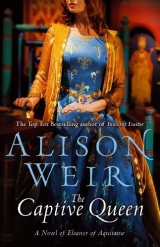

Текст книги "Captive Queen"

Автор книги: Элисон Уир

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

That night, Henry took her with even greater ardor than before, stripping away inhibitions and boundaries, and launching them on a long and sensual journey of ever-greater discovery.

“Never hold back!” he demanded. “I want everything you can give me.”

“I am my lord’s to command now,” Eleanor answered willingly, and in that moment meant it.

“Ours is a marriage of lions,” he breathed in her ear. “Did it occur to you? You have a lion as the symbol of Poitou, and my symbol is also a lion, inherited from my grandfather, King Henry of England. They called him ‘the Lion of Justice,’ but he’s supposed to have thought up the idea after receiving the gift of a lion for his menagerie in the Tower of London.”

“I like that,” Eleanor murmured, snuggling closer to him in the warmth of the feather mattress. “A marriage of lions. It has a chivalric ring to it.”

“It is apt in more ways than one, I think,” her husband observed as his arms tightened about her. “Eh, my Eleanor? We are neither of us meek and mild, but strong, audacious characters, brave as lions ourselves.”

“With you beside me, I will never know fear,” she told him, pressing her smooth cheek to his bearded one, reveling in the masculine scent of him.

“We will do well together, my fair lioness!” Henry laughed, and drew her close to him once more.

7

7

Abbey of Fontevrault, 1152

It was with a glad heart that Eleanor paid a visit to Fontevrault the month after her wedding.

“This abbey is a place especially dear to me,” she told Henry. “It was founded at my grandmother’s behest, and is dedicated to Our Lady.”

Henry nodded approvingly. He had heard of the fame of this double house of monks and nuns under the rule of an abbess, which had become a finishing school and retreat for royal and aristocratic ladies, and a haven of piety and contemplative prayer. It was a most unusual establishment in that its founder, a renowned Breton scholar called Robert d’Arbrissel, had wished to enhance the status of women, and even dared to assert that they were superior to men in many ways. Leaving that strange notion aside, Henry could understand why Eleanor thought highly of Fontevrault. He had a very good opinion of it himself. It was one of the greatest bastions of piety and faith in all Christendom.

The abbey lay by a fountain, in lush woodland on the banks of the River Vienne in north Poitou, near the border with Anjou. As Eleanor entered its lofty white church, which was distinguished by a quality of light and space seen nowhere else on Earth, and which had been beautified with simple, soaring columns and elegant triforium arcades, she felt uplifted and suffused with thankfulness. The abbess, Isabella of Anjou, who was Henry’s aunt, kissed her warmly in welcome, conducted her through the tranquil cloisters and ushered her into her spacious house, which was attached to the adjoining convent of Le Grand Moutier, where the nuns lived. Almond milk, pears, and sweetmeats were brought, and the two women, who immediately felt a mutual respect and affection, sat down to enjoy some congenial conversation.

“To what do we owe the pleasure of this visit, my lady?” Abbess Isabella asked. She was a plump, motherly woman in her mid-forties with the florid Angevin coloring, and had ruled her community for four years.

“It is a great joy to me to come to Fontevrault at this time, Mother,” Eleanor said. “I have much for which to be grateful to God. My heart is so full, and I wish to offer thanks for the great happiness He has bestowed on me in my marriage, and for making me the instrument through which unity and peace might be achieved in Christendom.”

“We must all give thanks to God for that,” the abbess declared. Intelligent and perceptive woman that she was, she was well aware of the hoped-for outcome of the duchess’s union with Henry FitzEmpress. “You will join us for dinner in our refectory afterward?” the abbess invited.

