Henry had said, quivering with anger and the need for action. “He dares to claim young Arthur as his ward. It wouldn’t surprise me if Constance had something to do with that. Ever since the brat was born, she’s not stopped making mischief.”

That was true. It had all begun with the naming of the baby. Henry wanted Geoffrey’s heir to be called after himself, but Constance and her Breton counselors insisted on baptizing him Arthur, in honor of the legendary hero-king who once ruled Brittany—and as a gesture to demonstrate that duchy’s desire to be free of Angevin rule. Henry had been hurt—and angered.

“I have never liked or trusted Constance,” Eleanor had warned, and he roundly agreed.

“I shall find her a new husband,” he’d declared, “one who will keep her in check.” And he had done just that: the Earl of Chester was one of his most loyal vassals, and Constance, her protests ignored, was speedily pushed into his open arms.

Then there had been the contentious matter of Alys. Again and again Philip had tried to force Henry’s hand and have her wed to Richard. When Henry had stalled, Philip had threatened to take back the Vexin and Berry and break the betrothal, demanding that Alys be returned to Paris. Then Henry had cheerily suggested that Alys be married to John instead—and at that point Philip saw red. Indeed, that proved the final straw and provoked him into raising an army and marching into Berry with the intention of seizing it—which was when Richard had deserted his father and gone over to the enemy.

Reports of what happened next had troubled Eleanor deeply, and her concerns still bedeviled her, even now in the dark reaches of the hours before dawn. Duke Richard had ridden to Paris, and there he had been so honored by Philip that they ate at the same table and shared the same dishes every day; and at night, the bed did not separate them. Those were the very words the King’s spy had written. The bed did not separate them.

Eleanor had never until now doubted her son’s sexual inclinations. Those terrible revelations of savagery and rapine in Aquitaine were enough to confirm that Richard had inherited the lust of his race. She knew that there had been women in his life, for he had acknowledged two bastard sons; her unknown grandchildren were called Philip and Fulk, Fulk being one of the favored names of the old Counts of Anjou. She grimly guessed whom Philip was named for. Of course, she would not have expected Richard to confide details of his amours to his mother, but now she realized that she had never heard any of his mistresses mentioned by name, which she had always taken to mean that they were casual encounters of the kind in which his father indulged. She realized too that Richard had never shown the slightest affection for Alys, or any inclination to wed her—but there was nothing odd about that: many men were reluctant to marry the brides chosen for them. It was what Alys represented that mattered to Richard. That was completely understandable.

But then Henry had shown her the confidential report revealing that Richard was sharing a bed with Philip. He himself had not commented; she alone had been a little disturbed by it. But what nonsense! she told herself; Richard and Philip were like brothers, by all accounts, and many brothers shared the same bed. Yet that wording was disturbing, almost as if some sinister meaning had been intended. Her imagination began to run amok. She could not bear to think of Richard preferring the love of his own sex, enduring a barren life, being cast out from and despised by the normal run of men, and risking the scandalized censure of the Church, or even charges of heresy for having offended against the natural order of God’s creation. She would not be able to bear it. He was her favorite son, her cherished one, and she wanted to see him happily settled in marriage with a brood of thriving children at his knee.

By day, she could dismiss her fears; by night, they came to torment her. She told herself she was being silly, irrational, and womanish. But the anxiety would not leave her. She dared not confide her concerns to Henry; she remembered how he had reacted to the implied suggestion that he and Becket had been lovers, all those years ago, and could imagine him exploding with wrath, and either venting that wrath on Richard or herself, or bringing the whole matter out into the open and making things infinitely worse. So she kept quiet, nursing her worries and letting them fester. Soon she was alert for any snippet of gossip that would confirm or demolish her fears. It was exhausting, wearing herself into the ground like this.

“I’m worried about what’s going on between Richard and Philip,” Henry abruptly said one day, seeming to confirm Eleanor’s worst terrors. She drew in her breath sharply, then waited in agony to see what he would say.

