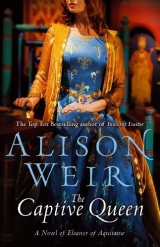

Текст книги "Captive Queen"

Автор книги: Элисон Уир

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

She fought back tears, angry with herself for allowing sentiment to get the better of her. Why must she continually chase this fantasy of re-creating the past, when the past had probably never been as good as she remembered? Even Henry had told her that, in his usual brutal fashion. We can never go back, she said inwardly to herself. There will be no more second chances for us. We are different people now, shaped and honed by our experiences, with scars that even time cannot heal. Where there was love, there can now only be hatred. Henry and I seem fated to destroy the good in our lives, and we will no doubt end up destroying each other. What happened to us, she cried silently, that we should have become such enemies?

“What is troubling you, sweet lady?” her new lover asked suddenly, snuggling up to her under the heap of furs. So emotional did Eleanor feel that she poured out the whole sorry tale of the rift in her family, even confessing how she had written to Louis.

“Some might call it treason, but truly I did not intend it that way.”

Raymond was silent for a moment. “I understand,” he said at length, “although many would not. Yet I think you are right to support your sons.”

“I suppose this night is another betrayal.” Eleanor smiled sadly. Her lover immediately sat up, his black-haired body lean and muscular in the candlelight.

“Don’t tell me you have never lain with another,” he exclaimed. “You, with your reputation.”

“This is the first time since I married my lord,” Eleanor confessed. “And the first time I have known a man in more than two years.”

There was a disconcerting pause.

“Why me, then?” Raymond seemed shocked.

“Nothing could have seemed more right at the time,” she told him, fearing that things were going badly wrong.

“But I assumed that you and the King had long had an arrangement to go your own ways in such matters. The way you flirted with me, and led me on … I thought he knew you had amours.” Already, he was moving away from her in the bed. “God’s blood, what have I done? I swore fealty to my overlord today, and here I am, already breaking my oath, and dishonoring my suzerain by bedding his wife. And you let me! My lady, you talk of betrayals, but it seems to me you know not what the word means. Yes, this isbetrayal—and you are to blame!” With that, Raymond leaped from the bed, pulled on his robe, and held open the door. Furious and ashamed, Eleanor struggled into her gown, threw her cloak over it, and swept past him, her cheeks burning.

“I will say no more of this, on my honor,” he called after her.

“Who are you to talk of honor?” she muttered under her breath.

–

Having crept back to her bower and woken her sleeping ladies, explaining that she had been kept late with her lord—and how true that was!—Eleanor lay sleepless, hating herself for what she had done, and knowing in her heart that after all these years of fidelity, she had now broken most of her marriage vows, and humiliated herself before a man who was one of her vassals. Worse still, she had revealed to him dangerous secrets. Could she count on Raymond to keep his word? Would he say no more of it, as he had promised? He would know that concealing treason was almost as bad as committing it. And if Henry found out any of this, his vengeance would be terrible; she knew it. She lay shaking in her bed, just thinking about it.

She was filled with self-loathing, yet she hated Henry more, for having been the cause of this unholy mess. And she hated Raymond too, for sinning with her and then holding her to blame. Yet deep inside her, she was secretly pleased that she’d had her small revenge on her husband—even if he never got to hear of it. It would be her private triumph, proof that she could fight back—and that she still had what it took to seduce men, despite the cruel things Henry had said of her. And she was still convinced that she was right to take up her sons’ cause, and that, if necessary, force—and any other means possible—must be used to make the King see reason.

Henry looked up from his book—it was a favorite, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, and he was in the habit of reading it again and again because it contained the stirring stories of King Arthur, which he loved. Today, Geoffrey’s history was affording him a brief refuge from the maelstrom of troubles that surged around him, so he was irritated to hear a knock at the door.

“Enter!” he barked, and Count Raymond of Toulouse came in.

“Sire? I was told I might find you here. Might I have a private word with you?”

Cursing inwardly, Henry laid down his book. “Sit down, my lord,” he invited grudgingly. Raymond obeyed, then sat there, looking uncomfortable—and curiously flushed.

“Yes?” Henry prompted.

“Sire,” the count blurted out, “the court is busy with gossip, and I am hearing strange things that I think you should be told. May I speak freely?”