“Most certainly, I thank you.” Eleanor smiled. “But there is another purpose to my visit, Mother. After my marriage to my Lord Henry, I felt that divine inspiration was leading me to visit this sacred congregation. It feels as if I have been guided by God to Fontevrault, and while here, I intend to approve and confirm all the charters and gifts that my forefathers have given to this house. If you will have this drawn up on a parchment, Mother, I will affix my seal. It is a new one.” Proudly, she drew it from the embroidered purse hanging at her girdle and showed it to the abbess. It portrayed Eleanor as duchess of both Aquitaine and Normandy. “See, I am holding a bird perched upon a cross; it is a sacred symbol of sovereignty.”

“If I may say so, madame, wedlock suits you: you are looking radiant,” the abbess observed. “I am delighted that you have found such joy in your union with my nephew. I hear that he has ambitions to be King of England.”

“Which I have no doubt he will fulfill,” Eleanor said.

“I was in England thirty years ago, before I entered religion,” Abbess Isabella recalled. “I was married to William, the son of King Henry, who was himself son to William the Conqueror, and grandfather to your husband. They called King Henry the ‘Lion of Justice.’ He was a lion indeed! Strong and respected as a ruler, but a terrifying man, cruel and ruthless. I can never forget what he did to his grandchildren.”

“What did he do?” Eleanor asked, thrusting away the unwelcome thought that the same violent blood ran in her own Henry.

“One of his daughters defied him, with her husband, and he had the eyes of their two little girls put out as punishment.”

Eleanor shivered. “How vile. That’s too awful to contemplate. What was his son like?”

“William? They called him ‘the Atheling,’ after the old Saxon princes before the conquest. He was another like his father, proud, fierce, and hardhearted. Mercifully, I was not married to him for very long.”

“Was he the prince who drowned when the White Ship sank?”

“The very same.”

“I have heard my lord speak of his death. He said King Henry never smiled again.”

“For the King, it was a tragedy. He had no other son to succeed him. Not a legitimate one, at any rate. His bastards, of course, were legion.” The abbess’s lips twitched. “But God in His wisdom took unto himself my young lord, and King Henry forced his barons to swear allegiance to his daughter Matilda as his heir.”

“The Empress, my mother-in-law,” Eleanor supplied. “Did you ever meet her?”

“No, she was then married to the Holy Roman Emperor and living in Germany. He died later on, and she married my brother Geoffrey, but she never came to visit me. By all accounts she is a strong woman. She has certainly fought hard for the kingdom that was lawfully hers.”

“And lost,” Eleanor put in. “But my lord will reclaim it in her name. She has ceded her rights to him. The portents are good.”

“King Stephen still lives, though,” Isabella stated.

“He is hated and despised, my lord says. Those barons who would not accept a woman as their ruler are far more amenable to Henry, especially now that he has proved himself a ruler to be reckoned with. Tell me, Mother, what is England like?”

“They call it ‘the ringing isle’ because there are so many churches. It is green and lovely, and a lot like France in some parts, but the weather is unpredictable. The people are insular, but hospitable. And no, before you ask, they do not have tails, as is popularly bruited here!”

Eleanor laughed. “I never heed such nonsense!” She accepted a tiny fig pastry. “I will look forward to seeing England someday. Oh, I wanted to tell you that my lord and I have commissioned a window commemorating our marriage in the new stained glass. It is to be set into the east window of the Poitiers cathedral, that all who see it will remember where we were made man and wife.”

“A fitting gesture,” the abbess said. “And an enduring one.”

“Yet more precious to God will be my thanks and praise,” Eleanor said, swallowing the last of the pastry and rising to her feet. “If you would excuse me, Mother, I shall go into the church now. Summon your scribes, if you would. We can have the charter written out later.”

8

8

Aquitaine, 1152

“Louis has summoned us,” Henry announced, bursting into Eleanor’s solar and thrusting a parchment into her hands. Briefly, she perused it.

“This was addressed to both of us,” she said, anger rising, born of her fear of what Louis might do, and shock at Henry’s presumption. “You should not have broken the seal without my being there.”

“I am the duke,” Henry stated uncompromisingly.

