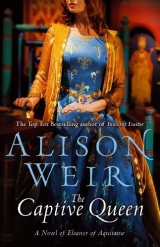

Текст книги "Captive Queen"

Автор книги: Элисон Уир

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 35 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

66

66

Winchester, 1188–1189

At first the reports that filtered through to England were encouraging. The King was winning—a great victory over the French was almost a certainty! And hot on the heels of that news came Henry’s order for Eleanor to move to the greater comfort of Winchester; yet no sooner had she gratefully settled into her lodgings there, with Henry Berneval fussing about to make sure she had everything she needed, as the King had commanded him, there came the news she had dreaded to hear. Richard had succumbed to Philip’s blandishments and deserted his father.

She wept, she raged at her son’s perfidy. But then she learned of the peace conference at Bonmoulins, where Richard, backed by the French king, had demanded that Henry name him as his heir, give him Anjou and Maine now, and let him marry Alys forthwith, without further prevarication. All reasonable requests, of course, and naturally it made sense for Richard to shoulder the burden of governing some of Henry’s domains, given the King’s state of health. But the stumbling block was, and always would be, Alys.

When Henry had refused, Richard defiantly knelt before Philip and did homage to him for Anjou and Maine; and the French, incensed at the old King’s obstinacy, attacked him and his men and drove them away from the negotiations, against all the laws of chivalry and diplomacy.

Eleanor wept again, this time for Henry’s shame and ignominy, picturing him being forced to take refuge in some crumbling, godforsaken castle, which was what appeared to have happened. Fortunately, the winter rains had set in, drawing the campaigning season to a close, and a truce had been agreed upon until Easter. Henry wrote to say that he was at Le Mans and in good health, but Ranulf Glanville, who was with him, wrote Eleanor privately to warn her that his master was ill and in low spirits.

Concerned, she wrote to Henry, pleading to be allowed to join him for Christmas, but he refused, saying that he was not planning any great festival. That was unusual in itself, for Henry had always observed the major feasts of the Church with all due ceremony and revelry, and she perceived by his answer that he was indeed unwell. She considered going to him unbidden, but that would mean evading the vigilance of the conscientious Henry Berneval and finding sufficient money and means for her journey in the depths of winter, which might prove a virtual impossibility. No, all she could do was pray for Henry’s recovery. So she spent hours on her knees before the statue of the Virgin in the castle chapel, almost bullying the Holy Mother into interceding for the King; and, for a few quiet weeks, it seemed that her prayers had been heeded.

Easter came, and with it news of another peace conference. Clearly the princes did not want all-out war if they could help it. Eleanor was on her knees again, praying for a peaceful settlement, when another letter from Ranulf Glanville was brought to her, in which she read, to her dismay, that the conference had to be postponed because the King was too ill to attend. After that, it was back to hectoring the Virgin Mary, often with tears and bribes of masses and manifold good deeds.

June, and the King was better. Eleanor’s heart rejoiced when she heard that he had met with Philip and Richard, but it plummeted again when she was told that Henry had persisted in his determination to marry Alys to John, and that Richard, maintaining that this was the first step in a sinister plot to disinherit him, threw in his lot with Philip and declared war on his father.

War. A dreadful thing in any circumstances, but when son was fighting against father, it was especially terrible. Eleanor lived her days in horrible suspense, for there could be no praying that one side would win, because there could be no winners in this conflict. It was either her husband or her son. Once, she had made that choice. She would not do so again. She gave up going to the chapel, could not constrain herself to pray. God, the protector of the just, would surely show the way to a peaceable solution. She could not believe that He had abandoned the House of Anjou entirely.

But God, it seemed, had His attention elsewhere. Philip and Richard had advanced inexorably into Angevin territory, taking castle after castle; so fearful was their might that Henry’s vassals, long alienated by his oppressive rule, had deserted him one by one. The King, meanwhile, withdrew again to the city of Le Mans, his birthplace, and when the French army appeared before its walls, gave orders that a suburb be torched to create a diversion and give him the chance to attack when the enemy’s attention was elsewhere; but he had not reckoned with the wind, which fanned the flames until much of his favored city was ablaze and Philip was able to breach its defenses. Once again Henry and his knights were forced ignominiously to flee. In yet another letter, Ranulf Glanville disclosed to Eleanor how Henry had railed bitterly against the God who abandoned him: “He warned that he would pay Him back as best he could, and that he would rob Him of the thing that He loved best in him—his immortal soul. He said a lot more besides, which I refrain from repeating.”