“I’m alarmed at what they might be plotting,” he went on, to her massive relief. “These reports of this great friendship between them concern me greatly. I want to know what lies behind it.”

So do I, she thought desperately. So do I!

“Philip thinks to sow discord between me and my sons, and thus weaken my power.”

Is that all you think it is? Eleanor wanted to ask. But Henry’s thoughts were elsewhere.

“An uprising in Aquitaine might be what is needed to divert Richard—and perhaps one in Toulouse. What say you, Eleanor? I believe I might orchestrate these risings to drag Richard away from Philip.”

“Yes!” she said, a shade too enthusiastically. “Yes, indeed!”

Henry had not noticed her vehemence. He was far too preoccupied with plotting strategies. “Then, with Richard out of the way, I’ll meet with Philip and agree to a truce. The Pope is urging a new crusade, so I’ve the perfect pretext. We can’t have the rulers of Christendom squabbling among themselves while the Turks are occupying Jerusalem.” Eleanor winced, wishing he would not be so flippant when the Holy Places were under threat; she, like most people, had been horrified to hear news of the fall of the Holy City, and applauded the Pope’s initiative. It made the quarrels among Henry, Richard, and Philip seem so petty. She had been thrilled to hear that Richard had taken the Cross, and prayed that it would divert him from plotting hostilities against his father.

But despite the truce and the plans for a crusade, the war dragged spitefully on, and Henry had again grown fearful that Richard would attempt to enlist his mother to his cause. Thus it was that Eleanor found herself commanded back to Sarum, to live once more in miserable captivity. The only difference was that she was now assigned a more spacious suite of chambers on a lower floor, which were not so open to the violent assaults of the ever-blowing winds; and she was served in more suitable state, although her damsels had been dismissed and she was once again attended only by Amaria—faithful Amaria, now grown stiff in her joints and exceedingly stout, but as plain-spoken and commonsensical as ever.

Eleanor’s heart was heavy, therefore, and her mood resentful when Henry arrived, limping pronouncedly, on a wet July day. But she was shocked out of her ill will by the change in him, a change that a mere year and a half had wrought. He had aged dreadfully and become grossly corpulent, and he seemed to be in some pain and physical distress, which was evident from the taut unease with which he carried himself.

“I came to bid you farewell, my lady,” he told her, after kissing her hand briefly on greeting. “I am bound for France, to make an attack on the French and trounce that cub Philip once and for all.”

Fear gripped her. “But what of Richard? You will not take up arms against him too?” she cried. “That would be terrible.”

Henry’s eyes narrowed. “Once, you did not think so,” he reminded her. He could never forget her treachery. “Yet calm yourself. Richard and Philip have quarreled.”

Thank God, she thought. That was one less thing to worry about.

“Richard has risen against him and driven the French out of Berry,” Henry was saying.

“Then, if Richard is for you, why are you keeping me here?” she blurted.

“I do not trust Richard,” Henry stated, “and, forgive me, Eleanor, but I do not trust you either. When this thing is settled to my satisfaction, I will set you at liberty. Until then you stay here. I have given orders that you are to be afforded every comfort.”

“I wish, for once and forever, that you could put the past behind us!” she burst out. Henry regarded her warily.

“If I cannot, you have only yourself to blame,” he said heavily.

“Henry, it’s been fifteenyears, and in all that time, I have done nothing to your detriment or my dishonor! Doesn’t that prove to you that you need no longer fear me?”

“I can’t help it,” he told her. “I dare not trust anyone now. I am suspicious of my own shadow. You, and our sons, I hold responsible for that. I was betrayed by those whom I trusted most. I cannot forget it.”

“Then there is no help for us,” Eleanor said sadly, rising and walking over to the window, standing with her back to him so he would not see how deeply his words had affected her. “At least say you have forgiven me, even if you cannot forget.” So saying, she turned around and slowly stretched out a tentative hand to him. Henry stood there for a moment, hesitating, then he too reached out, and clasped it in his familiar callused grip.