“And I am the duchess!” she flared.

“And my wife,” Henry shouted. His sudden anger excited her, despite her annoyance with him. This was not the first quarrel they had had, and it would certainly not be the last, she knew that well. The only compensation was that every time, without fail, they found themselves in bed, sealing their reconciliation with passionate lovemaking.

“This is my duchy!” Eleanor insisted.

“And mine in right of our marriage. I shouldn’t have to remind you that I am the ruler here now. I’ve told you before, Eleanor, governing is man’s work, and women should not interfere.”

“You’re as bad as Abbot Bernard!” she flung at him. “You and I are meant to be a partnership. We agreed. I am no milksop farmwife to be cast aside: I am the sovereign Duchess of Aquitaine, and I will be deferred to as such! Do you heed me?”

For answer, Henry folded her in his arms and kissed her brutally. “This is your role now, my lady. I do not remember agreeing to anything.”

“How dare you!” Eleanor cried, struggling free and slapping him on the cheek. “These are my domains, and my word is law here.”

Henry recoiled. His face was thunderous, his voice menacing. “Enough, Eleanor. Leave that for now. There are more pressing matters to consider. I came to tell you that Louis has summoned us to his court”—he unscrolled the parchment and read—“‘to account for our treasonable misconduct in marrying.’”

“It’s bluster,” Eleanor declared, still angry. “He cannot do anything to us.”

Henry frowned. “I wouldn’t be so complacent. The envoys who brought this say that their master is shocked and angered. He accuses me of basely stealing his wife—”

“As if I were a chattel to be taken against my will!” Eleanor interrupted, furious.

Henry threw her a look. “Some of the French lords have even urged Louis to revoke the terms of your annulment,” he went on, “or even the annulment itself. Others want us excommunicated.”

“Words!” fumed Eleanor.

“Angry men often translate words into actions,” Henry said. “My enemies are uniting against us. Even my beloved little brother Geoffrey has declared his support for Louis. And Count Henry of Champagne, who is betrothed to your daughter Marie, is dashing off to Paris to join them. Of course, he knows very well that if you and I have a son, Marie will not get Aquitaine. His brother, Thibaut of Blois, that bastard who tried to abduct you, is also for Louis.”

“He is to wed my little Alix when she is of age,” Eleanor said, a touch wistfully. “I could wish it otherwise. He could not win the mother, so he settled for the daughter, the bastard!”

“It’s war, no less,” Henry declared. “I must leave for Normandy at once. The rumor is that Louis plans to attack it in my absence.”

“Then this is our first farewell,” Eleanor said, the last traces of her rancor evaporating. She swallowed and put on a brave smile. “I suspect it will be the first of many, given how far-flung our domains are.”

“You knew that when you took me for a husband,” Henry said gently, tilting her chin toward his face. He kissed her long and hard, all trace of annoyance gone. “It grieves me too, Eleanor, but it will not be for long. I will send Louis and all his cronies scuttling back to Paris with their tails between their legs. And mayhap I am leaving you with child …”

“Then God will have smiled upon our union,” Eleanor pronounced. “I fear it is too early to tell.”

Henry sighed. “I could have done without all this,” he growled. “I was planning to take an army across to England and settle matters there, but it will have to wait, yet again. At this rate, the English will get fed up with waiting and declare for the usurper Stephen after all.”

He kissed her again, then broke away.

“I must go,” he said briskly. “Speed is of the essence.”

The news Henry sent Eleanor by his couriers was good. Louis had the temerity to invade Normandy, but Henry advanced with such speed that several horses dropped dead from exhaustion on the road; and with devastating compunction, he laid waste that land called the Vexin on the Norman-French border and the demesnes of Louis’s own brother, Robert of Dreux.

Next she heard he had been in Touraine, taking some castles that his father left to the unfraternal Geoffrey. He was winning through. Then God Himself, it seemed, intervened. Louis, Henry wrote, had collapsed with a fever and was laid up at Geoffrey’s castle of Montsoreau. Eleanor smiled when she read that. It was typical of Louis to fall ill at such a crucial moment. She smiled even more broadly when she read on and learned that right now Henry was besieging the castle.