Henry regarded him warily, but he believed Raymond to be a man of honor who surely would not speak lightly. “Pray do,” he said.

“Then I advise you, Lord King, to beware of your wife and sons!” the count said earnestly. To his consternation, Henry burst out in harsh laughter.

“Do not concern yourself,” he rasped. “My sons are headstrong and led astray by those around them who preach sedition. My wife is a fond and foolish mother who should know better than to indulge them, and who has corrupted their minds with folly. This is not news to me, although I thank you for your care for my safety. But never fear, the situation is under control.”

He dismissed Raymond, who departed in evident relief, but when he was alone once more, Henry fell to brooding. Was Eleanor up to something? He did not think, after his threats, that she would go so far as to privately involve Louis—anyway, the Young King had done that openly, quite brazenly, in fact. He did not believe her capable of such perfidy, or of forgetting her nuptial vows.

It was his sons who were the culprits in this. In their rash ambition, they posed the greater danger. He was haunted by a prophecy of Merlin, which he had read in his book: “The cubs shall awake and shall roar loud, and, leaving the woods, shall seek their prey within the walls of cities. Among those who shall be in their way they shall make great carnage, and shall tear out the tongues of bulls.” Were the cubs that the seer had foretold his own sons?

He would not wait to find out. They must be stopped, and now. Briskly, he gave orders that certain knights of the Young King’s household be sent away; they, he believed, had been dripping sedition into his boy’s ear. To the latter’s howls of protest, he remained deaf.

The gathering broke up. The kings returned to their kingdoms, the counts to their domains. Henry himself planned to go north with Eleanor and their sons to Poitiers; when he had set the affairs of the duchy in order, he would press on to Normandy. The Young King he would take with him. He would not let the boy out of his sight. He would make sure there was not the slightest opportunity for any intrigue.

“I am not a child!” Young Henry had once shouted.

“Then stop acting like one,” his father said tartly. “Then I might begin to take you seriously.”

Henry genuinely trusted that his eldest son was the cause of all the present trouble, and the one to be watched. Richard could safely be left with Eleanor, to share control in Aquitaine. Kept apart from Young Henry, Richard would be harmless, he was convinced. Geoffrey he would summon, to keep them both company, and to divert Richard. And so, with his house in order, or so he believed, he soon departed from the duchy and dragged his seething heir off to Normandy.

46

46

Poitiers, 1173

Young Henry had escaped! Eleanor shook—she knew not with joy or fear—when she heard the news. He had endured his father’s vigilance as far as Chinon, clearly aware that he would soon be breaking free of it. Then he had stolen out of the bedchamber that Henry insisted they share, bribed the guards to lower the drawbridge, and ridden for Paris as if the four horsemen of the Apocalypse were at his heels. In vain did Henry send men in pursuit, and soon it dawned on him that his son’s flight had been planned down to the last detail, no doubt with the secret connivance of King Louis.

One day, and that not far distant, she knew that men would point the finger at her, accusing her of being Young Henry’s accomplice, yet she was as astonished at his escape as the rest of the world, and holding her breath to see what would come of it. She could not but rejoice that he had escaped his father’s repressive vigilance, which had become so destructive, and prayed that Henry would now see sense. She had lost all patience with him.

She sent relays of messengers secretly to Paris. She had to know what was happening. They brought back momentous news.

“Lady, King Louis and the Young King have pledged themselves to aid each other against their common enemy.” That could only be Henry, she realized, although the sweating man on his knees before her had not dared to say so.

“Lady, the King has sent a deputation of bishops to Paris to ask the King of France to return his son. When King Louis asked, ‘Who sends this message?’ he was told it was the King of England. ‘The King of England is here!’ the French King said. ‘But if you refer to his father, know that he is no longer King. All the world knows that he resigned his kingdom to his son.’” Eleanor could not resist a smile at that; she had not known that Louis had it in him to throw down the gauntlet in this manner.

“Lady, the Lord King is preparing for war; he is looking to the safety of his castles and his person. Many of the barons of England and Normandy have taken the Young King’s part and declared for him!”

This was becoming serious.

“What of William Marshal?” Eleanor inquired. That wise man of integrity: how would he view all this?