Eleanor could imagine it all, could see Henry seated painfully on his horse, silhouetted against the burning city, crying out his impotent anger to an unheeding deity. Her soul bled for his—and yet she could do nothing to ease his sufferings of mind or body. How could it be worth praying, she wondered, when God had turned His face from the King? Was it worth appealing to Richard? But that could—and probably would—be misconstrued. She shuddered to think what might happen if Henry found out. It might be better to get back on her knees and constrain herself to prayer.

Waiting for news was agonizing. She would wonder, a hundred times a day, if Henry and Richard might even now be confronting each other in battle. A letter from William Marshal, whom she had always accounted her champion, brought her a little relief. The King had gone north to Normandy, he informed her, and had deputed him to take a force and guard his back. Not far behind had come marching Richard at the head of a French army, and he, Marshal, had leveled his lance in readiness for battle. “The duke cried out to me not to kill him, for he wore no hauberk. I answered that I would leave the killing of him to the Devil, and had the pleasure of unseating him instead. That gave me the chance to ride away and warn the King of his approach, and thus I enabled him to avoid a direct clash of arms with the duke his son.”

Maybe it could be avoided for good if only each side would give a little, Eleanor thought as the horrendous waiting went relentlessly on, and June dragged itself into July.

It was unbearably hot. Within the sun-baked walls of Winchester Castle, Eleanor and Amaria wore their lightest silk bliautsand avoided walking in the gardens until the heat of the day had subsided. In the lands of France, it was reported, the armies on both sides were suffering miseries from sunburn, fatigue, or dysentery. Henry wrote privately to Eleanor, complaining that he was enduring torture from an abscess, and that sitting in the saddle would soon be beyond him if those damned fool physicians didn’t do something to remedy it quickly.

Hard on the heels of this came another missive from Marshal. The King had been forced to retreat to Chinon to rest, and had gone alone, with only his bastard Geoffrey for company; traveling by back roads to evade the enemy forces. “He can neither walk nor stand or sit without intense discomfort,” William wrote. “We are all worried about John, who has disappeared. It is feared that he may have been taken for a hostage by Duke Richard or King Philip. If so, Heaven help the King.” Reading this, Eleanor redoubled her prayers, beseeching God and His Mother to hear her. Let there be peace, was her earnest cry.

She was listless, not knowing how to fill the hours of waiting for the next letter or report. It took a fast courier up to five days to cover the distance from Chinon, depending on the Channel winds, so anything could have happened. Amaria tried to entice her to games of chess or thinking up riddles; she went to market and bought embroidery silks in the brightest hues, hoping to inspire Eleanor to make new cushions or an altar frontal; she had Henry Berneval send for minstrels, to while away the evenings, and she spent hours herself in the kitchens baking exquisite little cakes to tempt her mistress. But none of these pleasant distractions could alleviate the Queen’s fears or anxieties.

Having little appetite, Eleanor lost weight. She looked drawn and her skin took on an ethereal quality. She was sixty-seven, but she knew without vanity, when she peered in her mirror, that she appeared and felt younger; her graying hair was hidden beneath her headdress and veil, her fine-boned face was only delicately etched with lines, and she had the energy of a woman half her age. That restless energy was pent-up now, surging within her breast; she was desperate to be at the center of affairs, not cut off from them here at Winchester. If she had her way, she would be riding into battle with the rest of them, like the Amazon that she had once pretended to be, long ago, on that distant plain of Vézelay, when they had preached the fatal crusade that ended in disaster for both the Christian hordes and her marriage to Louis. She had been young and reckless then, and afire to show off her crusading zeal in the most attention-seeking way possible; and she would unhesitatingly take the field again, for real this time, if given the slightest chance. But, of course, it could not be: she was a woman, and a prisoner, and all she could do was wait here for news. Wait, wait, wait! They could carve those words on her tomb: She waited.