“The Lord Geoffrey has submitted and begged for mercy and reconciliation,” the next messenger told her, “and the King of France has given up his cause for lost and sued for peace. He has gone back to Paris.”

How ignominious, Eleanor thought. But again, typical.

After six weeks, Henry was back in Poitiers, the magnificent victor. There was a new air of authority about him; he was now the dominant power in western Christendom, and he knew it.

Wasting no time, the returning hero took his wife to bed and had his will of her vigorously and repeatedly, to her great and unbearable joy.

“I swear to you, Eleanor,” he gasped, heaving and sweating in her eager arms, “no assault on a fortress was ever so pleasurable. You yield delightfully!”

“Come again,” she breathed, raising her knees and clasping her ankles across his tight buttocks. He readily obliged, and soon had her crying out in ecstasy.

“Hush!” he panted, kissing her lustily. “Your barons will think the war has broken out again!”

Eleanor held herself in speechless stillness as waves of pleasure coursed through her. Feeling Henry inside her was sheer bliss. It had been so long … She had barely contained her need for him. But for all her delight in their joining, she was miserably aware that he was shortly to leave her again.

“When do you depart for England?” she asked a little later, when they were lying peacefully together under the single sheet. It was a warm, balmy night, and the sky glimpsed through the narrow window was indigo blue and bright with stars.

“Not until the end of the year,” Henry said.

“You’re planning a winter campaign?” she asked, surprised.

“No, my lady, I intend to use diplomacy this time. Of course, an army at my back will help negotiations wonderfully, because the English will know that I mean to deploy it if necessary.”

“This latest victory can only have enhanced your reputation, my brave Henry,” Eleanor murmured, kissing him. “The English now know what they have to reckon with.”

“The English are no fools. They need a strong king, and I’m their man. The question now is how to topple Stephen and his son without causing too much unpleasantness.”

“With any luck he will have wearied of the struggle and be eager to come to terms,” Eleanor said. “Then you can return speedily to me, my love.” She turned and twined her arms around him, rejoicing in the strength of his supine body.

“I’ll be here for a while yet,” Henry said, biting her neck playfully between words. “It occurred to me that before the autumn sets in, we should make a leisurely progress through your domains, so that you can introduce me to your vassals. The ones who are speaking to you, anyway. Of course, I hope that meets with your approval, O sovereign Duchess of Aquitaine!” He was mocking her, she knew, but she did not leap to the bait. She was too overjoyed at his suggestion.

“I should love that, Henry,” she enthused. “There are so many places I want to show you. We should start with the Limousin. It’s wild country in every respect, but so beautiful, and it will do its unruly lords a power of good to be brought face-to-face with their new suzerain. They will meet their match and more!”

“Your faith in me is touching!” Henry murmured, nuzzling her ear.

“We must go to my father’s hunting lodge at Talmont—he used to take us hawking there. It is where my gyrfalcons are bred. I will give you one, the prize of the mews. Nothing but the best for my lord! You must see Les Landes in Gascony—nothing but acres and acres of scrub, sand dunes, and pine forests, but so wild and bracing.”

“We will ride out there together, alone,” Henry promised, catching her excitement.

“The pearl of my domains is the Périgord,” Eleanor went on. “The valley of the Dordogne is unsurpassed for its beauty. There I will feed you on freshly dug truffles, which are glorious in omelettes, and confit of duck, and foie gras—the area is known for its wonderful food.”

“Stop, you’ll have me running to fat!” Henry interrupted, laughing. “My forebears were enormous.” He paused and looked down at her. “So show me all, my love … apart from your lands!” And he ducked, choking with mirth, as Eleanor rose wrathfully up in the bed and began pounding him with her pillow.

The tour had not gone well.

