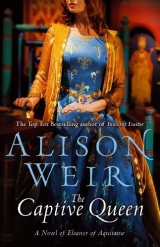

Текст книги "Captive Queen"

Автор книги: Элисон Уир

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

44

44

Chinon, 1172

Christmas had arrived. Eleanor was keeping the festival with Henry at Chinon, and their three oldest sons had been invited. The King greeted her with unexpected warmth and one of his bearlike hugs, and complimented her on her rich attire. It was the green Byzantine robe she had worn in the years of their passion, when the mere sight of her dressed in her finery had been sufficient to inflame his desire, but he seemed to have forgotten all that.

She had learned not to let herself get upset at his fitful interest in her; they were, after all, meant to be separated. She soon saw that, for all his bonhomie, put on for the season, Henry remained preoccupied with his own private demons and was impatient with everyone, and she suspected that he was building up to yet another confrontation with the Young King.

“I summoned Young Henry back from Paris,” he told her. “My spies warned me that Louis was cozening him to demand his share of my dominions. I put a stop to that immediately!”

“I am glad that our son is coming here,” Eleanor said, trying tactfully to convey to Henry that there was more to this situation than a power struggle. “I have not seen him for many months. And Marguerite has always been like a daughter to me.”

But the Young King did not come. He sent word to say that his friend, Eleanor’s warlike troubadour Bertran de Born, had invited him to his castle at Hautfort, whither Young Henry had extravagantly summoned all the knights in Normandy named William to feast with him.

Henry exploded. “God’s blood! Is there no end to the cub’s stupidity? Of all the pointless, frivolous things to do! What is he thinking of? And as for Bertran de Born, as you should know, he is a dangerous troublemaker.”

“Henry.” Eleanor laid a calm hand on his shoulders and looked directly into his purple-veined face. “Our son indulges in frivolous and pointless pursuits because you force him to. His whole life is frivolous and pointless. You have made him a king, yet you allow him no kingly power, so the whole exercise was in vain. You keep him short of money and curtail his pleasures; you insist on appointing all the members of his household. You even dictated when he could sleep with his wife, who has been ripe for the marriage bed these past two years, as we both know. Henry, before it is too late, let him be the king he wants to be. Then he can prove his true worth. He needs to cut his teeth before he can rule an empire.”

The King stared at her as if she were mad, and shook her off angrily. Then she realized that he was looking beyond her, and she turned to see Richard and Geoffrey standing there. By the looks on their faces, they heard what had been said.

“Mother is right,” said Richard defiantly. “Why will you not give us any power, Father? I am Duke of Aquitaine and Geoffrey is Duke of Brittany, but they are empty titles.”

“Richard speaks truth, Father,” asserted Geoffrey.

“Shut up!” snapped Henry. “You’re only fourteen—what do you know? Are you all in this against me?”

“In what?” Eleanor inquired. “A conspiracy? How could you think that, Henry? I am looking to the future, and doing my best to prevent a rift between you and our sons. I believe they have a just grievance.”

“Yes, we do!” Richard and Geoffrey echoed.

Henry faced them, a man at bay. “It is written that every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation, and I cannot risk that happening. I have built up my empire, domain by domain, and I have spent most of my life fighting to hold it and keep it intact. One day, thanks to me, it will be your inheritance. One day. But if I now give England, Normandy, Anjou, and Maine to Henry, Aquitaine to you, Richard, and Brittany to Geoffrey, what will I be left with? I might as well retire to Fontevrault and become a monk!”

“We ask only that you share your power with us, Father, and give us some proper responsibilities,” Richard said.

“No,” Henry told him. “You are yet young and inexperienced. There will be time enough for that when you are older.”

“Henry, when you inherited Normandy, you were eighteen, only a year older than Young Henry is now,” Eleanor reminded him.

“Yes, but I did not consort with troubadours, or feast with unworthy knights just because they bore a name that took my fancy. I had to grow up quickly, in the midst of a civil war, and I learned early on to fight in the field and pit my wits against my mother’s adversaries. Thanks be to God, our sons have never had to deal with such difficulties.”

“Even so, you have overly protected them,” Eleanor retorted. “Now you must let them be men and stand on their own feet, and give them cause to be thankful to you. Heaven knows, their demands are not unreasonable.”