There had been another summit meeting between the chief combatants. Eleanor had the news from both William Marshal and Ranulf Glanville. The King, she learned, had dragged himself from his sickbed toward Colombières, near Tours. On the way, complaining that his whole body felt as if it were on fire, he had been forced to rest at a preceptory of the Knights Templar, and sent his knights ahead to tell Richard and Philip that he was detained on account of his illness. But Richard had not believed it. His father was feigning, he insisted; he was up to no good, plotting some new villainy; they should not trust his word.

When news of this was carried back to the King, ill as he was, he had had his men prop him up on his horse, then rode in agony through a thunderstorm to the place where his enemies waited. King Philip had actually blanched at the sight of him, and, moved by pity, offered his own cloak for him to sit on. But Henry refused it; he had come not to sit, he declared, but to pay any price they named for making peace. And so he remained on his horse, his knights holding him upright. He had looked ghastly.

Philip’s compassion had ended there. He laid down the harshest terms. Henry must pay homage to him for all his lands. He must leave his domains—even England, which Philip had no right to dispose of—to Richard. He was to pardon all those who had fought for Richard. He was to give Alys up to Philip at once, and agree to Richard marrying her immediately after the planned crusade. And, as further tokens of his good faith, he was to pay a crippling indemnity and surrender three of his chief castles to Philip.

Henry agreed. He gave in without any argument, and wheeled his horse around preparatory to riding away. But Philip stopped him and demanded that he give Richard the kiss of peace. Henry had done so, his manner frosty, his eyes as cold as steel, and when the distasteful deed was accomplished, and Richard had the grace to look suitably chastened, Henry said to him: “God grant that I may not die until I have had a fitting revenge on you.” By then blood was seeping out of his breeches and down his horse’s rump, and he had to be lifted from his horse and carried back in a litter to Chinon.

Eleanor laid the letters on the table. Her thoughts were in turmoil. The peace she had prayed for, and the securing of Richard’s inheritance, had been agreed upon, but at what cost? The utter subjection and humiliation of a sick king who was too ill to fight back. Would to God it had been done in any other way! She would even have preferred Henry and Richard to have met in battle and have the differences between them resolved in a fair fight, whatever the dangers, rather than this. To know that Henry, whose empire stretched from Scotland to Spain, had been brought so low, with his pride cast in the dust, was unbearable. He had been a strong king, a respected king, even a great king—and now he was a defeated king. And he was laid low with this pitiful complaint, poor wretch. How her heart ached for him.

But there had been that threat he had uttered. He wouldhave his revenge on Richard for this, never doubt it. Almost she was glad that he was confined to his sickbed. How could there ever be real peace between her husband and her son after this? And yet … Her thoughts winged back to the aftermath of that earlier rebellion that she herself had helped foment. He had forgiven his sons then, after all their treachery. Hugh of Avalon, that wise, saintly man, had said that those whom Henry had loved he rarely came to hate. It was no less than the truth! She must hold on to that, she told herself, as she waited—waited again—in suspense to see what would happen next.

For a week or so there was no news. Of course, she knew she should not expect any yet. Henry was resting up at Chinon, waiting for that abscess to heal. Ranulf Glanville, having some business in England, came to see her, but he could tell her nothing that she did not know, as he had left Anjou some time before.

The weather turned, and became unseasonably changeable. Hailstones were clattering against the castle walls on the day Henry Berneval knocked at the Queen’s door and found her measuring lengths of linen with her maid. Eleanor looked up. Something in the custodian’s face checked her smiling greeting. It seemed ominous that he had brought Ranulf Glanville with him, and Ranulf’s mournful expression gave her further cause for alarm.

Berneval bowed low, lower than she had ever seen him bow.

“My lady, I bring grave tidings,” he told her in a choked voice. Eleanor rose and stood before him, quiet and dignified, bracing herself to hear the worst. But what could the worst be? Did it concern Henry, or Richard—or one of her other children?

“My lady, I grieve to tell you that the Lord King has departed this life,” Berneval said quietly. “He died at Chinon four days ago. My lady, I am so very sorry to have to give you this news.”