“Your vassals do not like me!” Henry repeatedly complained. “You, they defer to, and treat with respect. Iam regarded with suspicion!” His gray eyes were narrowed in anger.

Eleanor could not refute what he said, for it was no less than the truth. Everywhere, without exception, there had been enthusiastic cheers for her and cool receptions and studied politeness for Henry. No one had actually said anything, and mercifully there were no demonstrations, but the hostility was palpable. It made a mockery of the glorious, spacious autumnal landscapes, the sunflowers browning drowsily in the fields, the majestic rivers and spectacular crags. Henry remarked upon none of these wonders; he had been simmering with rage.

Early on there had been the awful day when several of Eleanor’s lords came to her privately after they had arrived in the Limousin. “Madame the Duchess,” one of them had said, grim-faced, “to you, we are devoted and loyal, never doubt it. But hear this: we owe Duke Henry no allegiance save as your husband.”

“He is your lord now,” Eleanor had said sternly, knowing how badly Henry would take this; “and it is my will that you acknowledge him as such, and show him the customary fealty and obedience.”

“Madame, he is a foreigner, like the French. His first loyalty is not to us, but to Normandy and Anjou, and his ambitions lie in England. Many believe he means to milk Aquitaine dry to achieve his crown.”

“He does not need to,” she assured them, springing to Henry’s defense. “He has sufficient men and resources of his own! I give you my word on that.”

She did not manage to convince them, however, and did not dare reveal this conversation to Henry. Things were bad enough, and the reluctance of her vassals to pay court to him all too plain. Inevitably, Henry’s temper had become increasingly foul throughout the progress. In vain she’d tried to distract him by pointing out ancient churches and mighty castles, and to tempt him with the fine food and abundant vintages of the region, which should have been the source of much mutual enjoyment. But it was a wasted effort. He was not going to say one good word about anything, on principle. In the end she gave up trying.

Now, having reached gentler countryside, and traversed peaceful pastures, they were before Limoges, her chief city of the Limousin, their gaily striped tents pitched outside the massive new walls, the pride of its citizens. Henry looked up approvingly at the impressive fortifications, and his mood lightened further as he and Eleanor entered the city to the unexpectedly rapturous acclaim of the people. He expressed admiration for the great abbey and shrine of St. Martial, the city’s patron, and showed a genuine interest in the Romanesque splendor of the cathedral and the exquisite, richly colored enamel plaques that he and Eleanor were given as gifts by the burghers.

That night, they were to dine in their silken pavilion beyond the walls, with the Abbot of St. Martial and the chief lords of the Limousin as guests. Eleanor’s damsels had dressed her in a beautiful green Byzantine robe that set off her red hair to perfection, and as she and Henry took their places at the high table, she’d begun to hope that her husband was feeling happier about the progress, and that things would be better from now on.

Given their warm welcome, she happily anticipated a lavish feast, and waxed lyrical about the succulent truffles produced in the Limousin, the rich game, the roast ox drizzled with sweet chestnuts, and the violet mustard. But Henry took one look at the puny duck and scrawny goose that lay on the golden platters before him and barked, “Is this all there is to eat?”

“It is all we have, lord,” the serving varlets stammered.

“Ask Madame the Duchess’s cook to come here!” Henry demanded. “This is mean fare indeed!”

Eleanor’s master cook came hastening into the pavilion, his lugubrious face crumpled with concern. He bowed ostentatiously to her, ignoring Henry.

“Lady, I am very sorry, but this is all we have. The citizens did not send the usual supplies.”

“And why was that?” Henry snarled.

“Let me deal with this,” Eleanor murmured.

“No, my lady, they will answer to me. Am I not the Duke of Aquitaine?” Henry’s cheeks were flushed with fury.

“My lieges, allow me to explain what has happened,” the Abbot of St. Martial intervened smoothly. He was a haughty man with a chill in his manner, and for all his courtesy, barely concealed his resentment of his new overlord.