“I beg leave to differ. The courier who brought Young Henry’s message was my own man. He had heard the cub boasting that he ought by rights to reign alone, for at his coronation, my reign, as it were, had ceased.”

Eleanor’s sharp intake of breath pierced the stunned silence. The two boys looked at their feet, knowing themselves defeated by their brother’s thoughtless stupidity.

“That is the kind of poison that your Bertran de Born has been dripping in my son’s ear,” Henry snarled. “I wonder where he got the idea.”

“Not from me!” Eleanor cried hotly. “That is unjust! How could you think it?”

“You always take his part.”

“That is because you refuse to see things his way.” She was in a ferment, past caring if she offended or upset him. “And now, clearly, it is too late. It is you who have brought us to this pass, Henry. You can never admit that you are wrong. Look at what happened in Aquitaine. It’s the same with your vassals all over the empire. They complain that you are too heavy-handed, too authoritarian. That’s exactly what is wrong with your treatment of your heirs, and I will not stand by and see it!”

Henry hit her, hard, across the mouth. “That’s enough!” he roared.

“Mmmm!” she cried in pain, clapping her hand to her bleeding lips. This could not be happening, she thought. Henry had been that rarity among husbands: only once before had he used violence on her, the time she unwisely taunted him about Becket—and that had been only a slap. Thus his lashing out at her now, and drawing blood, was shocking in the extreme. It was bad enough that he had struck her—worse still that he had done it in front of their sons.

Richard’s hand had flown to his dagger, and Geoffrey, equally outraged, sprang to comfort their mother. Henry glared at Richard.

“I am your king, and your father, to whom you owe all honor and obedience,” he said menacingly. “Lift one finger in anger against me and you commit treason, which I will punish accordingly, whether you be my son or no.”

“You hit my Lady Mother,” Richard replied through gritted teeth. “You are no father of mine.” And, leaving Henry glowering and muttering threats, he helped Geoffrey assist Eleanor to her bower, where her horrified damsels ministered to her wounds.

“There is no moving Father,” Richard said dejectedly.

It pained Eleanor to speak, and the pain in her heart was greater still—Henry had raised his hand to her; she still could not believe it—but she forced herself to clarify things for her boys. “There is more to this than his obduracy,” she mumbled through her cut lip. “He cannot see or comprehend what is happening right under his nose. He sees his word as law and expects it to be obeyed.” She sighed, fighting back tears. She must remain strong, for no one else would champion her sons’ cause.

“You are aware that your father and I have lived apart for some time,” she said gently. “That was our mutual decision. We had had our differences, yet we remained friends and allies. Today, that has all changed, for I will not have my children cheated of their rights. Plainly, we are in one camp, and your father is in another. That makes us enemies, although it grieves me to say it. But I promise you now, all of you, including Young Henry, that I will fight for your rights, and I will make the King see sense!”

“Will there be a war?” Geoffrey asked eagerly. He was desperate to prove himself in battle. But Richard’s face remained grave; a year older, he had realized the true implications of the rift. Eleanor could guess what he was thinking—they were that close.

“Your father said that a kingdom divided would be brought to desolation,” she mused. “Well, he has this day divided his kingdom, and if it all ends in desolation, he must bear the responsibility. By his stubbornness, he has laid himself open to the thing he most dreads. But I will not let it happen; there is too much at stake, for he is putting this empire we have built at risk. I have always been a true, loyal wife and helpmeet to my lord, but I will not stand by and see my sons treated unjustly. He is wrong, utterly wrong, and we must make him face that.”

Then her voice turned wistful, less strident. “This saddens me more than I can say. There should not be discord between father and son, or husband and wife. It is against the natural order of things.”

“What wonder if we lack the natural affections of mankind?” Richard laughed humorlessly. “We are from the Devil, and must needs go back to the Devil!”

What could she do to force Henry to his senses? Dare she write to Louis? It had been so long. Yet something told her that he would welcome her intervention. There was no doubt he was of the same mind, although for different motives. She wanted justice for her sons, and for them to enjoy their right to a share of their father’s power; Louis wanted Henry’s empire disunited. He too had evidently read the Scriptures.

But what exactly did the Young King want? Was it sovereign authority, even if that meant the overthrow of his father? If so, then what she was contemplating was dangerous in the extreme. At its best it was rebellion—at its worst, treason.