She supposed she had half expected it. Henry had been ill and not getting better. But that he was dead, that vital autocrat who had bestrode half of Christendom, her husband these thirty-seven years, God help them both, seemed inconceivable … But as she stood there, trying to understand and accept her loss, the great bell of the cathedral started tolling in the distance, and other churches nearby in turn picked up the dread message, signaling to all England that its king was no more. Fifty-six chimes in all, one for every year of the King’s life … That ominous sound would be heard across the length and breadth of the land, as word spread of Henry’s passing.

“Do you know what happened?” Eleanor asked.

“No, my lady. We had the news from the carter who came up from Southampton. All he knew was that the King had died at Chinon. No doubt messengers will come soon with further tidings.”

Eleanor said nothing, but stared unseeing through the window, dry-eyed, her mind conjuring up the image of a magnificent young man with a straight, noble profile and unruly red curls, who had swept her off her feet, bedded and wedded her, to the scandal of all Europe. Henry had been so vigorous, so lusty! It was impossible to comprehend that all that vitality was now dust, that the virile hero who had shared with her such passion and, later, such blistering discord, was gone from her forever.

Occasionally, during these sixteen difficult years of her confinement, and even before that, when their marriage was crumbling and seemingly beyond redemption, there had been times when she sensed they might put all the pain and betrayal behind them and salvage some spark of their former ardor, some semblance of the close affinity they once shared; but the moment had never been right: always, some fresh trouble intervened. And yet, when she had taken what was to be her last farewell of Henry—a year ago, now—and they readily extended their forgiveness to each other, and were kind together for once, she had truly believed that some real chance of a reconciliation lay in the future. And now it was not to be. The realization should have broken her, but she only felt numb.

Amaria’s face was set in stone; the two custodians still stood before their queen, respectfully unwilling to intrude on her silence. Beyond the windows, the bells clanged mournfully. Soon they would ring out in rejoicing for a new ruler and life would move on, consigning Henry FitzEmpress to history. It was then that Eleanor realized that Richard was now King of England and undisputed ruler of the mighty Angevin empire. The realization brought a mixture of triumph and pain. If only her beloved son’s rightful inheritance had come to him in any other circumstances than these, with his father dying while they were so bitterly at odds.

She had been plunged suddenly into mourning, but even so, she knew she had more than one cause to rejoice, and she looked every inch the Queen as, her voice steady, she addressed her gaoler. “Master Berneval, I command you, in the name of King Richard, to set me at liberty at once.”

Berneval had been wondering if he dared free her without a mandate. The late King had commanded him to keep her secure until he received further orders, and he’d carried out those instructions faithfully. He was unsure now how to respond, and looked helplessly at Glanville for guidance.

The latter did not hesitate. “It is well known that King Richard has much love for his mother, and, bearing in mind his fearsome reputation, it might be as well to obey the Queen’s just command,” he declared. At that, Henry Berneval fell to his knees, detached the keys from the ring at his belt, and laid them in Eleanor’s outstretched hands. She bestowed a warm look of gratitude on Ranulf.

She was free, yet her freedom was an empty thing in such circumstances, and she had no desire to go anywhere. Again, she must wait on developments.

“I pray you will attend me until the King comes,” she said to both men. “And now, I desire only to go to the chapel and pray for the soul of the King my late lord.”

Later that day, William Marshal arrived, soaked to the skin after his breakneck ride to bring the news of King Henry’s death to the Queen, along with King Richard’s orders for her release. He was astonished, therefore, to find her already at liberty and waiting to receive him at the castle doorway, with a nervous Henry Berneval and a respectful Ranulf Glanville at her side.

Eleanor, garbed in her black widow’s weeds and a wimple crowned with a simple golden circlet, greeted Marshal with a smile, putting on a courageous mien and extending her hand to be kissed.

“Madame, I am overjoyed to see you free,” he told her, thinking she looked more the great lady than ever. “King Richard was most anxious that you should not be held captive any longer than necessary. He has much need of you at this time.”

Henry Berneval relaxed. He was not going to be censured for disobeying his instructions. That terrifying man who was now his king would be grateful to him for anticipating his orders. He was indebted to Ranulf Glanville for his wise counsel.

“We are just about to eat, William,” Eleanor told Marshal, having reverted effortlessly into her former accustomed role as royal châtelaine. “There is time for you to change and refresh yourself, and then I should be grateful if you would join me and give me all your news.”