“He is for the Young King.”

War! Eleanor could not believe that things had gone this far. Louis was making threats, Henry’s barons were rallying to arms, and his sons were chomping at the bit to teach him a lesson. And suddenly, with the malevolent Bertran de Born at his side, the Young King materialized in Poitiers, hurriedly embracing his mother.

“I am come in secret,” he told her. “I need your aid, and that of my brothers.”

“Tell me truly, my son,” Eleanor asked seriously, “what you hope to gain from taking up arms against your father.”

“I thought you supported me!” he flared.

“I do; I believe you have a just grievance. But we all need to be clear what the objective is. Do you intend to force the King to share his power with you, or do you mean—as report has suggested—to overthrow him and rule in his stead?”

“Would it make a difference to your supporting me?” Ah, she thought, so he does understand the moral issue at stake.

“It might have done once,” she said bitterly, “but your father has since forfeited all right to my loyalty. I am as a widow; he has insulted and abandoned me, and he has treated you, his sons and mine, with contempt—and I will not stand by and allow it. A rotten branch must be cut off before it infects the healthy tree.”

“You are prepared to go that far?” Young Henry was staring at her in amazement.

“Yes,” she told him. “Your father has forced me to make a choice between my loyalty to my husband and king, and my desire to protect the interests of my children. I am a mother. There can be no contest. Whatever love and duty he once had from me, as of right, he has killed, stone dead.” She stepped forward and hugged her tall son.

“What has he done to you?” he asked angrily.

“He struck me, that you know. I do not care to go into the rest.”

“You do not need to,” the Young King fumed. “None of us are blind. We know about the FairRosamund.” The words were spat out with a sneer.

“It seems I was the only one who didn’t,” Eleanor said lightly. “But now we must forget about all that, and discuss this war with your brothers.”

She summoned Richard and Geoffrey to her solar. Constance arrived too, full of her own opinions, but Eleanor shooed her away impatiently. She did not want the silly girl meddling where she had no business to. The Young King’s brothers were surprised to see him, and listened gravely, and in mounting fury, to what he and their mother had to say.

“It is up to you what you do,” Eleanor told them both. “You are almost grown to man’s estate, and I will not treat you like children.”

Richard got up and embraced Young Henry. “I choose to follow my brother rather than my father, because I believe he has right on his side.”

“Well said!” Eleanor applauded. “And you, Geoffrey, will you join with your brothers against your father the King?”

Geoffrey drew himself up to his full height; at fifteen, he was undergoing a growth spurt, but he would never be as tall as Young Henry and Richard, of whom he was intensely jealous. Unlike them, he was dark and saturnine in appearance, and it was rapidly becoming evident that he had a character to match. He was clever with words, perhaps the most intelligent of all Eleanor’s brood, but untrustworthy and ruthlessly ambitious.

“Naturally, I support my brother,” he said smoothly. “I too am a victim of our father’s pigheadedness. I should be ruling Brittany without his endless interference.”

“Then we are of one accord,” Eleanor declared. “Yet before we go ahead and make plans, I must ask of you all if you are aware of the implications of what you are doing, for you must go into this with your eyes open. By anyone’s reckoning, it is treason.”

“Treason,” interrupted Young Henry hotly, “is a crime against the King. I am the King, am I not? Even my father cannot dispute that. And King Louis says that, in making me King, he abdicated all sovereign authority.”

“That last is open to dispute,” Eleanor said, “but it will serve for now. You do realize you are effectively declaring war on your own father, to whom you owe love and obedience?”

Geoffrey shrugged.

“Do you not know it is our proper nature that none of us should love the other? We came from the Devil, remember? So it is not surprising that we try to injure one another!”

“Our father has forfeited his right to our love and obedience,” Richard averred, his handsome face creased in resentment.

“Aye, indeed!” the Young King agreed. “So you are both for me in this?”

“Yes!” the brothers chorused.

“You must go directly to Paris, to King Louis,” Eleanor urged them. “He is your greatest ally, and will back you with military force. I will give you letters informing him and his council of my support. I will dictate them now, while you make ready.”