She must talk to her oldest son as soon as she could and find out what was in his mind. If it were indeed Henry’s ruin, then she must try to talk some sense into the Young King. In the meantime—it could not hurt, surely—she would write to Louis, parent-to-parent, as it were, and confide to him her concerns. One word from him, threatening the peace that Henry had worked so hard to negotiate, might be all it would take …

And there was another thing. Louis was her overlord; she had every right to appeal to him for aid against her enemies. And, by his insupportable acts, Henry had now made himself her enemy. She herself had not created this terrible situation. She had been trying all along to find a peaceable solution.

Putting quill to parchment, she found her thoughts drifting hopefully back through the years to a young man with long yellow hair who had been so pathetically eager to please her …

45

45

Limoges, 1173

When Eleanor next saw Henry, he made no reference to what had passed between them; nor did he refer again to the rift with his sons. Yet he could not have failed to notice the frigidity of her manner toward him, or that she shrank from his touch. It seemed he no longer cared what she thought of him.

His striking her had changed everything. There was nothing unusual in a husband beating his wife, of course: it was a man’s right, and she knew of many women who had to endure such chastisement. She also knew of several churchmen who wanted to limit the length of the rod that was used, but they had been dismissed as eccentrics. No, the issue here was that, in lashing out and wounding her, Henry had brutally demonstrated that his respect for her, and his love and regard, had died—and he had let her sons see that.

And something had died in her too. She could no longer bear to be in his presence.

He had insisted on her traveling south with him to Limoges, where he was to host a week of lavish banquets and festivities in honor of the betrothal of the Lord John to Alice of Maurienne. The guests of honor were to be Alice’s father, Count Humbert, the Kings of Aragon and Navarre, and the Count of Toulouse. Richard was to be present, as Duke of Aquitaine, and Henry had summoned the Young King from Hautfort; Geoffrey he had sent back to Brittany. Divide and rule, Eleanor thought cynically.

And that was how the great baggage train of the Plantagenets came once more to be wending its cumbersome way south through the Angevin territories. It was February, and cold, when they left Chinon, but Limoges, when they arrived, was mild, and the town was en fête. Although her heart was frozen, Eleanor mentally girded her loins and donned her most sociable mask, conducting herself as charmingly and wittily as ever toward her august guests. She warmed to the flattery of the Spanish kings, and reveled in the blatant regard of the black-haired Count Raymond of Toulouse, with whom, many years earlier, she and Henry had once been at war, each claiming that Toulouse belonged to them. Although Raymond had won the day, it seemed that he cherished no hard feelings toward his former aggressor. She wickedly hoped that Henry had seen him flirting outrageously with her. At fifty-one, it was balm to her broken heart and scarred lips to luxuriate once more in a man’s frank interest.

“I had never believed the reports of your beauty until I met a man called Bernard de Ventadour,” Raymond told her as they sat at the high table, dining off gold plates and drinking from crystal goblets. “He was a troubadour—you may remember him.”

“I knew him. He was once at my court,” she told him.

“He loved you, truly. Your husband the King had dismissed him through jealousy, and he sought refuge at my court. He pined for you so greatly; did you know that?” Raymond’s startling blue eyes, set in an angular, handsome face, were searching.

“I knew he had a regard for me,” Eleanor said. “But, although I say it myself, all the troubadours claimed to be in love with me. I was the duchess, and it was more or less expected of them.”

“But Bernard was special,” Raymond insisted. “His songs were not mere flattery, but inspired by the heart. I judge him to have been one of the greatest poets of our age.”

“You speak of him as if he were dead.” Eleanor paused.

The count sighed and laid down his knife. “Alas, madame, he is. His grief was such that he sought refuge and peace in the abbey of Dalon in the Limousin, where he ended his days not long after.”

“I am sorry for that,” she said, feeling regret that she had so lightly dismissed Bernard’s devotion.

“You could say he died for love of you—and most men, having seen you, would understand why.”

Eleanor recovered herself and frowned at Raymond in mock reproof. “Do you know how old I am, my lord?”

“If you tell me, I will not believe it. Madame, you rank among the immortals, your fame and beauty are legendary, and I can see for myself that the reports do not lie!” This was accompanied by increasingly animated gestures, and Eleanor noted with secret glee that Henry was looking at them suspiciously, and toyed mischievously with the idea of taking Raymond to her bed, to spite her husband further. It would not be difficult to seduce the amorous count. Dare she do it? It might be all that she needed to quell her inner turmoil and pain.