Marshal was gratified to see that many lords and ladies had hurried to join the Queen’s hastily assembled court, but relieved to learn that he would be her guest at a private supper that night, for what he had to tell her was best recounted away from the public gaze. When it came to it, only the maid was present, the one who had attended Eleanor throughout her long captivity; also wearing mourning, she moved discreetly around the solar, serving food, topping up the wine and removing dishes, then making herself scarce.

William could not have guessed, from her calm manner, that Amaria was beside herself with exultation that her mistress had been freed from her captivity, and from her long purgatory of a marriage. As far as Amaria was concerned, the Queen was better off without that bastard to whom she had been chained in wedlock—“chained” being an apt word—and she was glad that the good Lord had called King Henry to his reward. She knew what she would have liked to reward him with! Yes, she was wearing black, but only out of deference to custom. As soon as King Richard came, she was buying herself a fine scarlet gown!

“Tell me what happened,” Eleanor said, when she and William Marshal were alone.

He had been dreading this moment. Yet she must be told.

“The King was in a terrible state when we got him back to Chinon. He felt his humiliation deeply, and kept cursing his sons and himself, rueing the day that ever he was born. He uttered dreadful blasphemies. He asked why he should worship Christ when He allowed him to be ignominiously confounded by a mere boy. He meant Richard, of course.”

“I cannot bear to think of his state of mind,” Eleanor said, deeply moved. “He surely could not have meant those blasphemies. He was ever one to say all kinds of rash things when his temper was aroused, and then regret them afterward. What happened to Becket was a prime example. Henry suffered agonies of remorse over that.”

“He repented of these utterances too,” Marshal told her. “Archbishop Baldwin was waiting for him at Chinon, and when he heard what the King was saying, he braved his anger and made Henry go to the chapel and make his peace with God. And he did, for all that he was near fainting with pain; and so he confessed his sins and was shriven. Then he took to his bed.”

“Could not the doctors do anything to help him?” Eleanor was shaking her head. Her meat lay congealing in its gravy on her plate, forgotten.

“I doubt they could have done very much,” Marshal said, then took a deep breath. “Besides, he lost the will to live.”

“He must have been sorely grieved at Richard’s hostility, although really, he had only himself to blame for it,” Eleanor said sadly.

Marshal swallowed. “Richard had wounded him deeply. His pride was in the dust. But that was not what finished him. His vassals, vile traitors, had deserted him in droves and gone over to Richard’s side, and toward the end, they brought him a list of those traitors, so that he might know who was to be spared punishment under the terms of the peace treaty, and whom he could not trust in the future. The first name on the list was that of the Lord John.” Marshal was near to tears.

“John!” Eleanor exclaimed. “John betrayed his father? But John was his favorite, the one he loved above all his other children. Why would John have abandoned him?”

“I imagine that Richard and Philip offered sufficient inducements,” Marshal said heavily.

“Thirty pieces of silver, no doubt!” Eleanor cried. “That John, for whose gain Henry broke with Richard, should have forsaken him—I cannot credit it.”

“That was more or less what the King said. And it was at that moment that he lost the will to live. He turned his face to the wall and dismissed us, saying he cared no more for himself or aught for this world. Then he fell into delirium, moaning with grief and pain. His bastard Geoffrey kept watch over him, cradling his head and soothing him. At the last, Henry cried, ‘Shame, shame on a conquered king!’ and fell unconscious. He died the next day without having woken again.”

It had been two days now, and Eleanor had not yet wept for her loss. The numb feeling had persisted, yet she had been conscious of a great tide of emotion waiting to engulf her. Now it broke forth, and she bent her head in her hands and sobbed piteously while Amaria hastened to hold her tightly, and Marshal, unmanned by this display of grief to the point of weeping himself, placed a tentative hand on her heaving shoulders.

He would not tell her the worst of it, he decided. She had enough to bear without that. Of course, she would find it out eventually, but by then she would hopefully be stronger.

He himself had stayed at Chinon only to hear mass and make an offering for his late master’s soul; he knew he had to make all speed to convey to King Richard the news of his father’s death. But after a hurried dinner, when he went to bid a final farewell to his old master before taking the road north, Marshal had been shocked by what he found, for King Henry lay there naked, with even his privities left uncovered, and the room was bare of all his effects. It would have been his servants, he deduced afterward, discovering that they had fled. They must have invaded the death chamber the moment Geoffrey left it, and, like scavengers, stripped the body and stolen all the dead man’s personal belongings, even his trappings of kingship.