Within an hour she was in the palace courtyard, kissing her sons farewell and wishing them Godspeed, wondering if she would ever see them again. Their departure was supposed to be a secret, but within hours word of it, and excited speculation as to their purpose, had spread throughout the city of Poitiers, and within a week the whole province of Aquitaine was in jubilation at the prospect of an end to the rule of the hated Duke Henry. Eleanor only became truly aware of this when a troubadour, Richard le Poitevin, visited her court and played before her and her company. His words, sung in a rich baritone voice, conveyed just how strongly her subjects really felt: Rejoice, O Aquitaine!

Be jubilant, O Poitou!

For the scepter of the King of the North Wind

Is drawing away from you!

Deeply moved, Eleanor turned to Raoul de Faye.

“We cannot ignore the voice of our people,” she murmured. “It further strengthens my conviction that opposing Henry is the right thing to do.”

“I think many of us have been waiting a long time for you to come to that conclusion, Eleanor,” Raoul said with a gentle smile. She gripped his hand.

“Will you go to Paris for me?” she asked. “Will you be my envoy, and convey a personal message from me to Louis, thanking him for his support for my sons, and begging him to have a care for their safety? He will appreciate such a personal gesture, and while you are there, you can send me word of my young lords’ welfare, and perhaps contrive to have some say in making decisions.”

“I will go with pleasure,” Raoul agreed. “I will be the voice of the Duchess of Aquitaine. You may depend on me.”

Raoul had gone, but now there came a letter, bearing the seal of Archbishop Rotrou of Rouen. What business had he, the Primate of Normandy, to be writing to her, Eleanor? Then fear gripped her. Could the Archbishop have written to tell her that something terrible had befallen one of her sons? With trembling fingers she cracked open the seal and read, her jaw dropping in horror.

Rotrou had begun courteously enough: “Pious Queen, most illustrious Queen …” But then he had gone on immediately to deplore that she, hitherto a prudent wife, had parted from her husband. That was not what appalled her—she could deal with sanctimonous platitudes any day! It was the Archbishop’s accusation that she had made the fruits of her union with the King rise up against their father. It was terrible, such conduct, he fulminated, before going on to warn her that unless she returned to her husband at once, she would be the cause of the general ruin of Christendom.

He knew! Henry knew of her betrayal. He had made Rotrou, his Archbishop, write this letter, there could be no doubt of it. But how had he found out? Everything had been planned in secret. Had her letter to Louis been intercepted? Worse still, had Raoul been taken on the road and forced to confess what he knew? Worst of all, had Henry planted spies at her court? She tried to recall the names and appearances of those who had recently joined her household, and remembered that before he left, the King had appointed four of her Poitevin countrymen to her chancery. She could not think there had been anything sinister about that, but one never knew with Henry. He was a suspicious man. Of course, it might not be the Poitevins at all, but one familiar to her, who could have been suborned into turning his coat. That was a chilling thought. Yet maybe her imagination was running away with her—Louis could well have implicated her in a letter to Henry.

Shaking, she read on, casting her eyes over pious exhortations to return with her sons to the husband whom she was bound to obey and with whom it was her duty to live. “Return, lest he mistrust you or your sons!” the Archbishop cried. Well, clearly, Henry did already mistrust her and their sons. She did not believe Rotrou’s assurance that her lord would in every possible way show her his love and grant her the assurance of perfect safety. This was the man who had sworn to kill her if she betrayed him! If she did as she was bid, she might be walking straight into a trap.

The letter continued: “Bid your sons be obedient and devoted to their father, who for their sakes has undergone so many difficulties, run so many dangers, undertaken so many labors.” Might she infer, from this, that Henry did not yet know that she had sent the boys to the court of his enemy, Louis? It seemed to assume that they were still with her in Poitiers. If so, the King could not realize the full extent of her perfidy, as he would see it.

Then came the threat. If she did not return to her lord, Rotrou warned, he himself would be forced to resort to canon law and bring the censure of the Church to bear on her. He wrote this, he protested, with great reluctance, and would do it only with grief and tears—unless, of course, she returned to her senses.

With what exactly was he threatening her? she wondered, feeling a little faint. Divorce? That had once held no terrors for her, but then she had been the one to happily instigate the process. It was bound to be a less happy experience when one was the person being divorced, especially as she knew she had much to lose, including her children. And the consequences for the Angevin empire would be dire indeed.