The Young King arrived on the third day, shortly after a messenger from the court at Paris, who had brought letters of congratulation for the King and Count Humbert—and a secret missive for Eleanor.

Dragging herself away from her tower window, through which she had been hoping to espy her eldest son and his retinue approaching across the distant hills, she hurriedly broke the seal. It was from Louis, offering her and her sons his support against the unjust treatment of her husband. As Henry’s overlord, he said, he had the right to demand the righting of the wrongs that her lord had done his heirs, and he, Louis, would pursue that even to the point of resorting to arms.

Her hands were trembling. She was horribly aware that in invoking the King of France’s aid, she had committed treason against her lord. Louis’s response had forcibly brought that home to her. She had not meant Henry any harm, had wanted only to make him aware of the needs of their sons. But it was probably too late to retract now. The letter had been written, the damage done. She suspected that the Young King would have been in touch with his father-in-law and received a similar assurance anyway.

And here was the Young King now, his party just visible in the distance. His mother stilled her conscience and forced a smile. She had longed to see this oldest son of hers, yet realized that his presence here could only mean trouble. And that, with what she knew, and the heavy knowledge of what she had done, she would be involved in it up to her neck.

King Henry had gathered his family, his guests, and his court in the great hall of the Abbey of St. Martial for yet another celebratory feast, and it was here that, with his face set hard like granite, he received the Young King and Queen Marguerite. To make matters worse, the younger man exchanged the kiss of greeting with his father in sullen silence, having barely bent his head in obeisance. His embrace of his mother was far warmer.

His disrespect did not go unnoticed. The Kings of Aragon and Navarre exchanged disapproving glances, while Raymond of Toulouse raised his elegant eyebrows at Eleanor. But she would not acknowledge him, and took her place between the two Kings, her husband and her son, for the solemn banquet.

After the cloths had been drawn and spiced wine served, the company proceeded into the church for the betrothal of the Lord John to Alice of Maurienne. The future bride was an exquisite child of four with chestnut curls framing her sweet, round face; her father, the portly Count Humbert, looked quite distressed at the prospect of giving her away, for she was his only, cherished child. But soon the deed had been done, and she was affianced to the six-year-old John, who could not have looked less interested. John’s avid curiosity had been captivated by the wonderful luxury and excitement of this rare week away from his cloistered existence, and he saw his betrothal only as a means of escaping his frustratingly ordered world.

The ceremony over, the moment had come for Count Humbert formally to commit his daughter into the custody of the English King, and there were tears in his eyes as he lifted Alice up, kissed her, then set her down and gently pushed her into a wobbly curtsey. Henry patted her on the head.

“Queen Eleanor here shall care for her as if she were her own daughter,” he assured the anxious father, and Eleanor stepped forward and gathered the little girl up in her arms.

“As dowry, I give you the four castles stipulated in the marriage contract,” the count confirmed, “and I formally designate the Lord John my heir.” Henry glared at the fidgeting John, indicating with a sharp downward nod that he should bow in acknowledgment of his good fortune, which he belatedly did.

There followed a second ceremony, in which it had been decided that Count Raymond, now acknowledged by Henry and Eleanor as Count of Toulouse, was to pay homage to them as his overlords. But Henry had made a change of plan. He had the glowering Young King and Richard, as Duke of Aquitaine in place of Eleanor, stand beside him, and obliged the count to swear fealty to the three of them. That prompted outraged murmurs from Eleanor’s subjects: what business had the Young King to be involved? It was Richard’s right, alone of the sons of Eleanor, for had not King Louis recognized him as the overlord of Toulouse?

Eleanor too could not mask her fury. How dare Henry slight her, the sovereign Duchess of Aquitaine! But look at him! He was standing there beaming, happy to ride roughshod over everyone’s sensibilities—as usual! In her fury, her resolve hardened. It was not the Young King’s fault that he had been dragged into this; God knew, he had supportable grievances enough of his own. But that Richard, her Richard, had been obliged ignobly to compromise his lordship—that she could not forgive. Henry must be stopped. If she had to commit treason to do it, then so be it—she would do it.