Henry glared at him, while Eleanor shuddered inwardly. More trouble, she thought, and just when matters were improving.

“It is customary, I fear,” the abbot went on in his high, reedy voice, “for food supplies to be delivered to the royal kitchens only when Madame the Duchess is lodging within the city walls.”

Henry’s set expression suddenly changed dramatically. He went purple with anger. Eleanor had never seen him so enraged; was she at last going to witness the notorious Angevin temper at its worst? It seemed she was! Roaring curses on the abbot, the citizens, and—for good measure—St. Martial himself, Henry lost control and, throwing himself on the floor, rolled around yelling bloodcurdling oaths before finally falling quiet and grinding his teeth on the rushes strewn over the flagstones. The fit lasted a full three minutes, with Eleanor looking on open-mouthed, the abbot curling his lip in disgust at the prone, seething figure at his feet, and the aghast company craning their necks to get a better view.

After the worst excesses of his rage had subsided, Henry got dazedly to his feet and stood glowering at the sea of faces staring at him.

“Know this!” he cried in his cracked voice. “I, Henry FitzEmpress, your duke and liege lord, will not tolerate such blatant disrespect. Nor will my lady here.” He looked hard at Eleanor, challenging her to agree with him, and although she had been on the point of interrupting, she subsided, quelled by the menacing steel in his gaze.

“Limoges will pay dearly for this insult,” Henry announced to the silent company. “Its walls shall be razed to the ground. No one, least of all you, my Lord Abbot, will be able in future to use them as an excuse for depriving me or your duchess of our just and reasonable dues. Now you had best get back to the city and convey my orders to your people—and see that they are obeyed! Demolition must begin tomorrow.”

Eleanor watched, appalled, as the mighty abbot, who had up till now enjoyed great power and autonomy, was dismissed like an errant novice. She knew that Henry’s anger was justified, but also felt that his vengeance was overly harsh. Yet to appeal to him now would be disastrous—she must appear to be supporting him and show the world that they were united in their indignation.

Later, though, in the privacy of their tent, she burned with the injustice of it all. After they had lain silent in bed for a while, she turned to him.

“What on earth were you doing?” she asked. “People were looking at you as if you were possessed by devils.”

“Sometimes, when these rages are upon me, I think I am,” Henry muttered.

“Can you not control yourself?”

“No. Something in me explodes, and I have no power over it. Anyway, I was right to be angry. I will not be slighted like that. I will not have you slighted like that.”

“Yes, you were right,” Eleanor agreed. “No one could blame you for being angry. I just wish you could have curbed your temper a little and not made such a spectacle of yourself.”

Henry stiffened. “Don’t you dare preach to me, Eleanor!”

“I am not. I was embarrassed. And, if I may venture to say so without your biting my head off or throwing a tantrum, I think the punishment you handed down was severe in the extreme.”

Henry raised himself up on one muscular elbow. “Do you? Pah! The citizens of Limoges—and your people at large—need to be taught who is master here. Stern measures are called for. It’s called strategy, my dear.”

“Those walls are brand-new and strong, the latest in defenses. You were admiring them yourself. They took years to build, at great cost. If you force the people to pull them down, you will be hated and resented. Could you not rescind the order and think up some other punishment?”

“I would rather be hated and resented than not have my vassals fear me,” Henry declared. “How would it look, retracting my order? I would be seen as a weak man whose word is not his bond, one to be cozened and wheedled out of decisions. No, Eleanor, once my mind is made up, it is made up for good. There is no point in trying to dissuade me.”

“You might have taken counsel of me first,” she protested. “I am the duchess, after all, and these are my people.”

“You are my wife, and your part is to obey me,” Henry flared. “I am heartily sick of playing a subordinate role in this duchy. Now get on your back and learn who is master!”