“I do forgive you, Eleanor,” he said simply. “Forgive me if I cannot forget. I thought I would never be able to forgive even, but I find myself growing old and not in the best of health, and I cannot risk going to my judgment without granting you the absolution that Our Lord enjoins in regard to those who have wronged us.” His grasp on her hand tightened. “I want you to say you forgive me too. I have not been the best of husbands.”

Eleanor was filled with a sudden sense of foreboding, as if this might be her last chance to make things right with Henry—or as right as they could ever be now. “I forgive you, truly I do,” she said, meaning it wholeheartedly.

“My lady,” he answered in a choked voice, and, bowing his head, raised her hand to his lips and kissed it again. The thought came unbidden to her that here they were, two people who had once worshipped each other passionately with their bodies, now reduced to the chaste contact of hands and lips. It was an unbearably poignant moment. What was it about this man, she asked herself, that tied her to him against all reason, when he had done so much to destroy the love she had cherished for him, and she had tried again and again to liberate herself from her thralldom?

Henry recovered himself first, raising sick gray eyes to her. “I will free you as soon as I can,” he said gruffly. “All that remains now is for me to resolve my differences with Philip, by force, if necessary,” he said, swallowing.

Eleanor looked at him fearfully. Having established this new, forgiving rapport with him, with the dawning hope of perhaps a happier reconciliation to come, she could not bear the thought of anything evil befalling him. “You are in no fit state to go to war!” she told him. “Have you looked at yourself in a mirror recently? Henry, what exactly is wrong with you? I know you are not well. Tell me!”

“It’s nothing. A trifle.” He shrugged.

“I’m not blind,” she persisted. “You are in pain.”

Henry sighed. “I have a tear in my back passage,” he admitted. “It bleeds all the time, and festers, as I cannot keep it clean.”

“Then you should not be riding a horse, still less going on long marches,” Eleanor reproved. “Can the doctors do nothing for you?”

“No, they’re useless,” he said, frowning. “I’m sorry, Eleanor, but I have to settle matters with Philip. Then I can rest and give myself time to get better. Don’t look at me like that! I’ll be all right!”

“Then may I at least give you one piece of advice, Henry?” she asked gently. “If you would keep Richard on your side, let him marry Alys without any further delays.”

Henry frowned. “I cannot,” he said at length.

“Why?” she persisted. “Is it because she is your leman?”

He looked like a trapped animal, furtive and wanting to bolt. “You know?” he asked incredulously.

“I have known for some time. Alys told me. I noticed that she was pregnant.” Eleanor paused.

“You knew, and you never said anything?”

“What was there to say, beyond warning you of your great folly and the magnitude of your sin, but I doubt you would have heeded me, of all people.” Her eyes, clear with sincerity, met his. “Henry, we were finished. The days when I lay with you wondering if another woman had enjoyed your body were long gone. I was shocked, yes, but mainly for Richard’s sake—and that silly girl’s. Alys did not come between us.”

“Richard knows,” Henry said.

“The whole world will have to know, if he marries her,” Eleanor warned. “Their union will be incestuous without a dispensation.”

“As ours was,” Henry reminded her. “You had known myfather. I often ask myself if we were cursed as a result. What else could explain all the evils that have befallen us and our issue?”

“The fact that you are descended from the Devil might have something to do with it!” Eleanor smiled. “But Henry, not everything has been touched with evil. Look at the great empire that our marriage created!”

“That too, Eleanor,” Henry said, shaking his head. “It’s been well nigh impossible holding it together; I have worn myself out trying to do so. It has caused nothing but strife and jealousies, and it will go on doing so, mark my words, maybe for hundreds of years even. Any fool should have seen that trying to unite such large domains would bring unique problems of its own, even without a cat like Philip waiting to pounce.”

He looked at the hourglass. “I must go, if I’m to get to Southampton by nightfall.”

“God go with you then, my lord,” Eleanor prayed, knowing that further protests about his health would fall on deaf ears.

“And with you, my lady,” Henry said briskly, and, planting a brief kiss on her lips this time, was gone.