She guessed that when the feasting came to an end and the guests had withdrawn, there would be a family bloodbath, and she was right. Before she and Henry could retire to their separate chambers—never again, she had vowed, would they share a bed—Richard had collared them in the stairwell and complained bitterly of the slight he had received.

“Your brother is my heir. Let that be an end to it,” Henry said dismissively.

“Yes, but not the heir to Aquitaine!” Richard stormed. “He has no jurisdiction in this territory, nor ever will.”

“Henry, you were unjust,” Eleanor added coldly.

“Cease your complaints!” Henry growled. “I’m going to bed.”

“Not so fast, Father!” It was the Young King, come up behind them. “I have something to say to you. Do you want me to say it here, or shall we do it in private?”

Henry turned on the stair and scowled down at him. “You had all better come to my solar, and we can get things straight, once and for all,” he said.

“Yes, we will,” his son promised, his eyes blazing with purpose.

Eleanor took her place in the carved chair by the brazier. Her two sons placed themselves firmly on either side of her, making it quite plain that they were all three allies. Henry stood facing them, feet planted firmly apart, arms folded across his chest, jutting his bull-like chin out defiantly.

“Well? Out with it!”

The Young King bristled. “Why do you refuse to delegate any power to me and my brothers?”

Henry’s eyes narrowed. “Because you are not yet ready for it, as your hot-headed behavior proves.”

“So John, at six, is ready to administer the castles you have given to him—castles that belong, by rights, to me! I had no wish to give them to him, and you had no right to dispose of them!”

“I have every right,” said Henry, abandoning his inquisitorial pose to pour himself some wine. “I am the King. Everything is mine to dispose of. And I’m not dead yet.”

“You may not dispose of your lands here without the consent of your overlord, the King of France,” the Young King said, smirking nastily, “and I must tell you that it is King Louis’s wish—and that of the barons of England and Normandy—that you at least share your power with me, and assign me an income sufficient to maintain my estate.”

Henry stared at his son. “You havebeen busy,” he snorted. “Tell me, does it behoove my son and heir to go behind my back, cozen my barons, and consort with my ancient enemy?”

“That which you reap, you must sow, Henry,” Eleanor told him. “There was no other way for him to receive justice, you must see that.”

“I’d give it another name, madame.” The King regarded her with contempt. “I’d call it treason.”

Her face must have betrayed her. Her sons looked alarmed as Henry bore down on her. “What do you know of this, Eleanor? Have you been stirring up trouble too?”

“I but support my own blood,” she answered evasively.

Henry thrust his head forward until they were face-to-face, noses almost touching. “But you would not go so far as to appeal to Louis for support, I hope!”

“I have no need to. It seems our Henry can take care of himself.”

Henry stood up, dissatisfied, yet not wanting to pursue the matter further for the moment. Surely she would not have gone so far!

“Out!” he commanded his sons. “And don’t come bothering me with your endless complaints and demands again. Go on, out! I wish to speak privately with your mother.”

Reluctantly, like naughty children, Young Henry and Richard left the room, their eyes smoldering, hatred burning in their breasts. Eleanor watched them go and grieved for them, but her attention was immediately demanded by Henry.

“If I find you have betrayed me,” he warned her, his voice deadly serious, “I will kill you.”

“That would not surprise me, after the violence you have shown me,” she retorted, keeping her nerve. “Henry, why have you come to hate me so? Is it because you can’t bear it when I’m right?”

“It’s because you have set yourself in opposition to me, when you should be supporting me,” he replied. “You never show me the proper meekness of a true wife.”

“I never did!” She laughed mirthlessly. “It didn’t bother you in the old days. You liked my spirit—you often told me so. But I now speak a truth you do not want to hear.”

“Just stop interfering. You’re a woman, and these are affairs for men.”

“Then why did you send me here to rule Aquitaine? Did you think me incapable of sound judgment back then? God’s teeth, Henry, I could run circles around you!”

“You think you have some fatal power over me, don’t you?” Her husband sneered, his features contorted in what looked like loathing. “Well, you don’t. You are an irritation, that’s all.”

“I am your wife and your queen!” Eleanor cried, incensed. “You were lucky to marry me, for I could have had my pick of the princes of Europe. But I have always done my duty by you. I have been a true wife these many years, and a helpmeet when you needed it. I have borne you sons—”

“Yes, God help me!” Henry flung back. “I wish I could get more and disown these ungrateful Devil’s spawn …”

“Then perhaps you should marry one of your whores, and do just that! Mayhap Rosamund de Clifford would oblige, or did you abandon her long ago, as you abandon most of the women you’ve fucked?”