But the “censure of the Church” sounded worse than divorce, although it might imply that too.

Excommunication. The terrible, dreaded anathema. To be cut off from God Himself, from the Church and all its consolations and fellowship, from all Christians, cast out friendless from the community, and condemned to eternal damnation. Surely Henry would never go so far? It was the thing he himself had most dreaded throughout the long quarrel with Becket.

She couldnot go back to Henry. Very soon, he would find out that she had sent their sons, and Raoul de Faye, to his enemy, Louis—if he had not learned that already. Even if she set out now, she would probably not reach the King ahead of that intelligence. And with proof of her treachery, Henry might very well carry out his threat to kill her. For her children’s sake, and her own, she dared not return to him, not even at the risk of excommunication.

It dawned on her suddenly that she was not safe here, even in her own Aquitaine. Henry might have his hands full with his sons’ rebellion, and war on all sides, but he would surely send men after her—and then what?

She must leave. She must get to Paris as soon as she could. She had never thought that one day she would be eager to seek refuge from Henry with her former husband, but now realized that Louis was the only one who could offer her protection.

She summoned the captain of her guard and ordered him to have a small escort party made ready. The fewer they were in number, the faster they could travel. Then she gathered together her ladies, Torqueri, Florine, and Mamille, the three of her women whom she loved the best, who had been with her for years, and whom she would have trusted with her life; and she told them of her predicament.

“It is your choice entirely, whether or not you come with me. If you choose not to, I am not so handless that I cannot shift for myself, so do not trouble yourselves about that. I should welcome your company, of course, but this is flight, not a pleasure jaunt, and I cannot guarantee your safety, or when you will be able to return.”

“I’m coming,” said Mamille without hesitation.

“You may depend on me,” Torqueri added.

“Did you need to ask?” Florine smiled. Eleanor hugged them all gratefully.

There was no time to lose. They packed hurriedly, taking only what was essential and could fit into saddlebags. Then they hastened downstairs and emerged into the May sunlight. Eleanor could not help looking around her at the dear, familiar surroundings of her palace and its beautiful gardens, just then bursting into bloom, and wondering when she would see it all again. But there was no time for sentiment. The horses and men-at-arms were waiting, and they had to make haste. Their departure went almost unnoticed, for they looked to all appearances as if they were off to visit a religious house or the castle of a local lord. Four men alone, watching from a tower window, registered that the duchess was leaving and that this might be a matter worth reporting to their masters.

Once clear of Poitiers, Eleanor and her party broke into a gallop and rode hard in a northeasterly direction, as if the hounds of Hell were at their heels—as well they might be, Eleanor thought grimly. She and her ladies were all expert horsewomen, and in other circumstances the ride would have been exhilarating fun, but Eleanor was in fear that they would at any moment be intercepted or ambushed. She had been so hell-bent on fleeing that there was no time to send word of their coming ahead to Louis, and anyway, no fast messenger could have covered the long distance as rapidly as they were doing now. They were bound for the Loire crossing at Tours, then for Orléans, whence it was seventy miles to Paris.

In all, more than 180 miles lay ahead of them, a daunting distance in the circumstances. Their mounts would never stay it, of course, and they would have to rely on obtaining fresh horses at towns along the way. Eleanor had brought money for that purpose. She had even remembered to thrust a pot of salve into her bag, knowing they would all be suffering miseries from saddle-soreness by the time they reached safety.

Ten miles out of Poitiers they heard the ominous sound of hoofbeats behind them, and Eleanor nearly froze with apprehension. If she was taken now, Henry could use her as a hostage for her sons’ submission, and that would be an end to all they were fighting for. The captain heading the escort swung around in his saddle, his finger to his lips, and signaled that they should slow down and walk their mounts into nearby woodland, where they could conceal themselves behind the trees. As they obeyed his orders, they could still hear the thuds of distant galloping, which seemed to be gaining on them, but as they came to a standstill beneath the overhanging branches and stayed there, holding their breath apprehensively, the noise faded, and soon all that could be heard was the rustling of the leaves and the twittering of birds.

“Let’s press on,” the captain said brusquely.