No man had ever spoken to her like that, but Eleanor was too shocked to object as Henry forced her thighs apart and thrust himself between them, ramming his manhood into her with little care about hurting her. Not that it did hurt—not physically, anyway, for she usually thrilled to rough handling—but this was the first time that Henry had taken her in anger or used her body to enforce his own supremacy. Afterward, as he slumped at her side and his heavy breathing quietened, she lay there grieving, knowing that, without her being able to help it, the balance in their relationship had altered, and fearing it might never again be possible for them to come together as equals after this.

Henry, by contrast, seemed unaware that there had been a change. He was up early the next morning, pulling on his tunic and hose and splashing cold water on his face.

“Are you getting up?” he asked.

Eleanor gazed at him wearily from the pillow. She knew what this day must witness, and wanted no part in it.

He came toward her and sat on the bed.

“I am going to supervise the dismantling of the walls,” he said, bristling with determination. “I want you with me, to show that we are united in our anger.”

“No,” she said firmly. Henry snorted with impatience.

“Up!” he barked. “Get up! Like it or not, you are coming with me.” He grabbed her arms none too gently, pinching the soft flesh, and dragged her into a sitting position.

“Very well,” Eleanor said icily, realizing that further protest would only result in an undignified scuffle that she could not hope to win. She slid off the bed and pulled on her shift. “Grant me at least the courtesy of ten minutes to make myself presentable.”

Alone with her women, she asked for her black mourning gown to be brought. “That, and a black veil—and my ducal coronet. No jewels.”

“You look like a bloody nun,” Henry exclaimed when he saw her. “Why the weeds?”

“How perceptive you are!” she retorted. “I am mourning the loss of my people’s love.”

“Don’t be so dramatic,” he scoffed.

“After yesterday’s display, you are in no position to talk,” Eleanor snapped, adjusting her veil. “Well, I am ready,” she added quickly, seeing him framing a biting reply. “I suppose you are still insisting on this cruel, harsh order being carried out?”

“Come!” was all Henry said.

They emerged from their tent to a maelstrom of activity. Scaffolding was being erected, tools commandeered, and surly, glowering men—long lines of them—were being impressed to do the demolition work. Even the master masons, loudly protesting, had been given no choice. Women, and even children, were scurrying to and fro with huge baskets, or carrying messages conveying orders, while great carts stood ready to carry away the rubble. The atmosphere was subdued, the resentment of the people palpable. When Henry appeared, there were muffled curses.

He leaped up onto a large boulder and signaled to his men-at-arms to sound the alarum. The activity ceased, and hundreds of pairs of angry eyes turned to the stocky figure of the duke. Eleanor, standing miserably behind him, almost shaking with resentment, could see burning hatred in those eyes—and a desire for revenge.

“People of Limoges!” Henry cried in ringing tones. “I hope you will not forget this day, and I hope you will learn from it. When Madame the Duchess and I next visit you, I trust you will treat us with greater courtesy. And maybe you might like to rebuild these inconvenient walls so as to allow better access to your kitchens!”

There was a sullen silence. Then someone in the crowd threw a stone. It missed, but Henry was not in a forgiving mood.

“If I catch the varlet who did that, I’ll have him castrated,” he threatened. “And anyone else who thinks they can mock my justice. Now, back to work, all of you.” He jumped off the boulder and strode over to Eleanor, then grasping her purposefully by the hand, led her along the perimeter of the plateau on which the old city was built, following the line of the doomed walls. Behind them tramped his armed escort. The citizens saw them coming as they bent furiously to their task, not daring to slacken, for Henry’s anger was still writ plain upon his face. Finally, he and Eleanor arrived at a vantage point at a safe distance from the demolition work and stood there to watch, as citizens who had lavished good money and pride, not to mention the sweat of their backs and the blood of their willing fingers, building their defenses, grudgingly pulled them apart, stone by stone. As the walls of Limoges began crashing to the ground in clouds of yellow dust, Eleanor felt the destruction like a physical pain. Yet her face remained impassive, for Henry was watching her, as if daring her to protest; but she would not allow him that satisfaction.