It was the first time in six years that the name Rosamund had been uttered between them. For Eleanor, it had been a long shot, for she had heard nothing more of the girl since that terrible night when Henry admitted his love for her—and had, indeed, not wanted to hear of her. He had rarely been in England since then, so she supposed the affair died a natural death. But now she could see by his expression that she had been horribly wrong.

“I have never abandoned Rosamund,” he said, deliberately aiming to hurt her. “She is here, in Limoges. She traveled incognito, with a separate escort, and I have slept with her every night since I arrived. There—does that satisfy your curiosity? I told you, Eleanor: I love her. Nothing has changed. I do not love you. I prefer to hate you.”

“It’s the other side of the same coin,” she riposted, wondering why tears were threatening to spill down her face. “Tell me, Henry, do you hit her as you hit me? Does she please you in bed as much as I did?”

He looked at her darkly. “Rosamund would never give me cause to strike her. She is a gentle soul. And yes, she brings me much joy—more than you ever did! Look at yourself in the mirror, Eleanor, and ask yourself why I no longer lust after you. Look at the harridan you have become!”

He is doing this to bait me, she told herself. It is his way of being revenged for what he sees as a betrayal. I must not take it to heart—and anyway, what need have I to? I no longer love him, so why should I care? But she was honest enough to realize, to her dismay, that she did care—that she wanted to rake her nails down Rosamund’s alabaster cheeks and ruin her beauty, that she wanted to fling herself at Henry and beat the breath out of his chest for being so cruel—and so stupid!Instead, she rose to her feet with immense dignity, picked up a candle, and made to leave. But Henry stopped her, reaching out and taking hold—none too gently—of her arm.

“You and I are finished, but my sons are yet young,” he said. “By reason of their age, they are easily swayed by their emotions and misplaced loyalty. I am beginning to suspect that a certain red-haired fox has corrupted them with bad advice and stolen them away from me. Isn’t that so, Eleanor?” His grip tightened.

“You are a fool, Henry,” she told him with scorn. “You delude yourself. You are the cause of this tragedy.”

“No, I am not a fool, or deluded,” he insisted. “I can see clearly that my own wife has turned against me and told her sons to persecute me.”

“You are sick!” she cried, and twisting free, ran down the stairs.

She could not face going to bed. Instead, she found herself pacing up and down in those same cloisters where she had confided her concerns to Raoul de Faye. Within her, the tempest raged. They were destroying each other, she and Henry, and there was no help for them. Since Becket’s death he had changed, coarsened, become abrupt and unkind. He had betrayed her, abused her, and slighted her; he had said cruel, unforgivable things. She would not believe them, she must not …

“Eleanor?” A man slipped out of the shadows. It was Raymond of Toulouse, his face full of concern—and something else that she recognized as desire. “Forgive me for intruding, but you are troubled. Can I help?”

How long had he been there? Had he been waiting in the hope of waylaying her? He had been bold indeed to address her by her given name rather than her title. What could that betoken but amorous interest? And how had he guessed that nothing could have been more welcome to her wounded soul on this terrible night?

She went to him unspeaking, finding refuge in his arms, and sweet pleasure in his kiss. Afterward, having stolen furtively up with him to his chamber, she watched his eyes roving over her as she disrobed, then lay naked on his bed, and knew that she was not the aging harridan that Henry had so cruelly called her. Ah, it was bliss to feel her body come alive again after so long, to shiver under a man’s caress, and squeeze eager fingers around his virile member, surprising herself by the erotic response deep inside her. She could not be old if she felt like this, she told herself, as Raymond rolled and tumbled her on disarrayed sheets, riding her vigorously until she cried out in pleasure that was almost pain.

When it was over, and he had subsided, panting, beside her, she tried to tell herself that sex had been better with him than with Henry, but her self-delusion lacked conviction. Henry had been by far the more accomplished lover—she was honest enough to concede that. But what had most struck her had been the strangenessof it, the predominance of physicality and the lack of emotion. She was forced to admit to herself that there was nothing so erotic as the touch of a familiar, loved body, and the meeting of true minds.