In a fever to be on his way, Marshal had enlisted the help of a young knight, William de Trihan, and together they made the body decent and laid it out for burial. They had shifted as best they could in the circumstances. A laundress found them a filet of gold embroidery to serve in place of a crown, and they managed to find a ring, a scepter, and a sword, and some fittingly splendid garments, including fine gloves and gold shoes. Marshal shuddered at the memory, for the body was not a pretty sight, and this last duty had been a great trial for both himself and de Trihan. It was high summer, and hot, and the King had been suffering from a noisome complaint …

No, he would not tell Eleanor any of this. She was still crying, her head against Amaria’s ample bosom, but the storm of her weeping had subsided now, and she was recovering herself, taking deep, gasping breaths. It was a relief to know that she couldweep, he thought. It was a significant step on the hard road to coming to terms with her loss and the tragedies that had surrounded it. No doubt she would weep again, many times. But she would heal, for she was strong. She had weathered many tempests in her time, and this latest one would not crush her.

“Forgive me,” Eleanor said, sniffing. “I am forgetting myself.”

“Not at all, my lady,” he assured her.

“If anyone’s entitled to do that, it’s you!” Amaria said tartly, but with affection. William Marshal noted, and approved, of the familiarity. It was good to know that the Queen had someone like this sensible, homely woman to help her through this difficult time.

Eleanor reached for her goblet and took a gulp of the sweet vintage it held.

“That’s better,” she said, essaying a weak smile. “You have seen the King?”

For an awful moment, Marshal thought she was referring to Henry, but then realized she meant Richard.

“Yes, my lady. I brought him the news of King Henry’s passing.”

“And how did he take it?”

“He hastened to Chinon and bade me ride with him there. When he looked down on the late King’s body, his face was unreadable. I could not tell if he felt sorrow or grief …”

“Or even joy or triumph!” Eleanor put in. “I know my son, as I know myself. I am sure he would have experienced very mixed feelings.”

“I am sure of that too,” Marshal agreed. “He did pray awhile before the bier.” He omitted to add that no sooner had Richard gotten to his knees than he was up again, much to the disapproval of many who saw it. And there was no way that he would tell Eleanor that, as the new King rose to his feet, black blood began to flow from the nostrils of the corpse. Or that there were gasps and cries of horror from the observers, who later voiced the firm opinion that Henry’s spirit was angered by his son’s approach and hurried prayers. It had been a ghastly thing to witness, and Marshal still shuddered at the memory of it.

Still, he could tell Eleanor how Richard, no doubt belatedly racked by guilt, had been weeping and lamenting as he followed the body to Fontevrault, which the new King deemed a more fitting resting place for his father than Grandmont, where Henry had long ago expressed a wish to be buried.

“Is that where he lies?” Eleanor asked.

“Yes, my lady. They laid him to rest in the nuns’ choir.”

“It is more fitting than that austere abbey at Grandmont,” she observed. “Richard could not have chosen a better sepulchre, for Henry loved Fontevrault. That is where I myself mean to be buried when my time comes. Has Richard said anything about raising a tomb to his memory?”

“Yes, my lady. Already, he has sent for masons and commissioned an effigy to lie upon it.”

“It seems strange,” she brooded, “that a man to whom many realms were subject should be brought, in the end, to lay in a few feet of earth. Yet it is our mortal lot, and it does us good for God to remind us of the narrowness of death. Yet a tomb, even a fine one, hardly seems to suffice for a man like Henry—for whom the world was not enough.”

She smiled at him, all trace of her tears gone. “Forgive me, old friend. I am pondering aloud.”

“Your pondering was very profound,” he told her, returning the smile. “You are a great philosopher, my lady.”

“Ah, but I never benefit from my own wisdom, William!” She sipped the wine again and reflected. “There was much I did not like in Henry. He could be oppressive and unjust, and his morals were appalling. I hope he repented at the last. I should hate to think of him suffering the torments of Hell for his sins.”