“Stay a moment!” Eleanor ordered, and turned to her three ladies. “Torqueri, Florine, Mamille: there can be no doubt that we are in danger, even of our lives. I realize that I have been selfish in asking you to come with me, for I have made you a party to treason. If we were to be caught, you would suffer for it, so I am commanding you to turn back and go home to your families until I am able to send for you.”

The ladies made to protest, and Mamille burst into tears, but Eleanor stilled them with a shushing finger. “Go, I beg of you!” she urged. “Now. Do not worry about me. I told you, I can shift for myself.”

“But, madame, you cannot travel alone in the company of men!” Florine cried, shocked. “It would not be fitting.”

“God’s blood!” Eleanor swore. “This is not a hunting expedition or a pilgrimage to Fontevrault!”

Florine dissolved in tears.

“Just go,” the Queen said to the other two. “Take her with you and comfort her. I will take care of myself, never fear. I know we will meet again in happier circumstances.” How that would be achieved she had no idea, but one must always have faith in the future.

After brief farewells, she watched them ride back along the road they had traveled, then turned briskly to the men of her escort. “Wait here a moment,” she bade them. “I will not be long.”

She pulled her bag from her saddle and carried it some way off through the trees, to a place where she could not be seen. Then she stripped off her veil, jewels, girdle, gown, and chemise and, standing there naked, bound her breasts tightly with some old swaddling bands, then pulled out of her bag some clothing the Young King had left behind and that she’d brought in case it was necessary to disguise herself: braies, hose, a tunic, leather belt and shoon, and a caped hood clasped at the neck, under which she bundled up her long plaits. Gloves and a dagger completed the ensemble, and when she emerged from the woods, having thrust her female attire under some bracken, she was confident that she made a very passable knight or gentleman. Certainly the astonished stares of her escort told her so. She suspected that they were a little shocked, for the Church taught that it was heresy for women to wear male clothing. Yet it seemed the only safe thing to do.

They rode on, pausing briefly to swallow some bread and cheese purchased from a farmstead, then made good speed through the afternoon. It was just as evening was falling, that golden dusk-time of the day that saw the bloodred sun sinking in an azure sky, when they again heard riders coming up behind. They were on a lonely road south of Châtellerault, and had been hoping to reach the town and change horses there before curfew. But now they deemed it wiser to turn aside along a hillside track shaded by trees that would provide some cover.

To their chagrin the hoofbeats followed them. They quickened their pace, but the terrain was stony and Eleanor’s horse stumbled. Looking around in dismay, she could now see the approaching party of riders, and knew without a doubt that it was Henry’s men come for her.

“Escape! Scatter!” she cried to her escort. “It is me they want. Go now, if you value your lives.” The soldiers hesitated, saluted her briefly, impressed by her courage, then cantered away. Alone, she turned to face her pursuers.

–

They had not recognized her at first. Of course, they were looking for a queen. Instead, they had been confronted by a strange knight on a white horse, holding up his hands in surrender. It had momentarily thrown them.

“Messire, we seek Queen Eleanor,” the sergeant called as they drew near. “If you help us find her, we will not harm you.”

“I amQueen Eleanor,” the knight said, and the men-at-arms gaped, appalled at seeing her so attired. If she hadn’t been in such peril, she would have found it amusing.

The sergeant recovered his equilibrium and swallowed. “Lady, I am directed to apprehend you in the King’s name for plotting treason against him,” he said gruffly. “We have orders to take you to him in Rouen.”

They were not unkind to her. They did not insist on manacling or chaining her, but rode closely on either side of her through the long ride north, one always holding her bridle, so that she had no chance of fleeing from them. At Châtellerault, they stopped briefly to buy her a plain black gown and decent headrail, then stood guard over the back room they had commandeered at an inn, so she could change into these more seemly clothes. There was no mirror, of course, and she supposed she looked a fright, but at least they let her bring some of the contents of her saddlebag, which mercifully included a comb and the pot of salve. Women’s things, harmless.

When she emerged, the men looked at her furtively, and she even detected a touch of admiration in their faces. She could not have known—or cared—that she looked quite beautiful in the simple gown and veil, with her long hair in two braids, her features drawn from anxiety but still arresting. Nor did she realize that whatever she had done to injure the King, her daring flight held in it something of the legends and stirring tales on which these soldiers had been bred. Already, her own legend was in the making.